During the summer of 2022 Delaram Motlagh, a PhD Student at the University of Birmingham, came to work at The National Archives on a student placement. She undertook research on a specific set of nineteenth-century records created by the central poor law authority (or ‘Centre’) in London, the ‘Ministry of Health and predecessors: Circular Letters’ in record series MH 10.[ref]From 1834 to 1847 the central poor law authority was styled the Poor Law Commission. This was replaced by the Poor Law Board in 1848, which in turn was superseded by the Local Government Board in August 1871. For convenience we refer to all as the central poor law authority – or ‘Centre’.[/ref]

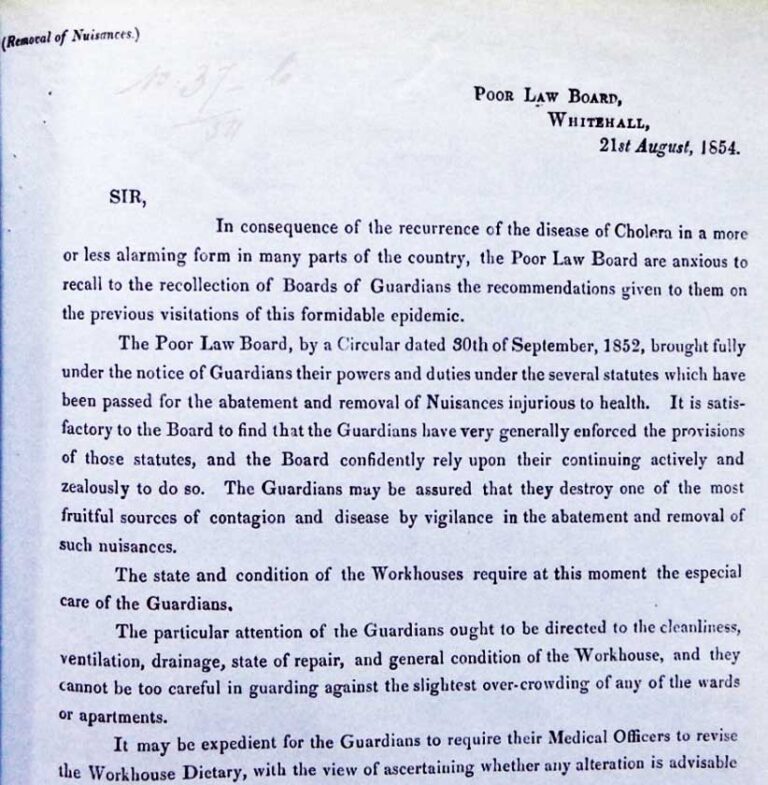

The importance of poor law records to understanding 19th-century society – and the lived experience of millions of English and Welsh people – cannot be overestimated. Most of the English and Welsh population lived at some level of poverty, and an illness in the family or economic downturn was likely to turn common levels of poverty into destitution. The circulars themselves were a communication tool designed to aid the Centre in supervising the hundreds of poor law unions across England and Wales. They were crucial in disseminating what they considered to be essential information and guidance, as well as periodically calling for poor law information which would later be collated and regularly published. In this sense these circulars highlight the Centre’s chief concerns. Delaram’s research task was discerning what these concerns were.

These records are chronically underused, and Delaram and I have put this down to one of two things: either we know so little about them because the catalogue descriptions are rather thin and thus offer little subject content, or interest has been dampened through the complex archival listing, with registers and indexes scattered somewhat haphazardly through the record series. We can do little about the latter cause but hope this blog will address the former. For that, I hand over to Delaram.

– Paul Carter, Principal Records Specialist (Collaborative Projects), The National Archives

‘The Poor Law Amendment Act… affords for advocating sound principles and disseminating useful information’[ref]G. Nicholls, A History of the English Poor Law in Connection with the State of the Country and the Condition of the People, p 120.[/ref]

In 2022, I began to examine and try to understand what the major issues were that the central poor law authority (the Centre) focused upon. This is not easy, as the surviving New Poor Law archive is huge and runs to many millions of books, letters, reports, registers and myriad associated documents. Even though the outlined research proposal focused on a single set of circular letters and was restricted to the period to 1848 to 1871 (the mid-century maturity of the Victorian New Poor Law), this still left thousands of pages of letters. I therefore (very early on) began to focus on the registers to the letters, to provide us with a data set we could more manageably investigate, while referring to individual letters for clarity if needed.

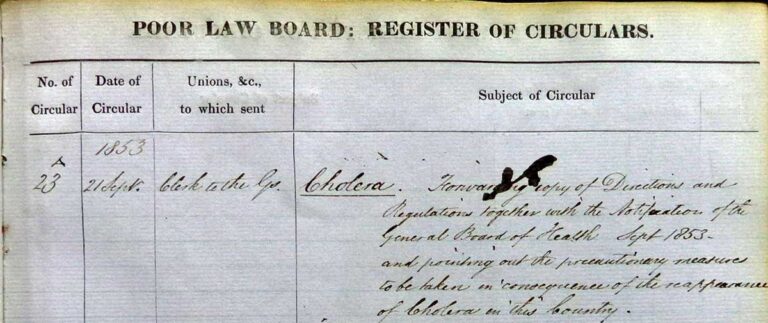

The registers were the means of reference for the Centre’s clerks to find and examine what information they regularly and routinely sent out. The register headings set out the number of each circular, the date sent, who they were sent to (which was often all 600+ unions) and a subject column giving details of the letter itself.

A glance through the orders, regulations and circulars refer us to a variety of recipients for these letters including assistant poor law commissioners, district auditors, elected guardians and union and parish officers. In one sense the subject matter of the circular letters are extensive – they focus on every aspect of welfare such as funding, auditing, duties of poor law officers, salaries and responsibilities of medical officers, pauper children’s education, the earnings of agricultural labourers, emigration and much more. However, despite their vast overall subject range it is clear that the overwhelming majority of these circular letters refer to financial matters.

Many of the circular letters sent early within our period are reminders to unions who have failed to provide the Centre with the information they requested. This suggests that not all unions were responsive to the authority of the Centre. For example, on 20 January 1848 the Poor Law Board circulated a letter which asked for a ‘return of the number of vagrants and trampers relieved in the workhouses of the union’ on the 18 and 19 December 1846. On 18 February 1848, the Centre sent a reminder letter to 101 unions who had neglected to send their returns. This means that around 15% of unions failed to respond and indicates that central controls and surveillance of local practice was somewhat weak in this period.[ref]As an interesting follow up on this case, the Centre had to send a further circular letter in March 1848 to a group of eleven recalcitrant unions to provide the returns, and asking them for ‘an explanation as to the cause of the delay’.[/ref]

Interestingly, I found that there were more circulars published during the early period of the Poor Law Board. In 1848 there were 108 circulars published while in 1870 there were only 41. However, following the case above on vagrants and trampers, it is noteworthy that almost a quarter of the circulars written in 1848 were reminders to unions who had failed to send information requested earlier, and such letters fall away over our period. This suggests that as the Poor Law Board became more established it received more timely responses from unions.

Calculating the chief concerns of the Poor Law Board

After recording the dates, recipients and subject matters of the circulars in a spreadsheet, I was able to develop subject headers to categorise the circulars into topics, which could be used to statistically interrogate the data. Categorising the circular letters proved to be somewhat problematic, with some difficult to classify because they addressed more than one topic. In these scenarios, I placed the circular under the subject header that was most relevant to the subject matter (taking note of the original title created by the Poor Law Board in the ‘Subject of Circular’ column in the original registers).

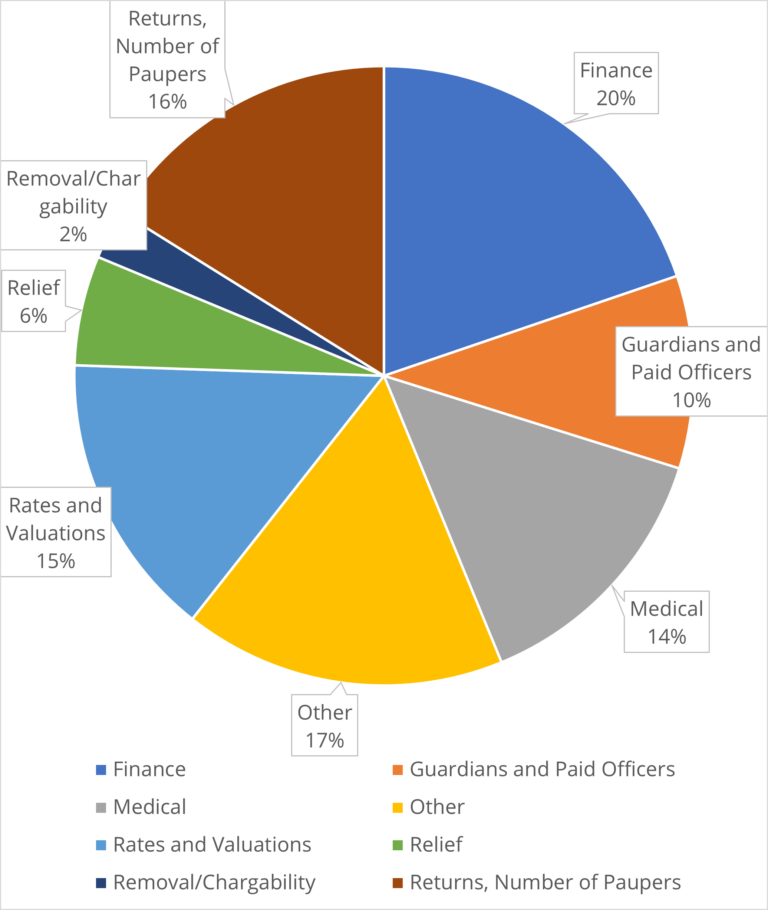

The results are shown in the chart below. Note that subject headings for subjects for which there was less than 30 have been collected and listed as ‘Other’.

In creating and interrogating these subject headers, we were able to make some assertions about what this collection tells us. Of the 1,153 letters:

- 228 concerned general finance

- 186 were about the number of pauper returns

- 172 focused on rates and valuations

- A further 66 and 30 related to relief and removal/chargeability respectively.

All of these were directly or closely linked to finance. Others (many of which are hidden in the ‘Other’ category), such as returns of paid officers, numbers of vagrants or salaries of agricultural labourers, strongly allude to financial matters. We have calculated that around 80%+ of all circular letters distributed by the Poor Law Board focused on financial matters.

This may not surprise us. Although the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 set out the state’s approach to welfare for its poorer citizens, its focus on costs, rating and accounting demonstrates that its implementation and supervision was largely a matter of finance.