This blog is connected to the online premiere of a double bill of new audio dramas inspired by records at The National Archives relating to the Irish War of Independence: The Bulletin and Persons Unknown. To book a free place to this event, on Thursday 24 November at 19:00, visit: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/the-bulletin-and-persons-unknown-tickets-453912613847.

In the aftermath of the failed 1916 Easter Rising, public opinion underwent an extraordinary shift away from the union with Britain and towards the notion of an Irish Republic. Irish people were outraged by the reports of executions of rebel leaders and imprisonment of hundreds of nationalists.

The British government’s threat to introduce conscription in 1918 further inflamed opinion, and loyalty to the Empire was soon to become a thing of the past. The election of 73 Sinn Fein MPs, representing republicanism, to the Westminster parliament, meant democratic legitimacy for some form of self-rule.

The National Archives’ records help narrate most of the strands of the story of the Irish War of Independence 1919-21, and this blog attempts to illustrate the importance of specific collections.

The Royal Irish Constabulary

The Inspector General and County Inspector Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) monthly reports – CO 904/108 to CO 904/118 – document the attacks on the British symbol of law and order in Ireland, the police. These records concern the intimidation of police officers, attacks on RIC barracks and detail the new concept of ‘guerrilla warfare’, of attacking a target and retreating with captured arms.

Within a year, huge tracts of the country were without police and the Irish Volunteer republicans took over. Many RIC men resigned, afraid for themselves or their families, and consequently recruitment to the RIC ground to a halt.

Within this collection there is also evidence of the funding for a new Sinn Fein government. The Dail (Irish parliament) had been set up in January 1919 and its Finance Minister, Michael Collins, established a Dail Loan Scheme to fund both a new government and legal system. CO 904/110 contains evidence of the organisation of this bond system.

The ‘Black and Tans’

The decline in RIC manpower in 1920 is recorded in HO 184/61, and soon the Westminster Government accepted that new recruits were needed. The decision to take non-Irish recruits was made by the Inspector General of the RIC, and recruitment for what would become the ‘Black and Tans’ force began. The Cabinet sanctioned this in May 1920 (CAB 23/21 and CAB 24/106/18), and in July it was decided to supplement the ‘Black and Tans’ with ‘Auxiliaries’ or former British Army officers (recorded in CAB 24/109 and CAB 24/110).

The Auxiliaries files (HO 184/50-53) cover the recruitment and retention as well as operational movements of the new personnel. Many were English and attracted by the good pay that the Auxiliary Division Royal Irish Constabulary (ADRIC) offered.

The propaganda ‘war’

The propaganda campaign with foreign governments, newspapers and politicians was an important pillar of the war and Dublin Castle, from which the British ran its campaign, kept records of Sinn Fein and other sympathetic lobbyists from Europe and America. Within CO 904/162 there is a pamphlet published by the Committee for American Relief in Ireland, a philanthropic organisation, documenting atrocities committed by Crown Forces. Elsewhere in CO 904 209 18 there are confiscated republican song sheets with titles such as “If you’re Irish, Were goin’ to suppress you!’ Moreover, in CO 904/211 there is evidence of British surveillance of members of Cumman na mBan, the republican women’s organisation.

It was the news propaganda ‘war’ with Sinn Fein, though, that most preoccupied Dublin Castle. There are several files cataloguing the administration’s concern with losing the sympathies of not just British but foreign newspapers. Within CO 904/168 there is correspondence between Basil Clark, the head of the Public Information Branch (PIB), and his superiors in London, detailing difficulties with the Irish press. By January 1921 Clarke was advocating ‘propaganda by news’ – sticking to bare facts in a news story and gaining credibility with journalists for the truth. Unfortunately for Clarke, the Army and RIC had their own press headquarters and did not always align their reports with the PIB.

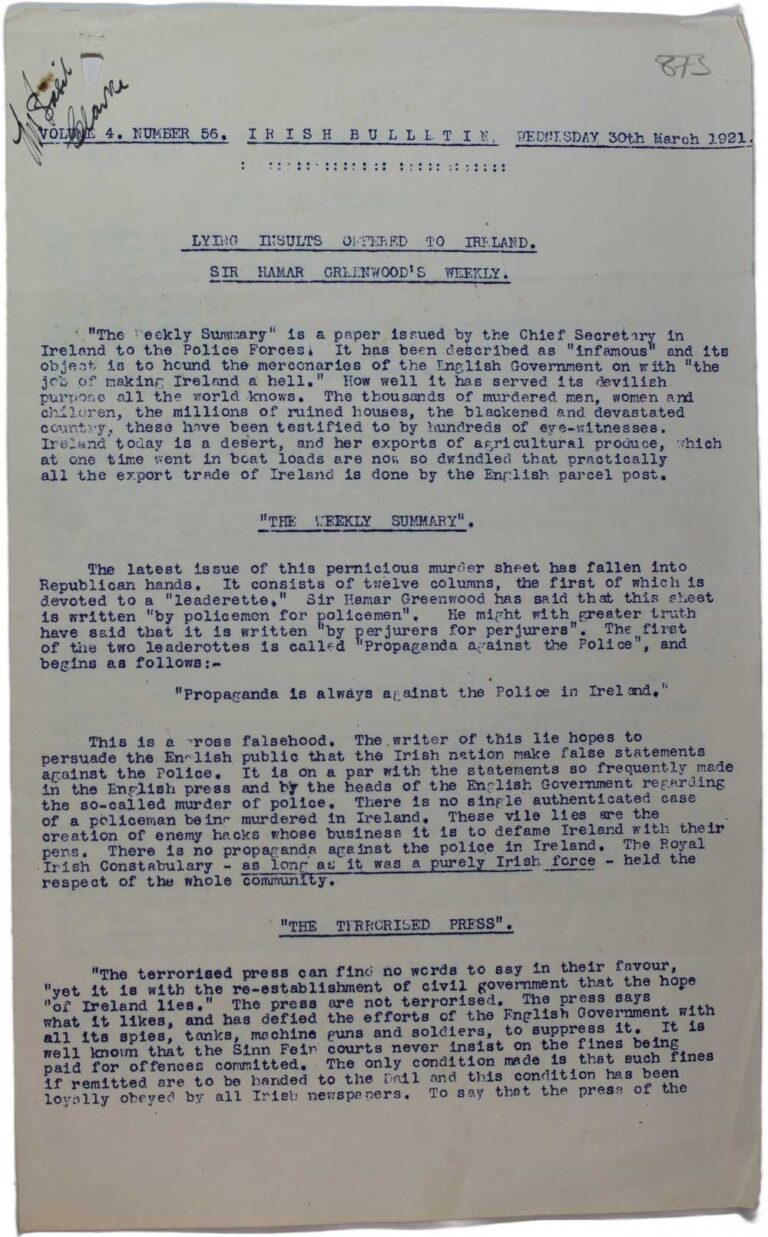

The outstanding example of failure to consult strategically was the production of a fake ‘Irish Bulletin’. The Bulletin was a newssheet published by the Dail/Sinn Fein and distributed to foreign journalists and prominent individuals in Britain, Europe and the United States. After the Bulletin’s offices were raided in March 1921 by the Dublin RIC, two of its officers hit upon the idea of producing fake editions. The fake newssheets were soon seen for what they were, however, as they exaggerated the misery of the Irish people. The same officers also produced the Weekly Summary, an RIC newssheet, that soon became notorious for the way it appeared to actively encourage reprisals.

Inquests and military courts

One such reprisal was the murder of IRA Commander and Lord Mayor of Cork, Thomas MacCurtain, shot on his doorstep in March 1920. The details of this case in CO 904 47/B are illustrative of how Irish public opinion had turned against the British administration. A few months later the IRA would assassinate one of the RIC’s new Divisional Commissioners, Colonel Gerald Ferguson Smyth, for allegedly stating at a meeting of RIC policemen at Listowel, Kerry, that ‘no policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man’. An account of his assassination is contained in the comprehensive report of the British Army’s actions during the War in WO 141 93, grandly titled ‘Record of the Rebellion in Ireland and the part played by the army in dealing with it’.

In August 1920, Parliament passed the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, which replaced all coroners’ courts such as the MacCurtain case with military courts. This was because inquests conducted by local authorities were increasingly finding British soldiers liable for civilian killings. These courts, conducted by three British military officers, are in WO 35/146A-160. They include cases of murdered civilians (often by persons unknown), as well as accidental deaths. The Act also provided for the replacement of trial by jury with military courts-martial in areas where the IRA activity was dominant. Such a policy eventually led to martial law in many parts of southern Ireland.

On 12 August 1920 the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney, was arrested and charged with sedition. MacSwiney was tried by court martial and went on hunger strike. These records are still retained by the Metropolitan Police in MEPO 38/110.

Very soon after his hunger strike began, British policy in Ireland went centre stage in the international press as MacSwiney was transferred to Brixton prison, London. His death on 25 October, after 74 days of hunger strike, led to a huge propaganda victory for the republicans, with the Lord Mayor’s funeral evoking worldwide sympathy and an outpouring of emotion.

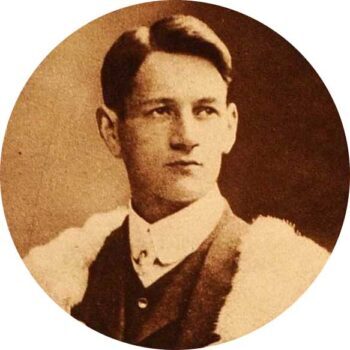

Likewise the hanging of 18-year-old Kevin Barry for participating in an ambush on British soldiers in Dublin (detailed in CO 904/42/1) illustrates the harsh calculations being made about how to deal with the republicans both in Dublin Castle and London.

Dublin Castle officials

Some of the most fascinating pieces of correspondence in the archives are the internal memos or diaries kept by Dublin Castle officials.

Foremost amongst these are those by Mark Sturgis, an assistant to John Anderson, the latter of whom was the Under-Secretary for Ireland. Sturgis kept a diary (PRO 30/59/1-5) from the time he arrived in Ireland in July 1920 until his departure in January 1922. The diaries are a popular source for quotations by historians and reveal much about the efforts of the British administration to negotiate a peace with Sinn Fein.

A really interesting and incisive blog that covers the war of independence in Ireland by showing us the dirty war that the British government undertook a century ago. Interested to find that the Dublin Castle administration was involved in fake news before the modern era. Thank you for posting this set of records that will help individuals like myself discover more stories of our heritage.

Are records of Internees in the War of Independence at Newbridge Army Camp available anywhere?

Thank you for your comment.

For help with this, please use our live chat or online form.