The end of the Seven Years War in 1763 saw a revitalisation of British interest in exploring the southern Pacific, as more funds became available to the Admiralty. The ship chosen for two voyages to the South Pacific during the 1760s was the frigate, HMS Dolphin. The voyages are described in several captains’ and officers’ log books now to be found in the Admiralty records.

The Dolphin’s first circumnavigation took place between June 1764 and May 1766, under the captaincy of Commodore John Byron, younger brother of the famous poet Lord William Byron. The second voyage left Plymouth on 21 August 1766. This time Captain Samuel Wallis, with master George Robertson, was in charge. George Robertson was a keen observer of the human condition and kept a valuable journal, which was later published as a book (ADM 51/4539).

Wallis and his crew left Plymouth on the 21 August 1766, accompanied by the supply ship HMS Swallow, captained by Philip Carteret. The plan was to cross the Atlantic, negotiate the Magellan Straits and then to explore the Pacific at as southern a latitude as possible to look for terra australis incognita, the supposed great southern continent.

The Straits of Magellan

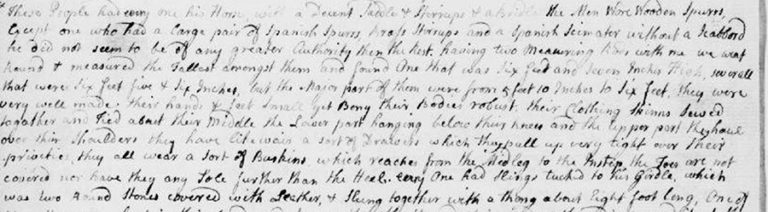

The journey across the Atlantic was relatively uneventful and December 1766 found the expedition off the Patagonian coast. Wallis and Robertson were intrigued by myths of the giants of Patagonia and had a chance to investigate further. As the ship stood off Cape Virgin Mary, near the entrance to the Straits of Magellan, the crew saw hundreds of men on horseback riding down the Cape towards the ship.

Heavily armed, in case anything went wrong, Wallis and some of his companions went ashore. The two groups exchanged friendly greetings and gifts, but Wallis had also taken along a measuring rod. The Patagonians were willing to have their height measured. Wallis found that although the tallest was six foot seven, most of the adult men were between five foot ten inches and six foot, with robust physiques.

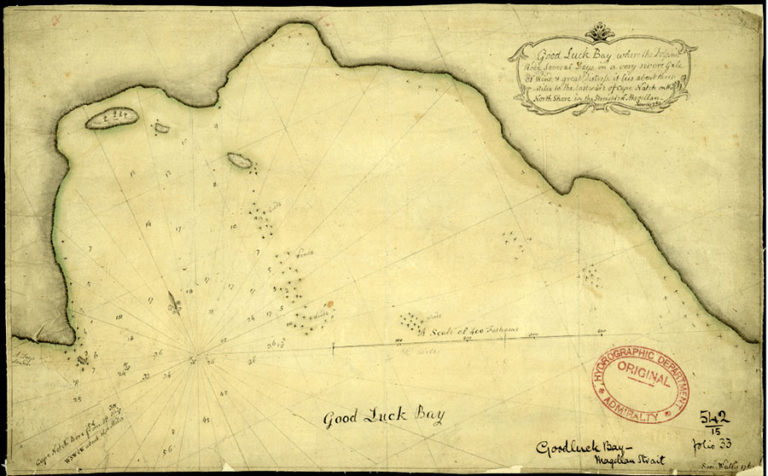

The Dolphin then began the most difficult part of the voyage – navigating the Straits of Magellan. The passage took three months of struggle against north and west gales. Nevertheless, Wallis and his colleagues undertook exploration and surveying, producing a number of charts illustrating hydrology and topography.

By the second week of April, the Dolphin had left the western entrance of the Straits and entered the Pacific. The two ships lost contact and did not meet again during the course of the expedition. By the beginning of June, the crew was desperately in need of fresh provisions and searching for a place to land.

Onshore on Tahiti

On 19 June, the Dolphin’s crew sighted what appeared to be mountains to the south. The officers speculated that this must at last be the southern continent and headed for the nearest land. At daybreak they found themselves confronted by more than 150 canoes – the Dolphin had in fact arrived at the island of Tahiti, which Wallis named King George’s Island.

This initial encounter seemed friendly enough and one of the islanders came on board the Dolphin. However, it became apparent to Wallis that the islanders were suspicious of this intrusion from the sea and were determined to take control of the ship. There followed a week of cat and mouse encounters, which ended in serious violence. The Dolphin’s cannons fired on the Tahitian canoes, destroying several and killing many of their crew.

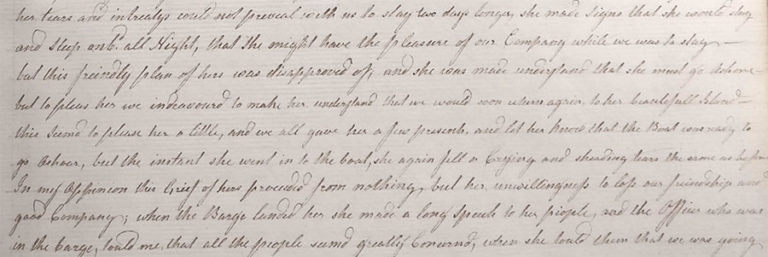

This violence culminated on 26 June, when the Dolphin bombarded a crowd on top of one of the islands hills. These events greatly troubled Robertson, who recorded in his journal that: ‘who terrible must they be shockd to see their nearest and dearest of friends dead, and toar to peces in such a manner as I am certain they neaver beheald before’. (ADM 51/4539, folio 183).

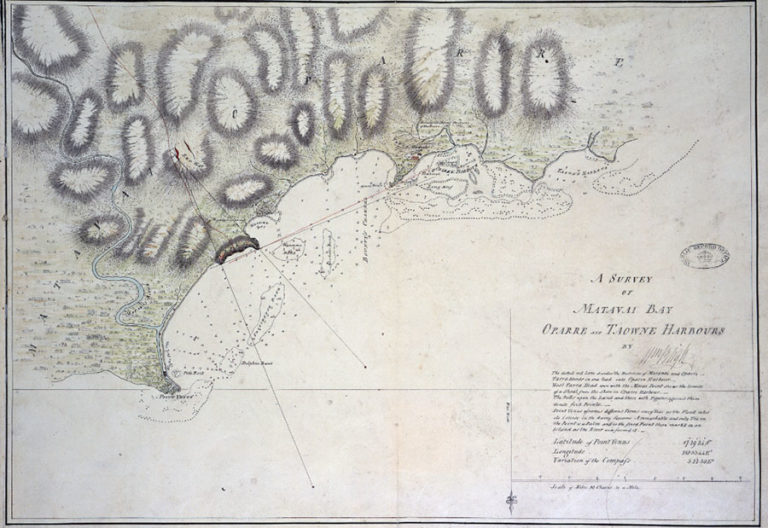

After this, the Dolphin was safely anchored in Matavai Bay and the crew established friendly relations with the islanders. The Dolphin’s stores were soon replenished. The Dolphin’s ‘Liberty Men’ – those allowed shore leave – were soon exploring the island and mixing with the Tahitians, who were very keen to trade for metal, generally in the form of ironware and nails. But a trade in sex was also established.

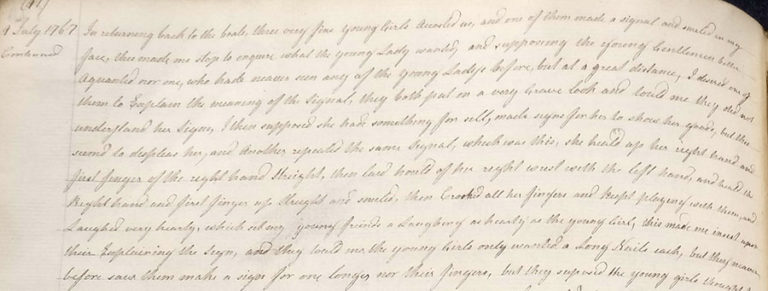

Robertson recorded that he met some young women who made a gesture which he did not understand. Afterwards it was explained to the master that the crew were exchanging ironware for sex. Apart from the removal of metal which threatened the ship, this raised a moral dilemma for the ships officers, who feared that the ‘old trade’ would introduce venereal disease among a healthy population. The ship’s doctor, however, believed that the crew were healthy.

Nevertheless, Cook reported syphilis among the Tahitians when he arrived at the island some years later. He blamed it on the French expedition under Bougainville, which arrived shortly after the Dolphin. It seems very likely, though, that the Dolphin’s crew introduced the disease[ref]H M. Smith, ‘The Introduction of Venereal Disease into Tahiti: A Re-Examination’, Journal of Pacific Studies, 10, 1, (1975), pp. 38-45.[/ref].

Undoubtedly the sailors enjoyed a month on the island. The officers established good relations with the ‘Queen of the Country’, Purea, who was an important chieftain. They attended a feast at her home and she visited the Dolphin, along with her companions. The officers feared that there might be an attempt to seize the ship, but the visit went well with an exchange of gifts and Wallis promised that they would one day return to the island.

The return

The homeward voyage of the Dolphin was relatively uneventful, its route taking the ship across the Pacific through the Gilbert and Ellice Islands and the Marianas, and to the Thames in May 1768.

The Tahitian sojourn has sometimes been portrayed as an idyllic interlude for the crew of the Dolphin, but it also reveals the exploitative nature of colonialism. It was the use of violence, based on superior technology, which forced the indigenous population to accept the newcomers. There was also an exploitative trade and the transfer of disease, which was often devastating for indigenous societies. The logs can only tell us of the naval officers’ perceptions of what happened on Tahiti, and from them we can only infer what the islanders thought of the intrusion.

The poet George Gordon, Lord Byron was the grandson not elder brother of Commodore John “Foul-weather Jack” Byron.

Second paragraph should read May 1766.

Thank you for this. We’ve updated the text now.

The HMS Dolphin under Commodore Byron was a slave ship owned by the crown. There special mission was to force and claim ownership of land with cannons and guns through out the Pacific and New Zealand selling and trading off slaves, human trafficking, children sold into prostitution for and the benefit of Government officials from Police Constables to Resident Agents these are High Court Judges Both NZ and Australian Judges of the Supreme Court from 1765 still documented until 1976.

This man executed an unarmed bound Native, my 7th Great Grandfather on board his ship The HMS Dolphin for removing his black two piece smoking pipe, before murdering raping and pillaging each island, motu he visited. Leaving sexual transmitted diseases, dengue fever the spanish flu, sick slaves from other islands infected with diseases and rot including other unmentionables less not forget Dna evidence.

4 Years later in 1769 The Second White Man showed up and executed another unarmed man a 7th Great Grandfather of the same family and took the land by force now known as Gisborne in New Zealand.

The master of the Dolphin, George Robertson seemed to realize that how the indigenous tahitians were being treated wasn’t proper and spoke of his concerns to other officers only to have his concerns ignored. At least he also logged them into record in the Dolphins voyage log. George Robertson was my 4th great grandfather.