‘If we could have seen any other course open we should have taken it.’

Sam March (Mayor), speaking on behalf of the Poplar Borough Council from Brixton Prison, 20 September 1921[ref]HO 45/11233, The National Archives.[/ref]

In 1921, 30 councillors and guardians were sent to prison for defying the government. But why?

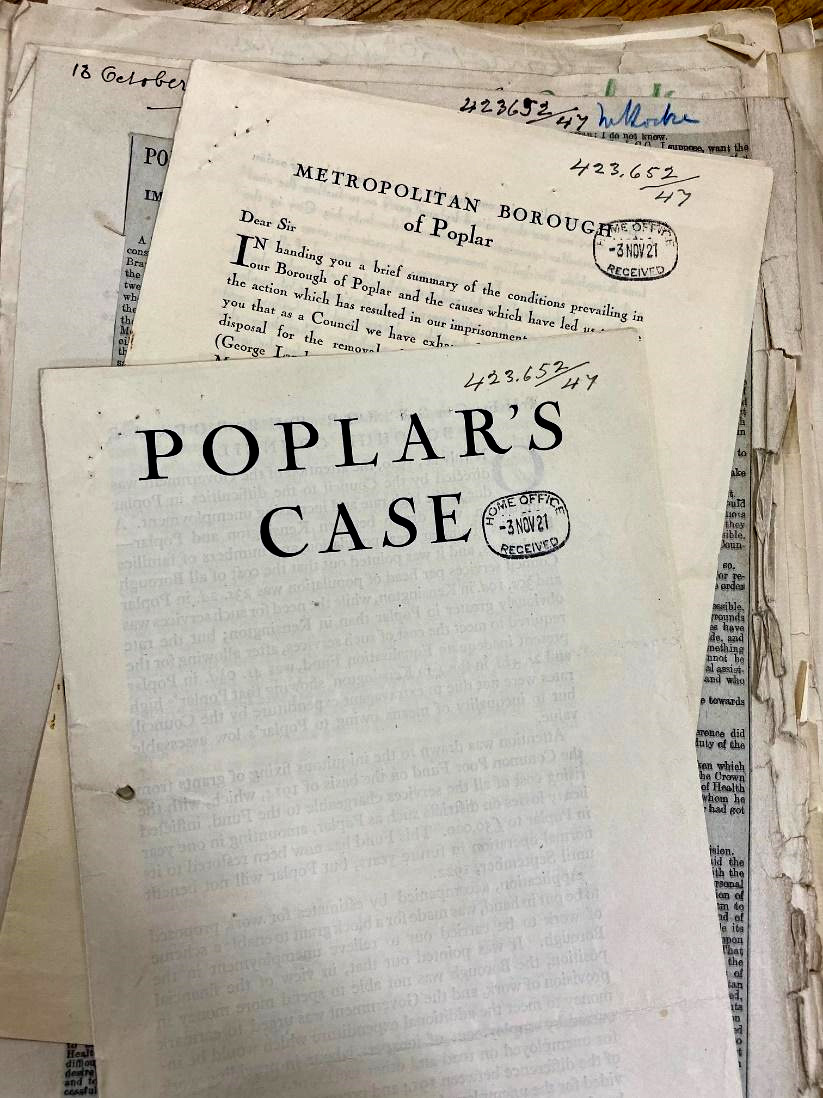

In this blog, I will explore this unique moment in English political history and reflect on what records held at The National Archives can tell us about this extraordinary case.

1920s Poplar

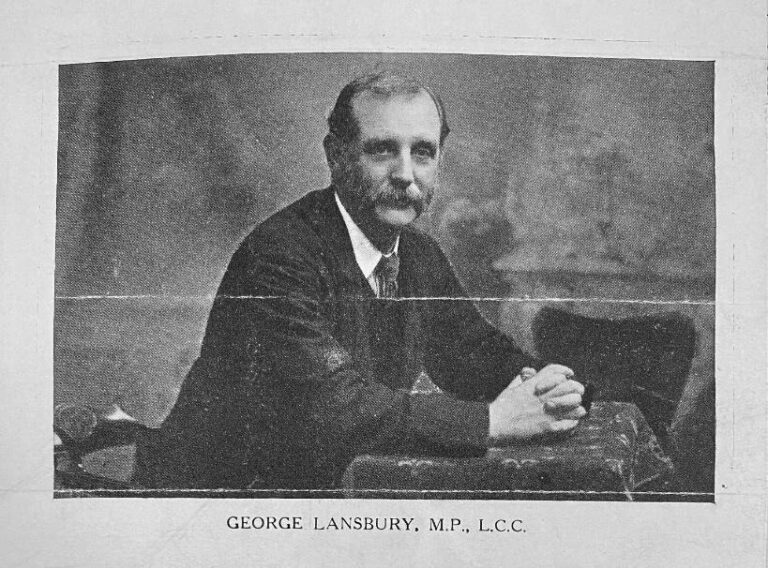

In the early 20th century, Poplar, East London had very high levels of poverty, overcrowding and unemployment. In 1919, Poplar Borough Council’s Labour administration had been elected on a socialist mandate to bring about much-needed change to the borough. Those elected included Jane March, a former health visitor, Jennie Mackay, the first woman member of what would become the National Union of General Municipal Workers (forerunner of the GMB union), and several suffrage activists including George Lansbury, Nellie Cressall and Julia Scurr. In 1912, Lansbury had even resigned his seat to force a by-election on this issue of women’s suffrage.

Despite the dire need, money to support residents in the borough was tight, and the council was faced with the prospect of a further large increase in the rates from central government. These rates went to pay for centralised services such as the Metropolitan Police, Metropolitan Asylums Board and the Metropolitan Water Board. Poplar desperately needed money for poverty relief and unemployment support, and yet Poplar rates raised significantly less than more wealthy boroughs because of the lower rateable value of properties. It was a tricky situation. The council did not feel it could support the needs of its citizens and pay the central rates.

In response, the council came up with a novel plan. The idea was simple, but revolutionary: to only raise the rates for the expenses of the Poplar Council itself and to refuse to pay the central rates. On 22 March, the action was voted on and the resolution was passed (MEPO 5/97).

As Sam March, Poplar’s Mayor, wrote in a leaflet entitled ‘Metropolitan Borough of Poplar’:

‘Briefly, then, our demands are for the complete equalization of the rates of London for all services throughout the County of London, and provision out of National Funds of work or maintenance for unemployed throughout the land.’

On behalf of the Poplar Borough Council, Sam March (Mayor), Brixton Prison, 20 September 1921[ref]HO 45/11233, The National Archives.[/ref]

The councillors were sticking by their principles and in turn provoking legal action.

The councillors rebel

The London County Council and Metropolitan Asylums Board responded by taking the matter to the High Court. The councillors knew they were taking a significant risk.

The court insisted the money for the central rates would be paid, but had no legal means of forcing this. On 29 July, a procession of approximately 2,000 supporters marched, accompanied by trade union banners and a band, from Bow to the final court hearing in the City, in a theatrical display of solidarity. One banner read: ‘Poplar Borough Council marching to the High Court and possibly to Prison’. The court issued writs for the arrest of 30 councillors for contempt of court, with an indefinite sentence[ref]Despite all voting on the controversial resolution, not all the councillors were issued with writs, which proved to be useful in organising support outside prison.[/ref]. The hope was that the councillors would back down; they were given one month to pay the rates or go to prison.

The government was seemingly not taking their threat seriously. By mid-August Alfred Mond, the Health Minister appointed to deal with the rates rebellion, commented in Cabinet Office papers that the councillors ‘were quite determined to be martyrs’ (CAB 23/27/9). Many of them weren’t strangers to controversy or prison, with Lansbury being sent to prison previously for disturbance of the peace in 1913 as part of his support of the women’s suffrage movement.

From 1 September, arrests of the councillors started to occur over a period of several days. These arrests prompted a backlash from passionate Poplar residents, who flocked onto the streets in support of their elected officials and comrades[ref]John Shepherd. George Lansbury: At the Heart of Old Labour. New York: Oxford University Press. 2002, p.195.[/ref].

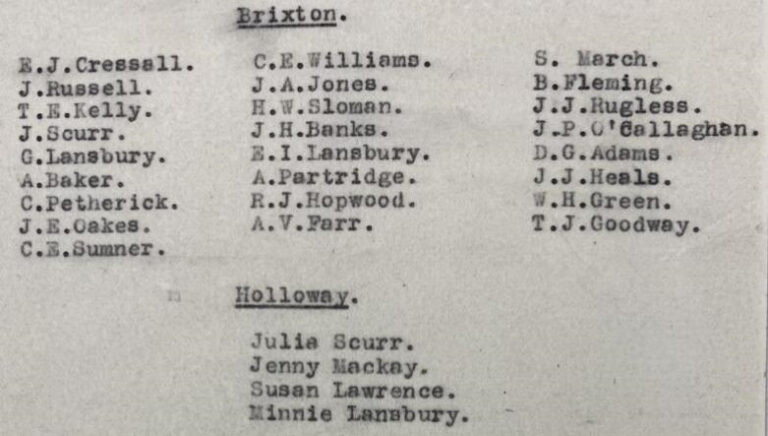

To prison

The male councillors were the first to be arrested and were sent straight to Brixton prison. A few days later the women were arrested and were sent to Holloway, including Nellie Creswell, a seasoned suffrage campaigner and labour activist, who was six months’ pregnant at the time. Many of the councillors had children, caring responsibilities and other jobs, but were still determined to fight. The local community pitched in to support them.

‘I knew these Poplar Councillors were here to make trouble, so gave particular attention to them.’

A letter from a prison official to the prison commissioner

During their prison stays, the councillors continued to be disruptive. Indeed, many of the records held at The National Archives relate to their prison experiences and requests during their time behind bars. George Lansbury, aged 62 at this point, spent significant time complaining about the food, requesting access to books and arguing his right to work while in prison. Lansbury wanted to work on the paper he edited, the Daily Herald. This was controversial as prison officials were concerned that he would publish accounts of his prison experiences, which he eventually did.

The councillors also demanded to be treated as political prisoners and therefore receive the same treatment as first-class prisoners, an argument which harked back to the Suffragette era. George Lansbury wrote in one petition to the Home Secretary:

‘I am a prisoner in this prison for contempt of court in a relation to a rates dispute, I am guilty of no crime, but find myself treated as such.’

[ref]HO 144/5992, The National Archives.[/ref]

The male prisoners also requested access to a football, playing cards and writing materials, and asked for cell doors to be kept open for some of the evening, so they could communicate on council business.

Meanwhile, in the women’s prison Susan Lawrence requested access to Tolstoy and equipment with which to write her latest work on taxation. After complaints the women were eventually given a hospital diet with extras, which included eggs, milk, Bovril, apples and custard (PCOM 7/486).

Shortly before her own arrest Minnie Lansbury, on 5 September, sent a telegram to the prison authorities: ‘my husband and colleagues now being starved physically and mentally for no other purpose than to serve your political spite’ (HO 45/11233).

One of their significant requests was that, as elected officials, they could all meet together, partly to try to solve the issue of the rates. The women were driven by motor car to Brixton prison, where they were given a room to meet in. A total of 34 council meetings were held[ref]John Shepherd. George Lansbury: At the Heart of Old Labour. New York: Oxford University Press. 2002, p.201.[/ref].

Working class support

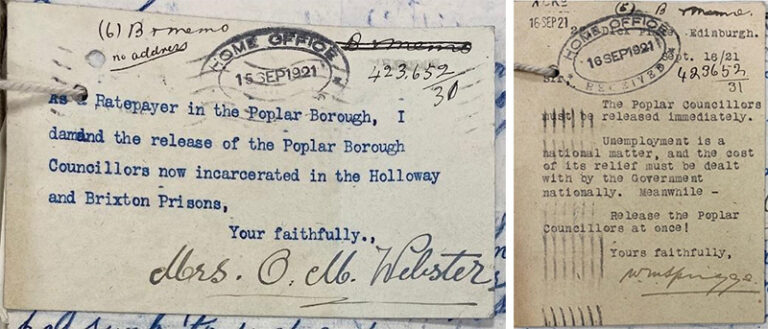

Beyond the prison, spirits were high. Before his arrest, Lansbury had urged their supporters to be ‘physically and mentally organising. No rates, no rent, no taxes, until the right is won!’[ref]Speech by George Lansbury at a Tower Hill demonstration, 28 August 1921. CAB 24/127/80, The National Archives.[/ref] There were nightly demonstrations outside the grounds, with marching bands and the red flag being loudly sung. Trade unions and local bodies passed resolutions of support and collected funds for the councillors’ families. So many letters were received by the Secretary of State that a template letter was sent out in response.

Letters demanding the prisoners’ release and an equalisation of the rates came from organisations as varied as the National Drug and Chemical Union South London Branch to the Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers, Acton. The Locomotive Engineers and Firemen passed a passionate resolution requesting the councillors’ release ‘who are at present imprisoned for their high ideals, and their self-sacrificing interest in the poor of Poplar’ (HO 45/11233). As well as formal resolutions, letters from concerned individuals were also received.

Pressure builds

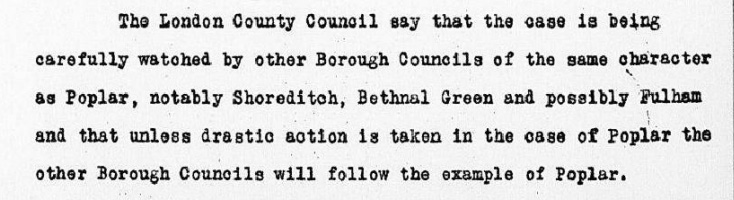

Political support was starting to grow. The Metropolitan Borough of Stepney wrote to the Home Office to ‘protest in the strongest manner’ and threaten to also not pay the rates. Bethnal Green Council had voted to do the same, and Battersea was likely to follow. ‘Poplarism’, as it came to be known, was spreading. Cabinet papers show that a settlement was considered ‘extremely desirable’ and that ‘drastic action’ was needed[ref]CAB 24/128/78 and CAB 24/126/78, The National Archives.[/ref].

The situation came to a head as the councillors applied to be freed and presented two affidavits to the court on 12 October[ref]Janine Booth, Guilty and Proud of it: Poplars Rebel Councillors and Guardians 1919-25. Merlin Press: 2009, p.80.[/ref]. The next day they were released, after almost six weeks in prison (with Nellie Cressall reluctantly released early due to her pregnancy). They never levied the rate nor promised to do so.

Meanwhile, a bill – the Local Authorities (Financial Provisions) Act 1921 – was rushed through Parliament in the winter of 1921. It went a significant way towards equalising tax discrepancy between wealthier and poorer boroughs. The whole affair had gained popular support for the labour movement and proved an embarrassment to the government.

A Poplar Victory Ball was held at Bow Baths Hall. Sam Marsh wrote in the Daily Herald:

‘To everybody, young and old, rich and poor, comrades in the movement and outside friends-including all those resident in every part of the country who kindly took care of our children – here’s our thanks.’

HO 45/11233

However, not everything was positive. Several of the Poplar councillors died within a few years of their imprisonment and a factor in this is thought to have been their stays in prison. Minnie Lansbury, the daughter-in-law of George, developed pneumonia and died at the age of 32, just a year later in 1922[ref]George Lansbury later attributed the shorter lives of Minnie Lansbury, Julia Scurr, Charlie Sumner, James Rugless and Joseph Callaghan to their prison experiences at this time.[/ref].

George Lansbury would later go on to be the leader of the Labour Party. The government continued to keep a watch on him throughout the 1920s, due to his pacifism, socialism and political activism. Edgar Lansbury was to become Mayor of Poplar from 1924 to 1925. Many of the councillors continued their strident political activism, powered by their belief in a better world.

What a farce, were the prison in charge of the prisoners or the prisoners in charge, it looks like the latter. As far as Nellie Cresswell (also described as Nellie Cressall!) goes she was also opposed to the First World War. Anarchy in London with the Suffragettes behind it.

Heroes all.

Thank you for this important recitation of a history too readily passed over or forgotten. The courage of the councillors is to be applauded – I wish someone would take up this struggle as a PhD topic … full of colour and life and opportunities for research. It would make a wonderful book.

Just a note on contemporary relations of Minnie Lansbury and George Lansbury – a relative became Prime Minister of Australia in this century – Malcolm Turnbull – though not for Labor, for the conservative party the Liberal Party of Australia.