With one week to go until ‘Files on film’ closes, this is my final blog in a series focussing on the documents featured in the competition.

In this entry, I’ve chosen to look at one of the documents we know little about from its inclusion in the collection, but further research brings it to life and establishes its importance in the history of mental health.

Please note that at the time this document was produced, ‘lunatic’ was used to describe ‘a person of unsound mind, who was once of sound mind’.[ref]1. James Lappin, 1996, ‘Central Government and the supervision of the treatment of lunatics 1800-1913: A guide to sources in the Public Record Office’, London: Wellcome Trust.[/ref] This term was used until the passing of the Mental Treatment Act in 1930, but would not be used today and can be considered offensive. For the purpose of this post, the term is used in its historical context.

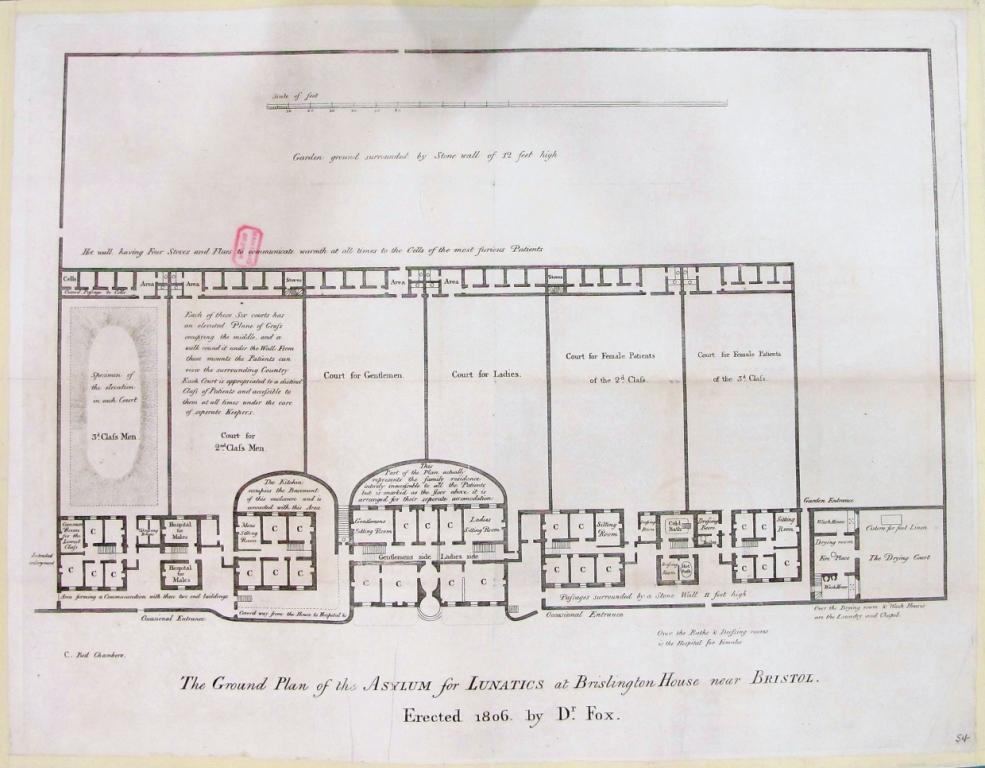

The ‘Asylum for Lunatics at Brislington House’ in Bristol was built in 1804 as one of the first purpose-built private mental institutions in the country. In MPI 1/332/1, extracted from PRO 30/8/314, we hold a floorplan of the building, showing in detail the provisions made for the patients and the way they were housed.

Provision for the care of those with mental health problems was very much in the public consciousness at the beginning of the nineteenth century due to the ‘madness’ of King George III. Where previously those with mental health problems “if harmless … were left to cope as best they could; if considered dangerous, they were confined, sometimes in degrading conditions,” public discussions of treatment, and a ‘weakening’ of the belief that lunacy was brought on by evil, became more widespread.[ref]2. a) Thomas Bewley, 2008, ‘Madness to Mental Illness: A History of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’, London: RCPsych publications; b) Nicholas Hervey, 1980, ‘ Bowhill House: St. Thomas’s Hospital for Lunatics Asylum for the Four Western Counties 1801-1869’, Exeter: University of Exeter.[/ref]

Edward Long Fox (1761-1835), founder of Brislington House lunatic asylum. Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fox_Edward_Long_grandfather.jpg

Founded by Dr. Edward Long Fox, the use of ‘moral treatment’ was the underlying principle in establishing Brislington House asylum. This more humane treatment of patients moved away from the use of restraint through chains for example, and towards the use of occupation, exercise and outdoor activity to assist with treatment and recovery. This approach, largely pioneered by William Tuke in ‘The Retreat’ in York, became the accepted practice within the public Victorian asylum system in the 19th century largely thanks to the success of private institutions such as Brislington House.[ref]3. Thomas Bewley, 2008, ‘Madness to Mental Illness: A History of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’, London: RCPsych publications, Online Archive 1: William Tuke (1732-1822) [/ref]

At the point of the founding of Brislington House, however, there were two clear paths of treatment for those found to be suffering from mental illness. Paupers were generally cared for by families, or held in parish workhouses or prisons. Private institutions, run by people such as clergymen or doctors, were aimed at wealthy patients whose families could afford to pay fees. Some patients with no private means were supported by their local parishes in such institutions, but these were the minority.

The plan is from the papers of William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, relating to hospitals. There is no further information provided with the plan itself, but patients can be seen to be divided in to ‘1st’, ‘2nd’ and ‘3rd’ class ladies and gentlemen. The document is therefore a good example of the use of our collection alongside complementary local archive collections. For example, this approach is described in a prospectus for Brislington House from 1809 held in Somerset Record Office and described in English Heritage’s listing of the property: “A prospectus … explains that the asylum’s distinctive plan was intended to allow Dr Fox to implement his therapeutic theories of segregation and classification by gender, medical symptoms, and social and financial background.”[ref]4. English Heritage, Heritage List: Brislington House and Park.[/ref] Extensive outside space was used “for therapeutic purposes, pauper patients being employed on manual work and those of middle and upper class backgrounds taking walks and exercise in the grounds.”[ref]5. Ibid.[/ref]

Records relating to the institution can also be found in Bristol Record Office’s collection and although no further information is included with the plan itself, a simple search of Discovery reveals numerous other files within our collection relating to the hospital, such as a series of individual papers of commissions and inquisitions to determine lunacy in C 211.

The asylum, with many alterations, continued to be run by the Fox family until 1952 when it finally closed. The building then became a nurses home, and has now been redeveloped in to luxury flats known as Long Fox Manor.

You can find out more about the records we hold on the history of mental health in our research guides: Mental health and Looking for records of an asylum inmate.

We hope records such as this will inspire you to make a short film and enter our competition. The film can be inspired by any aspect of any of the ten documents included in the competition. There is still time to enter, see our website for details or for inspiration, previous blogs on a West Indian view of England, bomb shelters for disabled evacuees and attitudes to lesbian relationships in the WAAF, amongst others.

The ‘madness’ of George III is now, according to some research, put down to being a blood problem and not a mental illness.

Hi David,

Yes, good point – thanks for mentioning it.

It is widely considered now that George III’s ‘mania’ was caused by porphyria. According to ‘A History of the Royal College of Physicians’ by Bewley, at the time he was treated by Reverend Doctor Francis Willis who ran an asylum in Lincolnshire. Willis reportedly told the King that due to his ideas being ‘deranged’ he was in urgent need of medical treatment to control himself, or be put in a straitjacket. The prominence of the King’s illness and its treatment brought the issue of mental health in to the public sphere in a much greater way.

Jenni