After the Second World War in 1945, the young men of Britain were called upon to meet new challenges. In a rapidly changing world, the armed forces still needed the manpower to manage the considerable obligations of its Empire and to deal with new threats posed by old allies. And so, in 1947, National Service was introduced as a standardised form of peacetime conscription for all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 30.

WAR: National Registration Act, 1939: manpower organisation and national registration

More than 1.1 million were conscripted for a one- or two-year stint as national servicemen to help the Army, RAF and to a lesser extent, the Navy. For many young men it was a revolutionary time, giving them experiences, sights and emotions that they would otherwise never have seen or felt. And with the motto being ‘discipline is the end – drill is the means’, all new recruits were in for a shock.

In his book National Service: From Aldershot to Aden, author Colin Shindler captures the memories of the many ex-conscripts who spent ‘time serving’, some across international waters and others who did not make it outside the confines of their barracks.

After attending a medical and joining up in the barracks, new recruits were issued with their own ill-fitting uniform and ammunition boots. All conscripts had six weeks of basic training, during which they were knocked into shape by sergeants under pressure to train them in as short a time as possible, and turn them into soldiers, airmen or sailors. The training included rigorous ‘square bashing’ – endless marching up and down on the drill squares – alongside gruelling inspections, rifle practice, cross country runs, lectures in the art of warfare, fatigues of all sorts, and the continual shouting and swearing from the corporals and sergeants, from morning till night.

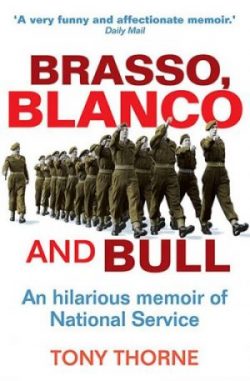

Brasso, Blanco and Bull: An hilarious memoir of National Service by Tony Thorne

Polishing boots and equipment was another torture…or should I say discipline. The strict regime and seemingly endless task of polishing kit and equipment (using Brasso and Blanco) was regarded by many as a mindless drill (Bull) aimed at destroying character, or so they thought. In fact, it had the opposite effect; it strengthened group identity and brought recruits closer together.

To give you an example, Brasso, Blanco and Bull tells the hilarious story of one man who turned up for his medical in 1956 and had little idea of what he would face, or the people he would encounter, over the next two years in service. From the horrors of basic training to the boredom of the drill yard, as well as the unforgettable camaraderie, squad number 23339788 shares his nostalgic moments, with memories and stories that will have you in stitches. It’s a great reminder for all those that served in the National Service.

After training, National Servicemen were often posted to one of Britain’s many garrisons around the world. They could find themselves fighting in guerrilla warfare or involved with riots and civil war, perhaps serving on the front line in Korea, Malaya, Suez or Aden. There were ex-conscripts from all backgrounds, across all ranks, re-living the tension of a post-war Berlin surrounded by the Russians, or enduring the exotic heat of Tripoli in 1948. They might also have been caught up in the brief but intense Suez Crisis in 1956, or the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya between 1952 and 1960. Popular postings were to the Mediterranean or Middle East, although some were better than others. Korea, Egypt and Germany were postings to be avoided…Gibraltar was paradise.

To give you a taste of what life was like for many of these recruits abroad, Up to their Necks is one man’s adventures in the sweltering jungle heat of Malaya. There are stories too, of the camaraderie that develops among many men during their enforced National Service in unknown territory. The Call Up describes (from personal accounts) how recruits could be affected by their experiences but could still enjoy their time in uniform, and embrace the challenge of being away from home.

National Service, which now seems as remote as the British Empire itself, was a shock to the system for many, but others relished the opportunities and experiences it gave them. Friendships formed during National Service could last a lifetime. However, by the end of the 1960s almost 600 young men had been killed on active duty or had died in accidents. The last National Servicemen left the armed forces in May 1963, by which time the Government had decided that the regular army was large enough to deal with any future warfare, including the Cold War.

600 deaths seems too low. You should include the 3 year option which some took for the better pay.

In my Regiment there were 3 deaths of regulars in 2 years in peacetime.