At 17:00 on Wednesday 12 August 1942, a B-24 Liberator codenamed ‘Commando’ touched down at Moscow Civil Aerodrome. It was carrying Britain’s wartime Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who had embarked upon a personal mission to meet his Soviet counterpart, Josef V Stalin. Along with being the first wartime meeting between the Prime Minister and the Soviet Premier, it was the first ever face-to-face meeting between a Soviet head-of-state and a Western leader since the Russian Revolution.

However, Churchill’s first trip to visit Stalin would be made under the most sombre of circumstances. Since the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the two leaders had been attempting to work together as allies against one common enemy: Adolf Hitler. Churchill pledged Britain’s support for Stalin and was sending much-needed supplies, including aircraft, tanks and valuable raw materials, to aid the Soviet war effort.

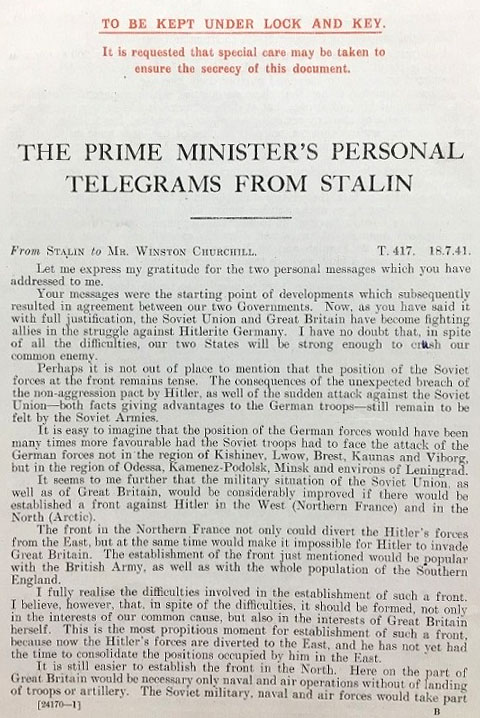

The series PREM 3 contains a printed collection of Churchill’s personal telegrams from Stalin, which detail the initial course of the Anglo-Soviet alliance during the first year of the Soviet-German war. The two consistent points of discussion between No. 10 Downing Street and the Kremlin are the delivery of essential supplies to Soviet Russia and the opening of what Stalin termed a ‘second front’ in western Europe.

From Stalin to Prime Minister, 18 July 1941. Catalogue ref: PREM 3/403/4

‘It seems to me further that the military situation of the Soviet Union, as well as of Great Britain, would be considerably improved if there would be established a front against Hitler in the West (Northern France) and in the North (Arctic). The front in the Northern France not only could divert the Hitler’s forces from the East, but at the same time would make it impossible for Hitler to invade Great Britain’ (PREM 3/403/4).

Churchill later took great care to emphasize Britain’s inability to launch such a front by means of a cross-channel invasion of France in 1942, but it seemed that he did not take Stalin’s request seriously at first. His main objective for the time being lay in supporting Stalin’s armies in their battle against the invading German forces on the Eastern Front. For this, Stalin would be deeply appreciative, as British supplies provided necessary war materials for Soviet industry and equipped Soviet forces to battle the German war machine.

These supplies, delivered by British convoys to the northern Arctic ports of Murmansk and Archangelsk, would be provided under the same terms as the Lend-Lease Agreement with the United States. The voyage to the Arctic was the shortest possible route to the Soviet Union, but for many Allied sailors it was a perilous journey in horrific conditions.

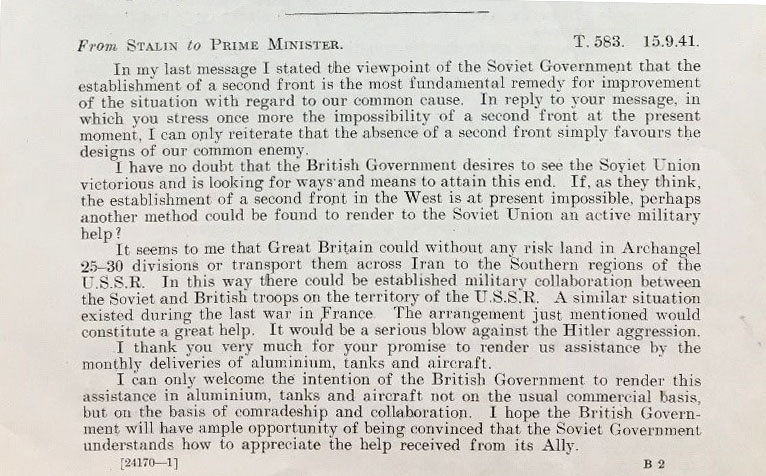

From Stalin to Prime Minister, 15 July 1941. Catalogue ref: PREM 3/403/4

‘I thank you very much for your promise to render us assistance by the monthly deliveries of aluminium, tanks and aircraft. I can only welcome the intention of the British Government to render this assistance in aluminium, tanks and aircraft not on the usual commercial basis, but on the basis of comradeship and collaboration. I hope the British Government will have ample opportunity of being convinced that the Soviet Government understands how to appreciate the help received from its Ally’ (PREM 3/403/4).

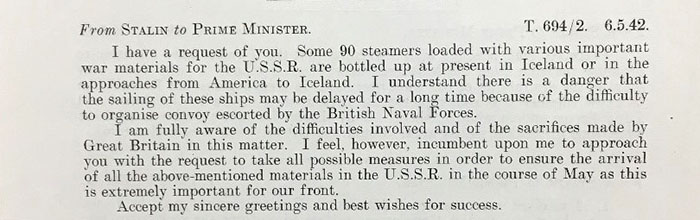

In May 1942, Stalin telegraphed Churchill to request that ships carrying necessary supplies for the Soviet Union be released from ports in the North Atlantic, where they were awaiting better weather conditions before sailing to the Arctic. Due to the imminent operations on the Eastern Front during the summer, Stalin could not countenance the delay of these convoys.

From Stalin to Prime Minister, 6 May 1942. Catalogue ref: PREM 3/403/4

‘I have a request for you. Some 90 steamers loaded with various important war materials for the U.S.S.R. are bottled up at present in Iceland or in the approaches from America to Iceland. I understand there is a danger that the sailing of these ships may be delayed for a long time because of the difficulty to organise convoy escorted by the British Naval Forces. I am fully aware of the difficulties involved and of the sacrifices made by Great Britain in this matter. I feel, however, incumbent upon me to approach you with the request to take all possible measures in order to ensure the arrival of all the above-mentioned materials in the U.S.S.R. in the course of May as this is extremely important for our front’ (PREM 3/403/4).

Indeed, Churchill understood the urgency of these supplies and directed the British Admiralty to move the Russia-bound convoys along with haste. Already, twelve convoys had sailed to the Arctic since the beginning of the Soviet-German war. On 16 May 1942, Convoy PQ 16 sailed to Murmansk and delivered its cargo without incident. The next convoy scheduled to leave the convoy staging area at Hvalfjord, Iceland, was Convoy PQ 17.

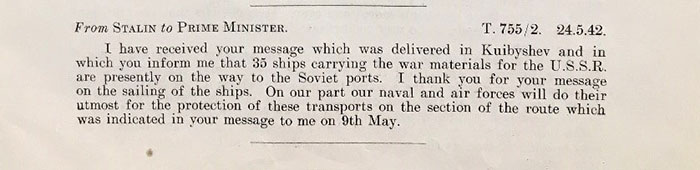

From Stalin to Prime Minister, 24 May 1942. Catalogue ref: PREM 3/403/4

‘I have received your message which was delivered in Kuibyshev and in which you inform me that 35 ships carrying war materials for the U.S.S.R. are presently on their way to the Soviet ports. I thank you for your message on the sailing of the ships. On our part our naval and air forces will do their utmost for the protection of these transports on the section of the route which was indicated in your message to me on 9th May’ (PREM 3/403/4).

On 22 June 1942, Convoy PQ 17 sailed from Hvalfjord, bound for Murmansk. The convoy had 35 merchant ships and was escorted by 27 British and American warships. It would be the largest convoy to sail to the Arctic ports, and was the first major Anglo-American naval operation of the war. The convoy sailed past German-occupied Norway, defying Nazi U-boats and Luftwaffe bombers, and had reached the Arctic Circle with 800 miles to go before reaching their destination.

However, on 4 July, the British First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, fearing that the Norwegian-based German battleship Tirpitz had left port to attack the convoy, issued a baffling order for the escorting warships of the Anglo-American task force to return to Britain. Stripped of their escorts, Convoy PQ 17 was then mysteriously ordered by Admiral Pound to ‘scatter’. Some 31 ships of the convoy accordingly went in separate directions, with each trying to make it to the safety of Murmansk or Archangelsk.

Over the next 48 hours, almost a dozen enemy U-boats and over a hundred Luftwaffe bombers mercilessly attacked the defenceless remnants of the convoy. Of the 35 merchant ships that had set out from Iceland, 24 would be sent to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, taking with them cargoes of 210 aircraft, 430 tanks, 3,350 vehicles and 100,000 tonnes of munitions. 153 Allied sailors perished in freezing waters.

A seething Stalin regarded the decision to scatter the convoy as inexplicable, and was further angered by a consequent Admiralty decision to discontinue the convoy run to the Arctic ports during August. He also used the incident to vent his fury at the postponement of a second front until 1943.

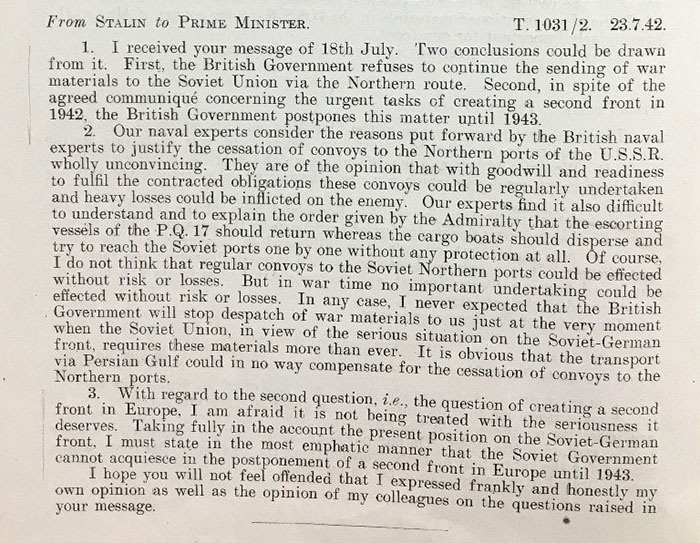

From Stalin to Prime Minister, 23 July 1942. Catalogue ref: PREM 3/403/4

‘Our experts find it also difficult to understand and to explain the order given by the Admiralty that the escorting vessels of P.Q. 17 should return whereas the cargo boats should disperse and try to reach the Soviet ports without any protection at all…With regard to the second question, i.e., the question of creating a second front in Europe, I am afraid it is not being treated with the seriousness it deserves. Taking fully in the account the present situation on the Soviet-German front, I must state in the most emphatic manner that the Soviet Government cannot acquiesce in the postponement of a second front in Europe until 1943’ (PREM 3/403/4).

When Churchill departed for Moscow to meet Stalin, just one month after the PQ 17 disaster, his wife, Clementine, would describe the mission as a ‘visit to the Ogre in his Den’[ref]Clementine Churchill, Letter to Winston, 4 August 1942, cited in Martin Gilbert, Road to Victory: Winston S. Churchill 1941-1945 (London: Heinemann, 1986), p. 161.[/ref]. Codenamed Operation ‘Bracelet’, the Second Moscow Conference is the least discussed of the major summits of the Second World War, but it set the parameters for what amounted to a war-winning alliance. The details of the meeting can be found in the FO 1093 series.

Churchill went to Moscow to tell Stalin there would be no invasion of Europe from the west that year and to clear up any bad feelings after the PQ 17 disaster. However, he came to Moscow with no particular policy goals, but to build a relationship with Stalin and formulate a strategy for victory. Churchill’s decision to travel to Moscow in August 1942 was, therefore, a goodwill mission and an opportunity for both leaders to take stock after recent setbacks.

However, Churchill did have good news for Stalin. Although there would be no second front in Europe in 1942, there would be a major Anglo-American offensive in North Africa by the end of the year, codenamed ‘Torch’. This pleased Stalin, who enthusiastically responded: ‘May God prosper this enterprise’ (FO 1093/247).

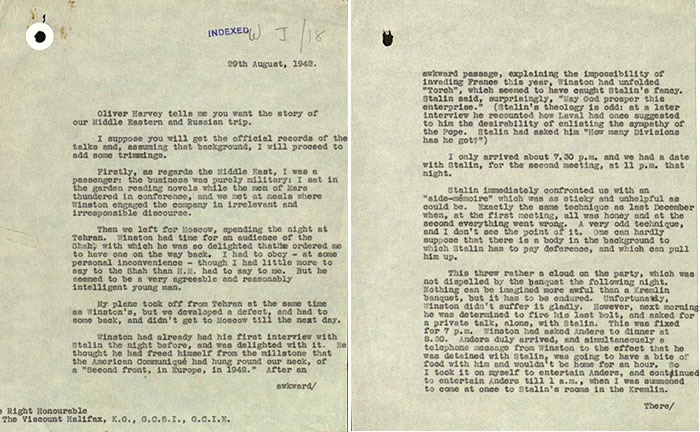

‘Winston had already had his first interview with Stalin the night before, and was delighted with it. He thought he had freed himself from the millstone that the American Communique had hung round our neck, of a “Second front, in Europe, in 1942.” After an awkward passage, explaining the impossibility of invading France this year, Winston had unfolded “Torch”, which seemed to have caught Stalin’s fancy.

Stalin said, surprisingly, “May God prosper this enterprise!”’ (FO 1093/247).

PQ 17 is regarded as one of the greatest naval disasters in history, and marked a low point in Allied relations during the war. It seems clear that Churchill, who had personally found 1942 to be a challenging year of military and naval reversals, felt it necessary to meet his Soviet ally in person following this disaster. The four-day meeting in Moscow, which involved some arguments and recriminations, but also good humour and alcohol-fuelled merriment between the two leaders, laid the foundations for a much better working relationship based on honesty, trust and goodwill.

It could, therefore, be argued that without the gravity of the great convoy tragedy in the Arctic in July 1942, the historic August summit meeting in Moscow would not have taken place.

Sir Alexander Cadogan to Viscount Halifax: Report on meeting between Churchill and Stalin in Moscow, 29 August, 1942. Catalogue ref: FO 1093/247

-Why Stalin did not make the Second Front himself ..in May 1940 ? This is what Churchill should have told Stalin when he brazenly demanded the immediate creation of the Second Front.-How Stalin helped Great Britain when it was fighting alone against Germany?