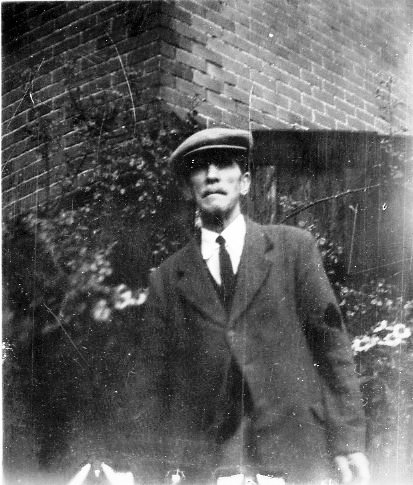

Gunner Albert Tarrant, RHA. The chevrons on his left sleeve are long service and good conduct stripes and indicate that Albert Tarrant had served in the Army for 18 continuous years

My First World War soldier is my great-great uncle. Although he is not a blood relation, he came to have a big impact on my family and is remembered with great fondness by my father. Albert Ernest Tarrant married my great-great aunt Elizabeth Anstey in Southampton 1916. In 1915 my grandmother was orphaned at the age of 8 – her father died in 1912 as a result of the sinking of Titanic and her mother in 1915 of tuberculosis, shortly after the death of her sister from diphtheria. She was taken in by her Aunt Elizabeth and Uncle Albert, who lived at 5 School Road, Totton, a suburb of Southampton.

Albert Tarrant was born in 1878. In 1898 he enlisted in the army and saw action in the Second Boer War (1899-1902) as a Gunner in the 8th Battery, Royal Field Artillery. Albert was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal with clasps for Cape Colony and Orange Free State. He remained in the army, keeping his number 28281 but transferred to ‘A’ Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, and was posted to India. ‘A’ Battery, known as The Chestnut Troop, was the senior battery within the whole of the Royal Regiment of Artillery.

At the outbreak of the First World War they were stationed in Ambala, India and left Bombay on 16th October on the SS Itria, arriving in Marseilles on 10 November 1914. On 8th December, with 170 men and 120 horses they travelled by train and saw action for the first time on 20th December at Givenchy, before replacing a section of 73rd battery at Pont Fixe on 23rd December.

The Chestnut Troop took part in the Battle of Neuve Chappelle during March to April 1915. Albert was in a detachment that saw action at the Second Battle of Ypres during April to May 1915 when he was temporarily blinded by chlorine gas, and was sent to Netley Hospital, near Southampton, to recuperate. Back in the UK, until his discharge, we believe that Albert was involved in training remounts to replace the large number of horses that were killed and wounded in the course of the war.

Albert was discharged as sick on 3rd May 1918 and was awarded the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, the 1914 Star, the Silver War Badge and the Good Conduct Medal.

I have been able to build up a picture of Albert Tarrant’s service from family stories and from medal rolls and unit war diaries. Unfortunately, like many other First World War soldiers, Albert Tarrant’s service records do not survive and even his attestation papers for the Boer War have been lost, as they were put together with his later papers. In September 1940, as the result of a fire caused by an incendiary bomb at the War Office Record Store in Arnside Street, London, approximately two thirds of 6.5 million soldiers’ documents for the First World War were destroyed.

War Diary for 'A' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, 'The Chestnut Troop', 23 December 1914. Image reference WO 95/1776/5

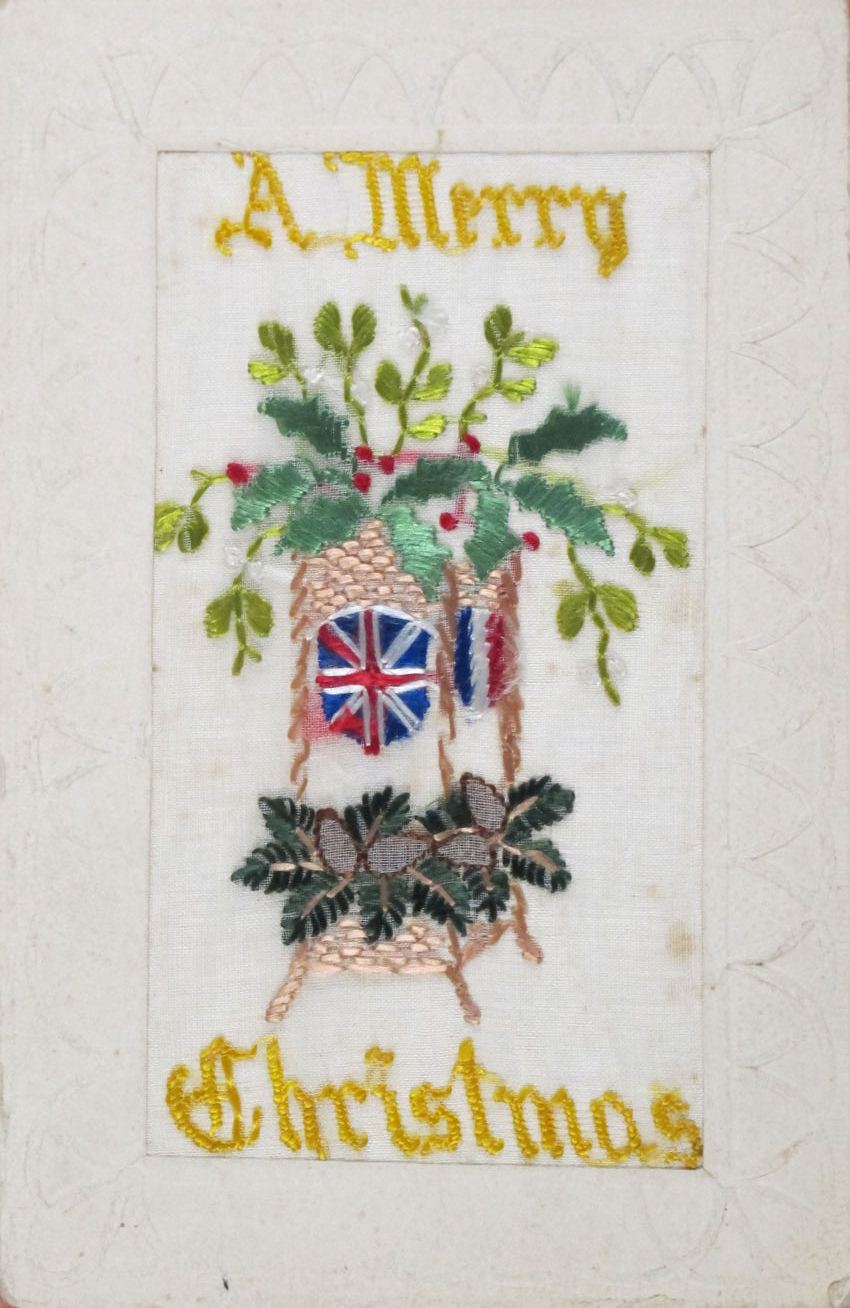

However, I am in possession of four silk postcards that Albert sent back from the front. Better known to military dealers as silks, it was once thought that these cards were hand embroidered by enterprising French and Flemish women who sold them to soldiers at or near the front. It is now considered that most of these cards were machine embroidered in factories in France and Switzerland, although some may have been hand-finished. The cards were very popular and it is estimated that some ten million cards were produced, establishing an enterprising war-time industry. The cards, while inexpensive to our 21st century minds, did represent a considerable sacrifice on behalf of the soldier, although estimates vary wildly as to their price, ranging from half to three times the daily pay of a private or gunner. Sadly, many of the soldiers who sent the cards never returned from the front.

The cards were clearly designed to be sent in an envelope or pouch through the military postal system, as they hold no address or stamp or postal marks. The four cards that Albert sent back are rather fetching in their embossed frames, and the colours of the embroidered silk threads remains vibrant and luminescent. On the back of each card Albert has pencilled a brief message dedicated to his loved ones, but giving no indication of what the soldiers were actually facing at the front. I’m sure that he was trying to shelter his loved ones from the horrors and misery of war, but also the soldiers were under a strict directive to avoid creating panic at home, and their post probably would have been censored, so there is no indication of casualties or hardship.

Instead these four cards are fairly indicative of the common themes that a collector would easily notice:  Remembrance. This is a beautiful card, with a gold extended fan, with the word ‘remember’ in silver lettering, around which are enlaced forget-me-nots and the flags of Serbia, Belgium, Great Britain, France, Russia and Italy.

Remembrance. This is a beautiful card, with a gold extended fan, with the word ‘remember’ in silver lettering, around which are enlaced forget-me-nots and the flags of Serbia, Belgium, Great Britain, France, Russia and Italy.

Patriotism, unity, perseverance and fortitude. This card is my favourite. Around a circular union flag in a green and gold border, beneath the royal crown, are the flags of Japan, Serbia, Russia, France, Belgium and Italy, on gold tipped poles, with the words ‘Until The End’ in gold lettering at the sides.

Patriotism, unity, perseverance and fortitude. This card is my favourite. Around a circular union flag in a green and gold border, beneath the royal crown, are the flags of Japan, Serbia, Russia, France, Belgium and Italy, on gold tipped poles, with the words ‘Until The End’ in gold lettering at the sides.

Festive greeting. Between the words ‘A Merry Christmas’, in a very jaunty gothic style script is a wicker two-tiered jardinière, with the flags of France and Great Britain on the sides, holly and red berries and mistletoe on the top tier and fir cones and ferns on the bottom. I particularly like the basket-work effect and the use of three types of green. The whole thing really stands out at you, simulating a 3 dimensional effect with great aplomb.

Regimental crests and insignia. A heavy gun in silver thread, with raised stitching to further define barrel, wheels, sights and breach, lies underneath a semi-circle of gun-smoke in a green field, with the letters RFA (Royal Field Artillery) beneath it in overlapping gold and black stitching, beneath which lie shamrocks and clover.

After the war, Albert Tarrant was employed for many years as a postman around the Southampton area. His Post Office personnel file is held at the Royal Mail Archive.

Albert lived on into the 1950’s and although his eyesight returned he was left with a hacking cough. In common with many servicemen returning from the front, Albert never spoke very much about his experiences and the horrors that he had witnessed, but he did regale his nephews, my father and uncle, with tales of how he had been ‘gassed at Wypers’.

Albert survived long enough to see my father join the Royal Artillery as a Second Lieutenant for his National Service in 1959. By this stage he was in his 80s and in a care home. When my father went to visit him in his uniform a smile lit up Albert’s face and he declared that he was very proud.

Beautiful precious ‘silks’ – so pleased that you have shared them. A beautiful and informative story well told about a brave man.

Hello Margaret I am rather late to this blog, but I stumble across an article by you in 2012 about your Grandfather from the 12th Lancers, Thomas Bell, Corporal 906 who was kia 20th November 1914. He is my Great Uncle and I have a great deal of information on his parents and 7 brothers and sisters, but little information on Thomas Bell himself. I would love to make contact with you and hope you can help. Thank you, Jan Somers from Brisbane Australia, grand daughter of Gertrude Bell, Thomas Bell’s sister who migrated to Australia in 1910.

Hello Margaret

I’m not sure if you will read this or not, as i posted earlier in response to your earlier comments about Tommy’s War and the Eastend of London. Thomas Bell , 906 of the 12th Lancers, is my Great Uncle. I have extensively researched the 8 Bell Children, of which Thomas Bell was the youngest, and Gertrude Bell, his sister was my Grandmother. – all 8 children were born in Highgate London to Elizabeth and Henry Bell. 5 of the Bell children migrated to Australia with their mother in abt 1910, including Thomas who returned to rejoin the 12th Lancers. Annie died aged 6, Henry Bell went to the USA and Ralph Bell went to the USA before going to Canada and joined the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Forces in France. Ralph was wounded, later dying in 1925 in Southampton of his infected wounds but on one of his hospital stays at Whalley in the UK, he visited someone at 3 Napier Street Norwich in about 1919, and I spent a long time researching who he might have visited but I now believe it might have been your Grandmother, Thomas Bell’s wife, and son after reading your blog posts.

I’d love to hear from you but don’t know how to get in touch as we never knew that Thomas Bell had any children. Hoping to find out more about Thomas Bell, and if I am on the right track, you and I are second cousins.

38 Pendle Close

Lambton

I am an ex gunner, loved the story and cards

Thank you for sharing this moving story and the impressive silk postcards. I can imagine how much they would have meant to Albert’s family.