Chris Heather writes: For more than 10 years volunteers at The National Archives have been cataloguing a series of Home Office Domestic Correspondence dating from the reign of King George III, making the series searchable via Discovery, our catalogue. So far we have covered the period from 1792 to 1805, thanks to our hard-working team.

We are now working on the period from 1806 to 1811, which takes us through Napoleon’s Continental Blockade, the start of the Peninsular War, the construction of Dartmoor Prison, Lord Nelson’s funeral and on through the Regency era with the start of the Luddite disturbances.

All of these events, and other day-to-day occurrences, are recorded in the papers, and we are lucky enough to have an ex-member of Home Office staff volunteering with us. In this blog entry, Carol Kellas contrasts the Home Office of today with that of 200 years ago.

Having worked for 30 years in the Home Office I was very interested to see how, if at all, the preoccupations of the Home Office of the early 19th century chimed with my own experiences from 1975 to 2005.

I felt immediately at home with the 1806 letters. My first job in the Home Office related to the organisation of elections and I felt for those obliged, in December 1806, to deal with the riots at an election in Knaresborough, Yorkshire, during which 200 constables were sworn in, only to be attacked in the streets by rioters. The military were summoned and the Riot Act read.

The cause of the rioting seems to have been attempts by the Duke of Devonshire to put down ‘treating’ [of electors in public houses] and thus keep election expenses down. No doubt this is one of the reasons why the Representation of the People Acts now contain stringent limits on election expenses, although the process of getting the voters out is probably much less fun.

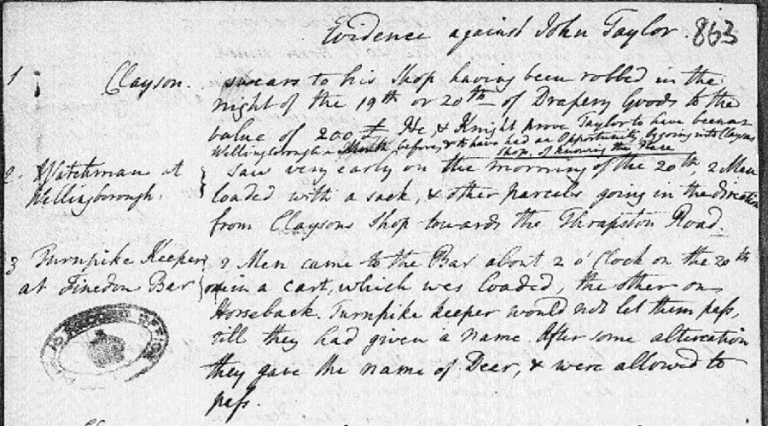

My second posting was in the field of criminal justice. The big difference between then and now is that there was no Crown Prosecution Service in 1806. The victim had to prosecute and this would not have been easy in a small community where the accused would have many friends.

In March 1806 Lord Carysfort was asked to make representations to the Home Secretary in the case of Edmund Forster, convicted of sheep stealing and being held pending execution in Huntingdon jail. The prosecutor, Mr John Earl, a very respectable farmer, was anxious that the sentence be commuted to transportation for life. However, Lord Carysfort did not feel able to recommend this, knowing Forster to be a man of the worst character in every respect. He pointed out that in the neighbouring parishes of Huntingdonshire and Northamptonshire there had been more than 100 cases of sheep stealing in recent years. There was usually no doubt as to the perpetrators, but it had not so far been possible to obtain sufficient evidence to convict. ‘Part of the county’, he says, ‘is infested with a gang of the most abandoned thieves who have managed to escape prosecution through the terror they inspire’.

Even if a victim did manage to secure a conviction, the friends of the convicted person would often draw up a petition for clemency which was taken round all the neighbours for signature.

Often the first name on the list would be that of the prosecutor and one can imagine why they felt pressured to sign. It was not until 1829 that police forces were sufficiently developed to start to take responsibility for prosecutions, and it was not until 1880 that the first Director of Public Prosecutions [Sir John Maule] was appointed. Victims these days often complain that they have not had justice. Their chances would have been far less in 1806.

One advantage of the procedures in those days, however, was the system of rewards and pardons. A victim could offer a reward for information leading to the conviction of a miscreant. They could also ask for a notice to be posted in The Gazette offering a pardon to any accomplice who came forward with information leading to a conviction.

In July 1806 this procedure was invoked in relation to an attack on a watchman, Robert Twyford, who was shot through the body and not expected to survive. A reward of £100 guineas was offered by the Commissioners of the Birmingham Street Acts and a pardon in the usual form was requested. A description of the villain was provided. He was described as being about 5’9’’ tall, about 21 years of age, wearing a light coloured summer coat, white stockings and with a coloured handkerchief around his neck. Of course, the papers do not reveal how often this procedure helped secure a conviction, but I cannot help wondering whether something on these lines might not help today when people see no advantage whatsoever in coming forward to help the police with their enquiries.

The containment and care of prisoners took up several of my working years. In 1806 prisons were not usually seen as the place where a prisoner was to serve his or her sentence. Usually accused persons were held in prison until trial and then, if convicted, sent to the hulks, often awaiting transportation.

The Inspector of Convicts in 1806 was Aaron Graham, who corresponded frequently with the Home Office and made regular inspections of conditions on the hulks. He was particularly keen on issues of diet and health and got the men into the dockyards to work where, apparently, their endeavours were much appreciated.

Graham also had to deal with complaints from prisoners, one of which, in June 1806, related to Thomas Jones who was being held in the Retribution hulk at Woolwich. Jones had been put into irons for refusing to obey an order to work. His case was that, having been a gentleman’s servant, he was unused to work and considered that handling a shovel or pushing a wheelbarrow was too laborious and degrading. Graham said that discipline on the hulks was less severe than he would find in either the army or the navy and the complaint was dismissed.

My focus in the Home Office was on prisoners’ health care and I was pleased to see that prisoners’ diet and health were an issue even in 1806, and that the importance of work for prisoners was recognised. Graham would not have approved of locking prisoners in their cells all day.

Naming ministers to parish vacancies was an 1806 Home Office responsibility, which thankfully no longer exists but issues over pub licences, immigration [the maintenance of French emigres in Jersey], security concerns [French spies allegedly under every bed], disaffection and protest [setting hay ricks alight] were of regular concern in 1806 and continued to keep us busy, albeit in different forms, during my time in the Home Office.

Happily the Home Office had, by 1969, lost responsibility for capital cases, but in July 1806 it had to deal with the case of a Chinese seaman serving on a British East Indian ship who was found guilty of the murder of one of his compatriots. His hanging had to be postponed owing to the tides, and representations were made by Sir William Scott, who wrote from the Old Bailey to say that the other Chinese sailors were very upset about that part of the sentence which said that the hanged man was to be anatomised. Disorder might follow if this was carried out and a riot among the lascars was duly reported in October. The Home Office response was to recommend closer liaison with the East India Company. I am happy to report that ‘closer liaison’ remains a very useful Home Office response to any issue, even in modern times.