Serendipity often occurs in the course of archival research. While looking for something entirely unconnected, I stumbled upon a file entitled ‘Incident at Kishinev involving British Military Attaché’, and I wasn’t disappointed. It’s a good Cold War story which file FCO 28/459 recounts in detail.

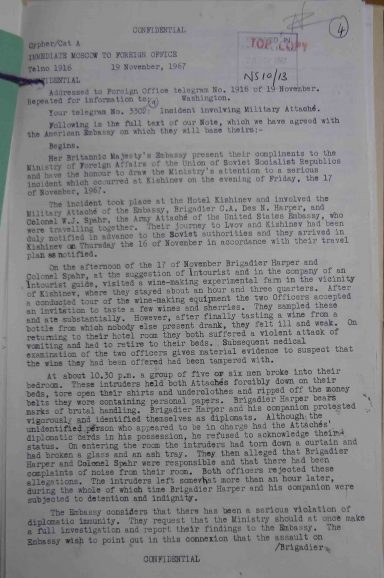

On 18 November 1967, Sir George Harrison, the British Ambassador to Moscow, wrote to the Foreign Office to report ‘an incident at Kishinev’ (now Chișinău, the capital of Moldova) involving the British Military Attaché, Brigadier Harper, and his American counterpart, Colonel Spahr.

Harper and Spahr were on a tour of the south-west frontier region of the Soviet Union, and had travelled to Kishinev from Lvov (now Lviv, in the west of Ukraine) on 16 November. Once there, they were given room 28, on the second floor at the Hotel Kishinev. According to Harper, the room wasn’t up to the usual standards, very small and ‘furnished to a minimum with the simplest and cheapest of Russian furniture’.

Like any other foreigners in the Soviet Union at the time, Harper and Spahr had to go through the state travel agency, Intourist, to build their itinerary. On the 17th, they asked if they could visit Kotovsk (now Hîncești, Moldova), about 35 kilometres away. The request was declined, and the Intourist representative suggested going to an ‘experimental wine plant’ instead.

They arrived there at about 16:00, and were given a tour of the factory before indulging in a bit of wine-tasting – ‘three sherries and one or two red wines’. ‘The drinks’, Harrison reported to the Foreign Office, ‘were sipped slowly and there was plenty of solid food’. When he was debriefed by the Post Security Officer, Harper recalled that

‘he ate five slices of local French-type loaf, well spread with butter and sausage. He also ate some cheese separately. He did not fancy the sprats as he thought the somewhat sharp taste might spoil the wine’.

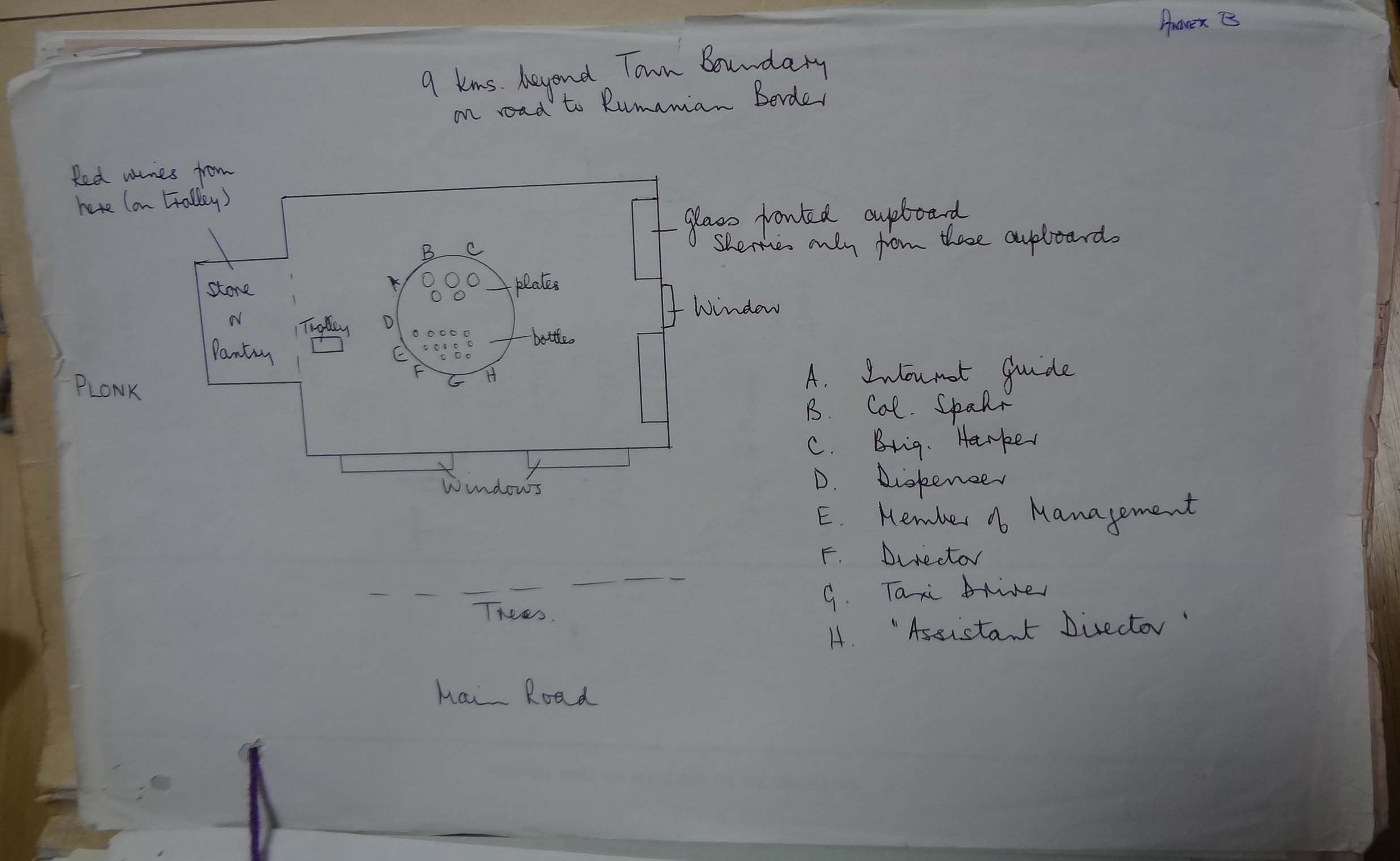

Harper also said that, shortly after sitting down at the table with Spahr, the Intourist guide, their taxi driver, the Dispenser, the Director of the factory and another member of staff, they were joined by a slightly sinister-sounding Assistant-Director, ‘to whom the other Russians seemed to defer’. He barely touched any wine but watched the attachés very closely, as though he was trying to determine how well they could hold alcohol.

As they were about to leave, they were brought a very last wine to try. Then, strangely, they ignored all the obvious rules – the bottle arrived already open and no-one else drank from it, but they still sampled the wine, which was ‘dark red in colour, very thick and very oily. The texture was heavy and the taste was non-existent’.

When they finally left, Harper ‘began to feel a little befuddled’. The wine must have been spiked, because they could barely remember the drive back to the hotel. They just about managed to get back to their room, were ‘violently sick’, and collapsed around 18:45.

Extract from a report based on interrogation by the Post Security Officer on KGB operation against Brigadier Harper (British Military Attaché) and Colonel Spahr (US Army Attaché) at Kishinev on 17 November (catalogue ref: FCO 28/459)

At about 22:30

‘Five or six men, including a militiaman in uniform, a man dressed in white overalls with stethoscope, and a photographer, entered the room occupied by Harper and Spahr and held them down forcibly while they tore open their shirts and underpants in order to get at the body belts in which they carried their notebooks and unclassified tour maps’

The intruders claimed that they had been called in by other guests who had complained about the noise coming out of room 28. A glass ashtray and a tumbler were on the floor, in pieces.

The intruders, presumably a KGB team, left around midnight, having photographed all the attachés’ documents and written a report which Harper and Spahr refused to sign.

Later in the night, they ‘noticed a smell like a car exhaust gases in the room’ and opened all the windows. At 05.30 ‘the telephone tinkled gently and a voice said “Good morning” and nothing else’.

Rather shaken, Harper and Spahr left the hotel at 06:30 on 18 November (having refused to pay for the broken ashtray and tumbler) and returned to Moscow. At 12 noon, they were examined by the American Embassy doctor who took blood, urine and saliva samples. The doctor concluded: ‘This seems to be a case of intoxication with a chemical agent with a sweet, pleasant taste, missible in alcohol or water (…). The agent was relatively short acting and nephrotoxic.’

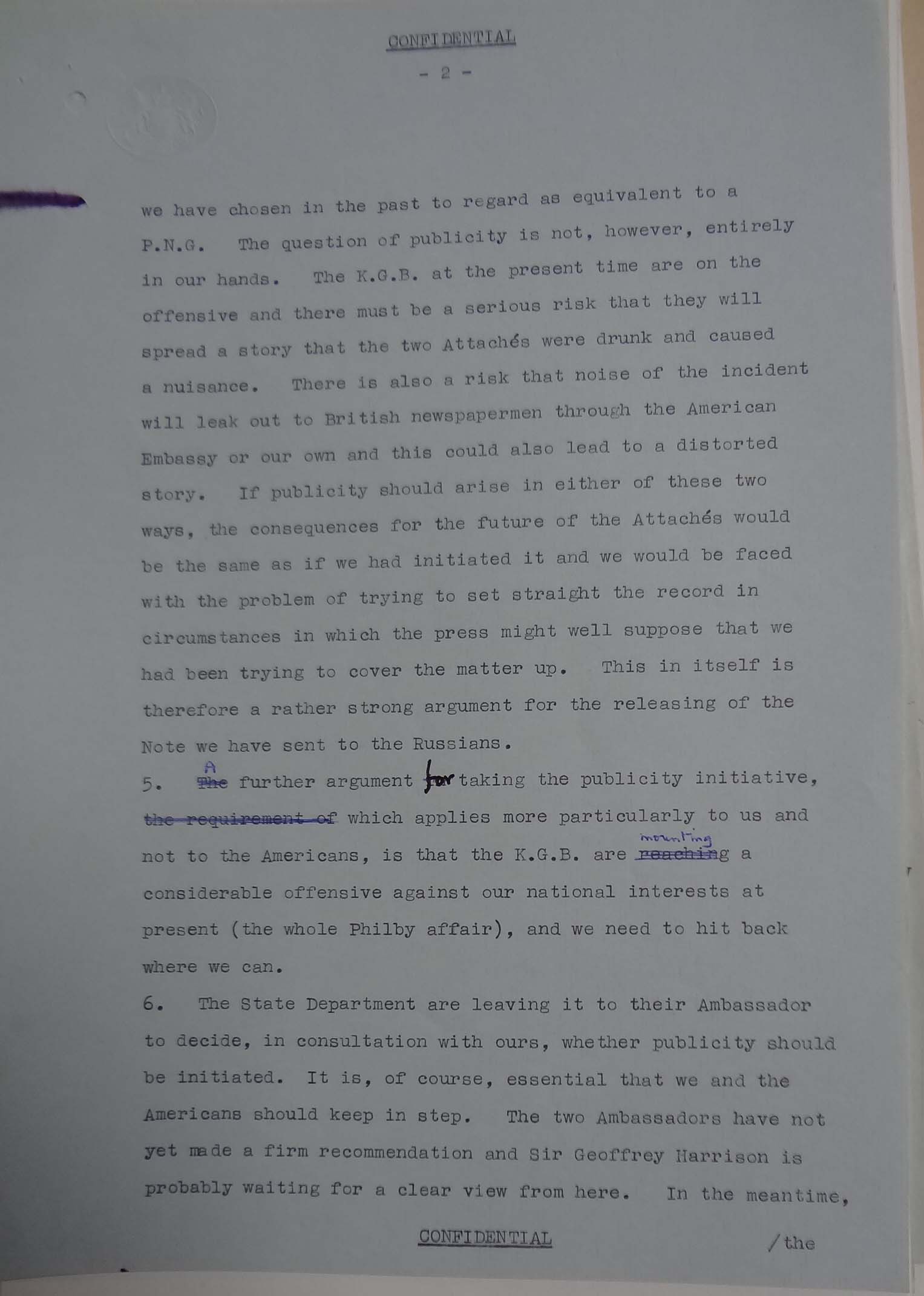

The most pressing issue was that of publicity – or lack thereof. Should the UK and the US protest publicly? Should they lie low, hoping not to make the incident into a ‘story’? In Moscow, both the British and American Ambassadors felt it was slightly above their pay grade and that things should be decided in London and Washington. Their recommendation was that while the attachés had been ‘disgracefully treated’ and ‘the Russians should not be allowed to get away with it’, making the incident public was risky – Harper and Spahr could be expelled from the Soviet Union or confined to Moscow.

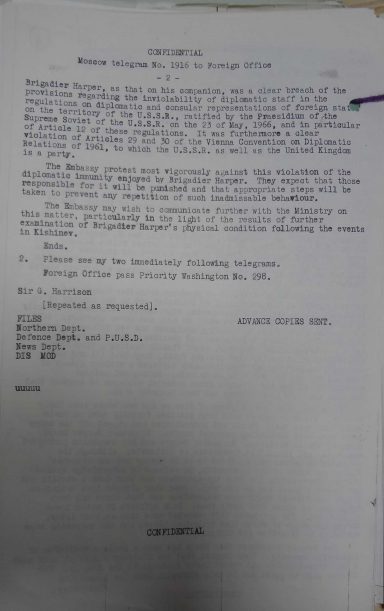

Harrison suggested sending ‘strong written protests’ to the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defence.

- The note of protest, 19 November 1967 (catalogue reference: FCO 28/459)

- The note of protest, 19 November 1967 (catalogue reference: FCO 28/459)

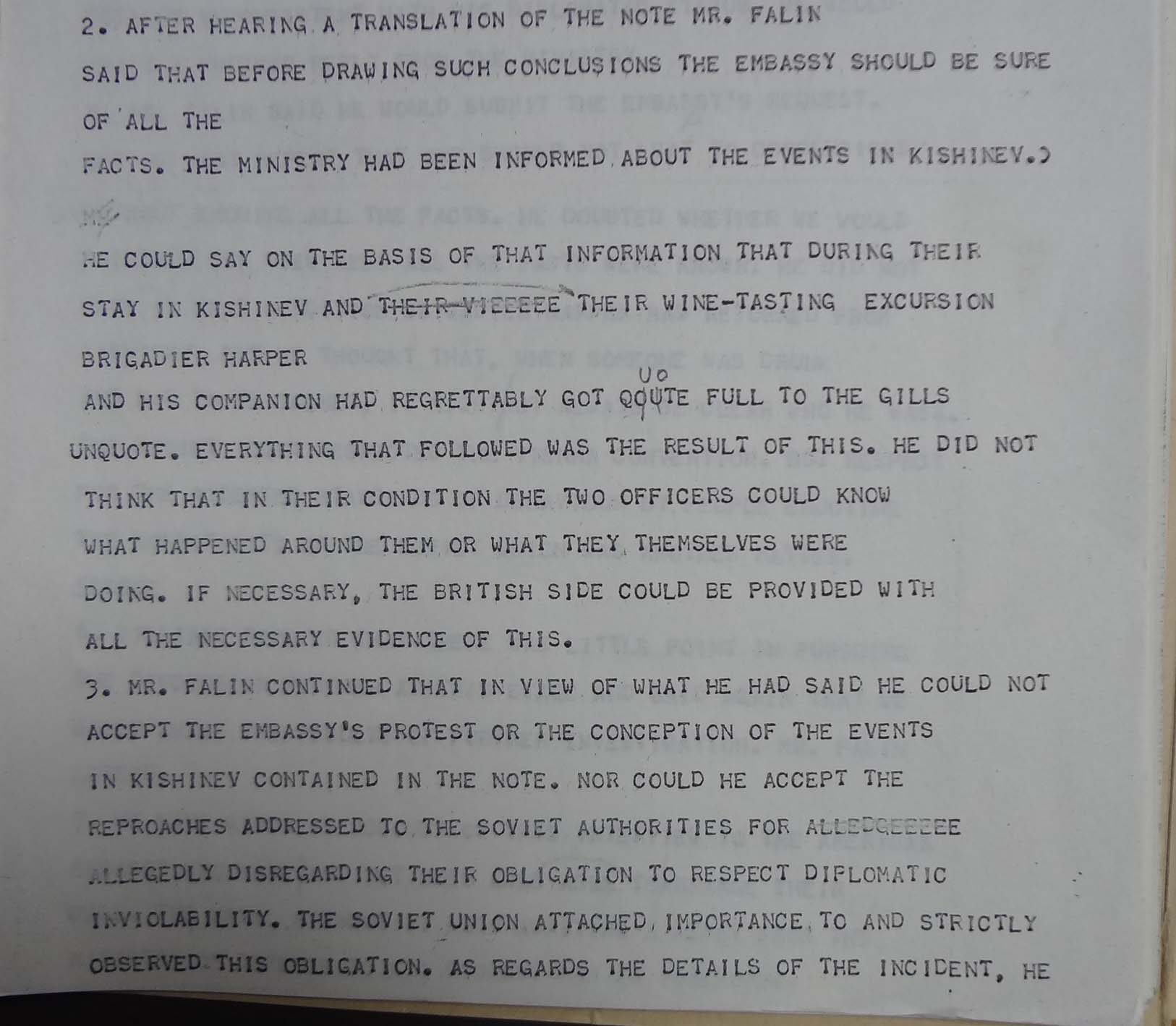

On 20 November 1967, the Head of Chancery, Sir Anthony Williams, called on the Head of the Second European Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mr Falin, and handed him the joint Anglo-American note of protest. Falin suggested the Embassy should get their facts rights. The incident had been reported to him and, according to the information he had been given, ‘during their stay in Kishinev and their wine-tasting excursion Brigadier Harper and his companion had regrettably got quote full to the gills unquote’.

He thought the two attachés were in no condition to understand what was happening or give clear statements. He accepted the note out of courtesy but rejected its terms. He did agree, however, to investigate. Harrison reported:

‘The clear implication of his remarks was that the Russians will not build up the incident if we do not; but can produce plenty of counter material if we do’

As often, there was a divergence of views between Whitehall and the men on the spot. Harrison advised against initiating publicity again, pointing out that it would be easy for the Russians to fabricate evidence. The Americans were also opposed to making things public, as it would put the attachés’ position in jeopardy. Sir Patrick Dean, the British ambassador to Washington, concurred. In London, However, the Foreign Office telegraphed Moscow: ‘on balance it is preferable for us to take the initiative over publicity’.

They thought the story was bound to be leaked at some point and that taking the initiative would give Britain a chance to retain control. The Head of the Northern Department, Sir Howard Smith, wrote:

‘The KGB are mounting a considerable offensive against our national interests (the whole Philby affair), and we need to hit back where we can’.

They were also worried that if the British press got hold of the story, the government might be accused of covering up for the Soviets.

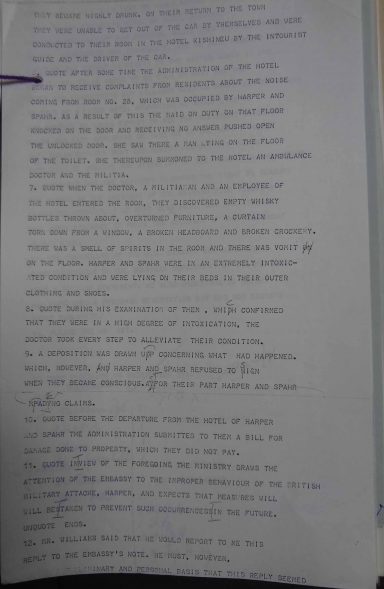

On 22 November, Williams was summoned by Falin, who gave a completely different account of the incident. According to him, Harper and Spahr had specifically requested to visit the wine factory and taste various wines. ‘As a result of this tasting, which [had] continued for three hours, they [had become] highly drunk. On their return to town, they [had been] unable to get out of the car by themselves’.

The hotel, Falin said, received complaints about the noise coming from their room, so a maid opened the (unlocked) door. ‘She saw there a man lying on the floor of the toilet. She thereupon summoned to the hotel an ambulance Doctor and the militia’. When they entered the room, they found empty bottles of whisky, ‘broken crockery’, ‘overturned furniture’, and two very drunk military attachés. Falin concluded with what sounded like a veiled threat:

‘In view of the foregoing the Ministry draws the attention of the Embassy to the improper behaviour of the British Military Attaché, and expects that measures will be taken to prevent such occurrences in the future (…). The Soviet authorities have no intention of drawing the attention of the public to the events in Kishinev. But the Ministry reserves the right to clarify the nature of the incident if the British side issue a distorted account’.

- Falin’s version of the incident, 22 November 1967 (catalogue ref: FCO 28/459)

- Falin’s version of the incident, 22 November 1967 (catalogue ref: FCO 28/459)

On 23 November, the Foreign Office agreed that it would probably be better, after all, not to initiate publicity. They still thought a leak might occur, most likely in Washington. They were right. On 27 November, Newsweek published a very short column on the incident, which prompted enquiries from Reuters. On 29 November, the Soviet state newspaper, Izvestia, published the Russian version of the incident under the headline ‘The Fifth Glass – Or the Merry Adventures of Two Military Attachés’. This was picked up by Reuters, and followed by articles in the Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph, as well as by Parliamentary Questions.

In the end, the story just died, and the attachés resumed their duties normally.

What exactly happened, the why and the how, remains a mystery. Was it all authorised from Moscow or initiated by the KGB at a very local level? Why were Spahr and Harper targeted at this precise moment? Were the KGB looking for something specific? Two days before the episode, they had been approached in Lvov (now Lviv, in Ukraine), by a woman who asked Spahr to take a letter to a defector now working with the State Department. He had obviously refused, but the whole exchange had been observed by their minders, so the KGB might just have wanted to check that they hadn’t taken anything.

The whole Kishinev incident had one very practical consequence: it prompted the ambassador and the Foreign Office to ‘ponder the philosophy of publicity’ and the ‘cost-effectiveness of the very large Service Attachés establishment in Moscow’.

The Foreign Secretary, George Brown, wrote that he was ‘getting a bit fed up’ with reading paper after paper about the incident, but I thought it was a good Cold War story and one which, for once, ended well!

The affair doesn’t seem to have damaged the two attachés subsequent careers, which implies that the Anglo-American authorities accepted their accounts. Brig. Tony Harper, who was already an OBE, received the CBE in 1969 and on leaving Moscow became Commander of the Advanced Base, British Forces in Antwerp. After retirement from the Army in 1971 he held positions including Security Adviser to the Central Treaty Organisation, Ankara, and Instructor at the School of Service Intelligence at Ashford, Kent, where he subsequently became leader of the Borough Council.

Col. Bill Spahr retired from the US Army in 1969 and earned a doctorate in international affairs at George Washington University before spending fourteen years with the CIA as a senior analyst of the Soviet military, retiring in 1986.

Harper died in March 1997 aged 80, and Spahr in June 2011 aged 89.

A really interesting post – not least for the story it tells but also for one it (possibly) hints at.

Under arrangements between the four occupying military powers in post-war/Cold War Germany, there was an agreement that enabled ‘Military Liaison Missions’ from the nations concerned – the UK BRIXMIS team, MMFL from France, the American USMLM and the Soviet SOXMIS – to visit a select number of military exercises to further understanding between the occupiers.

In practice this meant the western allies viewing Soviet activities and vice-versa.

Although they travelled in marked vehicles, the teams also had an intelligence gathering capability (often covert) and would try and get to areas/bases etc where they were not authorised to be.

It’s easy to understand how this situation could be annoying (at the very least) to the troops of the area being visited and there were sometimes official protests made as a consequence.

In addition on the local level, the threat and actual physical damage to MLM vehicles – and on occasions personnel – by soldiers of the nation being observed were not unknown.

Against this background the situation the military attachés found themselves in may have been an attempt by Soviet authorities to get the UK and US MLMs team to ‘back off’ or to retaliate against them for so previous actions.

In conclusion I must say that the above is speculation on my part… but perhaps one day someone or some documents will provide more information.

Forgot to add my previous response to this post that the National Archives catalogue has a number of list of files regarding BRIXMIS and SOXMIS including ones specifically relating to intelligence gathering, arrests of personnel and violence towards members of a BRIXMIS tour.