Serjeant William Henry Johnson VC, public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.

On 11 November 1918, the bells of Worksop Priory – like many across the country – rang out to celebrate the Armistice. In Worksop they were particularly remembering several of their members who were serving in the armed forces, especially Serjeant William Henry Johnson, 1/5th Sherwood Foresters, wounded in early October and still in hospital at Trouville, France.

The bells rang out again on Sunday 15 December after the Vicar of Worksop announced at evensong that the previous day the London Gazette had included the award of the Victoria Cross to Johnson for actions on 3 October 1918. That evening they rang a quarter peal of 1,260 changes of Grandsire Triples (the first quarter peal for the 15-year-old R Wright), and the following day there was more generally celebratory ringing. The previous Sunday, Johnson had written to one of the ringers from hospital, thanking them for remembering him during the Armistice Day ringing and mentioning, ‘I have undergone another operation. […] I have not got out of bed yet, but hope to do so very shortly.’

Early years

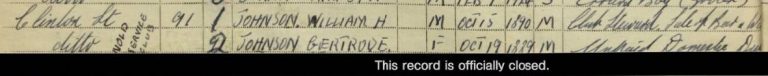

William Henry Johnson was born in Worksop on 15 October 1890. His parents, William Edward Johnson and (Harriet) Elizabeth Wing, had married in Worksop in late 1887. Their first child, (John) Edwin, was born in 1888. The family were living at 3, Court 4, Park Street, Worksop during the 1891 census. A sister, (Alice Annie) Mabel, and brother, Albert, were born in 1892 and 1894 respectively.

By 1901 the family were at 8, Court 8, Bridge Street, Worksop. In addition to the six family members there were two lodgers: William T Widdowson (30) and John Rawlinson (22), both working in local mines. In 1904, not long before Johnson turned 14, his father died. His father, grandfather and some of his uncles seem to have had a painting and decorating business, but Johnson followed the family’s lodgers down the mine. He worked at the nearby Manton Colliery.

On 2 August 1909, Johnson married Gertrude Walton. On 19 October 1909 their first child, Mabel, was born. In the 1911 census they were recorded living with Gertrude’s parents, John (67) and Mary (65), at 21 Prior Well Road, Worksop (now known as Priorswell Road). John was brewery labourer, while Johnson is listed as a coal miner’s filler. On 2 July 1911 Gertrude had their second child, William Albert.

In 1909 a man named Herbert Haigh had moved to Worksop, and set about reviving bell ringing in the area. He had grown up in Lincolnshire, and had travelled considerable distances – often on foot – in order to be able to learn more advanced ringing, as the ringers of his own tower were very set in their ways. This made him determined to bring on other ringers. It seems that one of those who initially joined the ringers in Worksop was Albert Johnson, uncle of William Henry Johnson.

It was presumably this connection that brought Johnson himself to ringing in 1913; a report after he was awarded the VC states that he had been ringing five years, and had rung quarter peals in five methods before he joined up. A quarter peal is a ringing performance that takes about 45 minutes of continuous ringing. Details of four quarter peals in 1914 have been traced, but two of those are in the same method, and none is marked as his first.

Army service

On 8 February 1915, Johnson travelled to Newark to enlist; only fragments of his service record survive due to the bombing of the Army Record Office during the Second World War. However, there is sufficient to understand the outline of his service, although some of the dates are difficult to read. He was medically examined on 8 February and passed fit. The following day he was formally attested as Private 3538, 8th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment). He was then posted to 2/8th Battalion in Luton for training. This was the ‘second-line’ unit, formed of those who had not volunteered for overseas service, and those undergoing training. Johnson fell into the second category, having signed the Imperial Service Obligation when he joined up. The battalion remained in Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire until 1916, with spells at Dunstable and Watford.

Soon after he arrived, the home defence men were hived off into the new 3/8th Battalion; the intention was that 2/8th Battalion would eventually proceed overseas as a unit, although they also continued to send replacement drafts to 1/8th Battalion as required. Unusually, the battalion war diary for this period survives (see WO 95/3025/8). The battalion was brigaded with the other Sherwood Foresters second line battalions as 2/1st Sherwood Foresters Brigade in 2nd North Midlands Division. These units were later designated 178 (2nd Notts and Derby) Infantry Brigade and 59th (2nd North Midlands) Division.

Around the end of August 1915 Johnson was given leave. While at home he managed to ring a quarter peal of Kent Treble Bob Major on Sunday 29 August. Perhaps this leave is also when Gertrude told him that she was expecting their third child: Gladys May was born on 9 February 1916.

In April 1916, the division was rushed to Ireland in the wake of the Easter Rising. There is no war diary for this period, so the part that Johnson played is not known precisely. He had been appointed lance corporal (unpaid) on 28 February 1916, and then lance corporal (unpaid) on 17 April, shortly before the battalion’s move to Ireland. In January 1918 the division returned to England, based at Fovant. Orders for France were soon received. Johnson was appointed lance serjeant on 1 February, so was presumably wearing serjeant’s stripes when King George V inspected the division on 13 February. The battalion crossed to Boulogne on 27 February 1917 and Johnson was promoted substantive corporal the same day (retaining the appointment of lance serjeant).

The front line

Despite GHQ expressing some doubts as to whether they were really fully trained as a division, due to the time spent in Ireland, they were soon in the front line. In April 1917 the Germans began a planned withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line and 59th Division were involved in the pursuit, which saw some heavy fighting. After a brief rest in early May they were soon back in the front line, but in June were pulled out of the line in order to begin preparing for the planned offensive around Ypres. The battalion war diary can be found in WO 95/3025/9.

They were not committed to the Third Battle of Ypres until September, initially consolidating gains made by 55th (West Lancashire) Division in the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge and then making their own attacks in the Battle of Polygon Wood. In October they were moved back to France, but still in the front line (despite suffering 2,000 casualties across the division during their brief time in the Ypres area). They were then warned that they would be taking part in the next big push around Cambrai, although again not in the initial assault. During the Battle of Cambrai the division took part in the Battle of Bourlon Wood, and then the defence against the German counterattacks.

The division rested for much of December 1917 and January 1918. Johnson was promoted substantive serjeant on 10 January 1918. The British Army was undergoing a major reorganisation at this time, and as a result 2/8th Battalion was to be disbanded. Johnson was posted to 2/5th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters, on 29 January (in the same brigade as 2/8th had been); their war diary is in WO 95/3025/2.

In March 1918, 178 Infantry Brigade was one of those that suffered extremely heavily when the the Germans launched their Spring Offensive, and were pulled out of the line and sent back to Ypres in early April. They had received a few reinforcements when the Germans launched a new attack, now in Belgium; again the brigade suffered very heavy casualties in this, the Battle of the Lys.

As a result, 2/5th Battalion was reduced to training cadre, and spent May instructing the garrison guard battalions that had been sent out from the UK to reconstitute the brigade. In June they began training the American 317th Infantry Regiment.

Johnson was transferred to 1/5th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters on 6 July 1918 (see WO 95/2695/1 for war diary). 1/5th were in 139 Infantry Brigade in 46th (North Midland) Division. July, August and the first three weeks of September were fairly quiet for the division, but now the tide of the war was turning following the Battle of Amiens, and the Germans were being forced back by the Allied Hundred Days Offensive.

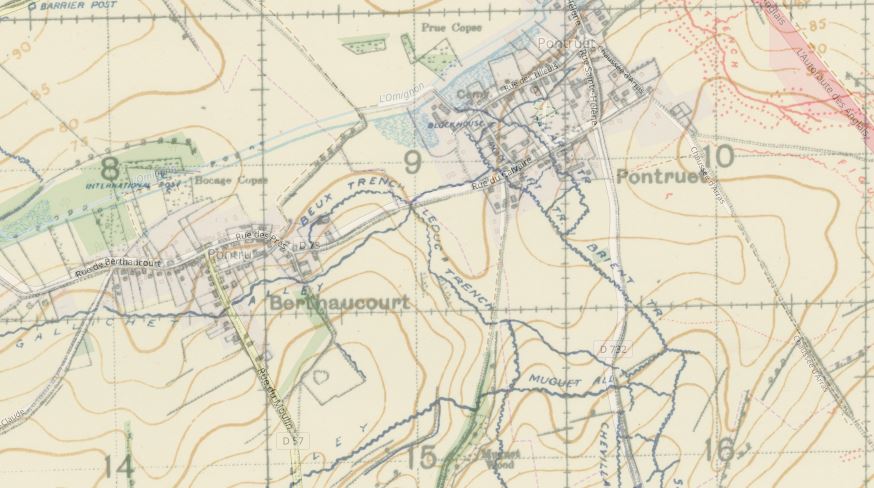

Trench map 62B.SW as at February 1918 from National Library of Scotland digitised collection, overlaid on modern OpenStreetMap imagery. This shows Pontruet and the Beux and Leduc trenches (between Berthaucourt and Pontruet) attacked by 1/5th Sherwood Foresters on 29 September 1918.

Johnson in action

46th Division were ordered to attack Pontruet on 24 September, with 1/5th Sherwood Foresters attacking Beux and Leduc trenches. Then, on 29 September came the attack which made the division’s name. They were ordered to cross the St Quentin Canal in the area around Bellenglise. This seemed an impossible task, as the canal ran through a deep cutting making a natural defensive line, and there were more defences behind. The division had been provided with life jackets and a range of pontoons and other devices for crossing the river, but men of 1/6th Staffordshire Regiment (in the leading 137 (Staffordshire) Infantry Brigade), with attached Royal Engineers, managed to seize Riqueval bridge and prevent the Germans blowing the prepared demolition charges. As a result, the other brigades were able to cross and continue to their objectives.

In the later fighting on the high ground west of Bellenglise, Lieutenant Colonel (the Reverend) Bernard Vann, commanding 1/6th Sherwood Foresters, showed inspiring leadership to keep the attack moving, for which he would be awarded the Victoria Cross. By 30 September the 1/5 Sherwood Foresters were billeted in the newly captured village of Lehaucourt (just north of the canal, between the dotted dark blue and light blue lines on the map below). All objectives were attained, and over 4,000 POWs, 40-50 guns and hundreds of German machine guns were taken.

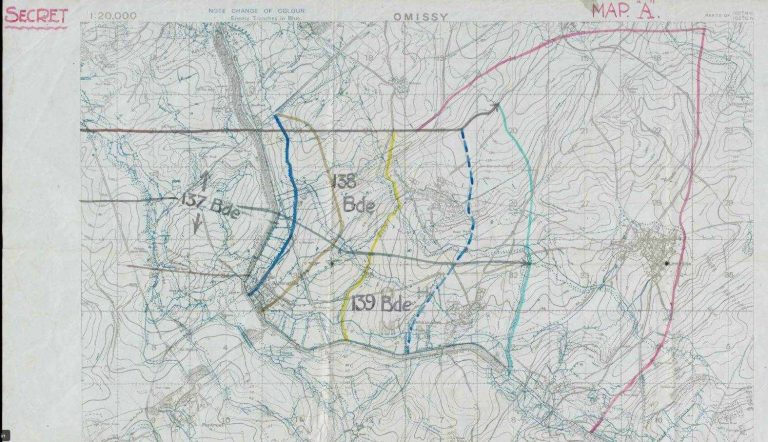

Extract from map in WO 95/2695/1 showing the attack made by 46 Division on 29 September 1918. Pontruet, which they attacked a few days earlier is in the bottom left of the image.

For the first couple of days of October the attack was taken up by 32nd Division, but on 3 October, it was 46th Division’s turn again, with 1/5th Sherwood Foresters to be the leading battalion in the attack on the villages of Ramicourt (top right on the map below), and Montbrehain (just off the map east-north-east of Ramicourt). The battalion formed up with its left flank anchored on the cross roads in map square 15 (just to the west of the boundary with map square 16), and their line ran roughly south east from there. They were in position by 05:15. They then moved off north east towards Ramicourt at zero hour, encountering some stiff resistance on the Fonsomme Line.

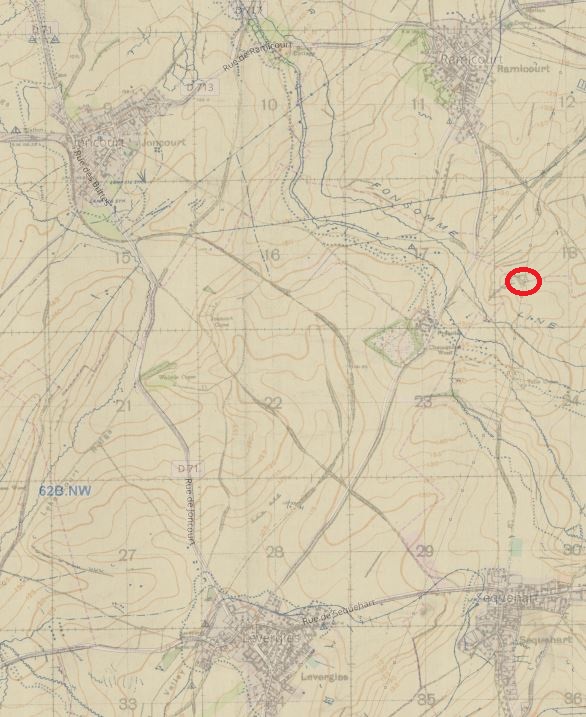

Trench map 62B.Nw as at 19 September 1918 from the NLS digitised collection, overlaid on modern OpenStreetMap imagery. The approximate location of Johnson’s VC action on 3 Oct0ber 1918 is circled in red. Levergies (bottom left of ths map) is also shown on the map above, just to the west of the pink line.

The after action report in the 139 Brigade war diary, WO 95/2693/4, and the citation for Johnson’s VC enable us to locate the action. Although the citation describes the action as near Ramicourt, the faint dotted pink lines from the modern map show that the location may actually lie just in the commune of Sequehart, being almost on the point where the boundaries of the communes of Levergies, Sequehart and Ramicourt meet. The citation was gazetted on 14 December:

For most conspicuous bravery at Ramicourt on the 3rd of October, 1918. When his platoon was held up by a nest of enemy machine guns at very close range, Sjt. Johnson worked his way forward under very heavy fire, and single-handed charged the post, bayoneting several gunners and capturing two machine guns. During this attack he was severely wounded by a bomb, but continued to lead forward his men. Shortly afterwards the line was once more held up by machine guns. Again he rushed forward and attacked the post singlehanded. With wonderful courage he bombed the garrison, put the guns out of action, and captured the teams. He showed throughout the most exceptional gallantry and devotion to duty.

The after action report indicates that, after passing through the Fonsomme Line, the battalion almost immediately came under machine gun fire from rifle pits just behind the main line of defence. The second post referred to in the citation is thought to be in a small copse on the higher ground (circled on the map above). The operation map in the brigade HQ war diary suggests that this area was actually slightly to the right of the intended operational area for 1/5th Sherwood Foresters.

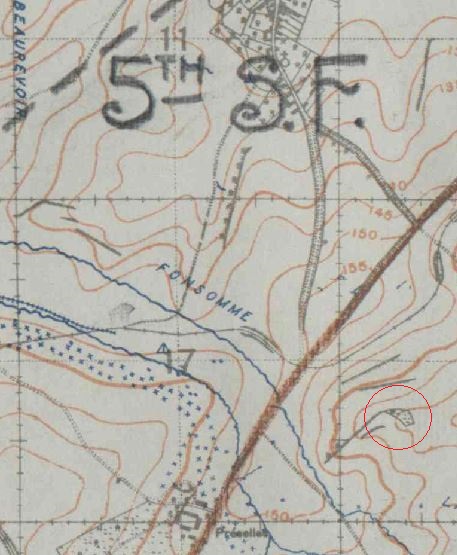

Map extract from WO 95/2693/4, 139 Infantry Brigade diary. The right hand side of 1/5th Sherwood Foresters is shown by the brown pencil line running diagonally through the map. The copse (circled) is outside this area.

As indicated in the citation, Johnson was badly wounded in the action, although his service record appears to date the wounds noted – ‘Gun shot wound, left shoulder and back’ – to 6 October. Johnson was taken to a base hospital in Trouville (four were based there at the time). He underwent at least two operations, and also contracted the Spanish flu.

Back in Britain

On 23 January 1919 he was transferred to 8th General Hospital in Birmingham. Following a medical board, it was determined that he should be discharged from the army due to his wounds. Without much notice, he was discharged from hospital on 11 February. Gertrude had been able to travel to Sheffield to meet him en route, and they made the journey back to Worksop together by train from there, arriving just after 17:00.

Despite the short notice, a large crowd had gathered. ‘Welcome home’ banners and other decorations adorned the streets, although there had not been time to arrange for a band to be present. The couple were met at the station by local councillors, some of the bellringers (including Johnson’s uncle) and representatives of other local groups, along with their children. Outside the station an open carriage waited, and the route back to Shelley Street was lined with people. Johnson seems to have been rather overwhelmed by this to start with, acknowledging the formal welcome speech with only a bow and salute. He had managed to gather his thoughts a little by the time the coach reached Shelley Street and gave a short speech, thanking everyone for their welcome, and saying:

[He had] noticed in the crowd a number of discharged sailors and wounded soldiers, and he would like to say this: that there was not one among those men who would not have done what he had done if they had been placed in a similar position on the battlefield; they would all, like British soldiers, have done their duty.

Later the Priory bells were rung, and Johnson went to speak to them in the ringing chamber, saying that he hoped to be back ringing with them the following Sunday.

On 28 March Johnson and his wife travelled to London ready for the presentation of his Victoria Cross by the King at Buckingham Palace the following day. When they returned to Worksop on the evening of 29 March there was again a large crowd waiting, and this time there was a band, which played Handel’s ‘Lo, see the conquering hero comes’ as the train drew in.

Over the next few months there were several presentations from local groups, his colleagues at Manton Colliery, various ringing associations, the church congregation, and so on. For many years he was treated as an honoured guest at ringing meetings. As late as 1930 he attended a dinner of the Sherwood Youths ringers in Nottingham, and when he was introduced the master of ceremonies invited all those present who had been in the armed forces during the war to stand, and everyone at the dinner toasted him. He also laid one of four foundation stones for the war memorial extension to the town’s hospital in 1923 as representative of ex-servicemen.

However, his wounds meant that he wasn’t able to work underground again. Initially he received a war pension (with an automatic 6d a day extra due to his status as a VC holder). He was able to keep ringing, though, ringing his first peal on 13 December 1919. This had been intended to take place on 28 June as part of the Peace Day celebrations linked to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, but two ringers were indisposed, Johnson possibly being one of them. He rang a few more peals, and was a slightly more regular ringer of quarter peals. The last I’ve traced was rung at St Paul’s Daybrook, Nottingham, on 30 May 1943.

He became the landlord of the Mason’s Arms, Worksop for several years, and was also involved with the lcoal scout troop and cadet unit. The family moved briefly to Retford around 1926, and then to Arnold, Nottingham. Here Johnson initially worked for a local brewery before taking on the Arnold ex-Servicemen’s Club. The birth of a third daughter, (Victoria) Jean, in 1929 may have come as a bit of a surprise, 20 years after the birth of their first child. They were still at the club in 1939, as shown by the 1939 Register:

Johnson initially served in the Home Guard, but had to resign for health reasons. This may explain why the family left the club in 1941 when he took up new employment with the Churchman cigarettes department of JP Player and Sons. By the time of his death, the family were living at 33 Nelson Street, Arnold. Johnson had apparently been very worried about his son, William Albert, who was injured in an accident while he was serving in a searchlight unit, leading to the amputation of one leg and the foot from the other leg. Johnson sat down for breakfast at home on 25 April 1945, and suffered a seizure. His death was reported in the local and national press. The funeral at Redhill Cemetery, Nottingham, on Saturday 28 April was with full military honours. The bearers were six sergeants of the Sherwood Foresters, and buglers played the Last Post. A course of Grandsire Triples was rung over the grave on handbells by some of the Daybrook ringers, and this was followed by a halfmuffled quarter peal on the following Monday.

Alongside this blog post I’ve been building up Johnson’s profile on ‘Lives of the First World War’, the permanent digital memorial for those who served. Details of sources used in this post can be found as evidence attached to the profile.

Bellringing

Today a VC memorial stone is being laid in Worksop, close to the war memorial, and there will be peal attempts at both the Priory at 10:00, and St Anne’s (which only received bells in 1977) at 15:30, and at other locations around the country. The peal at Worksop Priory will be in a new method called Ramicourt Alliance Major, named for the location of Johnson’s VC action. An exhibition featuring all six of Nottinghamshire’s First World VC recipients will be in Worksop until 10 October, when it will move on to other locations in the county.

Bellringing will also be an important feature of the centenary commemorations for the Armistice this year. The Department for Digital, Media, Culture and Sport has requested that bells are rung halfmuffled as normal for 11:00 services, but then the bells should be rung open around 12:30 to reflect the joyful nature of the original Armistice Day, as reflected by the ringing at Worksop described in the opening of this post. Ringing is also requested for the ‘Battle’s Over’ event in the evening. Alongside this has been the Ringing Remembers campaign, supported by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, and adminstered by the Central Council for Church Bell Ringers and the Big Ideas Company. This has aimed to recruit 1,400 new ringers to ensure that the bells can be rung at as many towers as possible, and symbolically ‘replacing’ the 1,400 ringers known to have died as a result of the First World War. I understand that this target has been well and truly beaten, but more new recruits are still welcome.

Last year, a new ring of bells was installed in the Anglican St George’s Memorial Church in Ypres. The Mercian Regiment (successors to the Sherwood Foresters) presented a set of replica medals and cap badge, which now hang in the ringing chamber there to remember Johnson’s service.

- Replica VC presented by the Mercian Regiment for the ringing chamber at St George’s Memorial Church Ypres. Image courtesy of and © Alan Regin.

- Sherwood Foresters cap badge, presented by the Mercian Regiment for the ringing chamber at St George’s Memorial Church, Ypres. Image courtesy of and © Alan Regin.

[…] of events in Worksop today including peal attempts at the Priory and St Anne’s. I’ve also written a blog post about him for The National Archives’ blog (with a bit of a plug for Ringing Remembers at the end and starting with Worksop’s original […]

Ringing associated with the centenary will be listed at https://bb.ringingworld.co.uk/event.php?id=8760

[…] A more detailed account of Sergeant Johnson’s life and service career has been provided by David Underdown on the blog of the National Archives: https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/tommys-war-w-h-johnson-bellringer-vc/ […]

William Henry Johnsons Granddaughter Margaret learnt to ring at Worksop Priory at the same time as myself and became quite an accomplished ringer, ringing her first peal at Cuckney with Herbert Rooke and the Warsop Band. Later on I believe she went to work for the Ordnance Survey as a Cartographer I believe in the Southampton area.

Thanks David. Quite a few family memebrs were present for the ceremony last week, there are now some photos on his profile on Lives of the First World War (link in original post).

Does the story of William Henry Johnson appear in any books? Ive been told there is one but my search has not revealed anything.

For the centenary commemorations local historian Robert Ilett produced a booklet of about 30 pages “Sergeant William Henry Johnson VC: A man of moral courage and modesty” which was published by Bassetlaw District Council, this had quite a lot of photos from the family and local collections. I don’t know how generally available this now is, I’d suggest contacting Worksop Library, or I was sent a copy by the Chesterfield Branch of the Western Front Association. The VC action at least is also included in the divisional history “Breaking the Hindenburg Line-the story of the North Midland Division” by Major Raymond E Priestley MC, and there will be something about him in the various volumes on First World War VCs. After completing this post I did find more details about his time in Nottingham in digitised newspapers, this information is included in the profile on Lives of the First World War, which has also had images of the centenary comemmoration in Worksop added.