In 1902, a French film, A Trip to the Moon, related the extraordinary journey of a group of astronomers who travelled to the Moon in a cannon-propelled capsule. At the time, a trip to the Moon was pure fantasy. Yet, less than 70 years later, it became reality.

Fifty years ago, on 21 July 1969, astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were the first men to walk on the Moon, while their colleague Michael Collins was waiting for them in lunar orbit. The story of Apollo 11 is well-known and well-documented, and it is not my intention to tell it all again. The documents held at The National Archives, however, give a good impression of how the lunar adventure was viewed from Britain.

Britain had always had a keen interest in space policies. When the Soviet spacecraft Luna 2 reached the surface of the Moon on 13 September 1959, the only person who wasn’t very excited about it was the Foreign Secretary, Selwyn Lloyd, who ‘said in a moment of irritation to a reporter who badgered him on the tarmac: “I don’t think many people are terribly interested in the Russian rocket”’ (PREM 11/3995).

At the beginning of the 1960s, the Soviets were definitely winning the Space Race. In October 1957, they had successfully launched a satellite, Sputnik 1, into orbit. It was followed in November by the launch of Sputnik 2, which carried one of the most famous dogs in history, Laika, a stray mongrel picked up from the street in Moscow (sadly, she died within the fourth orbit round). On 12 April 1961, Major Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit around Earth.

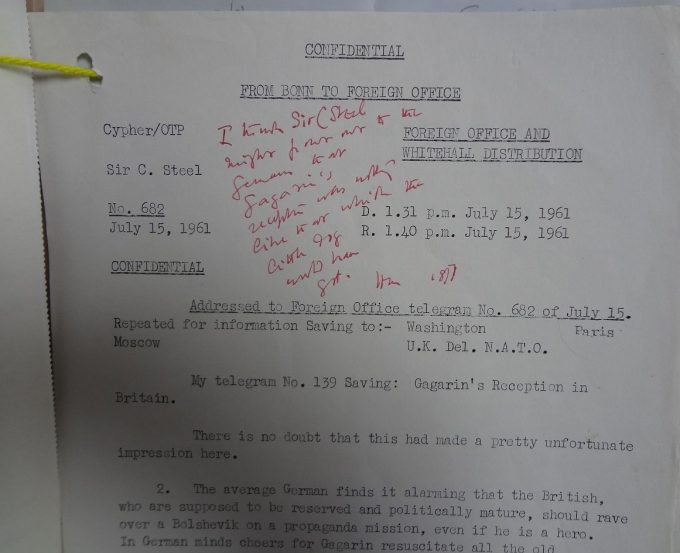

Gagarin visited the UK in July 1961, and was received as a hero wherever he went. The British ambassador to West Germany, Sir Christopher Steel, reported:

‘the average German finds it alarming that the British, who are supposed to be reserved and politically mature, should rave over a Bolshevik on a propaganda mission, even if he is a hero’.

The British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, commented:

‘I think Sir C. Steel might point out to the Germans that Gagarin’s reception was nothing like that which the little dog would have got’ (PREM 11/3543).

Christopher Steel’s telegram and Harold Macmillan’s comment, 18 July 1961 (catalogue reference: PREM 11/3543)

On 25 May 1961, at a Joint Session of Congress, John F Kennedy delivered a speech on ‘Urgent National Needs’. He said: ‘I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth’[ref]The speech can be viewed here.[/ref].

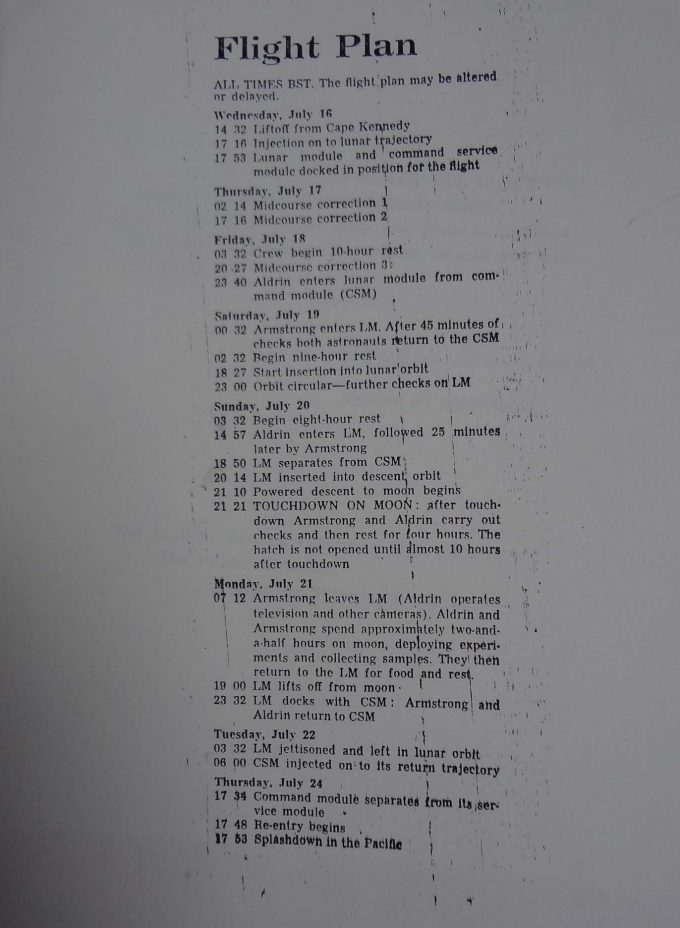

At the time, the Americans had only managed to send a single astronaut into space, and not even into Earth orbit. By 1969, against all odds, the United States were ready. The Apollo 11 Mission, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, would fly to the Moon from Cape Kennedy, Florida, on 16 July 1969 at 14:32. The Lunar Module, Eagle, would separate from the Command Service Module (Columbia) on 20 July at 18:50, and Armstrong and Aldrin would touch down at 21:21. The hatch would not be opened for at least ten hours. The astronauts would spend about two and a half hours on the surface of the Moon on 21 July to collect samples before reuniting with the Command Service Module on the 22nd. Splashdown in the Pacific was scheduled on 24 July at 17:53 (PREM 13/3012).

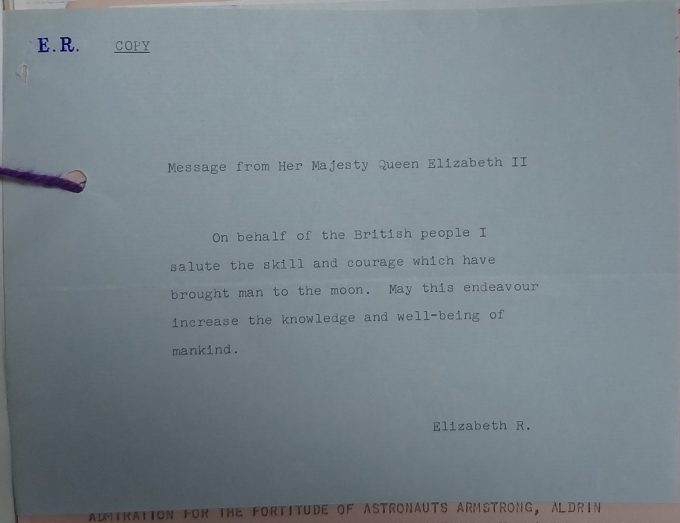

While the astronauts were getting ready for the most important flight in their career, officials in Britain were discussing the message they wanted to be carried to the Moon. On 23 June 1969, the British ambassador to the United States, John Freeman, reported that NASA had invited the governments represented in Washington to send messages to the Moon, and asked whether the Queen would like to write one.

J C Thomas, of the Science and Technology Department, thought that it was ‘one of those ideas that may look slightly silly, but which are apt to catch people’s imagination’. John Graham, the Principal Private Secretary to the Foreign Secretary, agreed, and added that ‘their idea of emphasising the international aspect of the first man on the moon is something we want to support’. Besides, they concluded, ‘it would look churlish’ to decline the invitation. Buckingham Palace thought the idea was ‘a gimmick’, and added that it was ‘not the sort of things [the Queen] much enjoyed doing, but she certainly would not wish to appear churlish by refusing an invitation which is obviously so well-intentioned’ (FCO 55/351).

The Queen’s message, carried to the Moon along with those of about 70 nations, read:

‘On behalf of the British People I salute the skills and courage which have brought man to the moon. May this endeavour increase the knowledge and well-being of mankind’ (FCO 55/351).

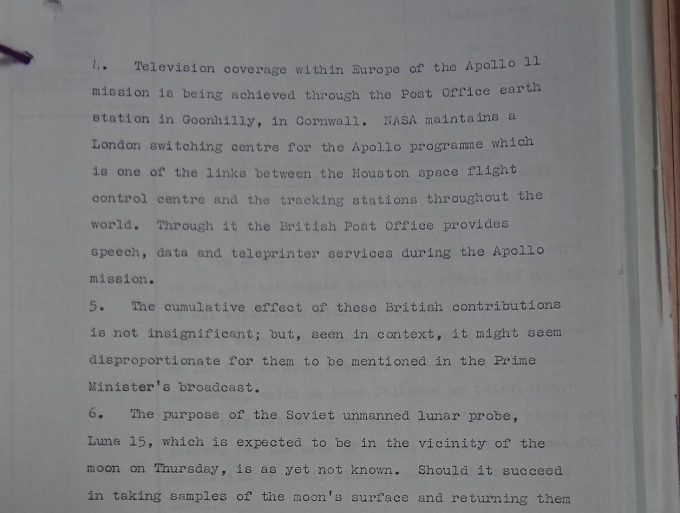

As Armstrong and Aldrin were waiting in the Lunar Module, Prime Minister Harold Wilson broadcast a message on television. ‘We must all be filled,’ he said, ‘with a profound sense of wonder and admiration in witnessing this historic event’. The briefing papers the Prime Minister was given ahead of the broadcast debated whether it would be appropriate to mention the British contribution to the Apollo Programme. The UK had indeed made ‘a modest contribution’ to the programme. The fuel cells were ‘based on the Bacon cells’, while ‘the water-cooled undergarments of the astronauts’ space suits were developed from designs made by the Royal Astronautical Establishment, Farnborough’. Besides, ‘television coverage within Europe of the Apollo 11 mission [was] being achieved through the Post Office earth station in Goonhilly, in Cornwall’.

It was decided, in the end, not to mention any of the above. ‘The cumulative effect of these British contributions,’ the briefing note conceded, ‘is not insignificant, but, seen in context, it might seem disproportionate for them to be mentioned in the PM’s broadcast’.

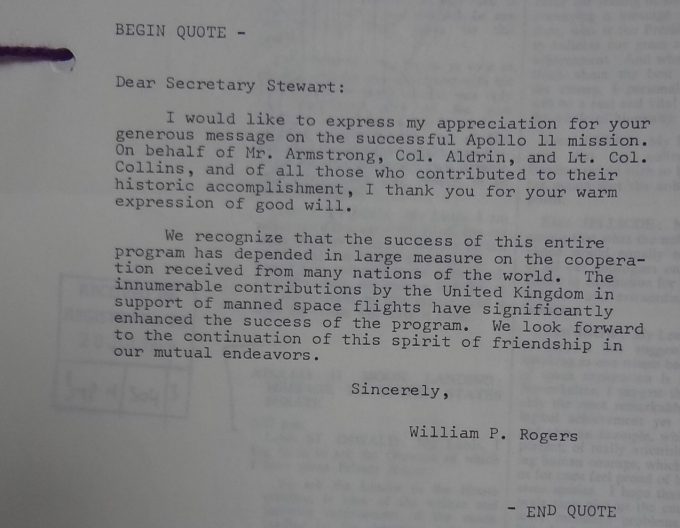

The British contribution didn’t go totally unnoticed, though. The Foreign Secretary, Michael Stewart, sent a message of congratulations to the American Secretary of State, William Rogers. In his response, Rogers thanked Britain – ‘the innumerable contributions by the United Kingdom in support of manned space flights,’ he wrote, ‘have significantly enhanced the success of the program’ (FCO 55/351).

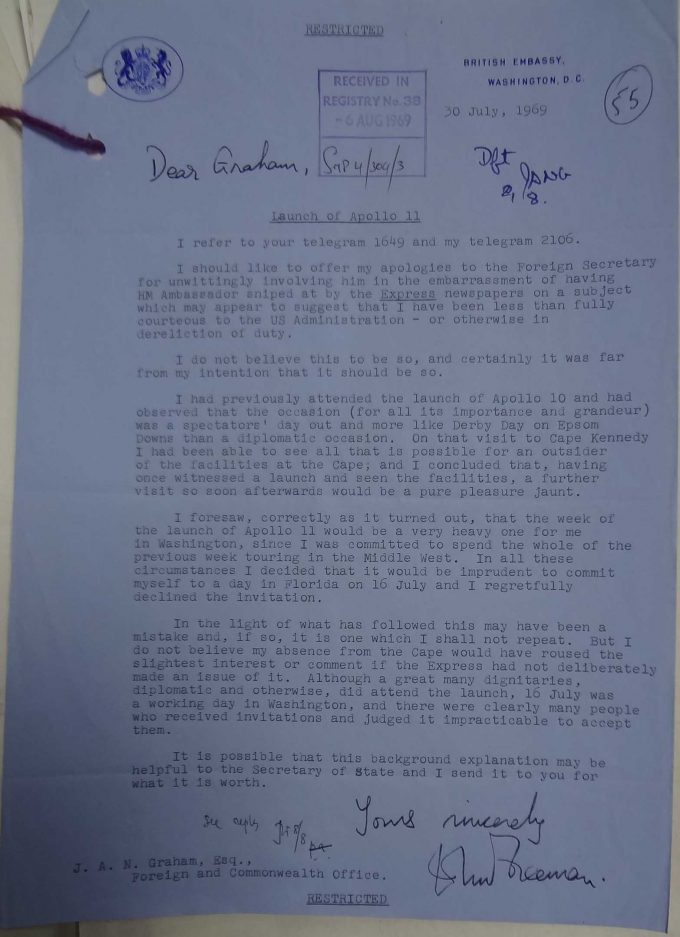

Another thing which didn’t go totally unnoticed was the absence of the British Ambassador at Cape Kennedy on 16 July. John Freeman probably missed the event of the century when he decided not to attend the launch of Apollo 11. Having already attended the launch of Apollo 10 on 18 May, he explained, he ‘concluded that having once witnessed a launch and seen the facilities, a further visit so soon afterwards would be a pure pleasure jaunt’. He apologised for his ‘mistake’, but was convinced that no one would have noticed his absence ‘if the Express had not deliberately made an issue of it’ (FCO 55/351).

The Apollo 11 Mission had the success we know. Once the astronauts were safely reunited with the mothership, Harold Wilson sent a message to President Nixon – a message with which I’m confident we can all agree: ‘this epic voyage of discovery is an inspiration to us all’ (PREM 13/3012).

Even Soviet scientists were suitably impressed. Space scientist and diplomat Anatoli Blagonravov, for instance, found it amazing that it had been ‘possible for the Americans to reach the Moon with an exact timetable’, and offered warm congratulations to the astronauts (FCO 55/348).

©NASA, as11-40-5903. Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., lunar module pilot, walks on the surface of the moon near the leg of the Lunar Module (LM) “Eagle” during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity (EVA). Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, commander, took this photograph with a 70mm lunar surface camera

It is safe to say the whole world rejoiced when Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins made it back to Earth in one piece. In Hong Kong, they were slotted into tradition and appeared on giant signboards outside bakeries during the mid-autumn festival, famous for its mooncakes. The Hong Kong Government Information Services reported:

‘When the three Apollo 11 astronauts returned from their historic mission recently, they brought back with them more than just samples of the lunar soil. What else did they bring back? Mooncakes of course……… given to them by a goddess. This delightful version of what happened when the first man landed on the moon is how many bakery shops in Hong Kong are depicting the event on huge picture signboards’ (CO 1069/468).

- Mooncake festival signboard, Hong Kong, 1969 (catalogue reference: CO 1069/468)

- Mooncake festival signboard, Hong Kong, 1969 (catalogue reference: CO 1069/468)

One thing the astronauts did really bring back was moon dust. Some of it was presented by Richard Nixon to Harold Wilson during his visit to Washington in 1970. This ‘gift to the British People’ consisted of ‘four minuscule pieces embedded in a clear plastic globule mounted for display’; it came with ‘a miniature Union Jack which was taken to the Moon’. The gift went on display at the Science Museum in London before going on a nationwide tour (PREM 19/1906).

The moon dust finally returned to No 10, where Prime Minister Edward Heath was allegedly ‘unable to identify a sufficiently public spot (…) aesthetically suitable for locating the contemporary style display stand’. It then apparently ‘languished for several years’ in a cupboard, in which it was discovered quite by accident in 1979. No 10 wasn’t entirely sure what to do with it. An official noted: ‘it would certainly not enhance the appearance of any of the No. 10 State Rooms’, but conceded that ‘it ought to be on public display somewhere’ (PREM 19/1906).

In 1985, No 10 approached the Director of the Science Museum, Dame Margaret Weston, to see if they wanted to borrow it again. The response was less than enthusiastic:

‘As a curiosity (ranking with a tooth-brush once used by Napoleon which they have at the Museum) they would always be very willing to give it a home if we no longer wanted the exhibit at No 10, but more significant specimen of moon rock are apparently now available from NASA if required as part of a scientific display’ (PREM 19/1906).

Dame Margaret ‘further volunteered that it was not really a very exciting exhibit’.

Gift of moon dust from US President Nixon during PM Wilson’s visit to the USA in 1970 (catalogue reference: PREM 19/1906)

Of course, by 1985, much time had passed since the Apollo 11 Mission’s ‘epic voyage of discovery’. Five other Apollo missions had landed on the Moon. Ten other men had walked on the lunar surface. The space programme had moved on.

You may or may not like the display; you may or may not feel a bit blasé about moon landings now that we are able to conduct experiments much further away in outer space; you may or may not be interested in astrophysics. Still, the fantastic achievements of all the men and women working on Apollo 11, Neil Armstrong’s famous ‘small step for a man, giant leap for mankind’, and the photographs taken by the astronauts capture the imagination. In July 1969, men have, for the first time and under the eyes of millions of people on Earth, walked on the Moon and returned safely, showing that fantasy could become reality and dreams come true.

After the tragedy of Apollo 1, the Apollo 11 crew also demonstrated that their colleagues Gus Grisson, Edward White and Roger Chaffee hadn’t died in vain in the fire that had engulfed the cabin on 27 January 1967. As president Johnson wrote to Prime Minister Wilson on 11 June 1966, ‘I have the strong feeling that if we are wise and earnest, what is happening in outer space can help us live better together on earth’ (PREM 13/3012).

A small selection of documents relating to the Space Programme will be on display at The National Archives until December 2019.

The files also contain the draft message in the event that the astronauts didn’t return safely.

where is the UK flag and moon dust now ?

In your latest email you write “…Yuri Gagarin successfully orbited the Moon in 1961…” I don’t think so !

yours

Chris Hicks

Those were the four specks of dust that people were queuing round the science museum to look at. I was so disappointed being driven back home without seeing them. More recently my school hired some NASA moon samples, more specks of dust encased in scratched plastic and was able to see them close up, including bits of the “orange soil” of Apollo 17, not really so orange close up. And now the children look a little bemused at these bits of dust in a science lesson Even the teachers are clearly not impressed having themselves been born 30 years after the event, there is not much of the original excitement left. Only people of a certain age, like myself, find wonderment again and a tinge of sadness over a bygone age.

The email received, which has links to the very fine blog posting, nonetheless had a startling error/typo: the blog accurately says that “On 12 April 1961, Major Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit around Earth.”. However the email text in error said he orbited the Moon!! (“… Gagarin successfully orbited the Moon in 1961” [sic])

I was a newspaper boy then, and followed these things – it would have been inconceivable news that he was propelled beyond Earth’s limits into a lunar orbit & safely returned without anyone noticing and the Soviets even more prominently celebrating this brave cosmonaut!! Cheers – regards, K. Peel

Thank you for this summary of the Apollo 11 mission.

As a 22 year old electronics under graduate I could hardly believe my eyes and ears that this was really happening and the significance still strikes me 50 years later.

Having been brought up on Dan Dare of the Eagle comic and Flash Gordon at Saturday morning cinema, it was incredible to the the start of the Space Age in my lifetime. ..I will be discussing this article with my Grandsons , 7, 5 and 4 years old.

The recent Moon Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum came to mind, when I read your excellent blog on the Apollo 11 Landing, and also led me to recall Patrick Moore’s intricate connection with it. In his autobiography, Sir Patrick wrote of being asked to write a Moon Flight Atlas. ‘I wrote the book at breakneck speed. It was published within a month of the lunar landing.’ His close association with Neil Armstrong and ‘Buzz’ Aldrin led to him presenting Patrick with a BAFTA award in 2001. Buzz said that Sir Patrick’s ‘special subject has always been the moon…In 1959, he was able to bring viewers of his television programme The Sky at Night direct pictures of the far side of the moon. Sir Patrick’s records were used by NASA in the early Apollo landings.’… I once talked with him – a friend of many years – as being the ‘master stargazer’. ”No,’, he replied, “I’ve always thought of myself as a ‘moon gazer’ “!