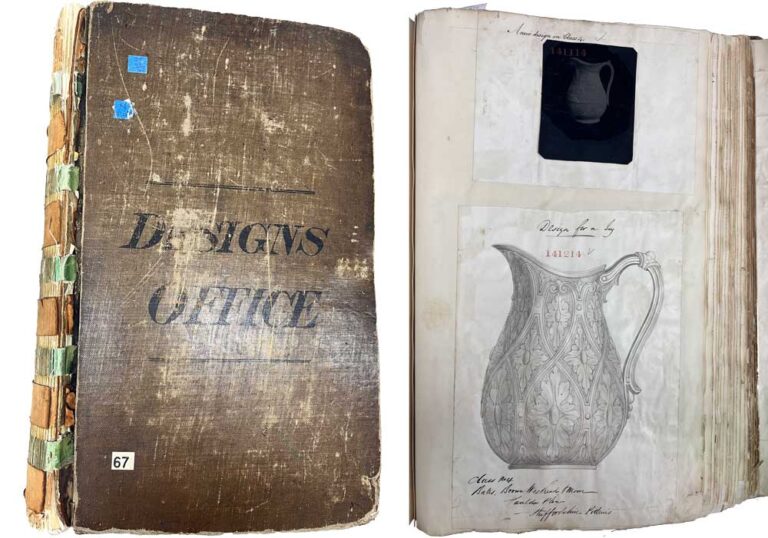

In 2019, conservators at The National Archives made an intriguing discovery while examining The Design Registers, a collection within the Board of Trade records. Among the designs, they found several early photographs mounted on an unusual black backing material.

The distinctive appearance of these images led to further investigation, ultimately revealing them to be pannotypes – a rare 19th-century photographic process. This discovery sparked a scientific research project to uncover their material composition and produce appropriate conservation strategies.

What is a pannotype?

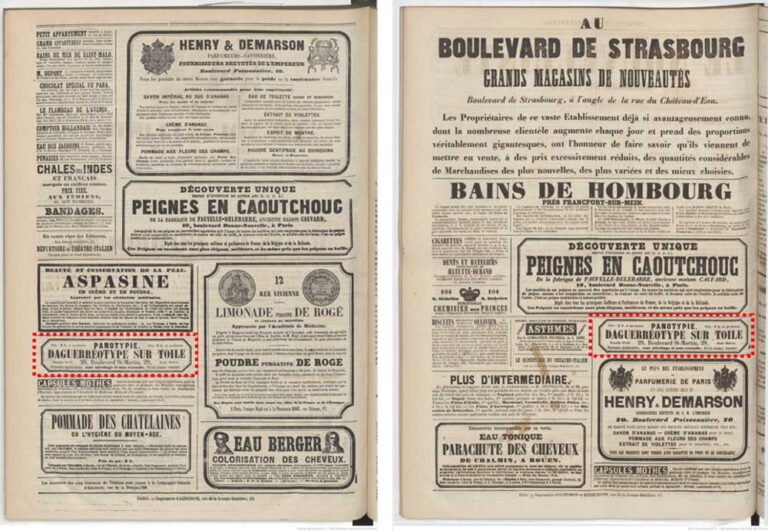

Pannotypes emerged in the early 1850s as an alternative to heavier photographic formats like the daguerreotype. Introduced by Wülff & Co. in Paris in 1853, the process used a wet collodion photograph transferred onto a black-waxed textile support, sometimes referred to as ‘black lacquer’ or ‘oil cloth.’ This innovation provided a lightweight yet durable photographic format, making them a more practical option than metal or glass-based images.

The origins of the pannotype are steeped in controversy. Jean Nicolas Truchelut, a student of the photography pioneer Louis Daguerre, is credited with its invention. However, the Wülff brothers – chemist-retailers in Paris – helped refine the pannotype process and attempted to patent it. Truchelut challenged their claim, and due to leaks in the press, the process was never formally patented.

As a result, little documentation survives about the exact methods and materials used, adding to the mystery surrounding these rare images. Because they were never standardized in the way other photographic processes were, pannotypes exist in multiple variations, with differences in material choices and finishing techniques.

How do pannotypes differ from daguerreotypes?

To fully appreciate the significance of pannotypes, it is essential to compare them to the daguerreotype, one of the earliest and most well-known photographic processes. Invented by Louis Daguerre in 1839, the daguerreotype was the first commercially successful photographic format and remained widely used for several decades.

| Feature | Daguerreotype | Pannotype |

| Support material | Highly polished silver-plated copper sheet | Black-waxed fabric (textile) |

| Image development | Image is formed directly on a silvered plate through exposure to mercury vapours | Wet collodion negative transferred onto a textile support |

| Durability | Extremely durable; can last centuries if protected | More fragile due to fabric support; prone to cracking and adhesion issues |

| Portability | Heavy and delicate; usually encased in glass for protection | Lightweight and flexible, making it easier to transport |

| Image quality | Highly detailed, mirror-like, but requires tilting for optimal viewing | Matte finish, softer contrast, and less reflective than daguerreotypes |

| Popularity | Extremely popular from the 1840s to 1860s, used worldwide | Never widely adopted, mostly produced in France and parts of Europe |

| Conservation concerns | Tarnishing and sensitivity to abrasion | Chemical instability, flaking, and moisture sensitivity |

While daguerreotypes produce extremely detailed and crisp images, they are also heavy, fragile, and require protective cases due to their reflective surfaces. Pannotypes, on the other hand, were intended to be a lighter and more flexible alternative, although their lack of durability ultimately limited their success.

The pannotype’s place in photographic history

Despite their many advantages, pannotypes never gained the widespread popularity of the daguerreotype, ambrotype, or tintype. Their fragile textile backing made them less durable than metal-supported images, and their process was likely too specialized for widespread commercial use. The lack of a patent meant that the technique was never formally commercialized in the way other photographic methods were, leaving it to independent photographers to experiment with and refine.

Pannotypes were primarily produced in France but did make their way across Europe and even into the United States. While relatively rare today, surviving examples can be found in various museum collections, often misidentified due to their unusual composition. Their unique aesthetic – an image seemingly embedded within a black fabric background – set them apart from other photographic processes of the era.

A conservation challenge

The pannotypes discovered at The National Archives exhibited a range of conditions. Some retained their original lustre, while others had developed a whitish haze or had become partially adhered to facing pages in the registers. Their fragility and the unknown nature of their materials posed significant conservation challenges, requiring scientific analysis before any preservation measures could be undertaken.

Investigating the materiality of pannotypes

To gain insight into the composition of these photographs, our Collection Care Department employed both non-invasive and invasive analytical techniques.

Non-invasive analysis

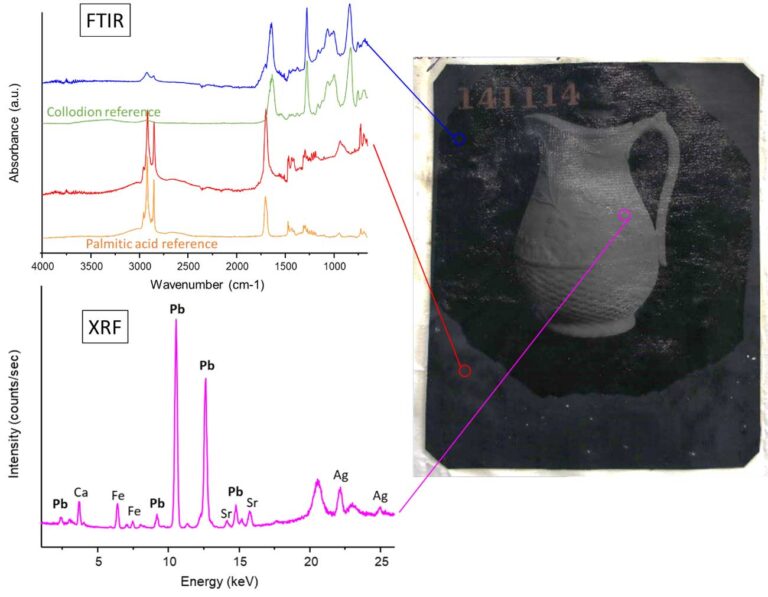

Using forensic-style instrumentation, conservators identified key materials present in the pannotypes:

- X-ray Fluorescence (XRF): This tool detected elements like lead and silver in the white areas of the image, the latter confirming the presence of a traditional photographic process. XRF works by shining X-rays at an object and measuring how the materials inside respond, allowing researchers to identify the materials without touching them.

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): This technique involves shining infrared light on the object and analysing how the light interacts with it, to determine its molecular composition. In this case, using available databases, it revealed collodion in the black areas, confirming the use of a wet collodion process.

- FTIR Analysis of the Whitish Haze: FTIR also showed the presence of free fatty acids in the haze (both palmitic and stearic acids), potentially linked to the degradation of the black lacquered support or the pannotype’s varnish layer.

While these results provided essential clues about the pannotypes’ composition, they did not fully explain their degradation mechanisms or allow for precise conservation planning.

Advanced scientific techniques

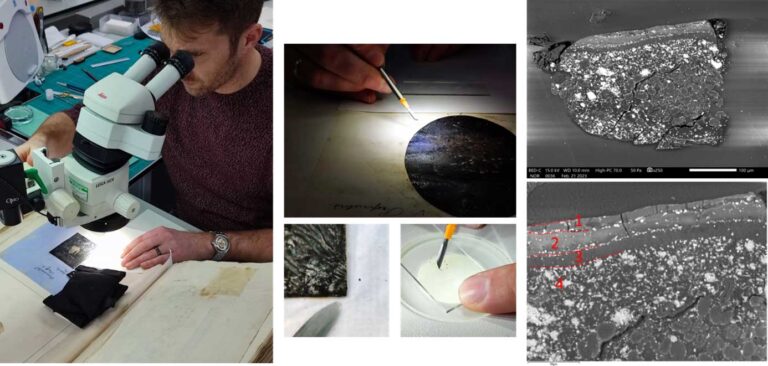

To answer remaining questions, researchers took microscopic samples – each no larger than a coarse grain of salt – for further testing:

- Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS): This method thermally breaks down complex materials into smaller components. This helped scientists explore the molecular structure of the fatty-acid-rich black layer and investigate possible degradation processes. Essentially, it’s like a fingerprinting tool for understanding materials at a molecular level.

- Cross-Section Microscopy: A microscopic sample was embedded in resin and polished carefully to reveal the successive layers. This approach helped visualise the stratigraphy (layering) of the pannotype, shedding light on the craftmanship of this photographic process.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): This technique uses light to create high-resolution images of the pannotypes’ internal layers without damaging them. OCT provides crucial insight into where structural deformations like wrinkling occur, revealing that the black lacquer layer was most affected, rather than the collodion or textile support.

Understanding pannotype degradation

One of the main concerns with the conservation of pannotypes is their susceptibility to environmental changes. Unlike glass- or metal-supported photographs, pannotypes are more prone to:

- Chemical instability: The textile support and collodion layer can react with pollutants, leading to discoloration or surface degradation.

- Physical damage: Because they are mounted on fabric, pannotypes are more flexible than other photographic formats. This can lead to creasing, flaking, and separation of image layers.

- Moisture sensitivity: Any exposure to humidity can cause adhesion issues, leading to pannotypes sticking to adjacent pages or mounting surfaces.

By understanding these factors, conservators can make informed decisions about how to properly store and display pannotypes to prevent further deterioration.

The next steps

Ongoing research at The National Archives is uncovering valuable insights, but there is still much more to explore. Scientists continue to investigate how environmental factors affect pannotype stability and whether alternative conservation treatments could slow down their deterioration. There is also the question of how many more pannotypes may be hidden within the archives, waiting to be rediscovered.

Stay tuned for further updates on this fascinating project!

A good introductory article. In my collection I have several pannotypes, including one on a leather substrate. As a wet collodion process, I’ve always considered pannotypes as a rare variation on the commercially popular ambrotype and later tintype.

A most interesting discovery and Very impressed by the inclusion of spectra and other scientific information in this report.

Fascinating. Much appreciated.

very interesting, I have had a life long interest in the history and practical aspects of all the different methods used to create and preserve photographic images, especially during my years at various Art Colleges and I have never even heard of this process,,, well done and keep up the great work.