Historical evidence is dominated by visual materials, from archival manuscripts and newspaper print to images, like paintings and photographs. The first recordings of sounds were not made until the late 19th century. While the sounds themselves may be lost to history, records can still shed light on the soundscape of the past. Material, in the form of correspondence, reports and even some images, found in the state archive, can bring back to life the sensory experiences of citizens.

Health and noise

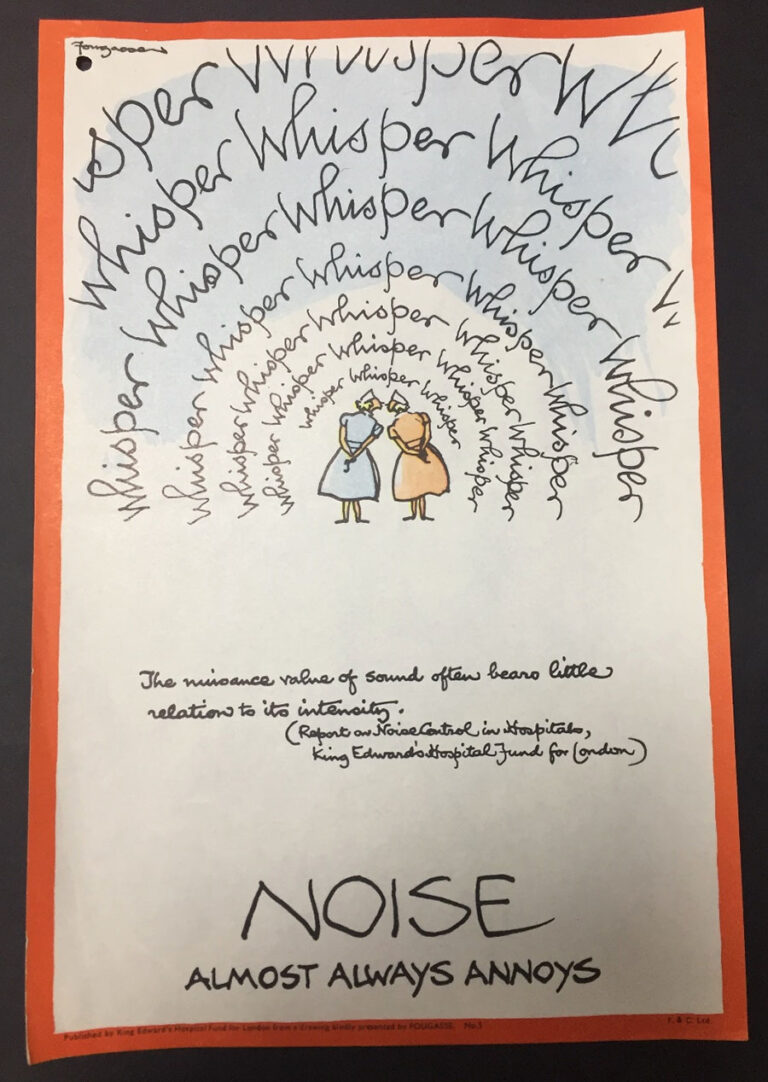

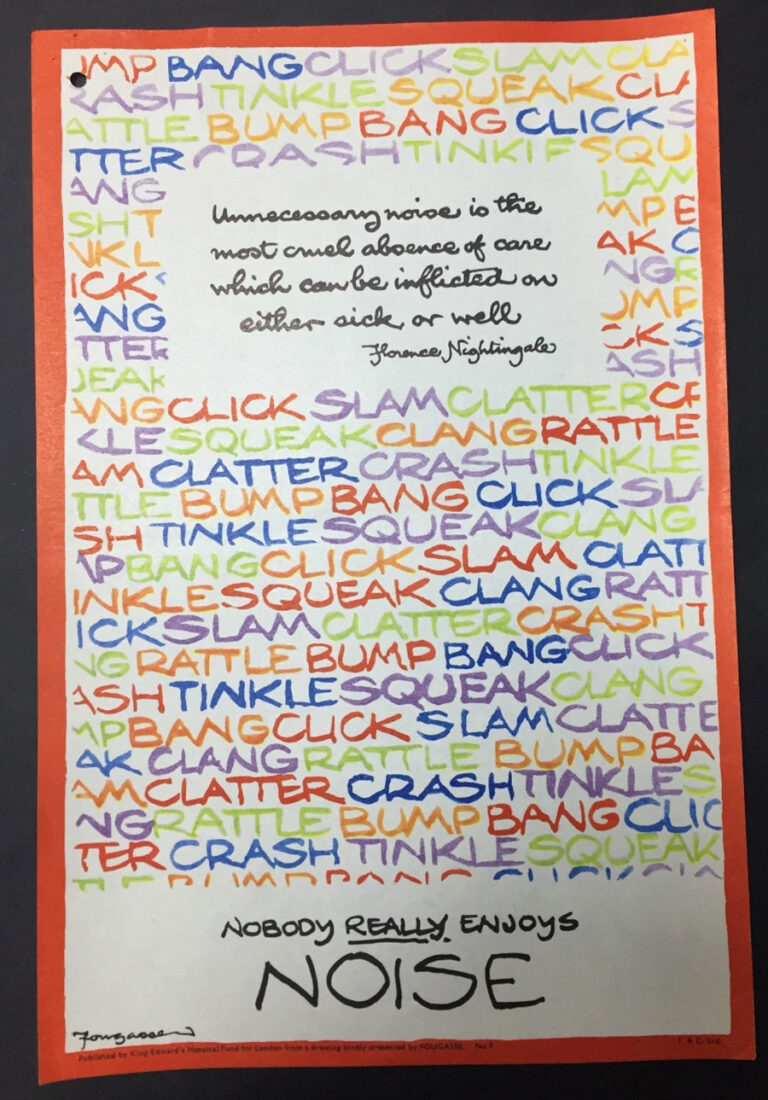

It has long been recognised that noise could be detrimental to health. In the 19th century Florence Nightingale notably said that ‘unnecessary noise is the most cruel absence of care which can be inflicted on either sick or well’. Between 1957 and 1958 the King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London conducted an enquiry into the problem of noise control in hospitals, which was published in a report in November 1958, with a follow-up in 1960.

The enquiry found that ‘the nuisance value of sound often bears little relation to its intensity by scientific measurement’ and identified a number of annoyances in the hospital that could impact a patient’s recovery and welfare, including rattling windows, squeaking wheels, banging doors, tapping shoes, clanking plumbing systems, clattering of cutlery and trolleys, and chattering nurses or patients[ref]‘Noise control in hospitals: A report of an enquiry (1959)’ and ‘Noise control in hospitals: Report of a follow-up enquiry’ (1960) in MH 146/44, The National Archives.[/ref].

![Satirical cartoon image of a hospital scene. Newspaper clipping is from an unknown newspaper found in the file MH 146/44. The patient is falling out of the left-hand side of the bed and the right-hand side of the bed features leering hospital staff. There is a poster on the wall behind the patient’s bed that reads ‘If the hospital noises annoy you – complain. M.O.Health [Ministry of Health]. Patient’s should report: nurses who chatter, nurses without rubber heels, noisy equipment, noisy patients, squeaky parts, loud tv sets.’ There is another poster on the wall that reads “discussions on Berlin by more than two people forbidden’. The caption underneath the image reads ‘You the one who complained to Matron about us making a noise?](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/16141756/noise_1-768x576.jpg)

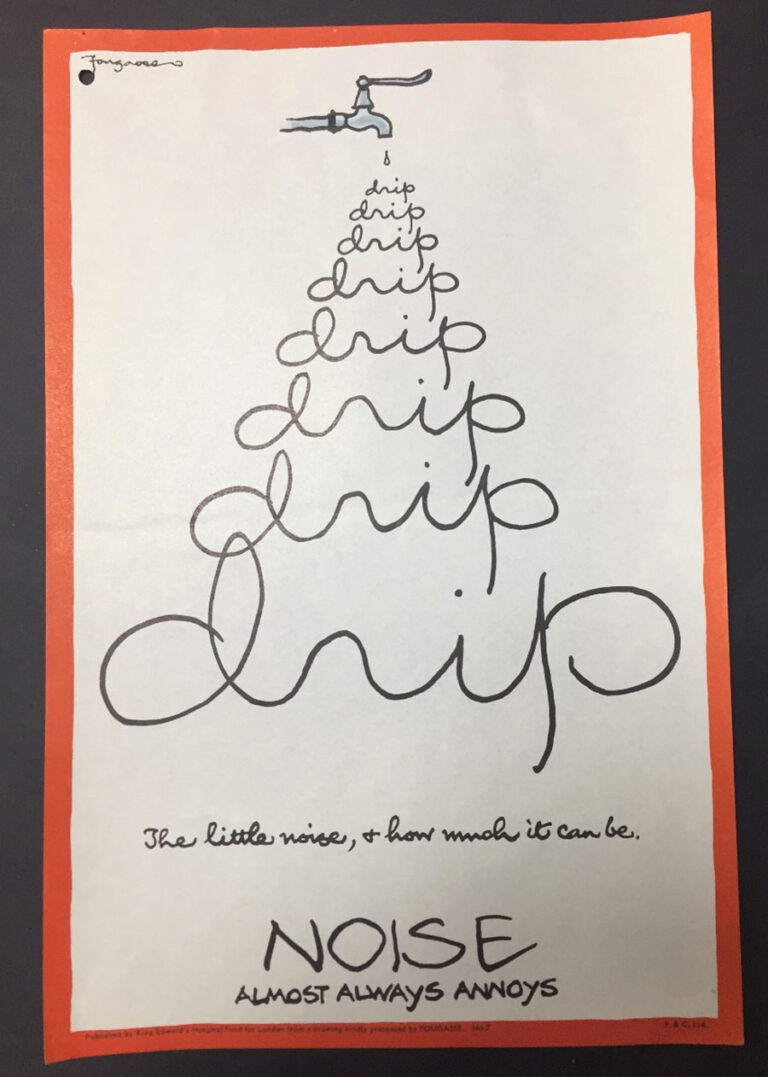

In the aftermath of the report the Fund and the Ministry of Health teamed up to produce anti-noise publicity to draw attention to the issue. Hospitals were sent parcels of eye-catching and memorable posters to display around the hospital. They were drawn by the notable cartoonist Fougasse (born Cyril Kenneth Bird), famous for the wartime poster ‘Careless talk costs lives’. He provided the drawings to the Fund ‘out of the goodness of his heart.[ref]‘Noise Control in Hospitals’, Circular letter to hospitals from R E Peers, Secretary to King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London, May 1962, MH 146/44.[/ref]’

The problem of noise, however, was not restricted to hospitals. Since the 19th century various societies and movements had petitioned the government to bring in legislation to abate noise, such as the Street Noise Abatement Committee and the Quieter London Movement. In 1959 the Noise Abatement Society was established by John Connell OBE, who lobbied to get the Noise Abatement Act through Parliament in 1960.

The Committee on the Problem of Noise

The seriousness of the issue was reflected in the creation of a Committee on the Problem of Noise, set up under the chairmanship of Sir Alan Wilson in 1960. The committee was appointed by Lord Hailsham, the Minister of Science, and co-ordinated by the Ministry of Health to ‘examine the nature, sources and effects of noise, and to advise what further measures can be taken to mitigate it’. The report was published as a white paper in July 1963. Records from the committee, which include the minutes, papers, correspondence and recommendations, are found in the series MH 146.

Noise was defined by the committee as ‘sound which is undesired by the recipient’, noting that, ‘a noise problem must involve people and their feelings, and its assessment is a matter rather of human values and environments rather than precise physical measurement.’

The subjective nature of noise was considered in the report, as it was recognised that many sounds that people might ignore in an urban environment, such as the din of traffic, may cause more disturbance in the countryside and vice versa. It was also noted that the sound of a tap, although a minimal disturbance, could cause extensive annoyance due to repetition.

The subjective experience of noise: Letters from the public

The committee gathered evidence from institutions such as the BBC, representatives of industry such as the National Farmers’ Union, associations of citizens, and other specialist bodies such the British Medical Association. What is interesting here is that the committee also asked for contributions from the public and it’s this correspondence that really drew me to the topic. The following letters can all be found in MH 146/32.

The content of some of the letters, on the surface, can be quite comical, with some people giving the impression of being chronic complainers. Mrs Roots (4 July 1960), for instance, asked that the BBC consider transmitting ‘music recordings of professionals only’, suggesting that the voice be silent ‘until only those with the necessary degree in singing are found?’ Similarly, Mrs Appleton from Southport (20 June 1960) had an array of complaints, from supersonic bangs of planes, yapping dogs, and motor bikes – ending the letter with ‘oh I do wish the poor milkman would keep those bottles quiet at 5:30am.’

However, considering these letters within the context of their time alters how a reader may interpret them. The 1950s and early 1960s saw notable changes to the soundscape of Britain as a result of significant cultural and social changes and changes to consumerism – with increased noises from aircraft and road traffic, new manufacturing processes, and new entertainment sources.

Cars, motorbikes and traffic

The 1950s had seen a growth in motorised vehicles on the road, particularly as car ownership became more attainable for the working class, which led to a boom for the motor industry. The number of registered cars on the road more than doubled by the end of the decade[ref]S Gunn, The history of transport systems in the UK (Government Office for Science, 2018).[/ref]. With this increase there was the need for more efficient road infrastructure, and in 1958 Britain’s first motorway was built – the Preston bypass.

Complaints about noise from motorised vehicles dominates the letters. Mr Trueman of Birmingham (25 June 1960) proclaimed in an impassioned letter,

‘When I had a motor bike in 1912, I got prosecuted for having a noisy silencer & was fined £2 in the law courts, that was 48 years ago. NOW, these young chafes can go about & make as much row as they & NO-BODY says anything. In 1912 a law came out prohibiting motor cycles from producing an offensive and intolerable noise from ‘EXHAUSTS’. WHY ISN’T THIS LAW STILL IN EXISTENCE? … I hope SOMETHING will be done.’

Likewise, an increase in car garages led to Mrs Beadling of Breadon complaining that,

‘We have a garage in the middle of the street and the noise of cars banging and motor cycles roaring it’s nearly enough to drive you up the pole… I damn well hate waking up in the morning.’

Another prominent complaint, which took up a significant portion of the final report, was related to ice-cream vans and their jingles. The ice-cream van was a lot more ubiquitous in the 1960s than today: only a third of households owned a fridge in the early 1960s and by 1970 only 3% of households owned a freezer[ref]’75 Years of Family Food’ timeline, compiled from the Wartime Food Survey, National Food Survey, Expenditure and Food Survey, Family Expenditure Survey, and Family Food Survey. (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, 2015).[/ref]. A letter from a member of the public from County Durham stated that ‘Our chief problem in this area is the problem of Ice Cream Vendors Chimes’, and another complainant claimed the chimes were incessant throughout the day.

Central heating

In June 1960, Ms Foster from Northumberland wrote a heart-felt letter complaining of her sleep disturbance as a result of her neighbour’s central heating, noting the:

‘rolling and bumping noise of water is augmented in the evening and early part of the night by television, as the occupier of the lower flat I suffer from the mechanical noise from the upper.’

This may not seem a great annoyance to the modern ear but considering that, in 1960, only 5% of UK households had central heating[ref]L Kuijer and M Watson, ‘That’s when we started using the living room’: Lessons from a local history of domestic heating in the United Kingdom in Energy Research & Social Science, 28 (2017), pp. 77-85.[/ref] and television ownership had almost doubled since 1956[ref]‘Television ownership in private domestic households’, UCL Social Research Institute, 2019.[/ref], the impact of these sounds can be considered more striking. Foster’s letter shows that a person’s experience of noise should not be trivialised, she continued:

‘… its effect is devitalising … and the roar is terrible to bear.’

The impact of noise on mental health was raised as a concern in multiple letters, including C Bradley (June 1960) from Derbyshire who observed that:

‘Noise is very injurious to the mental health of the community, it impairs one’s capacity in general, particularly when it deprives one of sleep.’

Radio

Evidence submitted by the Woman’s Group on Public Welfare relayed an incident from the summer of 1960, involving a visit to Salisbury Cathedral which was marred by ‘a young couple, hand in hand carrying a small radio playing “pop” music’[ref]‘Memorandum on the Problem of Noise submitted by the Women’s Group on Public Welfare and Sanding Conferences of Women’s Organisations’, 1961, MH 146/135. The National Archives.[/ref]. In the same vein, in a letter from a member of the public (25/6/1960) the complainant wrote:

‘In my opinion, noise from people’s radios, does not need any evidence. It is happening all over the country, the B.B.C. give it out now and then, asking everyone to keep their sets low. Some people put their sets on in the house and sit in the garden in the summer.’

The first portable radio was released in 1954, which led to portable radio sets being used away from domestic settings for the first time, highlighting that experiences of sound were tied up with social and cultural practices.

Aircraft noise

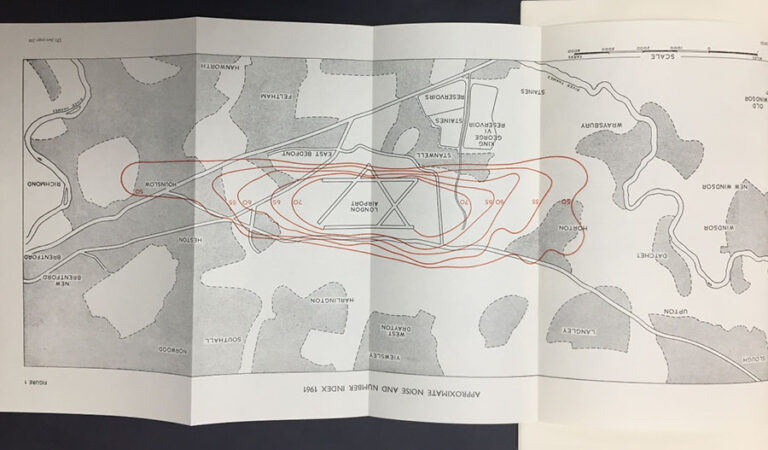

London Airport (later renamed Heathrow in 1966) had opened in 1946 and by the early 1960s it was renowned as an international junction for air travel[ref]‘Our History’ Heathrow Airport, [heathrow.com, accessed November 2020].[/ref]. Mr Beck from Richmond, Surrey (30 June 1960) complained that aircraft plagued the skies in his area from breakfast until 23:45 and that the ‘health of the community is subordinated to the convenience of the aeroplane passenger’.

Were the complaints listened to?

The Committee was for enquiry only and therefore could not advise those who complained, although copies of some of the letters were forwarded on to the Ministry of Housing and Local Government. It was found that noise impacted health by causing stress or disturbing sleep and one recommendation of the committee was to disseminate information to sound technicians to help mitigate noise with insulation.

One member of the public, C Vaughn-Saunders (6 July 1960) suggested creating ‘noise abatement zones’ for:

‘The noisy now own more than enough of this land, and they think where ever they go they can claim the rest. But for all the higher things in life that peace inspires; for the incalculable benefit of its healing qualities both to mind and body, the means must be found of building a wall between the industrial bedlam of modern Britain and what little remains of the sanity of its peace.’

While these zones were never created, these letters offer us some fascinating insight into the soundscape of the 1960s and are an incredible resource for anyone interested in the social and cultural history of modern Britain.

The ‘satirical’ cartoon is by Giles who worked for the Daily Express and Sunday Express newspapers from around 1943 until 1989.

Enormously popular, many of his cartoons were often reprinted in bound annuals.

To add a little to my comment above, the cartoon may date from around 1958 to 1960 as the King’s Fund carried out a series of reports into noise in hospitals.

The initial report appears to have been published in 1958 with follow-ups in 1960 and 1973.

More can be found at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2016/05/careless-talk-costs-lives-noise-hospitals#comments-top

Thank you Richard for this information, I was hoping someone would be able to identify the cartoonist/newspaper!

You are most welcome Dr. Robson-Mainwaring.

Perhaps, given the readership Express newspapers drew on during the 1950s – 1970s, it’s not surprising that nurses and the police often featured prominently in his work for the publications.

A fascinating piece!

Fantastic blog! Really enjoyed it. A fascinating subject in relation to a little considered aspect of mid-C20th social history. Thank you! Sally Middleton.

Aircraft noise was not covered by the Act and in those days aircraft were very loud.

Thank you for an illuminating piece.

I suffer more than enough from the noise that is generated in my area. This consists of sirens (have counted 12 in one day) the aggressive use of the throttle on motorbikes and sudden accelerations of the motor car. I find it hard going to go out into the garden summer or winter without having to listen to this mentally injurious cacophony of sound. It has been a little better during the COVID 19 epidemic. I live near a hospital so the noise must be detrimental to both patients & Staff.

Another problem is sleep (I’m 74) deprivation. The Tennant in the ground floor flat slams doors & bangs a drum at 02.00 a.m. this can happen at any time throughout the day & night. The landlord appears to be impervious to my many complaints.