The story of Private Hugh McIver VC MM and Bar

I have been privileged enough to have been afforded the opportunity to research aspects of the First World War in a variety of professional roles. That I have been able to do so is significantly linked to the story of my Tommy, as since I was a little boy growing up in a military family, I have been familiar with the life story of my relative Private Hugh McIver VC MM & Bar and his status as a local legend in the part of Lanarkshire my family comes from. This awareness, stemming from the pride my family has in Hugh’s standing as a Scottish war hero, inspired my initial interest in history as a child, my further study of the subject at university and is a fantastic frame of personal reference in my career as a researcher. Of course, I am biased, but I truly believe that the story of Hugh McIver’s life and death in action is a particularly extraordinary tale even when contextualised against the millions of extraordinary tales that make up the history of the British Army during the First World War.

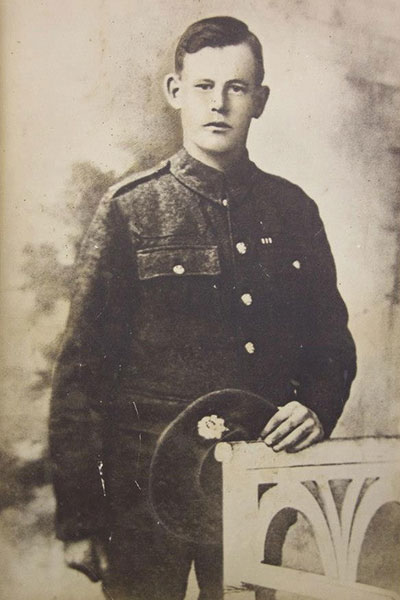

The account of Hugh’s life, and his service in the Royal Scots during the War, is even more compelling when we start at his humble beginnings and acknowledge that despite being gazetted for three gallantry medals between September 1916 and November 1918 (including the posthumous award of the Victoria Cross – Britain’s highest military award ‘For Valour’), my Tommy was far from a ‘model’ soldier and was in fact a strong-minded young Scotsman who was no angel. This story will be told in two blog posts due to my family’s luck regarding the wealth of surviving material relating to the life and service of Private McIver. Indeed he personally appears in records from most major series held at The National Archives and other institutions relating to the service of other ranks during the First World War. By journeying through them we can acknowledge the breadth of records available that teach us about army service during the War whilst learning about a scrappy wee miner who truly lived up to the motto of the Royal Scots: Nemo Me Impune Lacessit, roughly translated into Scots as ‘Wha Daur Meddle Wi’ Me?’ Hugh was born on 21 July 1890 in Linwood, Renfrewshire to Hugh and Mary McIver a Scottish Roman Catholic couple who were descended from Irish immigrants. Another Irish immigrant, my great-grandfather James Farrell of Newbliss, Co Monaghan, would marry Hugh’s younger sister Kate on 9 April 1920 in Cambuslang, Lanarkshire, making Private Hugh McIver VC MM and Bar my great-great uncle.

As family historians or researchers interested in exploring the lives of British soldiers it is important to remember that the above information, which I obtained using the Scottish Statutory Birth and Marriage Registers, is not available using the resources of The National Archives. The birth, marriage and death records for Scottish people are held by the National Records of Scotland, an organisation born out of the merger between the National Archives of Scotland and the General Register Office of Scotland. The public are able to review and order entries in the statutory birth, marriage and death registers from 1855-2013 online (these registers are equivalents of English and Welsh birth, marriage and death certificates) using a resource called ScotlandsPeople.

Using the Scottish census records from 1891, 1901 and 1911, also held by the National Records of Scotland and available on ScotlandsPeople, we learn that Hugh was the second oldest of Hugh and Mary McIver’s seven surviving children, and like his father before him Hugh would become a coal miner. The census records, and his sister Mary’s birth register, indicate that the family are already living at 34 Dunlop Street in Newton, Lanarkshire by 1894. And despite his birth in Linwood it is fair to consider Hugh’s ‘hometown’ as Newton, Lanarkshire, part of the parish of Cambuslang, as he spent the majority of his life living and working in Newton.

It almost goes without saying that life in Scotland for a coal miner from a large family was one that was inevitably hard, dangerous and not a little monotonous. With this in mind we can only speculate whether it was out of a sense of adventure or a sense of patriotic duty that 23 year old Hugh McIver joined the special reserve of the Highland Light Infantry (HLI) on 26 March 1914, less than five months before the outbreak of the First World War, pledging to remain in the reserve for six years’ service. This information is available using WO 364, or the ‘unburnt’ First World War service documents available to view online as the British Army ‘Pension Records’ on Ancestry.co.uk. When I first started to research the life of Hugh I remember being quite surprised to see a record for Hugh McIver appear in this series as a member of the Highland Light Infantry. The Hugh McIver of my granny’s stories was a member of the Royal Scots who died in 1918. Why would he have documentation relating to his discharge from the HLI?

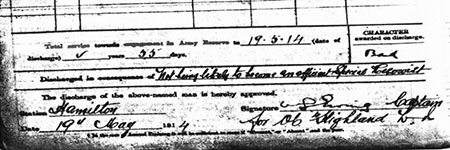

The answer, or part of it, lay inside the document itself. Having attested into the reserve of the HLI the Scottish war hero of my childhood was discharged 55 days later on 19 May 1914. Of great interest is the section of the document that notes the character he was awarded on discharge. Private McIver’s character is stated quite simply as ‘BAD’. He was formally discharged as he was deemed ‘not likely to become an efficient Special Reservist’. To those of us who know how this story ends, it is impossible not to possess a wry smile as we think of the decorated soldier Hugh would so soon become. The rest of the record is understandably brief; however WO 364 helps add further character, colour and understanding to Hugh McIver the man who would yet become a soldier.

From the point of view of a researcher, or a family historian, interested in the personal stories of the First World War, the destruction during the Blitz in 1940 of so many First World War service records will always remain a cause of great sadness. How many amazing stories have been lost due to the damage and destruction of so many of these records? It is due to this that my family must acknowledge our luck that Private Hugh McIver (12311) of the Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment) has a surviving service record in WO 363. The records of service for other ranks during the First World War (that like WO 364) are digitised and available to view online using the Ancestry website. The record confirms that Hugh enlisted on 18 August 1914, however despite Newton most certainly falling in the Greater Glasgow area, rather than joining a Glasgow regiment (such as the Highland Light Infantry) Hugh travelled east to Glencorse Barracks and enlisted in the Royal Scots, the oldest infantry regiment of the line in the British Army. Of interest is a section on the front of the attestation papers where Hugh is asked if he had ever served in the various bodies that comprise the British military and her reserve, the document intriguingly states ‘Yes, H[ighland] L[ight] I[nfantry] discharged on conviction’. The exact nature of this ‘conviction’ is not revealed, yet we can speculate that Hugh’s decision to venture east to join Kitchener’s Army may have been linked to his brief time in the HLI ending with some ignominy.

I have always found that one of the most helpful aspects of a service record is the ‘Statement of the Services’ coupled with the ‘Military History Sheet’. These sections of British Army service records help a researcher place where a soldier was, when and with whom. Hugh’s service record notes that his first posting was into 12th Battalion of the Royal Scots on 18 August 1914 and following service at home from 18 August 1914 to 10 May 1915, he was first posted abroad as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on 11 May 1915. Hugh would serve two years and 162 days in the BEF before being sent back home between 20 October 1917 and 11 February 1918. Fatefully, Private McIver would return to service abroad with 2nd Battalion Royal Scots from the 12 February 1918 until his death in action on 2 September that year. It can be seen therefore, using the evidence contained in WO 363, that Private McIver saw a significant portion of service abroad during the First World War, indeed he was a serving Private in the British Army from August 1914 until just two months prior to the Armistice with Germany.

Before his disembarkation in the ‘France’ theatre of war on 11 May 1915, Hugh was on service at ‘Home’, where according to his Service Record, he did not take to soldiery with the resolute calm professionalism you might expect of a man who become so decorated for gallantry by the end of the war. Private McIver’s service record states that on 20 October 1914 he was cited at Aldershot and confined to barracks for seven days for ‘making an improper reply to a Non-commissioned Officer’. Two months later Private McIver was deprived of seven days’ pay for being absent from tattoo until 10:30pm the following day. I believe that these citations for bad behaviour, and his discharge from the HLI, help create the image of Hugh as a man who knew his own mind, was not particularly fearful of authority and was in essence the embodiment of the hard and steely Lanarkshire pit-worker I wanted him to be. Private McIver’s ‘Admissions to Hospital’ form in his service record confirmed that whilst in France with 12th Battalion he suffered shrapnel wounds to his leg/buttock on 12 October 1917 and was sent back to Britain to recover.

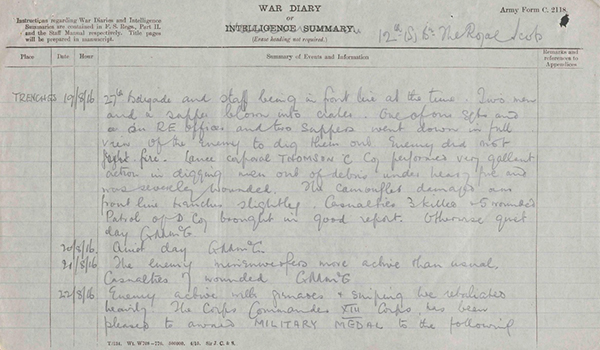

By this point, the 5ft 4½ inch 9½ stone Private McIver had spent over two years on the Western Front and had been wounded having previously received treatment for myalgia and rheumatism. He had also appeared in the London Gazette on 21 September 1916 (issues of the Gazette are fully searchable and online) to note the award of his first Military Medal, the second highest award for bravery in the ranks. Unfortunately, there is no exact citation for this medal but we can use the 12th Battalion Royal Scots War diary for the period, held by The National Archives in the WO 95 series (WO 95/1773/2), to ascertain what was happening at the time Private McIver was cited and rewarded for his bravery. On the 22 August 1916, the War Diary for the 12th Battalion Royal Scots stated the following: ‘The Corps Commander…has been pleased to award [a] Military Medal to the following…No 12311 Private H McIver…for conspicuous gallantry during operations at the Somme’.

The above use of records held by the National Records of Scotland, the Gazette and The National Archives allow us to understand Hugh as a brave man who was prone to spells of disobedience and who had no special talent for avoiding injury or trouble. Yet, it is following his recovery from his shrapnel wound and his posting back to France on 12 February 1918, with the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots, that My Tommy’s story, Private Hugh McIver’s story becomes more extraordinary.

I will post a follow up blog next month, using further records from the collections of The National Archives and other institutions, to resolve how a poor family from Newton pit ended up travelling to Buckingham Palace, as a result of my great-great uncle’s war service.

I always find a personal story really brings the first world war to life, as the real history of the war is about the endless amounts of lives it changed. Bloody good read and good to see he was only a little guy like me!

Truely humbling to read this blog and hear of this mans exploits, cannot wait for the next installment

Can I point out that Scotland’s People has restrictions on birth death and marriage certificates online for 100, 75. and 50 years respectively but you can visit Edinburgh pay a fee and view them.

I found your writings very real and could picture ‘your Tommy’

I am a novice at family history research but look forward to the say when I become such a good researcher as you so obviously have and I look forward to reading part 2.

To read this fascinating story of the hero Mr H. McIver is marvellous. Mr J. Fleming researcher, delving into his family hero history is remarkable and delivering such interesting reading is poignant. Really looking forward to the next episode. As a patron of the same parish I can say there is a STREET named after Mr McIver. So interesting to have such wonderful information about the man.

I have always been led to believe that my great great grandfather came to central Scotland from the Highlands, and whilst working in the “pits”, met and married a redheaded Irish girl called Mary Flynn. Although, Hugh senior, was Killed in a mining accident at Newton’s Old Pit his widow is buried in Cambuslang Cemetry, Where you can also see a memorial headstone to her son “The VC”. Hugh the VC, was one of 7 children, 1brother (my grandfather) who i’m called after, and 5 sisters, one of whom is the author’s grandmother.

I went to St brides cambuslang lstayed in King s cres lwent to school with Jack mcivor he told me his gra ndad

Was a VC l thoghht he was jocking well this was him

I

He was my grandmothers brother, I know something about his life now that i would never have known if i had not bfound this blog, thank you James Fleming.

That is an amazing story and he was very brave to earn all of those medals. Good luck with your blog. My mum is proud. Love aunt Michelle, Siobhan, Erin, Liam and niamh.

I’m currently doing family history research and of course know about my Great-Gran’s (Kate McIver) brother Hugh McIver, in fact my Gran (Agnes Bell, nee Farrell) went to the ceremony in France some years ago. This is a fascinating to learn about what an outspoken young man he seemed to be!

You have written that story so well I feel like I’m back in my grans living room sitting listening to her all over again , my gran was Hughes sister Jane mciver, she had many a stories to tell us about him , we are all very proud of him can’t wait for part 2

I’m knew Jack .mcivor

I was his grandad he was from kings cres sorryhis grandad was Hugh vc

Hugh mciver v.c m.m.bar was the brother of my grandmother maggie..didnt get to meet my gran.she had passed away before i was born..my mum theresa(loughrie) mckend would tell me the stories that my gran had about her brother hugh.

Hugh was some man and i would like to thankyou james fleming for the research you have done on our great uncle hugh..

Its a part of our family history alot of us wouldnt have known about..

What a great article. Thank you from another distant cousin 🙂

I am the great granddaughter of Jane McIver, Hugh’s youngest sister. My dad told me all about great uncle Hugh when I was a kid. He was so proud.

My grandmother was jane Mcguinness nee Mciver id like ro thank james for getting so much detail on my great uncle Hugh I’ve always been so proud of his story and his medals are back in the regiment museum at Edinburgh Castle