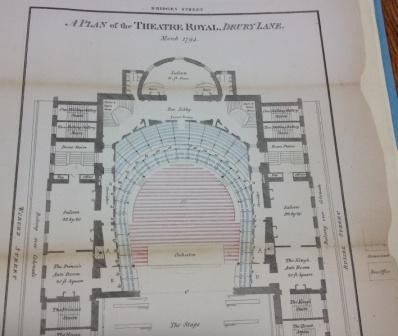

Plan of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 1794 - File ref: MPN 1/25

This coming weekend sees the celebration of London’s West End theatre ‘West End Live‘ which coincides with the 350th anniversary of the Theatre Royal Drury Lane. In 1663, the Theatre Royal opened in London, under the reign of Charles II. The Theatre Royal has had an incredible history of on stage performances which have starred and been attended by many famous people. But did you know about the equally dramatic off stage performance involving the assassination attempt on Mad King George III from a man in the audience in 1800 who also thought that he was King George III?

The records relating to the man in question, James Hadfield, are held here at The National Archives. The papers are from his trial for the assassination attempt on the king, over 200 years ago. They reveal the fascinating story of how James Hadfield went from being a respected officer in the Army to making an assassination attempt on King George III’s life at the Theatre Royal.

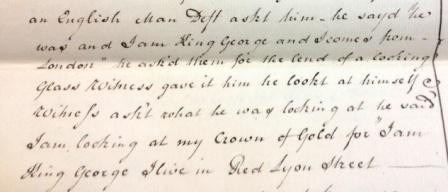

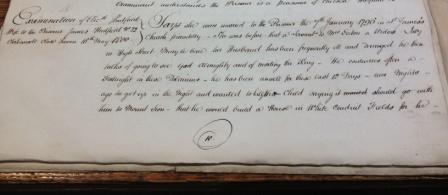

Excerpt from File: Treason- attempted murder of king in Drury Lane Theatre; James Hadfield - File Ref: KB 33/8/3

As well as a map of the Theatre Royal from 1794, the records contain the fascinating testaments of James Hadfield himself, his wife, army colleagues and the many witnesses who were at The Theatre Royal on the night of the attempted shooting.

The Road to Ruin

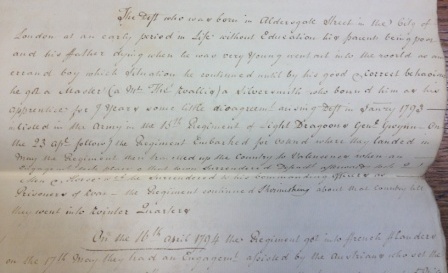

Excerpt from File: Treason- attempted murder of king in Drury Lane Theatre; James Hadfield - File Ref: KB 33/8/3

James Hadfield was a former Army Captain who was fighting in Flanders in the 15th Light Dragoons Regiment. He was an Army Captain of exemplary conduct, according to the records, who was injured through various wounds to the head while in battle in 1794.

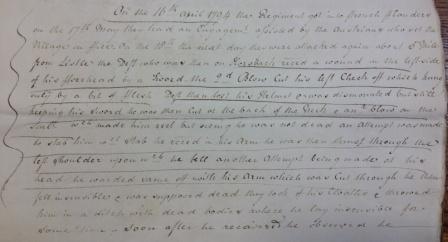

James Hadfield received a blow to the leftside of his head by a sword, followed by a second blow to the left cheek which left his cheek hanging off. After receiving a couple more blows to the head and arm, forcing him off his horse, he was thrown into a ditch in the battlefield where he was then left for dead. Two French officers found him alive and they took him to a house full of dead bodies. The next day he was given milk and water before having to walk to the wagon, holding the cheek that was hanging off his face, which would transfer him to a hospital where he received treatment for his wounds.

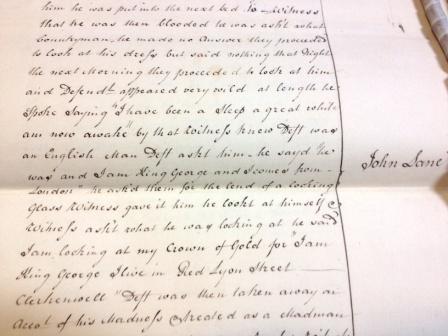

Excerpt from File: Treason- attempted murder of king in Drury Lane Theatre; James Hadfield - File Ref: KB 33/8/3

A witness, John Lane, who was in the bed next to him in the hospital, gave a character reference in which he tells of James’ belief that he was ‘King George’ and other details of his ‘damaged state of mind’ which resulted in John Lane requesting that James Hadfield to be moved to another part of the hospital.

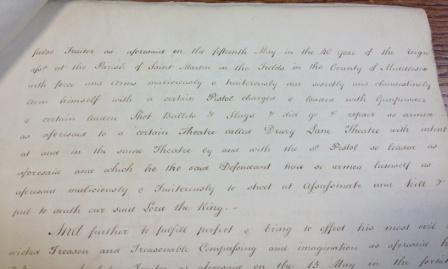

Excerpt from File: Treason- attempted murder of king in Drury Lane Theatre; James Hadfield - File Ref: KB 33/8/3

In other witness accounts, after James Hatfield received more wounds from prisons and escaped, he found a lake where he could bathe his wounds, he claimed he was in heaven and that he was Adam [the biblical character] and made himself a ‘covering of boughs of trees’ to put round his waist.

He was taken to prison again after that where he smashed a water jug and proceeded to cut his feet with it to ‘purge away his sins’ whilst claiming he was the ‘Supreme Being’. After some time, he got well again and escaped to Calais, where he then took a boat to Dover, arriving in London in September 1795.

He rejoined the regiment, arriving in Croydon Barracks on 5 April 1796 and was discharged soon after due to insanity and was collected by his brother. He eventually found work as a silversmith and four years later, after several ‘fits of insanity’ including one where he threatened to dash his child’s brains out (just days before), he made the assassination attempt on Mad King George.

Excerpt from File: Treason- attempted murder of king in Drury Lane Theatre; James Hadfield - File Ref: KB 33/8/3

On 15 May 1800, James Hadfield made his way to the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, knowing King George III was attending. He entered into the pit by the orchestra, drew out his pistol and aimed it at the King who was seated in the King’s Box, narrowly missing him.

Excerpt from File: Treason- attempted murder of king in Drury Lane Theatre; James Hadfield - File Ref: KB 33/8/3

James Hadfield was put on trial for high treason but was acquitted on the grounds of insanity.

Madness in the Spotlight

The case of James Hadfield put legislation on high treason and the custody of insane people into the spotlight. As a result, James Hadfield was a major catalyst in establishing the Criminal Lunatics Act 1800 and Treason Act 1800 which were reportedly proposed by the prosecution no more than four days after the trial. He also indirectly influenced the opening of Bedlam (later known as Bethlem) Hospital to detain lunatics.

If you would like to find out more about James Hadfield and his custody following his acquittal, you can find his records in the recently digitised historical criminal records which date from 1817-1931.

Rebecca,

I would also add that there are records in TS (Treasury Solicitor’s Department) files (which are not in the list of digitised records, for some reason) and that King George III had a stone thrown at him by a man called Frith in the 1790s who claimed to be Saint Paul and the case of Hadfield sounds rather like the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. In later years Broadmoor was set up following numerous attempts on the life of Queen Victoria, although it is now treated as being a hospital rather than a prison.

David