The origins of the earliest architectural drawing in The National Archives are shrouded in mystery. This plan of a church was found among Exchequer miscellaneous accounts and expenses, such as a bill for jewellery. There is no writing on the plan and no indication which church it might show. This blog records attempts to find out more about it.

The Sheriff aka The Merchant

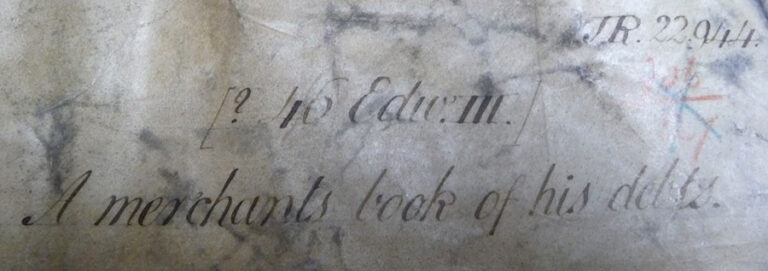

The plan is now folio 4 of a volume containing a notebook listing debts due to a 14th century London merchant (see footnote 1). The cover has a title added in a later hand.

This has been identified as the account book for 4 July 1390 to 23 June 1395 of Gilbert Maghfeld (footnote 2). A notable of his time, Maghfeld or Manfelde was Sheriff of London from 1391 to 1393, and before that was variously an ironmonger, a credit broker, moneylender, and perhaps the basis for Chaucer’s satirical pen portrait of The Merchant (footnote 3).

Chaucer and a debt

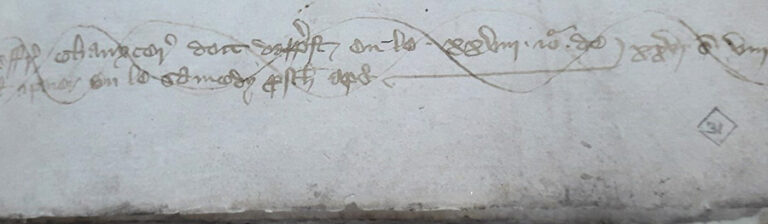

Chaucer moved in the same circles as Gilbert Maghfeld, and the merchant’s notebook furnishes a concrete connection between them. On 28 July 1392 Chaucer took out a loan of 26 shillings and 8 pence from Maghfeld, an amount worth nearly £900 today. The line through this entry shows that the loan was repaid, presumably within the week. The reason for the loan is not given, and Chaucer appears to have requested it just after receiving a large amount of £13 6 shillings and 8 pence (nearly £9,000 today), part of the sum owing to him as outgoing Clerk of the King’s Works (footnote 4).

The Nave, and the rest of the church, too

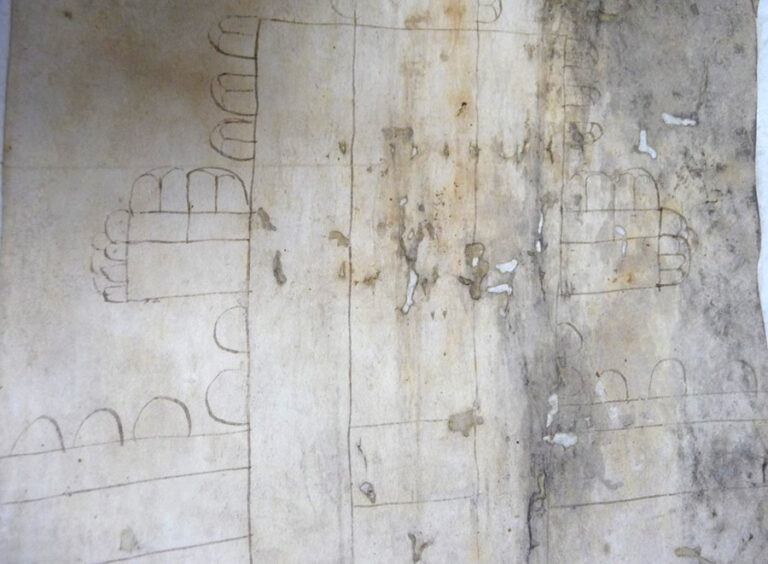

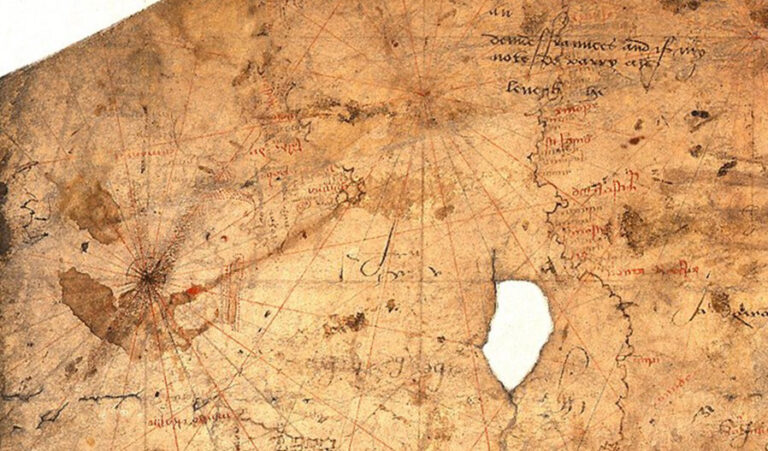

The plan is now bound in to the front of the merchant’s notebook, but it is not clear that it is related to Gilbert Maghfeld, or to Chaucer. It is drawn in pen and ink on parchment, roughly 26 cm high and 17 cm wide, which has at some point been pasted on a larger sheet of parchment, ‘upside down’ to our eyes, i.e. with the chancel at the lower edge. There is nothing written on the plan (or the dorse) to say which place it shows, when it was drawn, or who drew it and why.

The outline sketch plan shows a large monastic or cathedral church, with chancel, transepts and aisles, perhaps a central tower, two side chapels of some size with markings on the plan which may indicate further chapels or tombs within them, and a Lady Chapel. On the outside of the north-west wall of the church are drawn diagonal parallel lines. What might these mystery marks represent? One possibility is that the church joined another structure at this point, with extant or projected buildings to one side.

The length of the church appears at least 3.5 times the width of the nave and about 1.5 times the width including transepts. However, the ends of the transepts and the west end are not shown; the pen lines stop at the edge of the page, so it is possible that they were originally completed but these parts lost (perhaps cut to fit the notebook); although the irregular-shaped edges of the parchment suggest that what we see may be what was originally drawn. Perhaps these areas were not important for the purpose for which the plan was made. We need, then, to imagine a church extending further than is shown on the plan.

Simple in general style, the plan bears more detail of some windows around the chancel and transepts. The chapels and windows are drawn ‘on their backs’, as if they are laid flat on the ground, which was probably an attempt to show that the chapels projected from the body of the church, and that the windows had some tracery.

Which church might the plan show?

With any plan, there is a question of whether it shows a building in design, as built, or additions and changes made at a later date. This plan seems too detailed to be a design, so seems likely to represent a real church at some point in its evolution. There is an item in Gilbert Maghfeld’s list of debts which mentions wages for paving and wainscoting at St Antonin’s church in east London, but that is a much smaller church than is shown on the plan.

An expert view

I approached the architectural historian Dr Steven Brindle who was most interested to hear about the plan, since, as he said, ‘Contemporary plans or drawings of medieval buildings are as rare as hens’ teeth, so this is an exciting object’. There is no doubt that it represents a cathedral-sized church, he notes, and English in design. The presence of an eastern transept limits the possibilities, as does the depiction of what may be buttresses on one side, suggesting that there was to be a cloister on the other, Dr Brindle observes; this suggests that this represents a monastic cathedral, something peculiar to England. Salisbury Cathedral most closely resembles the plan, but differs in quite a number of details.

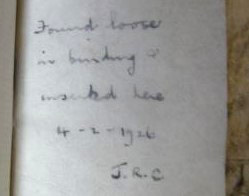

In a bind

In the left margin of the larger parchment sheet to which the plan is affixed is written in pen and ink a note dated 1926: ‘Found loose in binding and inserted here … J.R.C’. Two other sheets of text also bear this note, on paper, in a sorry state; these appear to be related to previous business of Gilbert Maghfeld, perhaps brought forward from an earlier notebook. Within the notebook three other items bear the same note in the same hand, without the reference to the binding; two of these are on parchment, like the plan, but appear to be a note of accounts similar to those on paper in the notebook (footnote 5).

The date of 1926 links with Edith Rickert’s story that Hubert Hall, a retired Deputy Keeper of the Public Record Office (footnote 6), already knew of the notebook but invited her to see it (see footnote 2). It would appear likely that ‘J.R.C’ was an editor undertaking a sorting exercise, perhaps linked to the American academic’s visit in 1926, around which time a number of changes were made to its makeup. It is just possible that ‘J.R.C’ was an early conservator, but staff records in our Collection Care department do not go back far enough to confirm this idea.

Material evidence

Current conservators Sonja Schwoll and Giorgia Genco examined the notebook and their findings suggest that it was rebound about the same time as the pages were inserted in 1926, using the original parchment cover as was in fashion at that date, but with new stitching – darker areas in a different place on the cover suggest where the earlier stitching lay. There are currently two text blocks within the cover: the notebook is in the second half, while the formerly loose pages are at the front along with the notebook’s original paper back cover, as matching wormholes attest.

Sonja and Giorgia noted a correspondence between holes in the church plan and the first blank leaf, not related to insect damage. They thought that this could be related to some previous means of attachment, either along the spine or on the cover, but it was difficult to come to any firm conclusions. The material evidence, then, yields few clues that would take forward the story of the plan’s origin and what happened to it.

Loose leaves: questions remain

Were the plan and two pages that are also ‘found in the binding’, as per the 1926 notes, really connected with the account book? If the plan was bound into the volume in 1926, along with other loose pages, it was thought at that date most likely to be associated with it. However, the plan is the only item on parchment in the volume, apart from two small slips with notes of accounts, also inserted in 1926, later in the notebook, where they had been found. This suggests that those slips had been used as markers to quickly re-find a page.

The plan would ostensibly appear to be much earlier in date than the notebook, with no obvious link to Maghfield or his business. Might it have been used as a bookmark, too? Perhaps it was found loose as a separate item within Exchequer miscellaneous accounts and expenses. Or was the plan perhaps used as scrap parchment to pad the volume’s binding, despite the absence of heavy creasing that would be expected if this was the case? We know this kind of repurpose happened; our 14th century portolan chart was reused to cover a Tudor account book (and so has been known for the last 60 years since that discovery as our oldest map-related item – perhaps this plan now takes that title) (footnote 7).

If the plan was not originally part of the account book, when a dating in the latter 14th century might be inferred, its date is another wide open question, unless it can be related to a specific site, and perhaps to dated building work there. There is a scarcity of original early English church plans with which to compare this and perhaps date it approximately by the style of plan (footnote 8).

There is much about this medieval church plan that remains a mystery, such as why such an item is among the Exchequer records. Those documents which have found their way to the ‘miscellaneous’ category without definite provenance can be very hard to research. I hope to have drawn attention to the plan, so that others may perhaps now be able to place it within the annals of early architectural and ecclesiastical history.

Footnotes

- E 101/509/19: the online catalogue description dates the accounts therein between 1371 and 1395. This is the dexter (stamped) folio 4 presumably added when the volume was reformatted in 1926; the merchant’s account book contained later within the volume has an original numbering sequence, in French. This image is rotated 90 degrees to the right from the way the plan is bound in to the notebook.

- The first appraisal in print of this notebook, with partial listing of contents, and with an emphasis on its interest for social history, was an article Extracts from a 14th-century account book by E Rickert in Modern Philology, Volume XXIV, 1926-1927 pp. 111-119. Mercantile aspects of the notebook were discussed in A London Merchant of the Fourteenth Century by Margery K James, in the Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 8, No. 3 (1956), pp. 364-376.

- This is likely to be the Gilbert Manfeld, citizen of London, who is noted as a creditor for debts in cases that came before the Court of Chancery in 1386: records in C 131/205/5 and C 131/28/23. For more on the account book, see article The Account Book and the Treasure: Gilbert Maghfeld’s Textual Economy and the Poetics of Mercantile Accounting in Ricardian Literature, Andrew Galloway, Studies in the Age of Chaucer, The New Chaucer Society, Volume 33, 2011, pp. 65-124.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Geoffrey Chaucer accessed 8 November 2022.

- At folios 20 and 36.

- A precursor of The National Archives.

- For the full story of this chart see Maps their untold stories: map treasures from The National Archives, Rose Mitchell and Andrew Janes, Bloomsbury, 2014, p.138 with illustration on p.139.

- There is nothing similar among the few ecclesiastical plans shown in Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England, R A Skelton and P D A Harvey (Eds.). Oxford University Press, Oxford (1986).

What a puzzle! Thank you for publishing- so interesting. I would love to think you will be able to identify the church / cathedral.

I deliberately pondered the plan before I read the blog (so as not to have my judgement influenced by what might follow), and quickly concluded that it represents Salisbury Cathedral; then I saw that Steven Brindle had compared it to Salisbury.

Allowing for the fact that the appendages are not shown (treasury, N porch and cloister), everything else fits Salisbury: continuous N & S aisles throughout the nave and eastern arm; buttress spacing on the N side of the nave indicates its 10 bays; single-aisled N & S main transepts of 3 bays with a window in each; single-aisled eastern transepts of 2 bays with 2-light windows on the E, and 3 lights on N & S, plus a chapel window; 2 aisle bays with windows between the transepts on N & S; 4 aisle bays with C13, 2-light traceried windows E of the transepts (but only 3 shown on plan, the 4th being omitted because of overlap with the E transept window); projecting Lady Chapel of 2 bays, each with 2-light traceried windows.

The omissions from the plan may help to date it. The cathedral was begun in 1220; the treasury was added c.1240-50 and the cloister not finished until c.1265. The absence of the west front and towers could be attributable to cropping the plan, or they may not have been completed when it was drawn. The latter reason could also apply to the omission of the N porch. I tentatively suggest that the plan dates from the mid-13th century, and shows Salisbury Cathedral nearing completion.