Between June 1908 and November 1917 there were 63 injuries to the thumbs of Barry Railway employees in South Wales. The injuries ranged from strained and sprained thumbs, to thumbs which were cut or crushed, thumbs with splinters and thumbs which had to be amputated. Apparently 36 of these injuries were to thumbs on the left hand and only 24 were right hand thumbs (with three thumbs unspecified).

So why might this be? Well, as a rule of thumb, most people are right-handed and so the right thumb is more likely to be stronger and less prone to injury, and on the other hand the left thumb (on a right-handed person) is less adept at handling things (literally).

Barry Railway accident report extract RAIL 23/57

For example, Lewis Lambert, a Smith’s apprentice, was working in the Smith’s Shop in Barry on 22 November 1913 when he sprained his left thumb handling a large piece of iron. A couple of years later, in July 1915, he wounded the same thumb when forging a steel key on an anvil, and a piece of steel sliced into his thumb. Was the earlier strain a contributing factor in the later injury perhaps?

His workmate George Matthews worked as a fitter for the company. He had to have his right thumb amputated above the first joint after a scratch became infected in January 1912.

Some thumb injuries had very little to do with the railway as such. John Goddard worked as a packer for the Barry Railway at the Barry Docks. On 17 April 1914 he was helping a colleague put on a water suit to go down to the Deep Lock Gates, and as he fastened up the back strap the spike of the buckle penetrated his left thumb under the nail.

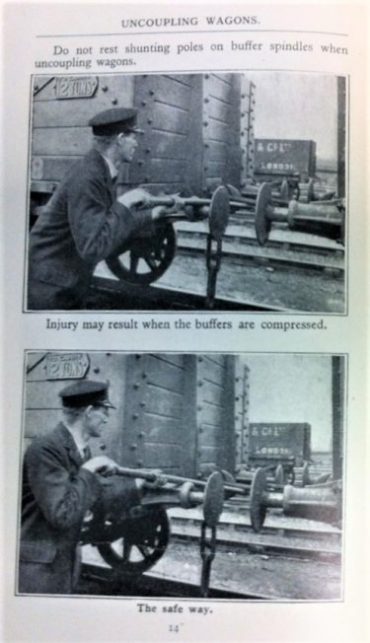

Prevention of accidents to staff engaged in railway operation booklet ZLIB 15/45/1

Each of these incidents may seem quite trivial by themselves, but each one is a snapshot of an event in the everyday life of an ordinary person a century ago. It may have been a life changing event for that person, or it may be something they forgot about the following day, but each one is recorded in the accident registers for the Barry Railway Company.

The registers are held here at The National Archives, under reference RAIL 23, and a small group of volunteers has been working its way through them, recording each accident and adding them to our online catalogue.

Aside from the details of the accidents, the registers provide basic details about the employment of each person, grades of staff employed, and local information. They provide a form of ‘staff list’ for the company at that point in time, working alongside the official staff registers for the company.

We are capturing the details of each accident, not just from the Barry Railway, but from 15 different railway companies working across Britain before 1947, which together produced over 50 volumes of accident reports.

And it’s not just thumbs. Many men died or received life changing injuries while employed on the railways, with the loss of limbs being a frequent event as men slipped under the wheels of vehicles, or got caught between two buffers with surprising regularity.

Prevention of accidents to staff engaged in railway operation booklet ZLIB 15/45/1

Individually each one may only be of interest to the descendants of the man or woman involved, but taken as a whole the data produced will enable researchers to study the development of health and safety on the railways over time.

Which companies were safer to work for, and introduced improved practices most quickly? Why were certain types of accident more prevalent than others? Were people who had been injured previously more or less accident prone in later life? How did companies continue to employ people who were disabled by their job? And to what extent were minor injuries a contributing factor in the costs of running a railway? These are some of the questions which this cataloguing work may help to answer.

The results of the data gathering exercise will also be added to the Railway Work, Life and Death database run by Portsmouth University, and hosted on a dedicated website which includes a whole host of additional background information on railway accidents.

So far we have added over 2,800 of these incidents to our catalogue, but we have many thousands more to add. If you would like to volunteer to help catalogue these records, and you can spend a couple of hours each week here at The National Archives in Kew, you can apply via our volunteers’ page.

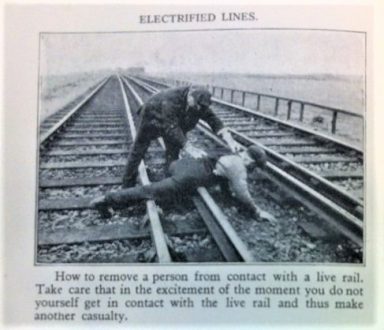

Ref: Recovering a person from the third-rail (at the photo’s time, probably 660V DC (Later 750V)

My BR safety booklet (1969) promoted body recovery via as shown jerking back on a stout “Leather” belt, but not the collar (people sweat), but by a tie (popular apparel) or use your own tie or belt to loop the victims head (reason no part of the clothing could reasoned dry)

A hard jerk, to break skin fusion to iron rail (DC Weld)

Note: Death occurs > 40mA, third-rail fed over each end via 5,000-6,500A circuit breakers.

Woking Elec Control de-commissioned 1997, opened on Heritage yearly open days…