A previously overlooked document among State Papers in The National Archives (SP 35/77/88) may have the potential to recalibrate, if not to settle, a 300-year-old argument. Was John Erskine, the Earl of Mar, a traitor to the Jacobites? Or did jealous rivals simply trash the blameless reputation of an honest man?

On the death of Queen Anne, Mar raised the Stuart standard at Braemar among the pro-Jacobite Highland clans, in armed opposition to the new King George and the Hanoverian succession. But it has been alleged that he later became a double agent who traded secrets with the enemy to buy favours.

After the end of the Rising, at the exiled Jacobite Court in Avignon, then later in Rome, Mar was ‘King’ James III’s closest advisor. In his gratitude to the leader of the Rising, James (also known as ‘the Old Pretender’) made Mar his Secretary of State, and a duke.

However, Mar was not popular among many in the Jacobite diaspora. Some grumbled that he held James in his thrall. Many felt he’d failed to prosecute the Rising with appropriate vigour. Earlier service to Queen Anne as Secretary of State for Scotland (see SP 54 and SP 55), and his friendship with powerful Whigs raised suspicions. His nickname ‘Bobbing John’ alluded to a perception that he trimmed his actions according to the prevailing political winds, and to his own interest.

Nothing, however, was straightforward in the exiled Jacobite community, where a maelstrom of rumour and factionalism was fuelled by a poisonous cocktail of secrecy, boredom, homesickness and ruined fortunes. In the contest for the King’s ear, there were always those willing to trample on others to get to the top of the greasy pole of Jacobite court politics.

In February 1719, Mar resigned his secretaryship. The date is significant because, later that year, with the help of Spain, another Rising would be launched landing a small expeditionary force in the Highlands. The combined Spanish-Scottish force was ultimately defeated at the Battle of Glen Shiel.

The next opportunity for the Jacobites arose in the election year of 1722 – from the volcanic mood which erupted among British voters whose pockets had been drained in the South Sea scandal. However, before the plot was acted on, the Whig government detected and disrupted it. In the aftermath, the darling of High Church Tories, Francis Atterbury, Bishop of Rochester and secretly the Jacobite leader in England, was convicted by parliament.

Atterbury stormed into exile smouldering with resentment at the ruination of his fortunes. He had no doubts who’d betrayed him – certain it was his long-time rival who’d been managing the Paris end of affairs – the Earl of Mar.

It was not long before Atterbury persuaded James to abandon Mar, who – thereafter – lived in Aix-la-Chappelle (Aachen), ostracised from Jacobite society. He died there in 1732.

What evidence Atterbury showed James is unknown. Had he correctly identified a mole? Or was Mar the fall guy for another failed Rising, a victim of Atterbury’s rage, and of Jacobite paranoia?

Records of the Secret Committee of the House of Commons indicate that the plot had been uncovered thanks to a little spotted dog with a broken leg. Harlequin had been a gift from Mar to Atterbury, and the Jacobite’s coded correspondence was cracked when the identity of Harlequin’s intended owner came to light.

The Commons report also mentioned lords and MPs, the brothel-keeper who is de rigeur in any plot worth recounting, and Atterbury’s secretary Reverend George Kelly who, when the King’s messengers arrived to arrest him, heroically held them at the point of his sword while, with his free hand, he fed incriminating documents into the fire. But Mar’s role was not revealed. Was he wrongly accused by Atterbury? Or had London successfully maintained the incognito of their agent?

Historians have been divided. Gareth Bennett and Edward Gregg, have each argued that official copies of Mar’s correspondence – intercepted at the Post Office, and now among State Papers – prove Mar’s treachery. They say he was blackmailed into writing the letters – implicating Atterbury, and providing documentary evidence with which to prosecute him. The author of Mar’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Christopher Ehrenstein, is explicit in labelling him ‘a double agent’.

But, more recently, this conclusion has been disputed by Eveline Cruickshanks and her collaborator Professor Erskine-Hill. They say the ‘intercepted letters’, which only exist in official copies, are forgeries.

Even though he’d been granted a pension by the British government in 1721, Cruickshanks and Erskine-Hill insist there is no evidence Mar exchanged any information with London.

Lots of Jacobites in exile made applications for pardons and pensions, and James was quite relaxed about this. He understood they had to chase what terms they could. Mar kept him abreast of his dealings on this score – albeit rather after the event.

Almost certainly James did not know, however, that Mar had made his first approaches to London by 1718 – while he was still serving him as Secretary of State. The approach aroused some interest in the ministry, with the Earl of Sunderland suggesting to colleagues that ‘many good consequences’ might arise by granting Mar a pardon.

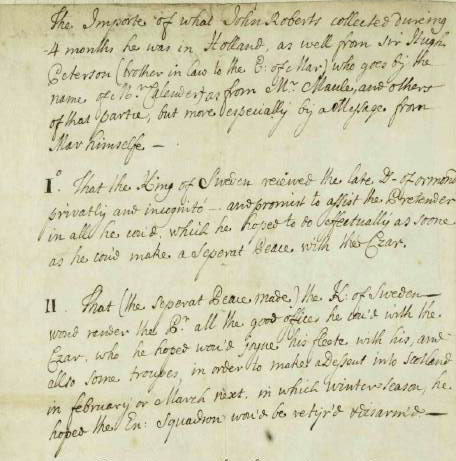

However, James certainly could not have known about the document which has now come to light here at The National Archives. It is a summary of intelligence relating to plans for the Spanish-backed expedition of 1719.

On 4 February of that year, James made a secret dash to Madrid, in order to assume command of the forces assembled by the Duke of Ormond near San Sebastian and Corunna.

Mar left Rome with him. But while the King arrived at his destination, Mar somehow ended up being arrested in Milan, a Habsburg ally of Hanoverian Britain. Then, after being released, he turned up in Geneva, where he was again arrested.

It was widely reported that this had been at the behest of the British, and also that Mar had engineered his own ‘detention’. It does seem he turned up in the Swiss city intending to secure a communications link with the Hanoverian government – his ‘arrest’ a cover.

The document, which has now turned up, was written by a British spy, John Roberts, who’d been on a four-month fact-finding mission in the Netherlands in 1718. For sources, Roberts relied on two of Mar’s relatives – his brother-in-law Sir Hugh Patterson of Bannockburn, and Harry Maule of Kellie a maternal cousin.

But Roberts reveals the principal informant to be none other than the Earl of Mar. The intelligence from him was obtained neither in an intercepted letter, nor from a third party, but directly ‘in a message from Mar himself’.

Mar was giving Jacobite secrets away to London by the first months of 1719, at a time when he was petitioning London for a pardon. It seems he’d given up the seals of office to flee to Milan and Geneva to spill the beans – perhaps on account of having lost James’s ear.

Mar was never actually pardoned, and claimed he only ever received intermittent pension payments from London. What the Whigs demanded of him was more than he was willing to give: namely, a public renunciation of the Jacobite Cause. Mar was too proud to comply.

But in revealing to London the secrets of 1719 Mar had played out his hand. Having resigned as Secretary of State, he had nothing more to offer. Until 1722. In the light of Mar’s actions three years earlier, there can now be little reason to withhold judgment backing Francis Atterbury’s subsequent accusations against his political opponent.

As revealed by Atterbury, and now by State Papers, Mar was a traitor to King James III and the Jacobite Cause; and his treachery reached back further into the Jacobite timeline than has previously been shown.

The 1719 expedition was a failure for many reasons, not least on account of the devastation wreaked on Spanish ships by ‘Protestant winds’. And yet it might be reasonable to wonder what better fortunes could have accompanied the expedition, had intelligence of it not been given to the enemy by John Erskine, Earl of Mar.

Sources:

- State Papers George I: SP 35/77/88; SP 35/11/92

- State Papers George I (the intercepted letters): SP 35/35/6, 10, 11, 12, 13, & 20

- Bennett, G V The Tory Crisis in Church and State 1688-1730: The career of Francis Atterbury Bishop of Rochester (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1975, ISBN 0 19 822444 3)

- Gregg, Edward ‘The Jacobite Career of John, Earl of Mar’, in Cruickshanks, Eveline ed. Ideology and Conspiracy: Aspects of Jacobitism 1689-1759 (John McDonald, Edinburgh, 1982)

- Ehrenstein, Christopher – Mar’s entry in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Cruickshanks, Eveline and Erskine-Hill, Howard The Atterbury Plot (Palgrave, Macmillan, 2004, ISBN 0-333-58688-9)

- Erskine, Stuart ‘The Earl of Mar’s Legacies to Scotland, and to his son, Lord Erskine, 1722-1727’ (Scottish Historical Society, Volume XXVI)

- Earl of Stair to James Craggs (younger), 14 Jan and 27 May 1719, published in Graham, John Murray Annals and Correspondence of the Viscount and the First and Second Earls of Stair (2 vols, Edinburgh, 1885)

Greatly enjoyed reading this !

Thanks Craig!

What a good ‘whodunnit’ and so well-written and fun. Many thanks. Well done!

Excellent work. Well researched and well written.

Excellent work. I wonder what other secrets are hidden at the Archives.

Indeed, Diane. Among the 185 kilometres of shelf space that it takes to store our documents – many of which are still undescribed – you may be sure that there are many ‘hidden secrets’. And with free public access to them at Kew (and online access to our material increasing every year) each one awaits its own Sherlock Holmes to unravel it. Happy hunting!

Love history and this was very enlightening, so enjoyed it.

Such an interesting and revealing read!

As good an espionage tale as any, and with Switzerland, as today, the meeting ground for spies and secret agents.

I don’t think espionage will ever go out of fashion, will it Andrew? Testing the evidence, and peering into the motivation of the human heart, must always offer a challenge of understanding – whether for the Snoop carefully working open wax seals in Walpole’s Post Office, or for the Senior Duty Editor pouring over the latest wires in the modern newsroom!

I enjoyed reading this. It’s always hard to know quite what was going on. I suppose the nearest parallel we can have for the lifetime of many of us is the plottings and interplay of exiles from Eastern European states who had fled Stalin and co but were faced with impoverishment over decades in exile.

The owner of the George and Dragon wargame shop in Glasgow years ago swore blind that Bonnie Prince Charlie in later life was being paid by the British Government. Don’t know what evidence he had for it.

I feel sure the owner of the George and Dragon in Glasgow must have been referring to Bonnie Prince Charlie’s brother Henry Benedict who, after Charles’s death in 1788, became the Stuart claimant. Henry Benedict became a senior cardinal in the Roman Catholic church. During the turmoil in Rome created by Napoleon’s occupation, Henry Benedict was reduced to such penurious circumstances that George III took pity on his kinsman and, in 1800, awarded him a pension of £4,000. This action (together with the fact that Henry Benedict was a celibate clergyman with no heirs) may be viewed as an indication of the extent to which the Jacobite challenge to Hanoverian rule had been reduced by that date.

A good tale but please correct the inaccuracies. As The National Archives, you should be aware that the derogatory Whig term ‘The Old Pretender’ was given to James III of England and Ireland and the VIII of Scotland.

Nomenclature in contested areas such as the Jacobite-Hanoverian dispute is always tricky and, as your post suggests, is still contentious. As a means of preventing friends and neighbours falling out, polite conversation during those days relied on discretion and use of the unexceptional style ‘the Chevalier de St. George’. In eighteenth-century usage the term ‘Pretender’ (or ‘Old Pretender’ after Bonnie Prince Charlie became active in the world) was closer in meaning to what we might mean by ‘claimant’ but, as you say, was still a ‘derogatory Whig term’. Our collection, by its nature, mainly contains (Hanoverian) government records, so the expressions ‘Pretender’ and ‘Old Pretender’ are widely used in our documents. However, in our catalogue entries on Discovery, we usually giving James’s actual name in full – ‘James Francis Edward Stuart’ – in square brackets. This, we hope is a modern-day neutral term which might keep friends and neighbours from falling out! You will note that, in my blog, I placed both the terms ‘King’ and ‘Old Pretender’ in inverted commas, hoping, to alert readers (in an economical manner) to those sensitivities to which you refer.

Tales of intrigue from the past excellently presented. so interesting when these hidden gems are discovered

It might appear Mar was guilty by albeit by a weak connection to parliament.

Very interesting and informative article. Brilliant detective work to unearth the truth regarding the Earl of Mar’s duplicity after such a long time.

Very interesting – had gathered when he left Scotland he had many debtors chasing him. Had also thought he was long time in Avignon but see it was Aix la Chappelle. Thaks you for the post.

From his youth to his old-age, the Earl of Mar certainly was always short of ready money, and most of the choices he made in life can be viewed with an eye to his efforts to escape this inconvenience and to fund his grandiose plans. The real cause in his life was, somehow, to develop his family estate at Alloa and also at his house in Twickenham – and see Professor Corp, below, for information about his plans for his ‘estate-in-exile’ at Chatou, near Paris. You will see that he corrects me in pointing out that Mar spent much of his later years there.

As I explained in my article ‘The Jacobite Duke of Mar’s Changing Dynastic Loyalty during 1719’ (Royal Stuart Journal, 2017), there has been some misunderstanding concerning Mar’s behaviour in 1719. He resigned his position as James III’s secretary of state, not at that time through any lack of loyalty, but because he had also been appointed a gentleman of the bedchamber by the exiled king, and knew that James would need to appoint his secretaries of state after his anticipated restoration from among the politicians already in England. The plan was that James and Mar would secretly leave Rome at the same time. James would travel by sea to Spain and join the invasion fleet at Corunna; Mar would travel incognito north overland through France and join James in England. That, however, necessitated a short journey through the territory of the Emperor (ally of George I), during which Mar was identified and arrested, but allowed to return to Rome. He then left Rome again, hoping to evade capture on his second attempt. Shortly after leaving, however, he received the news that the invasion fleet had been destroyed by a storm, and that there was no longer any possibility of a restoration. That changed everything for Mar, who allowed himself to be identified and arrested after reaching Geneva. From then onwards he concentrated on trying to obtain a pardon from King George I. What Mar wanted above all was to be able to return to his houses and gardens at Alloa and Twickenham, and because a Jacobite restoration could not achieve that he had to try to gain favour with the Hanoverian government. Meanwhile he set about creating a replacement garden at his new home at Croissy-sur-Seine (between Paris and the former Jacobite court at Saint-German-en-Laye).

very interesting, Tales of deception and treachery,

The past and present are very similar, if not the same.

Rue or Rem Holder had a child with Sibylla Graeff in 1694 London but “left the family early”. Was he a soldier or Merchant Marine?

I accidentally wrote that Mar lived at Croissy-sur-Seine. He actually lived and created his new garden during the 1720s at Chatou, on the same side of the river but a little closer to Paris.

Thank you for your reply, Professor Corp. It is a great pity that I did not spot your article before posting my blog.

Just for interest this link is for John Erskine’s memorial in website Findagrave.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/189421057/john-erskine

This sheds important light on the various dilemmas — moral, material and otherwise — that exiled Jacobites faced in this period. My sense is that Edward Corp’s comment is correct: Mar’s ‘treachery’ at Geneva did not affect the outcome of the 1719 Jacobite invasion. But his effort to curry favour at court with the Hanoverians made it difficult, if not impossible, for the Jacobites to mount any further challenge, which the Anglo-French alliance of 1716 had anyway made much less feasible. Nevertheless, this is an important document, accompanied by sound analysis.

Thank you Edward Corp for defending Mar, and for Cruickshanks and Erskine Hill’s wisdom on this matter. The mud has stuck so hard to Mar it is very difficult to remove it. A good deal of the article about SP 35/77/88, notwithstanding numerous factual errors, reveals its bias towards the idea of Mar as a traitor. My monograph on Mar published in 2015 provides a more balanced and objective view of Mar but moreover, I believe, it also for the first time places Mar’s own stated aims and defense of his conduct in terms of his desire for a dissolution of the Treaty of Union of 1707. Mar could not support Scotland’s cause and remain loyal to any monarch or state that opposed that – he put country before king in all his dealings. At one point James VIII was prepared to support a dissolution and for that reason Mar brought out the Highlanders in 1715 to support James’s restoration. Only to find later that James was later persuaded by other exiled Jacobite courtiers, including Atterbury in London, who were jealous of Mar’s influence with James, to withdraw his support for Mar and a dissolution. The document cited above needs corroboration – why should we believe Roberts’s statement? Did Mar think he was a talking to a loyal Jacobite? Did Mar actually talk to him at all? Even worse why ignore Mar’s own written statement on the matter of his motives and loyalty, in order to support a spurious argument? Like all spies in the period Roberts was paid by the inch for any secret he could supply it didn’t matter whether it was true, rumour or invention, as long as it fuelled the Whig oligarchy and its illicit Hanoverian monarchy. Sad to see this nonsense still being promoted by some ‘reputable’ historians.

Thank you for your comments, Dr Stewart. I strongly agree with the points you make concerning the need to evaluate SP 35/77/88. That is why I thought it was very important to write this blog. If one sets aside the ‘intercept letters’, on account of their disputed authenticity, this document (as far as I can tell) is the only one presently identified providing direct evidence, as opposed to the swirl of unsubstantiated rumour during his day, of Mar feeding intelligence to London. I agree that an understanding of how, where and why Roberts came into contact with Mar would help make better sense of it. To my mind, though, the detailed nature of the military and diplomatic intelligence contained in SP 35/77/88, together with the fact that the majority of the content was obtained ‘by a message from Mar himself’, makes it hard to present this in any other light than Mar deliberately assisting the Hanoverian ministry. It is prima facie evidence of Mar not just distancing himself from the Jacobite Cause, but betraying it. I agree that the document is not a ‘slam dunk’ – evidence rarely comes in so compelling a form. But I think it does – as I put the matter at the outset – have the ‘potential to recalibrate’ the argument, even if – as your comments indicate – not ‘to settle’ it. I very much enjoyed your book The Architectural, Landscape and Constitutional Plans of the Earl of Mar, 1700-1732.

Thank you my cousin Dr. Margaret Stewart, for your elegant defense of Mar’s position!

I agree with Margaret Stewart that it was Mar’s Scottish nationalism that set him apart from Atterbury’s faction, and Atterbury was disrespectful and destructive in his relation with Scottish and Irish Jacobites. Her revelation that James reneged on his agreement to dissolve the unpopular union of Scotland and Ireland is important and explains much of the later difficulties and ambiguities in his relation with some English Jacobites. I also think you should have published the whole document, so that we have a chance to evaluate whether the paid spy Roberts could be trusted. It is interesting that Jonathan Swift maintained his admiration of Mar up until and after Mar’s death. Good for Edward Corp for always providing sound documentary evidence. I think the “double agent” charge is still too flimsy to be accepted as accepted proof.

The comments by distinguished contributors are interesting, I shall study them in more detail.

As a rollicking good yarn, I do like the story of keeping your enemies at bay with your sword in one hand while the other is burning the incriminating letters/documents. That ought to find its way into a novel.

In case anyone might be interested, here is a link to my recent article on the Protestant Wind, published in online Historia magazine.

https://www.historiamag.com/the-protestant-wind/