On Monday I visited the beautiful Phoenix cinema and saw the new Ken Loach documentary The Spirit of ’45. Loach depicts the period immediately following the Second World War when a series of welfare reforms – including the establishment of the National Health Service – and the nationalisations of certain industries reshaped British society, as the country attempted to recover from six years of war.

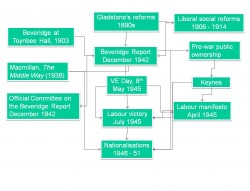

A representation of the genesis of the Beveridge Report and Labour's reforms

By using personal recollections from those who remember the period – and of the country before the welfare reforms – Loach shows how a generation was defined and delighted by reforms that formed a social safety net for everyone in Britain. In what is often seen as a revolution of sorts, everyone in the country was suddenly – in some sense – provided for by the state. If they fell ill, they could be treated, if they lost their job, they could survive and continue feed their children. The nationalisations, the National Health Service, the national insurance contributions which paid for social security created what many saw as a new Britain that would never again see care and wellbeing go to only those who could afford it.

The welfare reforms instituted by Clement Attlee’s Labour government of 1945-51 have their genesis in the Beveridge Report, first published in December 1942. 600,000 copies of The Report on Social Insurance and Allied Services were sold and it has long been held up as a symbol for post-war society, detailing how the ‘five evil giants’ of Squalor, Ignorance, Want, Idleness, and Disease would be challenged and defeated. However, the covering note of the War Cabinet memorandum which provides the original terms of reference of the report (CAB 66/31) carries the line that in some ways it was a ‘revolution’, but in Beveridge’s own words, ‘in more important ways it is a natural development from the past.’

There are several reasons for why this can be argued. Many benefits existed before and during the war and Beveridge was tasked to bring these together, in order to simplify their administration. He writes in his report that, ‘the provision for most of the many varieties of need through interruption of earnings and other causes that may arise in modern industrial communities has already been made in Britain on a scale not surpassed and hardly rivalled in any other country in the world.’

Beveridge, as a liberal, was influenced by Gladstone’s reforms of the 1890s and was already an expert in unemployment insurance by the time of the Liberal social reforms of 1906-14. The terms of reference for the report – ‘the report is the report of Beveridge’ – gave him the freedom to elaborate on his own terms and he married this with the aim to bring together existing social security schemes in order to explain his designs for a social safety net for all: ‘the security of an income to take the place of earnings when they are interrupted by unemployment, sickness or accident, to provide for retirement through age, to provide against loss of support by the death of another person, and to meet exceptional expenditures, such as those connected with birth, death and marriage.’.

Even the nationalisations of the post-war Labour government were not completely divorced from the Britain prior to 1939. The BBC, the Central Electricity Board, and the British Overseas Airways Corporation were all brought under public ownership in the 1920s and 1930s. Even Harold Macmillan, the future Conservative prime minister wrote in 1938 of the need to certain industries to be nationalised.[ref] 1. In The Middle Way. David Kynaston describes Macmillan’s programme as ‘at least as ambitious as that then being advocated by Labour. Kynaston, David, Austerity Britain, 1945-51. [/ref]

Certain elements, however, seem to suggest that the 1940s allowed for uniquely fertile terrain for the implementation of wide social reforms. Beveridge called for three assumptions that were necessary for the implementation of his scheme – children’s allowances, comprehensive health and rehabilitation services, and full employment. These were to be paid by taxation, and the usually conservative Treasury may not have obliged had it not already hired John Maynard Keynes as an economic adviser. His papers (T 247) show us how he strived to impress upon his colleagues the requirement for as high a level of employment as possible, and flexible rates of taxation depending on the relative buoyancy of the economy.

The Labour manifesto, published in April 1945, expressed these ideas in a way that appealed to the public so strongly that the party won a landslide victory in July’s election. The ‘Appointed Day’ of 5 July 1948 – when much of the social security legislation began to apply and the NHS came into being – saw a marked change in the state’s provision for it’s people. It seems difficult to imagine that Attlee’s government would have been able to implement such changes were it not for the work of the likes of Beveridge and Keynes during the war years.

The Beveridge Report caused serious concerns for the Treasury and it became apparent that the new system of family allowances was not achievable leading to the decision that Family Allowances (the forerunner of Child Benefit) would not be paid for the first child. It should not be forgotten how the consultants in Britain’s health services tried to oppose the National Health Service and even up to almost the ‘Appointed Day’ fought against the proposals. The old system whereby people were afraid to go to the doctor because they could not afford the cost was swept away.

The work of Keynes also raised serious concerns that he was agreeing to proposals of the loans from the United States and that he was agreeing to proposals without approval from the Cabinet and the Treasury’s Permanent Secretary Edward Bridges had to go and try to rein Keynes in. Keynes had also served in the Treasury during the First World War and suddenly resigned on the eve of the Versailles Peace Treaty in 1919 over German reparations which he correctly stated that this was the wrong decision and would lead to problems and the World had the Wall Street Crash, unemployment and the Second World War.

Nationalisation was costly but necessary as most of the industries were on the verge of collapse. Unfortunately the NHS was subject and still is to the politicians who have tried to reform the NHS and the tiers of administration of 1974 is certainly a case where it failed.

Thanks for your comments, David.

I quite agree, these are subjects that can be investigated far more deeply – certainly the BMA’s opposition to the installation of a national health service, and Aneurin Bevan’s negotiations with the body is of interest.

Keynes’ influence over Western politics from the 1930s to 1970s, roughly, is fascinating – The New Deal and the nationalisations of industry significantly altered the US and UK economies, even if the subsequent influence of free market economics and monetarism in those respective governments suggests such state intervention could just have been a historical blip.

Simon