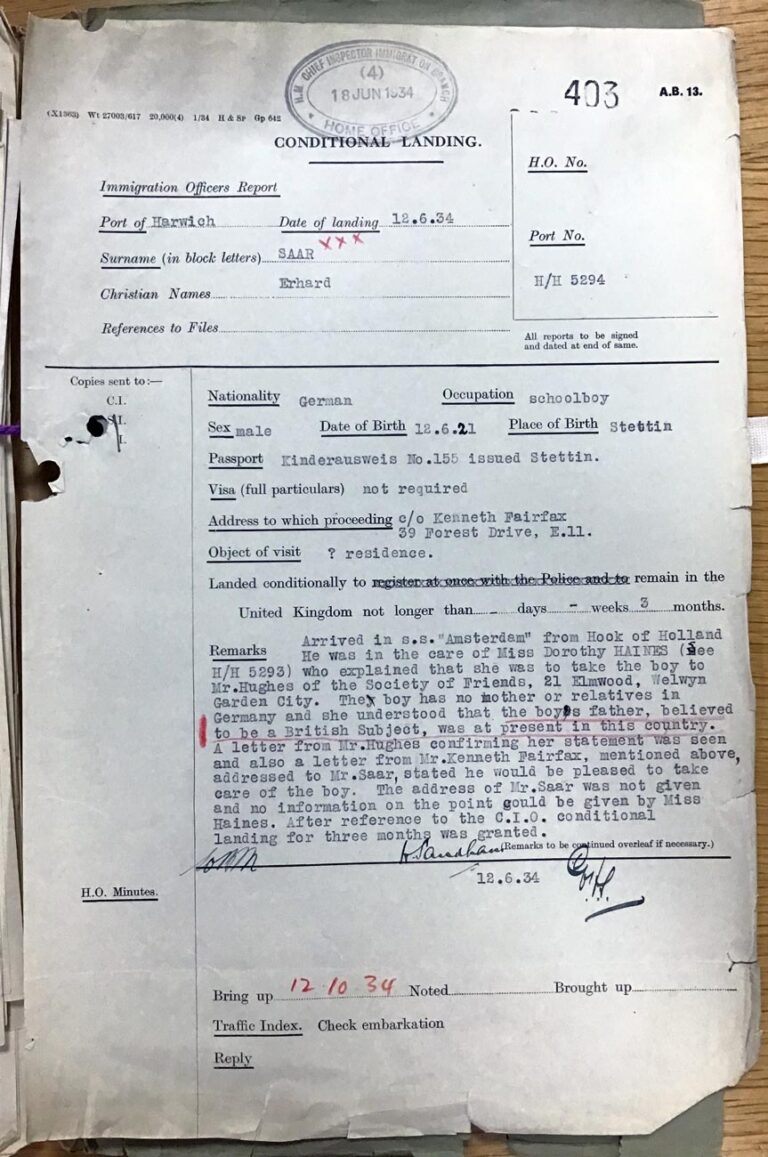

On 12 June 1934, 13-year-old Erhard Wilhelm Saar landed at the Port of Harwich on the S.S. Amsterdam, accompanied by a Miss Dorothy Haines. She explained to the British authorities that she was to take the boy to the Society of Friends in Welwyn Garden City, where he would be housed with a Jewish family in Manchester and attend one of the local schools.

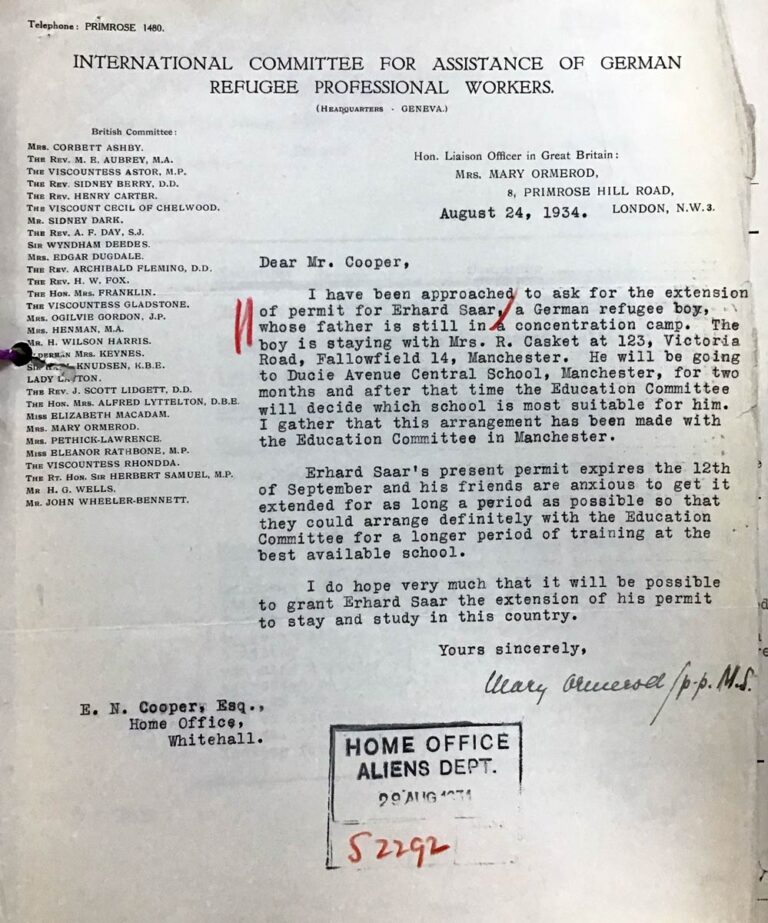

Erhard, also from a Jewish family, was from Stettin, which at the time was in Germany (now Szczecin in Poland) and had been sent to the United Kingdom by his father for his safety for an initial three months. A letter dated August 1934 in his Naturalisation papers, held at The National Archives, sent to the Home Office from the International Committee for Assistance of German Refugee Professional Workers requesting for his permit to stay in the UK be extended, also stated that his father was being held in a concentration camp. A former soldier, Erhard’s father, having moved his family to Berlin, had become an active anti-Nazi activist in the Communist Party and was soon persecuted for his activities.

Moving to Manchester

The young Erhard was initially sent to Manchester Grammar School which, after a further request to the Home Office, permitted the extension of his permit to remain in the UK until 1936. After various other extensions, requested by the Society of Friends Germany Emergency Committee on behalf of Mr and Mrs Lees, the family with whom he was living, Erhard was finally granted the right to remain in the UK until 31 August 1939 – as it turned out, three days before the British declaration of war on Germany.

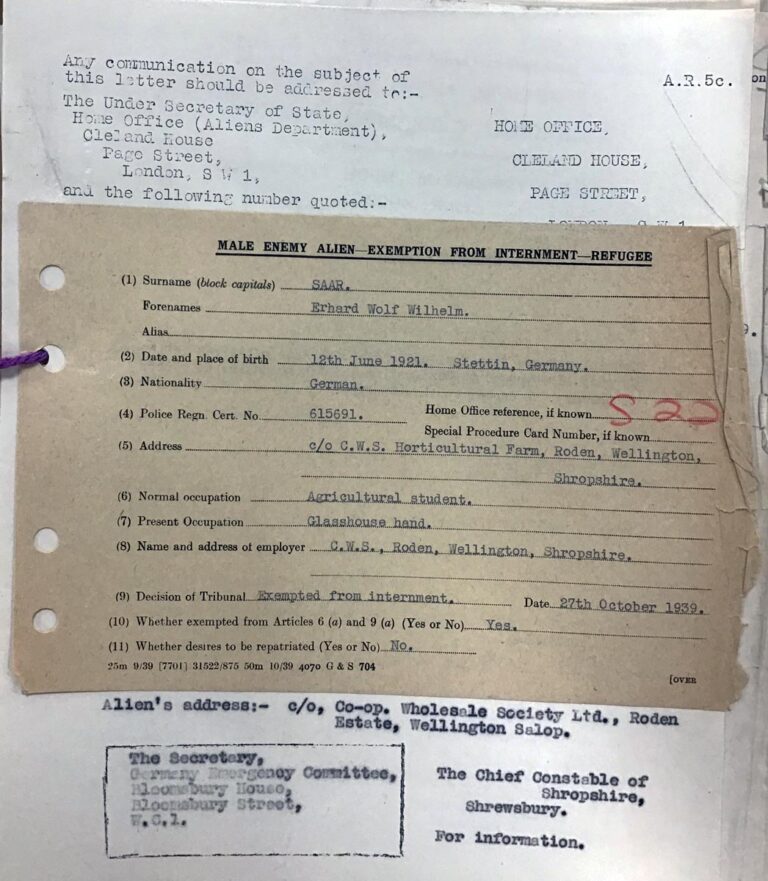

By this time, he was training in horticulture and employed as a glasshouse hand at the Co-operative Wholesale Society and had opted to change his name to Edward Lees, taking the surname of the family which had taken him in. In the application made for permission to allow him to work (‘aliens’ were only permitted to carry out certain jobs), it was stated that:

‘This youth is a refugee from Germany who has now little or no means of support. The post is offered, therefore, primarily from charitable reasons but it may be added that difficulties have been experienced in obtaining suitable young workers of British nationality for work of this kind’

The threat of internment

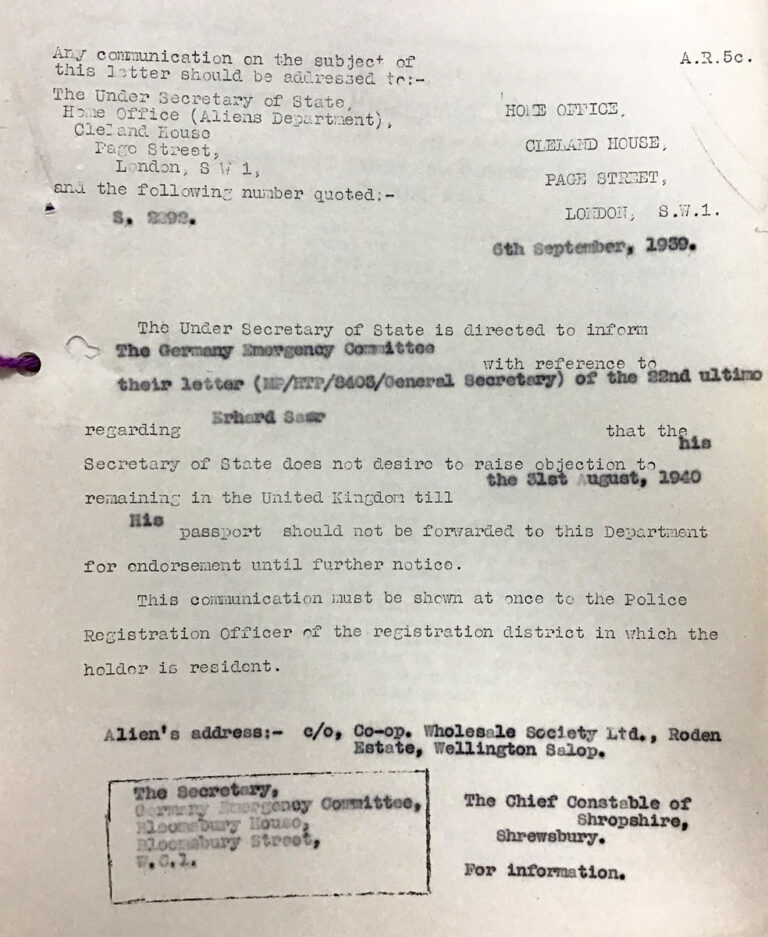

Despite war with Germany, Edward was informed on 6 September 1939 that, once again, he was only permitted to remain in the UK for another 12 months.

At the outbreak of war, the British Government had undertaken to intern those from enemy countries who it felt might be a security risk. Individuals were required to attend a tribunal which decided whether someone would be exempt from this. On 27 October 1939, the local tribunal ruled that Edward would be exempt from internment due to his status as a refugee. The proof of his exemption noted the following:

‘Genuine refugee from Nazi oppression. No near relatives left in Germany. Is opposed to Nazi regime and has no desire to return to Germany. No danger to this Country.’

Joining the British Army

By the early summer of 1940, with the war not going in the Allies favour, the decision was made to intern all enemy ‘aliens’ and Edward did not escape this fate. He was interned in Liverpool over that summer for a period of six weeks. Along with all other male internees of the right age, he was given the option to join a non-combatant corps of the armed forces in order to support the war effort. Edward jumped at this opportunity, was freed, and enlisted in the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps on 23 September 1940.

By 1943, after long periods of training in the UK, Edward was transferred to the Royal Fusiliers, where he was then recruited by Special Operations Executive (SOE), the organisation responsible for carrying out covert operations behind enemy lines.

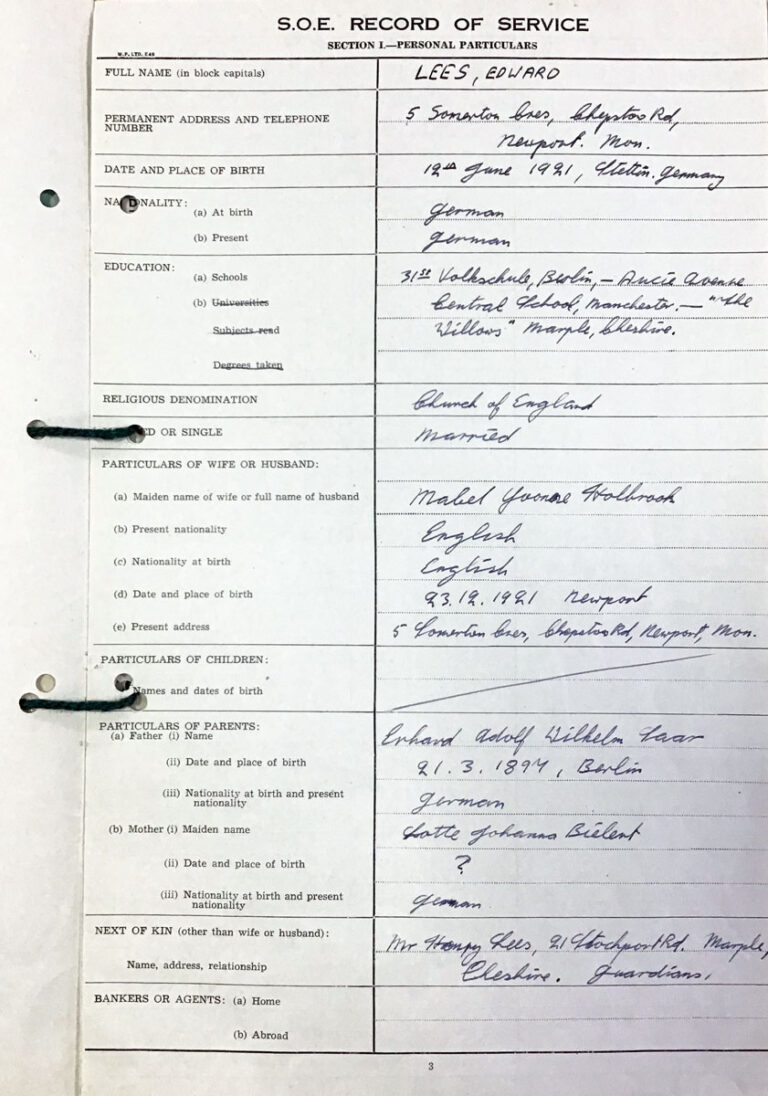

Information in Edward’s SOE service record, held by The National Archives, provides us with an insight into his service and personality. His instructors consistently described him as quiet and focussed on his job, always willing to learn. Interestingly, his religious denomination was listed as ‘Church of England’ rather than as Jewish. It was noted that he was fluent in German and had a working knowledge of Italian.

These language skills must have influenced where he would be sent. In August 1944, Edward was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and sent overseas. Specifically, he was tasked with parachuting behind enemy lines in northern Italy, where he gained a formidable reputation as a demolition’s expert, working with local partisans seeking to hamper the Axis retreat. He was given the cover name Edward Chaney, something which was often done in order to protect the identities of Jewish soldiers working in Nazi occupied territory.

After the war

Edward remained in Italy until the end of the war in Europe and, continuing his work in the British Army, was swiftly transferred to Special Camp 11 in South Wales , which had become a prisoner of war camp for senior Nazi officers awaiting war crimes trials. Here, he was promoted to Captain, acted as the camp interpreter, and reportedly got on well with many of the prisoners.

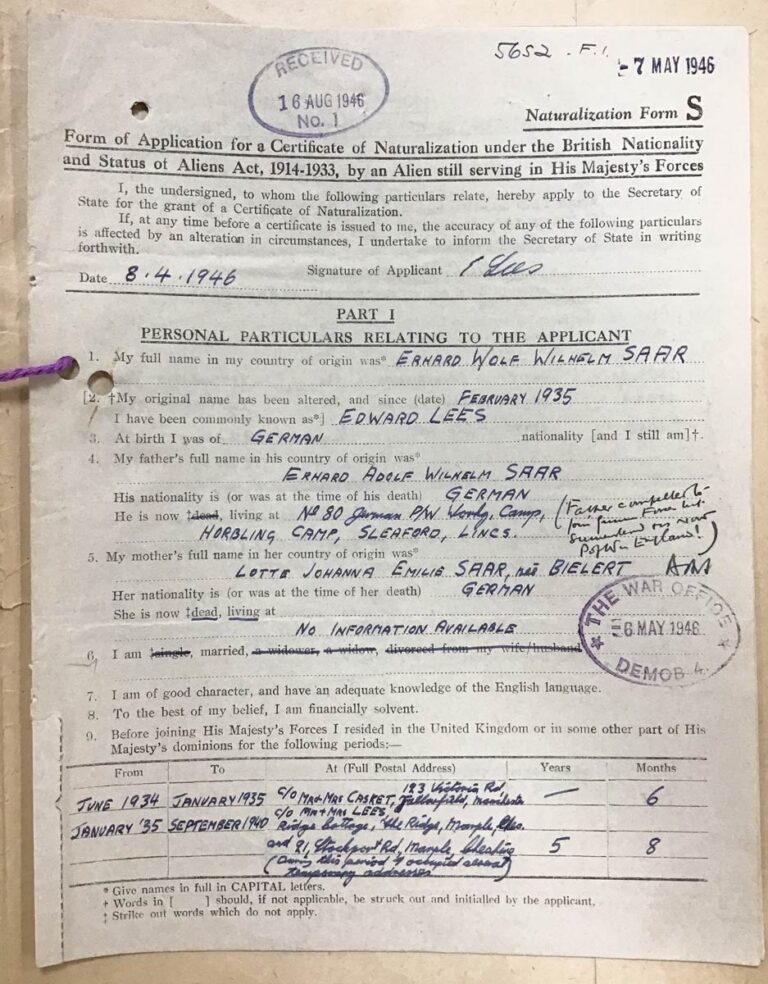

In 1946, Edward was finally able to naturalise as a British citizen, having already married Mabel Holbrook in 1942. Remarkably, on Edward’s Certificate of Naturalisation, where his father’s information is recorded, it is stated that, despite his age (he was nearly 50), his father had been compelled to join the German Army, and at that time was being held in No.80 Prisoner of War Camp in Sleaford, Lincolnshire.

Edward (known by friends and family as Ted) continued living in South Wales and, after leaving the army in 1948, went on to have a distinguished career in the Glamorgan Fire Service, while also acting as the official German interpreter for Glamorgan County Council. Edward died in 1985 at the age of 64, having never returned to his country of birth.

Find out more

Find out more about Second World War internment and POW records at our free exhibition Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives. Opening Friday 2 February 2024, Great Escapes explores the human spirit of hope and resilience during times of captivity, revealing both iconic and under-told stories of prisoners of war and civilian internees during the Second World War.

We’ve also scheduled a season of special events to accompany the exhibition that are available to book now.

What an incredible transition from internee to non-combatant to combatant to officer in the SOE! I wonder how many went through such a path.

We need to remember heroes like Edward (Ted) reading stories like this puts these guys on a pedestal never ever to be forgotten

Wonderful story of a jewish boy saved from nazism. Would be nice to know if he was reunited with his father and moher.

As I read this story, I wondered would he survive the war or would he be captured and severely ill treated.

I do hope that his father was able to live a reasonably comfortable life after the war and was allowed reunite with Edward. I hope also that his mother was found.

One would assume he met at least his father, if he was in POW camp in Lincolnshire in 1946.

We aren’t sure, but they almost certainly must have been in contact with one another for Edward to know in which camp his father was being held.

This is an amazing story, what difficult times. His father managed to get him out of the country, what difficulty there was being a refugee even during the war! Luckily he was able to show his usefulness and ingenuity, perhaps this was not the case for everyone sadly. I would like to know if you have the prisoner of war record of his father and what happened to him after the war. Is there any records of his mother and if she survived?

POW records created by the British authorities on German POWs were returned to Germany after the war (as was a condition set out by the Geneva Convention) and are available from the Bundesarchiv. The National Archives does hold some administrative records relating to the camp in which his father was held (as well as for other POW Camps in the UK). If any records for his mother survive then they would most likely be held in Germany.

I am just reading this statement “given the option to join a non-combatant corps of the armed forces in order to support the war effort“ and wonder if anyone knows if there are records pertaining to this? I realize if an internee said yes there will be military records but are there records of those who declined or perhaps were never asked?

Those who declined where, at least initially, kept in internment camps. The National Archives holds many records to do with the administration around internees joining the armed forces, alongside a detailed collection of interment cards in HO 396 (which have been digitised). More information can be found in our Internees research guide.

AMAZING

This is only part of his life.

I find now much more information submitted by his daughter.. Bravo

http://www.islandfarm.wales gives much much more about POW Camp 198 in Bridgend

So sad that he died young in 1985 from a heart attack.

Hopefully these documents plus those that I found today can be given wider circulation.

Whilst my parents were also refugees from Nazi oppression reaching UK in 1938/1939, also with some help from Quakers , and interned or doing domestic servant / war work, they settled quietly into civilian life unlike Edward Lee from Stettin. bravo

This is so interesting. Might be nice to make his life story into a film.