The state has long been preoccupied with ideas of ‘decency’. Attempting to protect citizens from committing or being involved in ‘indecent’ practices, it has legislated against them.

Public toilets, being at the same time public and private, have emerged as places where the tension between surveillance and resistance towards the regulation of moral values (and sexuality) has played out.

In this blog, collaborative doctoral student Jessica Gregory shares her research into ‘indecent advertisement’ in public toilets using records held at The National Archives. Jessica’s emerging PhD research focuses on illicit advertisements in the early 20th century.

– Giorgia Tolfo, Collections Researcher, The National Archives

Public toilets – repurposed

From the 19th century, urban centres became sites of increased commercial and leisure activity across all classes. With an ever-increasing number of people wandering down the streets, the use of common privies of local tenements or select facilities of certain shops and railway stations became unsustainable. A new service became more and more necessary: public toilets.

Although strategic efforts had been attempted to provide them before this, through the provision of open-air urinals and lean-to or freestanding iron structures which primarily catered to men, it was only from the 1880s that independent architectural units for both sexes became popular.

Public toilets helped address the scourge of public urination, but it didn’t take long until these started to be used beyond their primary purpose. As semi-private spheres where the hidden and taboo might manifest, they soon became sites of indecency. Inhabiting a space that was at the same time private and public, surveilled and free, public toilets were seen as possible places where aspects of sexuality which were otherwise unacceptable might manifest – like sexual activity between men, or distribution of advertisements for sex related products.

Such activity was deemed beyond the realms of common decency, and to respond to raising concerns, various legislative controls were intended to suppress such ‘indecency’ in public. These included:

- the Offences Against the Persons Act 1861, which criminalised sexual acts between men with sentences of ten years

- the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which made all homosexual acts of ‘gross indecency’ illegal, and

- the Indecent Advertisements Act 1889, which criminalised the display of ‘indecent’ advertisements within public spaces.

Although oppressive and discriminatory legislation was put in place, it was through the police that it was enacted and enforced upon citizens – usually men.

It is mostly through police records that we have a partial picture of which activities might have been deemed ‘indecent’, and what strategies were put in place to catch people involved in them. As the following records and stories demonstrate, while on one side public toilets were heavily targeted and monitored by the authorities as coves of potential illicit activities, on the other side they offered opportunities for resistance against the sexual structures of the era.

‘Indecent’ advertising

One of the primary police concerns about the use of public restrooms was the occurrence of what was considered ‘indecent advertising’. Such advertising typically related to the display and promotion of products that served a sexual purpose.

These advertisements primarily consisted of promotions for products claiming to cure venereal disease or restore sexual vitality, as well as contraceptive products and abortifacient medicines. The open display of such advertisements within public spaces was banned under the Indecent Advertisements Act, including in urinals, but many advertisers tested the limits of the Act by utilising the semi-privacy of the space as a place to promote their contentious wares.

In the 1890s, many advertisement distributors were caught red-handed sticking or leaving their advertisement leaflets or ‘bills’ in public toilets. Police frequently waited around public bathrooms in plain clothes and then followed potential distributors into the toilets to catch them in the act. This was the case for Alfred May, for example, prosecuted in 1890 for posting bills in the urinals of the Star and Garter, Kew Bridge (Middlesex Independent, 1 February 1890).

Several cases resulted in fines and prison sentences, but a Metropolitan Police report from 1890 highlights that efforts to tackle such advertising were not without difficulties. This was illustrated in the case of a man only referred to as ‘Sidney’. Found in possession of bills that were ‘most disgraceful and inexcusable’ (most likely relating to cures for sexual diseases) and intended to be posted in public urinals, he was sentenced to three months hard labour. He appealed the decision. Sidney argued that the bill was a reproduction of an advertisement from a newspaper and therefore that the actions against him were excessive. The Indecent Advertisements Act had not included newspapers within its remit, so Sidney hoped to utilise this loophole in his defence.

In another case within the same report, a man was sentenced to seven days’ hard labour for posting ‘indecent’ bills in urinals, but the court refused to destroy the bills, stating that the action was not specified within the Act (Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/237, 9 April 1890).

The 20th century

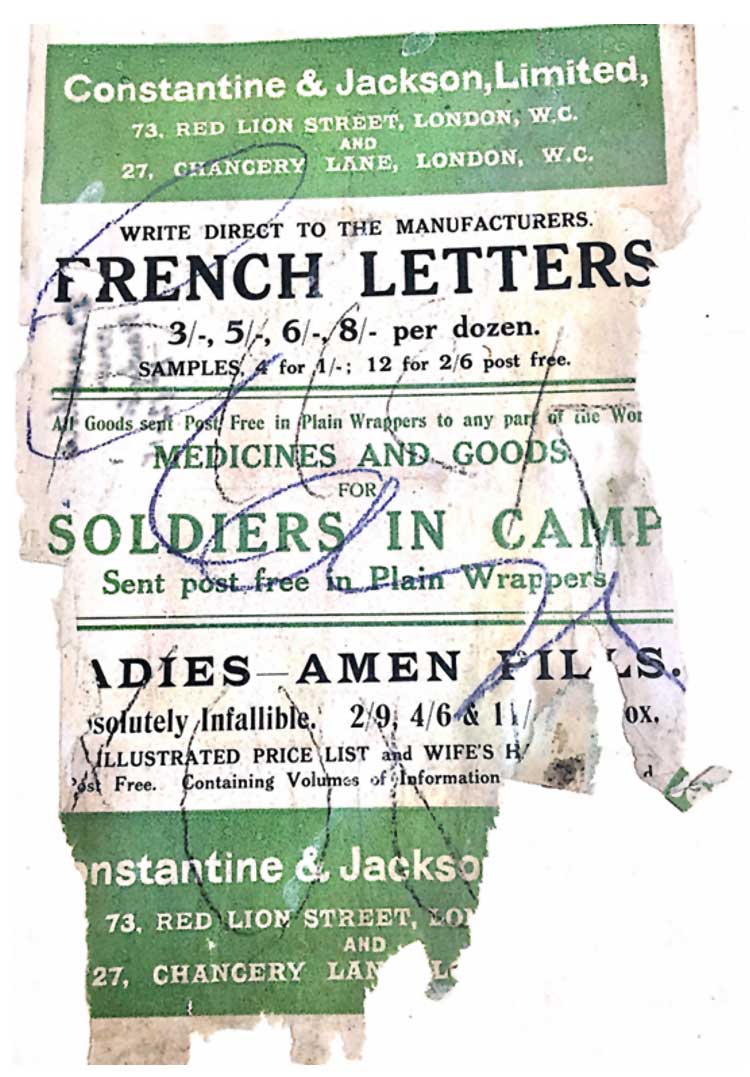

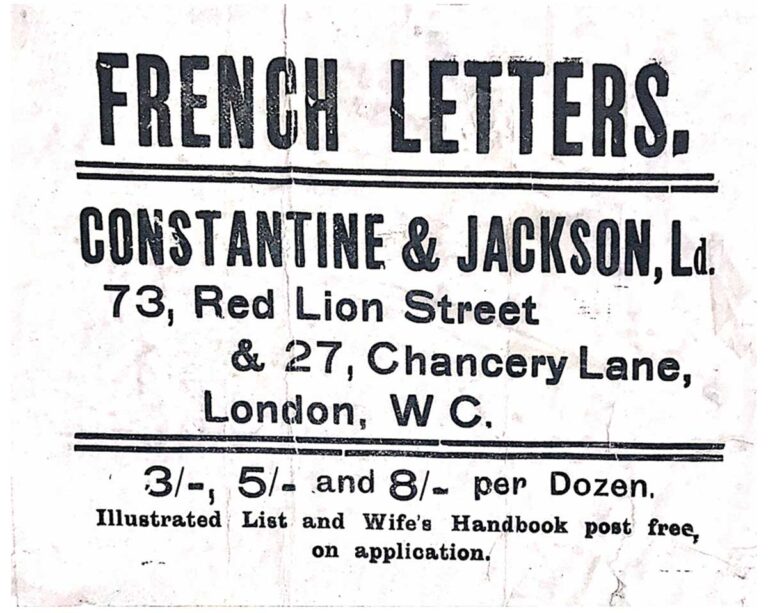

A business called Constantine & Jackson Limited employed billstickering in toilets through the early 20th century. In 1916, two clergymen in St Albans complained about their advertisements for French Letters (condoms) and Ladies Amen Pills (commercially available pills that supposedly induced abortion), saying their ‘indecent’ subject matter would affect ‘the health of the troops’. Constantine & Jackson’s advertisement was ripped down and forwarded to the police for their consideration (Catalogue reference: MEPO 3/937).

Police focused on direct intervention at the point where such advertisements were distributed, and this invariably meant a focus on the person caught at the scene. Constantine and Jackson employed an advertising agent who employed handbillers to disseminate such advertisements. By remaining two steps removed from the actual distribution, the business could avoid easy prosecution. They therefore continued to have their advertisements pasted in bathrooms through the 1910s.

It was only through a more expansive police investigation that the directors of the business were prosecuted in 1919, but this was for handing out their catalogue from their shop. Here at least, direct evidence of their involvement in distributing ‘indecent’ advertisements could be ascertained. They were charged under the Venereal Disease Act 1917 for distributing adverts that promoted commercial cures for venereal disease.

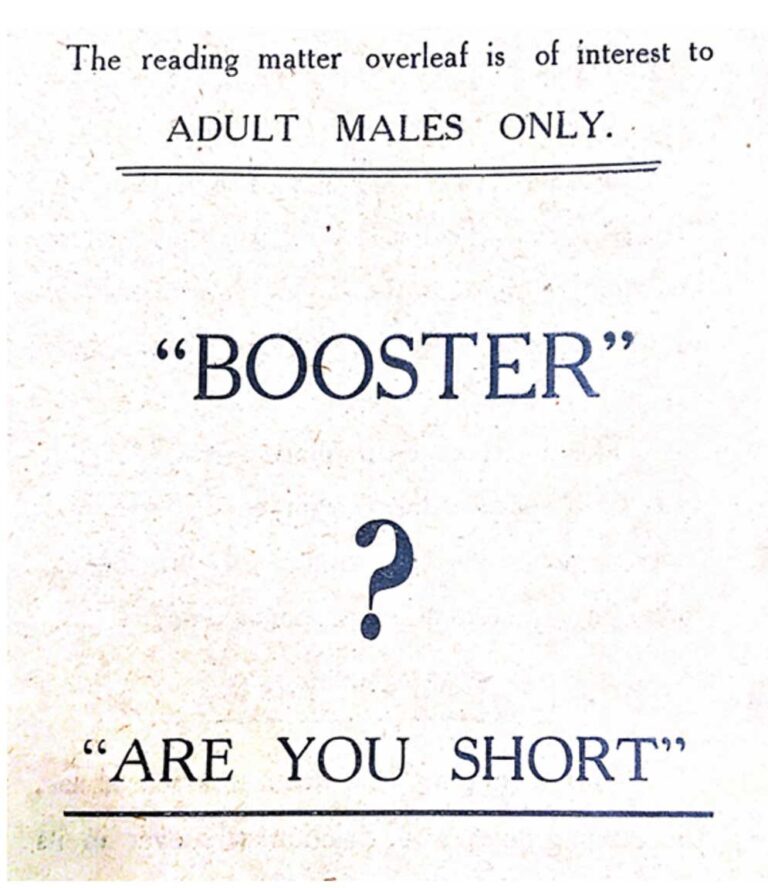

Similar advertisements continued to be found in public bathrooms into the 1930s. In 1935, a man called David Robertson was found leaving leaflets in the lavatories of the Queen’s Hotel, Leicester Square. These toilets were used both by paying guests and the public. The adverts promoted a machine called the ‘Booster’ that claimed to be able to extend the length of a man’s penis. Robertson confessed that these were an invention of his own, that he had been shown something similar by a man in a pub and had decided to create his own business. He promoted them himself, having bills printed and leaving them in places like the hotel bathrooms as well as toilets in public houses (see MEPO 3/934).

Robertson expressed that he had not known such actions were a crime, but descriptions of his guarded actions suggested otherwise. Police statements say that he was sneaking into the bathrooms at regular intervals and avoiding the staff. He was likewise noted as saying that he was very careful about whom he gave them to.

Initial police correspondence explores whether Robertson could be charged under the Vagrancy Act for causing a nuisance in a public place, but the Chief Clerk at Bow Street Police Court thought that the bathroom could not be described as ‘public’. Focus therefore turned to whether the content of the leaflet – with its direct references to sexual anatomy – was criminal, and charges were considered under the Indecent Advertisements Act and the Obscene Publications Act. The court agreed that the advertisement was illegal and ordered that the advertisements and products be destroyed.

Cases such as Robertson’s were rare. Often the various laws meant to address the problem of ‘indecent’ advertising were inadequate when applied to the public bathroom, because of the problems of catching offenders and the issue of whether the bathroom constituted a public space in court. Here the public would continue to encounter ‘indecent’ advertisements, and as much as archival records indicate that many people took offence to such promotions, the persistence and endurance of them suggests that – to at least some of the passing public – such advertising practices inspired them to seek out their products.

The public bathroom acted as a space where authorities sought to control both sanitary and moral cleanliness. This blog has examined how this manifested through actions against ‘indecent’ advertisements, but this was not the only form of indecency that authorities sought to suppress in such spaces. In a related article, Giorgia Tolfo explores the mediation of sexuality itself, through a study of police records on ‘cottaging’ in public bathrooms.

Further reading

Lee Jackson, Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2014)

The article mentions “two clergymen in St Alban’s”. If this is referring to the city of St Albans, then no apostrophe is needed. Otherwise an excellent article.

Thank you for spotting that typo. We’ve corrected it now. We’re glad to hear you enjoyed the post.

Interesting

I’ve been following your blog for quite some time now, and I’m continually impressed by the quality of your content. Your ability to blend information with entertainment is truly commendable.