James Stanley Crossley at military camp in Ripon, August 1911.

In March 2013, I wrote a blog focusing on the case of my maternal great-grandfather, Ernest Butterworth, who voluntarily enlisted in the Army Reserve in December 1915 at the age of 38.

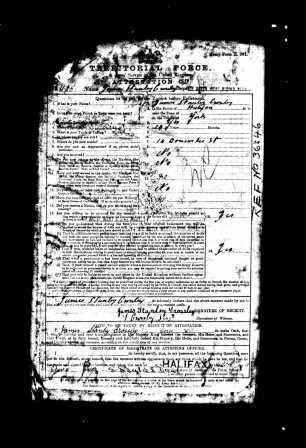

This time, I’m shifting attention to my paternal side, specifically my grandmother’s first cousin, James Stanley Crossley. On 20 June 1911, he enlisted as a boy soldier in the Territorial Force (TF), a volunteer reserve component of the British Army.

The TF was established under the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907, and was essentially a home defence force for service during wartime. James Stanley was with the West Riding Military band and played the clarinet. He was attached to the 1/4 West Riding Regiment (Duke of Wellington’s Regiment) on 20 June 1911. His age is listed as 14 years 0 months; in fact he had just turned 12, and measured 4ft 9 ½ in height with a 30 in girth. His father was witness to the information supplied; he was also in the TF, aged 36.

The number of boy soldiers recruited would substantially fall after the Battle of the Somme when conscription was brought in and recruits had to provide proof of age.

Extract from Army Service record (Territorial Force) of James Stanley Crossley (catalogue reference: WO 363/C1386)

Known as Jimmy to family and friends, James Stanley was born in Halifax in West Yorkshire on 24 March 1899 and was the eldest son of Frank and Lavinia Crossley. He can be found on the 1901 census, recorded living at his birthplace, Moorhouse Cottage, aged 2, with his mother and older sister Doris, aged 3.

In the 1911 census, he is resident at 14 Doncaster Street, Salteskebble. By then, in addition to Lavinia and Doris, he is recorded with his younger siblings, Donald Edmund, aged 5, and Frank, 10 months. His occupation is listed as Scholar when the census was taken on 2 April 1911, but, within three months of it, he had enlisted in the British Army, aged 12 years and 85 days. It is not clear how long his father served with the TF but his absence from the family home in the 1901 census may indicate he had served for some time.

Although he spent the first five years at training camps and firmly in the UK, Jimmy was posted overseas in July 1916. This is because he volunteered for the Imperial Service Section and agreed to serve abroad in times of war.

Family portrait, probably taken shortly before Jimmy was posted overseas in 1916

As such, his service record shows that he entered the theatre of war on 20 July 1916, arriving at Etaples, following a disastrous month for the British Army where over 60,000 men fell on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Posted to the field on 13 August 1916, Jimmy was killed in action just three weeks later on 3 September. Having served in a theatre of war, he was entitled to Victory and British War campaign medal, as well as the Territorial Force War Medal. Both would have been issued to his next of kin.

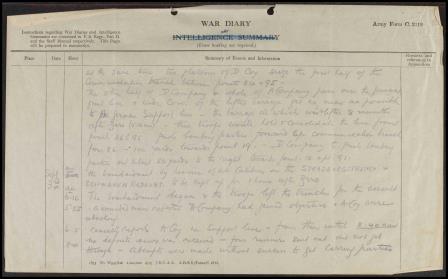

The 1/4th Battalion were in the 147th Brigade, part of the 49th Division, and the attack made on 3 September 1916 remains one of the most important events in the Battalion’s history; never before had it been selected to play such a key role. Unfortunately, casualties were so high that day that an accurate account of what took place is missing: nearly all the officers and senior non-commissioned officers did not live to recount the events.

The operation was part of a big attack, made at dawn on both sides of the River Ancre. The 4th Battalion was supported by the 5th, 6th and 7th Battalions alongside the 146th Infantry Brigade – but the 4th Battalion was on the extreme flank and ultimately exposed. As dawn broke, the attack began in the directions of the Schwaben Redoubt and the Pope’s Nose. The enemy attack embraced most of Thiepval Wood, and casualties were high as a result of heavy bombardment and snipers’ attacks. The total number of casualties from the 1/4th Battalion were 11 officers and 336 other ranks, including Jimmy. During the next few weeks several divisions tried and failed to carry the objectives of 3 September.

‘The History of the Great War’ was published in the 1920s and is based on official documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence, many held at the National Archives. The account of the 147th Brigade from 3 September summarises without compassion its failure:

‘There was little fault to find with the artillery preparation and support: but a frontal attack, with no attempt at surprise, upon this portion of the original German defences, commanded as it was by Schwaben Redoubt, seems to have offered little chance of success. Moreover, the troops were very tired, and in the attacking battalions were many partially trained reinforcements posted from many different regiments. These men displayed a certain apathy and lack of determination, in sharp contrast to the devotion of the platoon leaders who died with their usual gallantry, and to the splendid resolution of the older soldiers. It is but fair to add that so inexperienced were some of the new arrivals that when they were called upon to follow the British barrage they thought they were asked to walk into a German one.’

Commanding Officer’s War diary entry for 147 Infantry Brigade: 1/4 Battalion Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment), 3 September 1916 (catalogue reference: WO 95/2799/2).

The Commander War Diaries at Kew do indeed confirm that Jimmy’s 1/4 Battalion took turns in line with the 1/5 Battalion advancing near Thiepval Wood. In the period leading up to that fateful day, the Battalion noted the British dead still uncleared from the battlefield, ‘the sunken Thiepval Road crowded as it was with the bodies of Ulstermen who had fallen or crawled there to die on 1 July’.

The Battalion reached Raincheval on 19 August, then Forceville on 27 August, before reaching Martinsart Wood on 2 September.

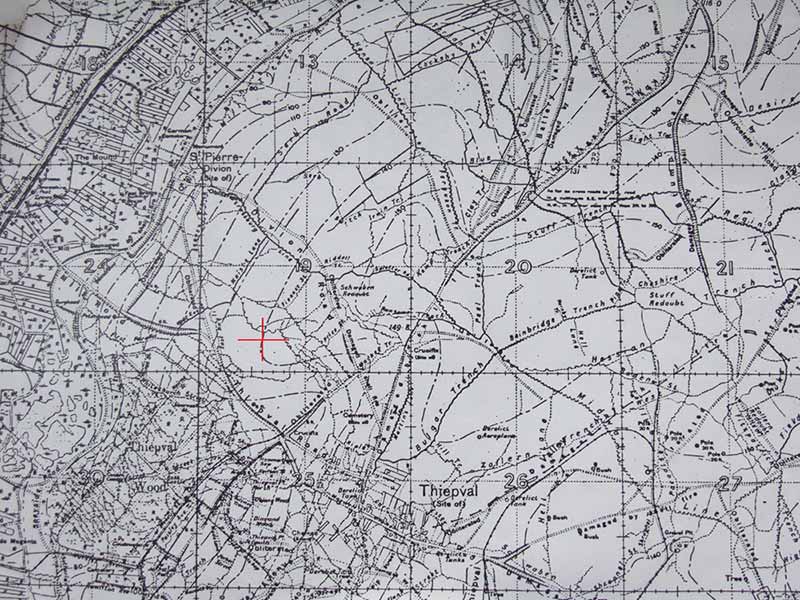

But what became of the 347 casualties, including Jimmy? A substantial number of West Riding Regiment men who died in this attack are buried in Mill Road Cemetery. But, like so many of his comrades, Jimmy was buried where he fell in the mud field. His body was not found until 1927. The exhumation report shows he was found at map ref 57d.R.19.c.6.3. just outside Thiepval Wood, being identified by his dog-tag.

Map with a red cross showing where Jimmy’s body was found

Gravestone for James Stanley Crossley located at Serre Road Cemetery Number 2

He is buried at Serre Road No 2 cemetery. This cemetery is one of the bigger ones on the Somme and is almost entirely of men who were found on the battlefields quite a while after the end of the war. There are now 7,127 Commonwealth burials of the First World War in the cemetery, mostly dating from 1916. Of these, 4,944 are unidentified. The cemetery, which was not completed until 1934, was designed by Sir Edward Luytens.

I visited his graveside in May of this year and noticed his age incorrectly inscribed as 18. He was in fact 17 as his birth certificate proved. With this information, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has agreed to correct the headstone in due course.