Ernest Holloway Oldham (cat ref KV 2/808)

I never knew my paternal great uncle, Ernest Holloway Oldham. He was born in 1894, and took his own life in 1933. As a result, he was barely spoken about by my father’s generation, who were too young to remember him; even the manner of his death was hushed up.

The reason became clear a few years ago, when an intelligence file was released about Oldham. It stated that he’d been dismissed from his job as a cipher clerk at the Foreign Office for drinking, but his departure in 1932 revealed a dark secret – he’d been living a double life selling secrets to Soviet agents for several years. Security agents were swiftly dispatched to monitor Oldham’s activities but as his life unravelled, he committed suicide.

Along with phone intercept transcripts and photographs, the file contained psychological analyses that revealed Oldham had always been of a ‘nervous disposition’, but had become even more ‘unpredictable’ towards the end, with a British agent noting that he was ‘heading for a breakdown’ just days prior to his suicide.

The file creates a general impression that Oldham was a weak man, motivated by greed to fund a lavish fantasy lifestyle of fast cars and private members’ clubs, who ended up out of his depth – pressurised by his Soviet handlers who were aware of his mental state yet continued to squeeze as much information out of him as they could, and living in constant fear of discovery by the British.

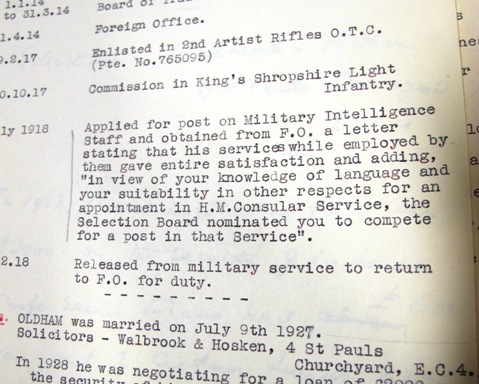

The intelligence file contained a tantalising reference to his First World War military service records, which had been requisitioned from the War Office to provide some background to his activities. However, no documents could be found beyond a basic summary that showed he had enlisted on 9 February 1917 with the 2nd Artists Rifles Officer Training Corps, and had been granted a temporary commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry on 31 October 1917.

Frustratingly, there is no surviving service record for him amongst the temporary commissioned officers in series WO 374. Perhaps more surprisingly, there’s not even a campaign medal index card. A search of the monthly Army Lists for 1917 and 1918 showed he’d been attached as a temporary officer to the 5th Battalion, before moving to the 1st Battalion on 12 February 1918.

The unit war diaries for the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry provide details about Oldham’s movements, including several references to him by name. The contrast between his career behind a desk at the Foreign Office in Whitehall, and his fourteen months on the western front, could not have been greater. Oldham arrived with the 5th Battalion in time for the final stages of the Battle of Passchendale, part of the third Battle of Ypres, only to be transferred to the 1st Battalion to face the German’s ‘Spring Offensive’ , an assault on the trenches defended by Oldham’s unit on 21 March 1918 as part of Operation Michael. The war diary records that the battalion:

‘Inflicted enormous losses on the enemy; before the retirement to the Haig Line those of the Battalion (the great majority under Colonel H M Smith DSO) seeing themselves surrounded, determined, to fight to the last. Owing to the fact that very few got away from this melee very little is known of the actual details of this fight. Sunset found a handful of the Battalion under Lieutenant A B Rogers MC still in the Haig Line.’

The fighting continued the following day:

‘The remnant of the Battalion wedged between 1st [Battalion] The Buffs and 2nd [Battalion] Yorkshire and Lancasters put up a desperate fight in the Haig Line. About 3pm, unsupported by artillery who were moving back, the enemy having succeeded in outflanking the line in overwhelming numbers, it became necessary to fall back on to Vaulx. The retirement was conducted in good order. At dusk the Battalion received orders to withdraw to the GHQ line behind Vraucourt. In this the heaviest fighting the Battalion has ever known, ie 21-22 Mar 1918, the Battalion loss was in ‘Killed, Wounded and Missing’ 21 officers and 492 other ranks, and earned for itself the admiration of all who fought with them and added fresh laurels to the history of a gallant regiment. Only 77 other ranks survived on the evening of the 22nd of those who were in the battle.’

Oldham was amongst the survivors, and remained with the battalion during the following months. According to the security file, he applied to join the Military Intelligence Corps in July 1918, supported by a good character reference by the Foreign Office. However, it looks like his application was unsuccessful because he returned to the unit just in time for the start of the Hundred Days Offensive in August 1918. He was involved in the battalion’s assault on German positions in St Quentin’s Wood on 18th September, with raids commencing from Trout Copse at 05.20 hampered by torrential rain, thick mist and bombing raids by German aeroplanes. The battalion was subjected to heavy machine gun fire from their right flank, with fighting growing ‘very bitter’.

With many objectives either missed completely or unable to be held, a second assault was ordered for the following morning; operational orders were hard to read because of the darkness, with the result that the attack was mired in confusion.

‘C Company was again held up by intensive machine gun fire from right flank. B Coy fought its way into Fresnoy le Petit meeting stubborn resistance and suffering heavy casualties including the two remaining officers and entirely losing touch with the remainder of the Battalion. Throughout the day the several small parties of which the Company was now composed resisted all attempts of the enemy to surround them. At dusk being still isolated these parties withdrew still fighting on to our line of posts.’

The diary notes that 176 other ranks were casualties of the fighting, along with five officers. 2nd Lieutenant E H Oldham was named amongst them. We can only presume that he was taken to a mobile field clearing station or field ambulance, before additional treatment behind the lines. There is no further note in the war diary that Oldham returned to the depleted battalion for the remainder of the campaign, when they eventually broke through the Hindenburg line and fought right up to the Armistice on 11 November 1918. According to the intelligence file, Oldham was demobilised on 11 December and returned to the Foreign Office to resume his career as a clerk, though he remained on the reserve list until 1920.

My great uncle’s subsequent actions in the 1930s cannot be condoned or defended in any way. Reading the intelligence file, Oldham was considered a traitor to his country, causing incalculable damage which assumed even greater significance in the 1950s. However, researching his military service makes it slightly easier to understand (though not excuse) why he tried to escape everyday life on his return and why he was of a ‘nervous disposition’ having faced shells, machine guns, gas attacks and the terrible conditions of the Western Front. Along with hundreds of thousands of other veterans who returned home emotionally and physically scarred, we can never fully appreciate the impact of the conflict on their lives; and therefore somewhat paradoxically, Oldham should also be treated as a war hero.

I’m afraid you shouldn’t have assumed that being a temporary officer would mean his record would be in WO 374. Using WO 338/14 p643 (of the pdf available online) we can see that Oldham, Ernest Holloway, and his unit indicated by 53 – which was the pre-reform number of the KSLI, had a Long Number file (ie WO 339) with the Long Number 211543. Searching in Discovery with the Long Number used as the Former Reference shows this file is now catalogued as WO 339/112210, Oldham E (obviously the recataloguing project hasn’t got quite that far yet).

As to the lack of MIC, I believe officers had to actively apply for their medals (though they were issued automatically to rank and file), so potentially he simply never claimed them.

Hi Nick,

I found it interesting reading about your account of your great uncle, Ernest Holloway Oldham.

I have been doing some research into Oldham via Soviet sources. Did you know that his Soviet controller, Dmitri Bystrolyotov, confessed to having him murdered?

Did you know that your great aunt, Lucy Oldham, was also part of the network (codename MADAM). Walter Krivitsky defected in 1939 and informed MI5 of the Soviet spy-network that included the Oldhams, John Herbert King and Henri Pieck. This information led to the arrest and imprisonment of King. Only after the war, in October 1945, did MI5 arrange to bring Pieck over to London with the object of meeting Lucy Oldham. The MI5 file report shows that Lucy Oldham threw herself into the Thames at Richmond in 1950. According to Gary Kern: “The timing of her demise, apparently fortuitous for the NKVD, raised suspicions that she had been silenced.” Do you know anymore about that?

It seems that Ernest Oldham was the first of Britain’s Soviet spies. According to John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, the authors of Deadly Illusions (1993): “Because of British secrecy, the significance of the Oldham case has remained undisclosed and underestimated. The truth, as revealed by NKVD, files is that Oldham was not just a code clerk but a cypher expert who developed codes and was therefore able to provide Moscow with a great deal of information on security and secret traffic systems. The resourceful Bystrolyotov, who operated under the alias of Hans Gallieni in England, had also obtained from Oldham not only the keys to unlock a considerable volume of British cypher cables but also the names of the other paid members of the Communications Department who became targets for Soviet recruitment.”

You can see what I have here:

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/Ernest_Oldham.htm

If you follow the links you will find out about the rest of the network.

John Simkin

Hi John, The link is not working. Is this source still available?