When I first sat down to write this, it began as the story of one man serving his country but as I began to recheck my facts, I realised that for one woman, this was actually the story of her family. Her husband. Her brother. Her brother in law. It must have changed her world irreparably, since only one of those men came back. And she won’t have been the only woman in this situation. We often talk about the losses of the First World War, but we don’t talk much about those who were left behind.

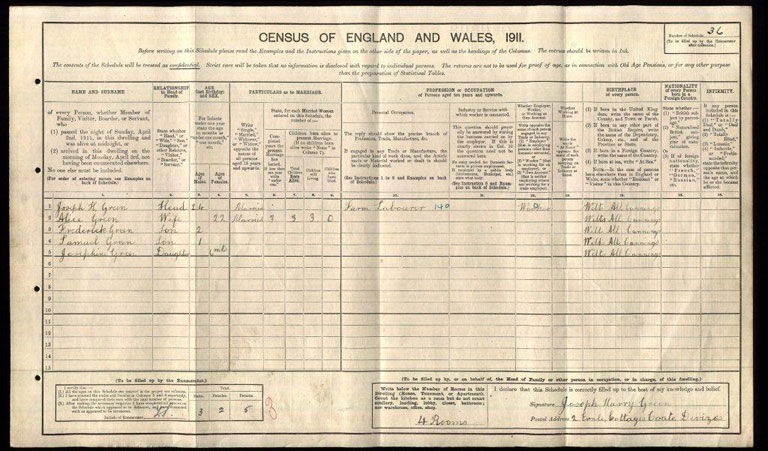

Let me start when I intended to begin. Pte. Joseph Harry Green (no. 19165) was born on 10 December 1886, the seventh child of twelve of John Green and Susanna Telley. As many of All Cannings were, Joseph was a farm labourer and is recorded as such in the 1901 and 1911 censuses, although by 1911 he’s living in Bishop’s Cannings, a village just over from where he was born. In 1907 Joseph married Alice Louisa Woodroffe, a local girl, and as the census shows by 1911 they had three small children. It is therefore Alice, really, around whom this post revolves.

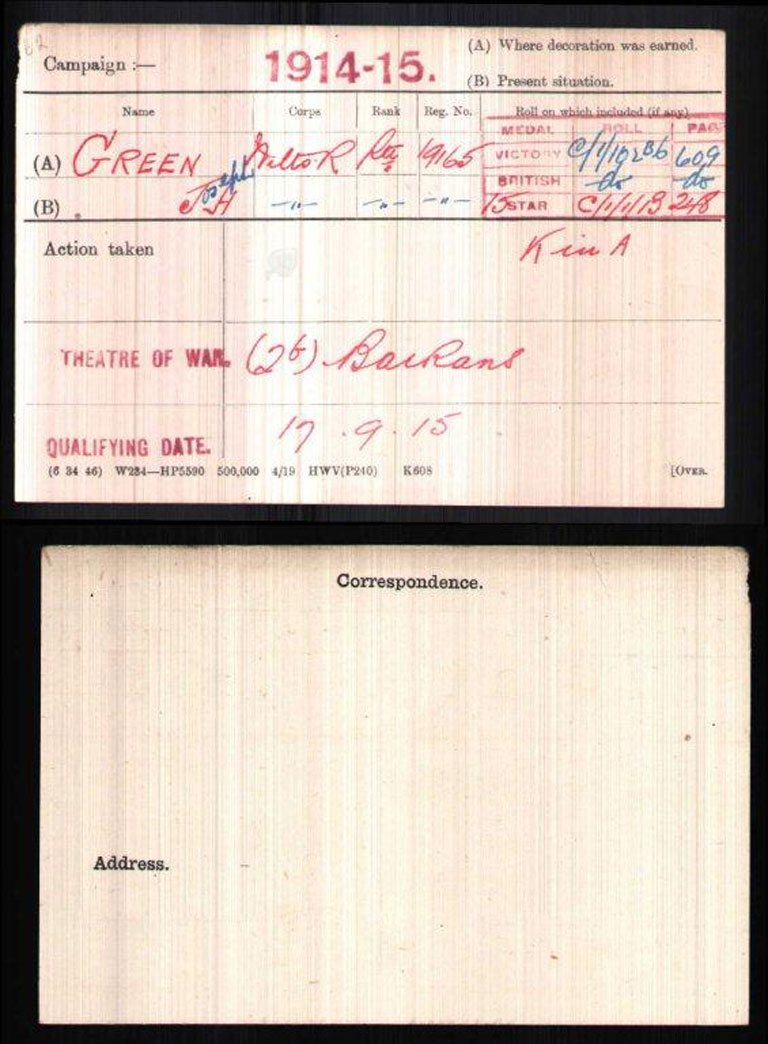

Joseph’s service papers do not survive, as so many do not. His Medal Rolls Index Card shows that Joseph arrived in the Balkans on 17 September 1915, a private in the Duke of Edinburgh’s (the 5th Battalion of the Wiltshire Regiment). The 5th Battalion was formed at the outbreak of the First World War and was a service battalion. In June 1915, the division joined the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and saw the rest of the war out in the Mesopotamia.

Joseph served all of his time in Mesopotamia, arriving partway through the Gallipoli campaign. He survived Gallipoli before the battalion moved to Iraq.

The war diaries make for grim reading. Smallpox swept through the camp whilst Joseph was out there, and the conditions sound a far cry from deepest darkest dearest Wiltshire. As a mere private, of course, there was little hope of finding him mentioned by name, but the war diaries are an unparalleled source for scene setting.

Joseph was at least among familiar faces. Or at least one familiar face. His brother in law, the husband of his little sister Rhoda, Alfred Edwin Tilley was also serving with the 5th though he had begun his service almost a year exactly before Joseph. Despite the gap in service, both men were killed in action on the same day, 5 April 1916. Without Joseph’s attestation papers or service record I cannot tell how long he was in training prior to his deployment. 280 men were killed the day that Joseph died, with 29 men lost from the Wiltshires in total.

Alice’s oldest brother Samuel also had a history with the Wiltshire Regt. His service number suggests that he had signed up in 1906, and is firmly ensconced with the regiment by the time of the 1911 census. A Lance Corporal, he survived the war, returning home to his wife, and his sister. His medal card shows he was awarded the Victory and British Medals, the 1914 Star and Clasps, and the Silver War Badge. Alfred received all of the above, except the SWB, and Joseph received the same but was awarded the 1915 Star as his service was later. Alfred is commemorated on the war memorial in All Cannings. Joseph, strangely, is not, nor does he appear on the memorial in Bishops Cannings. I wonder what the why of this is, exactly and if any Wiltshire readers can advise, I would be grateful for any input.

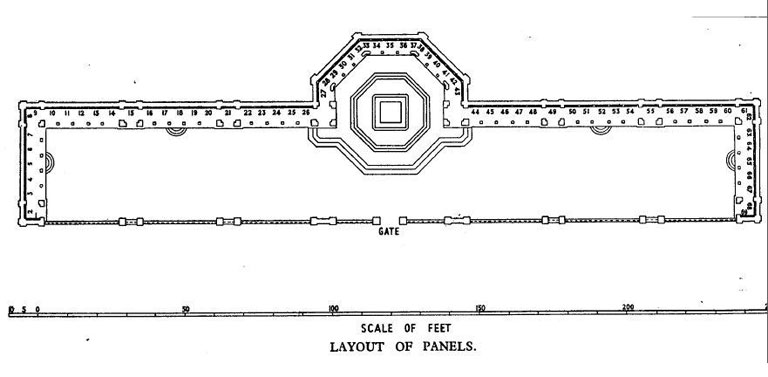

Joseph and Alfred’s deaths are commemorated in Iraq with another 40680 men, on the Basra memorial. The memorial has survived recent warfare in Iraq, as far as the CWGC can tell, but additional provision has been made for commemoration at their HQ in Maidenhead until such time as the CWGC can access the memorial again.

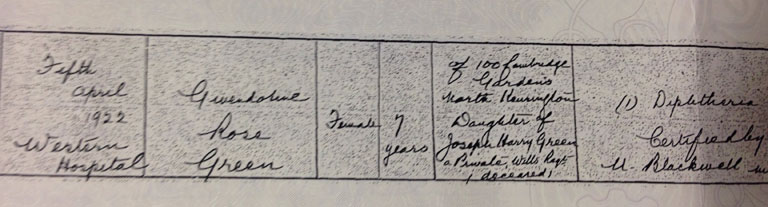

By the time of his death, Joseph and Alice had had a further three children after those listed in the 1911 census. Two sons and four daughters. Joseph’s youngest daughter Gwendoline’s birth was registered in the spring of 1915 and she can barely have been six months old when her father left England. Upon his death, Alice found herself aged just 28, a widow with six children under the age of eight. At some stage she took the children up to London, for the family consider their roots in part in South London. It can’t have been an easy move to make, leaving all that was familiar behind to move to a strange city so unlike the village she came from. At this point, it would be rather useful to have the 1921 Census to hand, but that will have to wait for a few more years before it yields its treasures of information. Sadly, Gwendoline died as a little girl, but the others grew up and lived long lives.

I was interested to note that Joseph was mentioned on Gwendoline’s death certificate, even though it was almost exactly six years since he had died.

The Green name lives on, though no longer in Wiltshire. Alice, so far as I can tell, never remarried and died in the 1970s in her home county.

This isn’t the most satisfactory of summaries. No service records, no letters, no photographs, just the fragments of a family history gleaned from the official records. A brief skim through the Devizes newspapers revealed no mention of either of these two men though I suspect that to be my looking in the wrong place rather than there actually being no mention. I hope to be able to update this entry a little further down the line. Writing this did remind me though that there is an awful lot of focus on the men who served, and to my mind somewhat less on the people left behind when we talk about commemoration. Those who kept industry running and raised families, whilst no doubt hoping and praying for five years that their loved ones would be returned to them safely. We know that not all of them were so lucky, Alice amongst them.

Richard van Emden’s book “The Quick and the Dead” is an interesting look at the wider impact of the war (available from our bookshop). As the blurb states:

“more than 192,000 wives had lost their husbands, and nearly 400,000 children had lost their fathers. A further half a million children had lost one or more siblings. Appallingly, one in eight wives died within a year of receiving news of their husband’s death”

and:

“Very few people know that only the first minute’s silence on Armistice Day is in memory of the dead of the Great War and all the subsequent wars.

The second minute is for the living, the survivors of the war, and the wives and the children they left behind.”

Excellent short story and coincides with that of my great uncle Sgt JC Raine of Bradford on Avon who was also of the 5th Wiltshires. He died on the same day and the same place in what is now Iraq.

Thanks for your comments Chris. I did see your Great Uncle’s name on the list too. I idly began to consider researching all the Wiltshire Regt. men who died that day, but haven’t quite gotten around to it as there are over 70! I’d be delighted to learn more about the men he served with, though.

My grandfather, Herbert Archibald MARTIN (1878-1963) served in the Somerset Light Infantry and Royal Engineers on the North West Frontier in India (now Pakistan) and later in Mesopotamia.