Diving deep in the archive, you can find some stories which really stand out. Looking at Foreign Office papers about the relations between France and the United Kingdom, one particular item caught my attention. The main title was: ‘Lobster fishing dispute with Brazil’. I couldn’t resist opening it, and I discovered how a simple fishing incident could escalate into a territorial dispute between two countries and become an international issue.

To understand how the whole dispute evolved so quickly from a local incident into a serious matter, you have to look back at the relations between Brazil and France at the end of the 1950s.

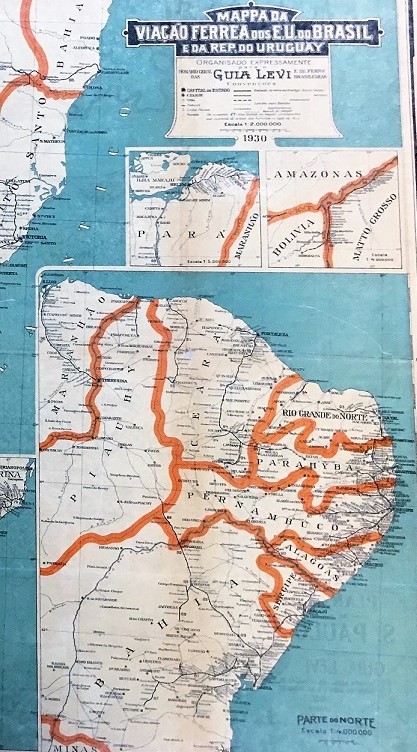

Since the beginning of the 20th century, France and other European countries partly financed Brazil’s railway system, because it had such a big potential as a resource provider (wood from the Amazon forest, for instance). That’s why the main companies working for the Brazilian Government were funded by foreign countries. Among these was the Port of Pará company, located on the Amazon lower river in Northern Brazil.

Nationalist tensions arose after the Second World War, when some Brazilian politicians started to actively fight against foreign interference in the name of their country’s sovereignty. Notably, they focused on the management of ports and territorial waters: agreements were signed to clarify their position and enforce the control of the Brazilian authorities. An agreement with France was signed in May 1956.

So why did the British Foreign Office have such an interest in Franco-Brazilian relations, to devote three whole files to them?

Through the correspondence of the British Embassy in Brazil with the American Department of the Foreign Office, we understand that British interests were mostly commercial. A confidential note of 1959 states that Britain had invested 7 million pounds in the Port of Pará Company. This case stands out for several reasons. First of all, this area is well known for its strategic access to the Amazon River, surrounded by fertile lands and abundant waters. Then, we learn that the British shared their influence with other investors, mostly French (FO 371/155935).

- Confidential note of 21 September 1961, containing strategic information about British interests (Catalogue reference: FO 371/155935)

- Confidential note of 21 September 1961, containing strategic information about British interests (Catalogue reference: FO 371/155935)

In August 1959 a Brazilian Referee, Bonifacio, drafted a bill revoking the 1956 agreement. The bill was passed unanimously. France, deeply involved in the area, asked for arbitration; the French Minister of Finances, Pinay, travelled to Brazil in the autumn to discuss the situation with the government. In March 1960, after a lot of back and forth iterations – which British observers found ‘understandably annoying’ – Mr Hamilyn, member and representative of the Chartered Accountants of the Company went to the British Embassy, asking for advice to stir the Brazilians. The Foreign Office opted for neutrality, judging it unhelpful to enter into the conflict because of the manifest deadlock between the two countries.

Time went by, and the issue seemed to have been put aside for a while. However, in 1961, the newly-elected Brazilian President, João Goulart, sent his Minister of Commerce, Campos, to investigate – and, if possible, bring the matter to an end.

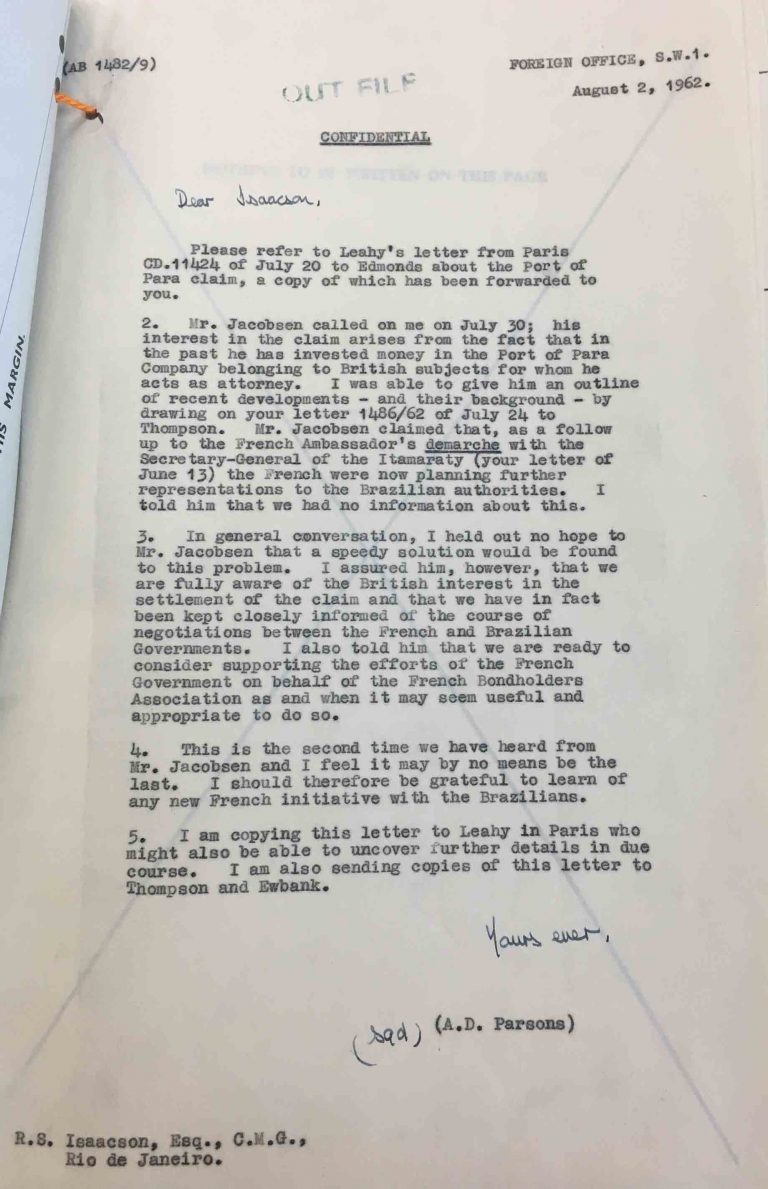

Bonifacio’s Bill and the strong views of the press weighed on the discussions, and another arbitration was required by the French as quickly as possible in March 1962. Once again, the Foreign Office refused to support French interests, this time because of the lack of banking guarantees (FO 371/162163).

Confidential note from the British Embassy in Brazil to the Foreign Office of 2 August 1962 (catalogue reference: FO 371/162163).

It is in this tense period in Franco-Brazilian relations that a fishing incident occurred, and escalated into what we now know as the Lobster War. The central question was: do lobsters crawl or do they swim?

In 1961, a group of French fishermen enjoyed a successful fishing session off the Moroccan coast. They decided to sail westwards in search of lobsters. Rather skillful and ambitious, they finally found an excellent spot off the coast of Pernambuco, in Brazil, where spiny lobsters thrived at depths of 250–650 feet. The Brazilian legislation on fishing borders allowed foreign ships within a distance of 12 miles off the coast, but the fishermen came closer to catch their prey. They were promptly noticed by the locals, who feared they might be ousted from their territory.

The Brazilian Navy reacted to the complaints and Admiral Toscano ordered two corvettes to verify the reports. Having confirmed that the allegations were correct, the Brazilian ships demanded that the fleet of French fishing boats return to deeper waters. The French referred to the agreement of 1956 (which also covered fishing) and refused to cooperate; they immediately asked the French government to send their own military fleet. This prompted the Brazilians to declare a state of alert and mobilize all their ships. On the same day, the Brazilian Minister of foreign affairs, Lima, stated: ‘The attitude of France is inadmissible, and our government will not retreat. The lobster will not be caught.’ (FO 371/169148)

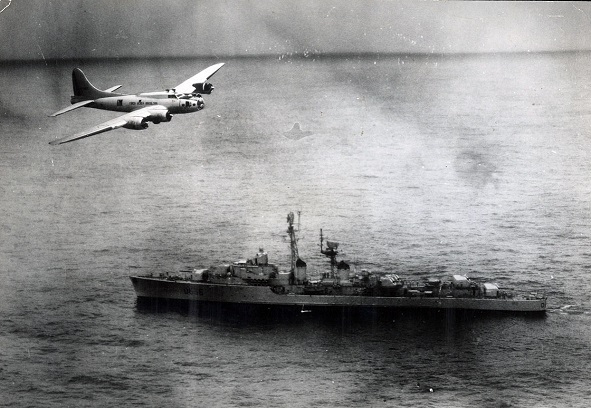

The French President, Charles de Gaulle, found it all very irritating. He thought Brazil was rather ungrateful, given it had benefited greatly from French financial contributions. On 21 February 1961, he decided to dispatch the 2,750-ton T 53 class destroyer Tartu to keep the fishing boats safe. Tartu, however, never reached the fishing boat fleet – it was intercepted and driven away by a Brazilian cruiser and an aircraft carrier.

A Brazilian Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress flying over French destroyer Tartu (D636) off Brazil during the 1963 Lobster War (image: Wikimedia Commons)

Having the upper hand in the situation, President Goulart then gave France 48 hours to withdraw all the French boats. As they refused to leave, the Brazilian Navy captured the French vessel Cassiopée off the Brazilian coast on 2 January 1962.

Although no shots were fired, the tension rose when the Brazilians denied access to French fishermen within 100 miles of the Brazilian north-eastern coast. Their main argument was that lobsters ‘crawl along the continental shelf’ and therefore belonged to Brazil. The French, on the other hand, claimed that ‘lobsters swim’ and, therefore, belonged to anyone catching them in the ocean.

By April 1963, the situation was still unresolved. British observers, once more asked for arbitration, noted that French newspaper ‘Le Monde’ had suggested in March that the Americans were pushing the Brazilians to sit at the negotiation table. This didn’t go down well with Brazil, who had long been competing with the United States over influence in Southern America. The French allegations spooked the Brazilians – they rejected the invitation to have the dispute arbitrated and took the issue to the International Court at The Hague (FO 371/169148).

- Note by the American Department of the Foreign Office, 1 March 1963 (Catalogue reference: FO 371/169148)

- Note by the American Department of the Foreign Office, 1 March 1963 (Catalogue reference: FO 371/169148)

The Lobster War only officially ended on 10 December 1964, after both Brazil and France signed an agreement. The whole incident was resolved by Brazil’s expansion of its territorial waters to a 200-mile zone, which encompassed the infamous lobster area. The agreement also allowed 26 French fishing boats to catch lobsters there over a period of five years.

Although the military conflict ended without any human casualties, the ‘scientific’ argument continued until 1966. Both French and Brazilian scientists had their theories about the actual movement of these crustaceans. In France, the Administrative Tribunal of Rennes endorsed the French theory that lobsters were like fish and swam in the open ocean. They could, therefore, not be considered the property of any particular country. Brazil, on the other hand, claimed that lobsters were like oysters and remained down on the ocean floor, as a part of the continental shelf. Admiral Moreira da Silva, one of the Brazilian experts, said that accepting the French views that lobsters were like fish and ‘leapt’ on the ocean floor would be like Brazilians claiming that when kangaroos ‘hopped’ they should be considered as birds. [ref]http://www.institutojoaogoulart.org.br/noticia.php?id=2403 [/ref]

So, clearly, to swim or to crawl – that’s the ‘spiniest’ question ever!

Very interesting article, related to forgotten disputes on resources with diplomatic consequences.

Lack of resources like water and oil for tomorrow’s 8 billion humans are facing us.

Congratulations.

Very interesting indeed. It must be captivating to relive this story through the archives. Great job.

I remember having heard of an other lobster war, more recent. But I don’t remember where it was…

The “lobster” war – reminds me of the “Emu War” here in Australia in the early 1930’s.

Interesting… in Brazil the history is told as the fishermen having received a fishing authorization for research purposes and once it was understood the only purpose was fishing lobsters in large scale the authorization was revoked. Other than that, the history is told pretty much the same way!