There’s buried treasure in the dry sands of SP 32 – State Papers William and Mary, which has just been catalogued by a team of volunteers. For most of the reign (1689 to 1702) war raged between France and the ‘Grand Alliance’, and much of this series focuses closely on the interminable talks to end it, which were held in The Hague.

To keep him well-briefed, the English ambassador there, Sir Joseph Williamson, received a steady stream of news from correspondents at home – the vagaries of sea conditions in the English Channel permitting. But the balmier breezes of far-flung seas ruffle the pages of these newsletters, too.

Now, if you’ve seen ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’, or read ‘Peter Pan’, you’ll be well aware that buccaneers are a rum bunch – presenting an ugly, unsavoury appearance. Don’t be ashamed! As we’ll see shortly, when we look at the crew of the Adventure who mutinied off Sumatra in 1698, SP 32 provides good documentary evidence for your conventional prejudice.

William and Mary were placed on the throne by an invading Dutch army, and the contested origins of their joint reign partly explain an explosion of high-seas lawlessness during it. By the estimation of some writers of both romance and history, these were the early years of the ‘Golden Age of Piracy’.

Many pirates were passionate supporters of the ousted monarch – King James II (and VII of Scotland). They named their ships after him, forced captives to drink his health, and offered military support to projects aimed at his restoration (see footnote 1).

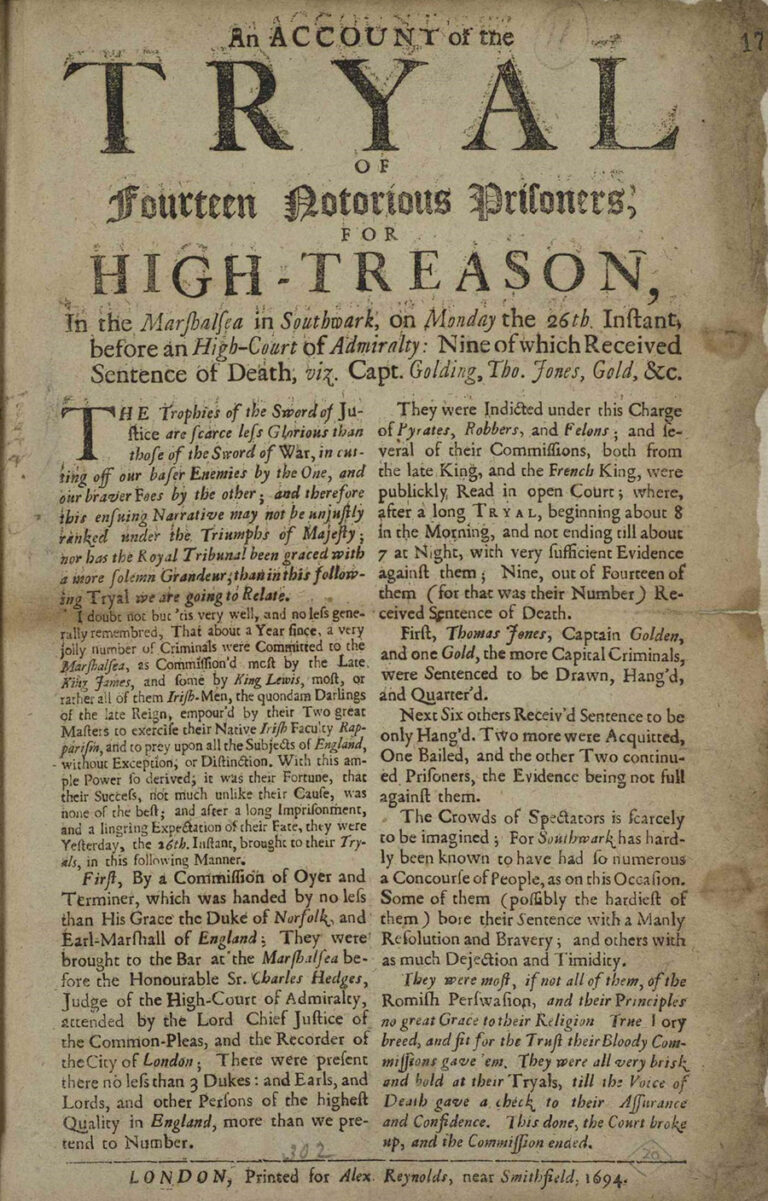

SP 32 documents some Irish Jacobite prisoners of war, captured at sea in 1692, who were sent for trial at the High Court of the Admiralty in London. When charged with piracy, they produced legal commissions from the exiled King. On this evidence, Dr William Oldys, the Advocate of the Admiralty, declined to try them (footnote 2).

The Privy Council was outraged, but the advocate insisted ‘a king may be deposed and deprived of his crown, but cannot lose his right to it’, causing Council members to remonstrate ‘in great heat’. The learned Dr Oldys’ legal career was shipwrecked, and most of the ‘pirates’ eventually hanged.

While, at home, lawyers could be irritating, pirates could create diplomatic ructions abroad. One such irritant was Henry Avery (alias ‘Long Ben’ Avery, or Every), the boatswain of the Charles II. ‘Long Ben’ led a mutinous crew to take over their ship at the Groyne (footnote 3). They set sail for the Indian Ocean in the vessel, which they renamed the Fancy. For six weeks, in August and September 1696, the buccaneers lurked and loitered at Rouges’ Island, waiting to pounce on their prey (footnote 4).

Avery ‘has taken a great ship going to Mecca’, Ambassador Williamson heard, ‘with about 1,000 persons going to pay their devotion there – among which was a Moorish princess whom he ravished – and plundered the ship, which action has much incensed the moors of Surat and other parts of India against the English’ (footnote 5).

Unsurprisingly, the ‘Great Mogul’ (i.e. the Mughal Emperor Muhi-ud-Din Muhammad, better known as Aurangzeb) was greatly offended. Traders and goods at the ‘English factories’ had been seized in reprisal (footnote 6). In response, a reward of £500 was offered for his capture by the Board of Trade, setting off what’s been described as the first ever worldwide manhunt (footnote 7).

Two years later, there was more of the same. Williamson was informed about ‘several piracies committed by one Captain Kidd who, among others, had taken a ship which had on board goods to considerable value, belonging to subjects of the Mogul’ (footnote 8).

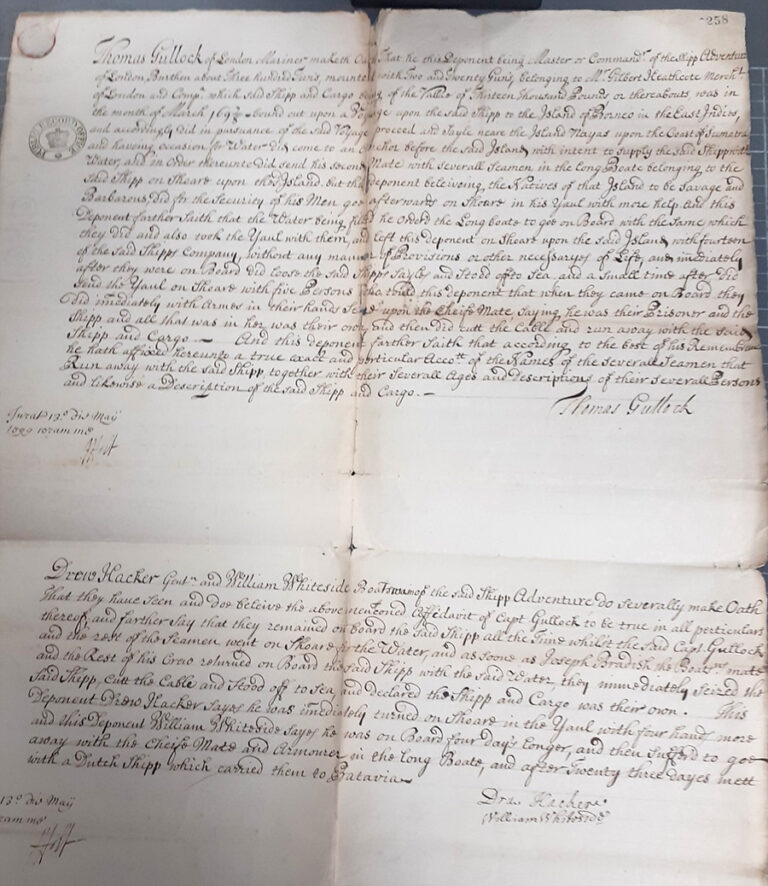

The exploits of this now infamous pirate came to the ambassador’s attention just two months after one Captain Thomas Gullock found himself in a spot of hot water, far away in the East Indies. His ship, the Adventure, was lying off the island of Sumatra when the trouble struck, and SP 32 includes a vivid account of the events, the ship, and its contumacious crew.

The Adventure was a 350 ton, Ipswich-built hag boat, which first saw service as a coal transporter, and with ports configured for that purpose. It had 22 guns, and the narrow stern, flat-bottom and shallow draught of a pink – which would typically be rigged with the triangular lateen sails so useful for the pirate ship sailing close to the wind.

‘She hath five lights in her round house and as many in the great cabin. Her quarter decks come within 15 or 16 foot of her main mast, between which is a capstan from the quarter deck to the entry p[ort]. She hath gangways with two close cabins under each. She is well enough carved, and yellow painted, only the bugilugs are black’ (footnote 9). It’s a description pretty enough to illustrate any ‘Boy’s Own’ pirate adventure.

Adventure’s cargo included lead and iron, and textiles of various qualities. Secured in the great cabin were chests of opium, and $33,500 Spanish dollars. In all, ship and cargo were worth over £13,000 sterling (footnote 10).

The value of the cargo might explain the events of 17 September 1698, when Captain Gullock was ashore on the small island of Nayas, refreshing the vessel’s water supplies. While he was off the ship, the mutineers ‘did immediately, with armes in their hands, set upon the chief mate saying he was their prisoner and that the shipp and all that was in her was their own, and then did cut the cable and run away with the said shipp and cargo’.

Captain Gullock and 14 of the ship’s company were thus marooned ‘without any manner of provision or other necessarys of life’. Four days later, the boatswain, chief mate, and armourer were also cast away, in the ship’s longboat. Thanks to a passing Dutch vessel they were rescued, after 23 days, and taken to Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies (footnote 11).

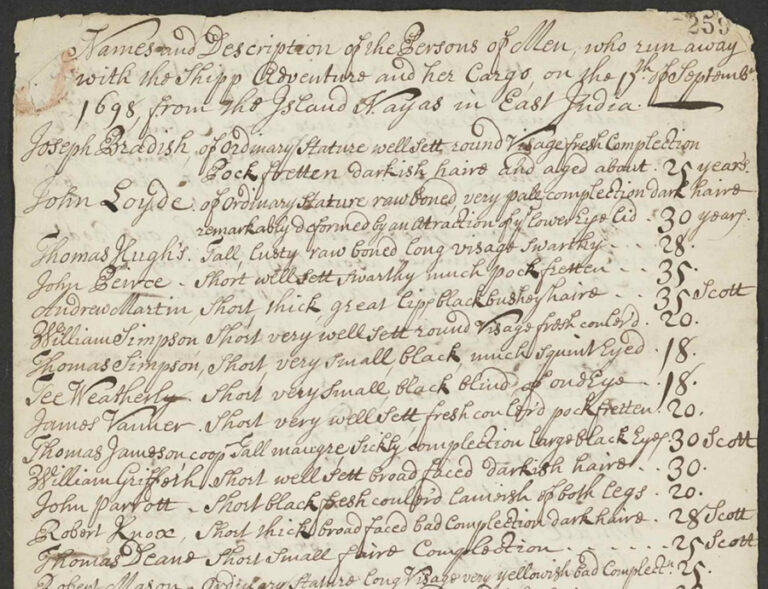

Meanwhile, the mutineers had elected the boatswain’s mate, 25-year-old Joseph Bradish, as their pirate leader. In the description of him later lodged with the authorities by Captain Gullock, Bradish is described as being ‘well set’, having a round face with a ‘fresh complexion’, and dark hair. He was of ‘ordinary stature’, but in this respect Bradish was a cut above most of the crew.

Seventeen of the 25 were described as ‘short’, with only two of the mutineers noted as being ‘tall’, perhaps evidence for the poverty of those forced to make a living at sea, and of a dietary deficiency once aboard. They ranged in ages from 15 to 35 and while ‘Long Ben’ Avery’s crew on the Fancy came from across the seven seas, the Adventure’s pirates sailing under Joseph Bradish, seem all to have been British – four Scots the rest English (footnote 12).

John Lloyd had a ‘very pale complexion, dark hair, [and was] remarkably deformed by an attraction of the lower eye lid’; and Robert Mason had a ‘very yellowish bad complexion’. John Pierce, and James Vanner were ‘pock fretten’, as was Joseph Bradish himself.

Others were described as ‘rawboned’, or ‘down looking’, or ‘much squint eyed’, and Johnny Depp-lookalike Thomas Jameson had a ‘sickly complexion [with] large black eyes’. We have no evidence for peg-legs or eye-patches, but Tee Weatherly and John Parrott (yes, Parrott, as in ‘pieces-of-eight’!) were respectively ‘blind of one eye’ and ‘lamish of both legs’.

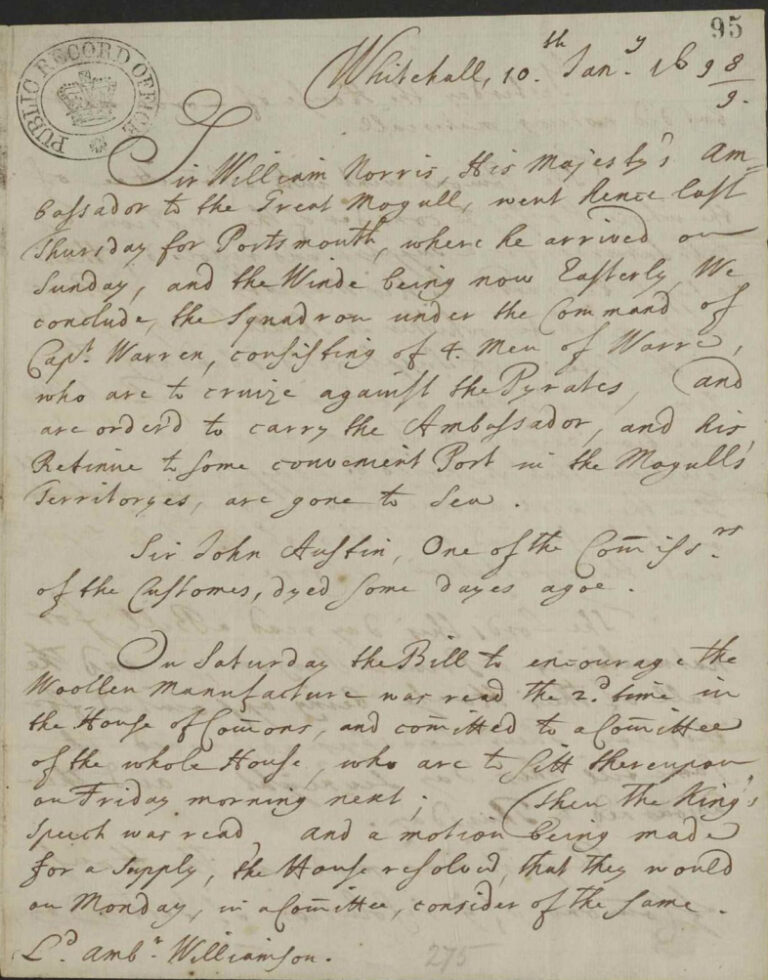

In response to the brazen activities in the South Seas of buccaneers such as Bradish and Avery, an anti-piracy squadron was assembled on the south coast of England, under Captain Warren. He was not long back from the Caribbean on similar duties. In early 1699, the captain set sail for the Indian Ocean and the pirates’ nest at Madagascar (footnote 13). However, while Warren sailed east, Joseph Bradish and his pirates sailed west, arriving in the Caribbean in March 1699. They split their loot, and later scuttled the Adventure, her beautiful black ‘bugilugs’ sent down to sleep with the barnacles on the sea floor off Long Island.

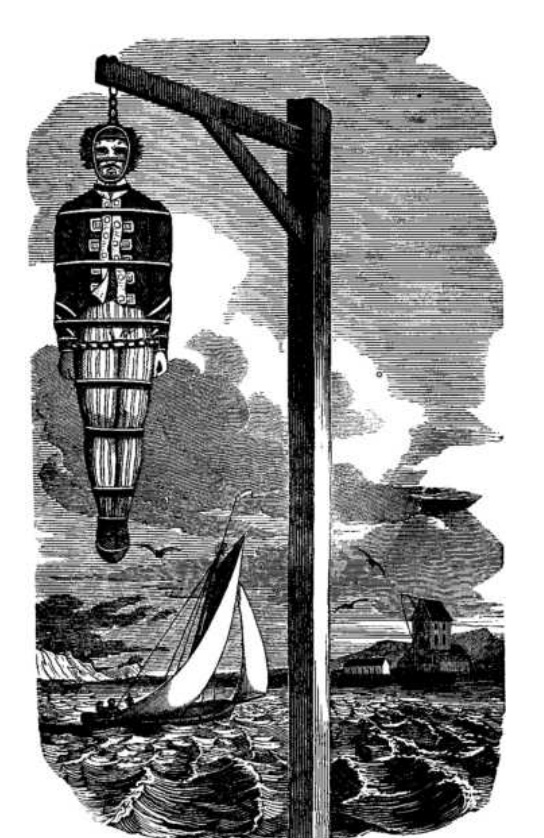

Bradish made it to Boston, but was captured there. He shared his imprisonment, and his eventual repatriation to London on HMS Advice, with none other than fellow cut-throat, Captain Kidd. Both pirates met the same grim end at Execution Dock, and both hung in chains on the Thames Estuary, a grisly warning to others.

But not every buccaneering career ended so badly. Somewhere, in some tropical paradise, ‘Long Ben’ Avery had ‘raised himself to the dignity of a king’ – or so some said. He’d married the ‘Great Mogul’s daughter, and had by her many children living in great royalty and state’ (footnote 14). He was never captured. The £500 reward for Avery went unclaimed. His fabulous treasure remains, perhaps, still undiscovered.

And a treasure map to find it? Well, no. It’s not actually in State Papers William and Mary. As part of the team cataloguing the series, I know that for a fact. We’ve checked thoroughly.

But somewhere – somewhere in the vast treasure chest of The National Archives? Could it be?

Footnotes

- Fox, E T ‘Jacobitism and the Golden Age of Piracy, 1715-1725’ in The International Journal of Maritime History, XXII, No.2., (Dec, 2010) (pp.277-303).

- SP 32/5/90, f.138; SP 32/6/12, f.18.

- A Coruña, Galicia, northern Spain.

- HCA 1/53, ff,10-13; Rogue Island, or Johanna, modern Anjouan, is in the Commoro Islands.

- SP 32/6/113, f.234.

- SP 32/6/109, f.228.

- SP 32/6/130, f.262.

- SP 32/11/40, f.51.

- SP 32/11/147, f.259. The word ‘bugilug’ is unrecorded in the Oxford English Dictionary or in standard dictionaries of nautical jargon, and is unknown to staff at the Maritime Museum in Greenwich. However, by its context here, it clearly means the upright timbers separating the ‘lights’ (or windows) of the round house and Great Cabin at the stern.

- SP 32/11/147, f.259.

- Corresponding to the modern day Jakarta, Indonesia (see SP 32/11/145, f.257 and SP 32/11/146, f.258).

- SP 32/11 passim.

- Ellms, Charles ‘The Pirate’s Own Book, or authentic narratives of the Lives … of the most celebrated Sea Robbers, with historical sketches of the Joassamee, Spanish, Ladrone, West India, Malay and Algerine Pirates’. (Portland, 1837).

- Johnson, Captain Charles ‘A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates’ (first published in London, 1724).

Well, on my mother’s side (Hallamore of Penryn, Cornwall), I have no less than 3 generations of pirates, 1654 -> 1718, not less than 6 pirates in toto. Proof of this by way of 1. legend of pirates in the family; 2. the survival of 1683 New York city piracy trial in which my 6 greats grandfather, John Hallamore, (ca. 1660 -> after 1695), was one of the accused! I have the trial which I transcribed and other documents if interested in me sending? Regards, Neil, South Africa.

Do you think some of the pirates on the “Adventure” were black? eg “Andrew Martin – short, thick, great lipp, black bushy hairs”. Or am I reading too much into the description. There would have been slavery in many of the areas where private ships were operating, so might escaped slaves have made up part of crew on some vessels?

Placing their stamp on original documents, by such as by the PRO here, is an act of VANDALISM!

Very interesting and well worth reading.

I have been researching the naval career of Capt Rupert Billingsley who was born in Barbadoes in 1671, son of Rupert Billingsley while serving with the Barbadoes regiment, who later became the Deputy Governer of Berwick on Tweed.

While I’ve searched the ADM series of Rupert junior’s career , you’ve now given me another source to search.

Absolutely brilliant. I really enjoyed reading this summary. Well done Richard Knight and the volunteers.

Bugilug (or Buggerlugs) How interesting. This brought back memories for my husband. As a child in late 50’s / 60’s in Doddington near Faversham, Kent the term was used for someone with big ears. The had no idea how old the term was!

Certainly wet’s the appetite for further reading

Amazing accounts. Hard to believe that these documents have survived the passage of time to say nothing of fire, floods and other events.

You have work to do. Have you looked at PC1-46/1. Beckford Galley seized by “Rider” (correct name Raynor an ancestor of my late wife) on 30 March 1699. Also material on Capt. Kidd.

See also PC1-46/2&3. Seized a Spanish frigate, 46 guns, by Capt. Every. Good interest here.

My father told me that we came from a lineage that were “Sussex fishermen & Pirates”.

Before the strict regulation of the English Chanel I can see that ANY vessel could “take” another vessel IF they wanted to and IF the vessel was “foreign” it might have been OK or the Customs Men would would take no notice (probably if they got the revenue on what it carried!!)

Are there any records of these domestic pirates?

The National Archives have been the greatest source of information to me.

I am researching the last known days of the Pyrate King himself, Henry Avery, (Sometimes Every, Alias Captain Benjamin Bridgeman). I have found mention of the purchase of three vessels, Sloops? Packet Ships? after the Charles II ,(Renamed ‘Fancy’) was abandoned and gifted to Nicolas Trott Governor of New Providence. Henry Avery and his crew crossed the Atlantic to the West Coast of Ireland arriving and last heard of in August 1696. Two of the vessels were named the ‘Sea Flower’ and the ‘Isaac’ but can anyone put a name the the ‘Third unknown Vessel’?