To help celebrate National Volunteers’ Week, this blog promotes the work of volunteers at The National Archives.

In the early part of the 19th century, the only form of appeal against the severity of a criminal sentence was to petition the monarch for mercy. In practice the petitions were dealt with by the criminal department of the Home Office, with the royal prerogative delegated to the Home Secretary. The petitions and their associated correspondence survive in two large series, HO 17, between 1819 and 1839, and HO 18, from 1839 to 1853, though both series contain correspondence later than those date ranges.

Barry Purdon has been a dedicated volunteer for about 20 years, cataloguing both these series and the predecessor cataloguing project, HO 47, Judge’s Reports. His knowledge and expertise has been invaluable in creating catalogue descriptions for many thousands of petitions.

This blog has been adapted from two articles originally published in the West Middlesex Family History Society Journal.

– Colin Williams, HO 18 project supervisor, The National Archives

I’m one of a small team of volunteers at The National Archives cataloguing series HO18, ‘Criminal Petitions for Mercy’. The Court of Appeal didn’t exist in 1842, so convicted people’s only hope of mitigation of sentence was to petition the Crown whose laws they had broken. Many of these petitions refer to fairly mundane crimes such as pickpocketing and come from all over the country.

However, I have found a stand-out local petition from Hampton Wick concerning Mary Ann Goatley, aged 19, Henry Grover, aged 30 (a gardener from Mortlake), and his wife Martha Grover, aged 31. All three were indicted for ‘burglariously breaking and entering the dwelling house of our Sovereign Lady the Queen’ at Hampton Court Palace [Catalogue reference: HO18/92/31].

In fact the crime occurred at 44 Tennis Court Lane, a grace-and-favour apartment at the palace where Caroline Henrietta Hamilton Sheridan (daughter-in-law of the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan) lived. Goatley was her cook. Sheridan had £30 of silver plate stolen (about £1,800 today) and some silk valued at £20 belonging to Lady Selina Dufferin. Susan Foster (Martha’s mother) was indicted for receiving these stolen items.

At the Old Bailey on 24 October 1842, Goatley and Henry Grover were found guilty of the Sheridan burglary and sentenced to ten years transportation. Foster was acquitted. Judgement on Martha Grover was deferred pending submission of her marriage certificate, confirming that she was legally married to Henry, and a few days later this was produced. ‘For the sake of form’ she was re-indicted to another jury who found that she had been directed by her husband and was therefore acquitted.

A full account of the main trial can be found at Old Bailey Proceedings Online. There is a detailed but less formal report in the Morning Post newspaper of 26 Oct 1842 (available through Findmypast).

Petitions for clemency

The letters of petition refer solely to Mary Ann Goatley. The first is from her father – Henry Goatley, carpenter, of Hampton Wick – and is undersigned by 25 inhabitants of Hampton Wick known to him. These include John Collins, John [Stevens] (Poor Law guardian and employer of Henry Goatley), Job Elphick (butcher), William James (baker), Benjamin Regester (hair draper and Overseer of the Poor), M T Coleman (surgeon), [Edward James] (grocer), [William Hitching] (butcher), Thomas Russell (constable), [Jonathan Fricker] (letter carver), Arthur Sharpe (carpenter), Joseph Heffer (painter), [John James] (cooper), Charles Belchamber (carpenter), James Hill (baker), John Weedon (bootmaker), Thomas Hill (shoemaker), Thomas Powell (late constable) and William Walker (undertaker).

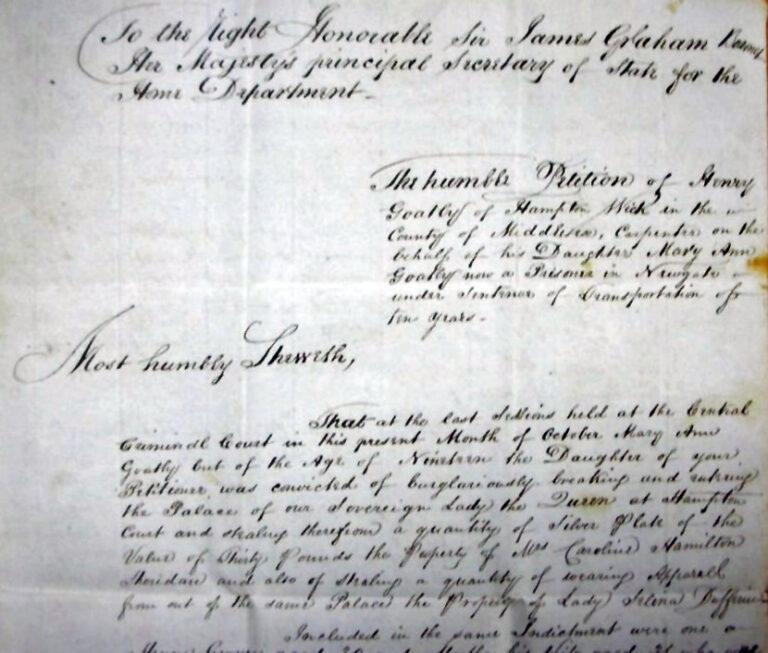

Here is part of the leading page of Henry Goatley’s petition:

Henry Goatley also encloses a letter from Dr Inglis of Lawn House, Hanwell (Mary Ann Goatley’s former employer) who gives her a good character reference. This ties in with the 1841 Census the year previously, which places her in service nearby at Castlebar Hill in Ealing.

The second petition is from a Miss [Caroline] Neave of the Ladies Committee [for prison reform] and is endorsed by Mrs Elizabeth Fry, the well-known prison reformer on that committee. The grounds for clemency for Goatley are that she was lured into the crime by the Grovers, who were much older than she was, combined with her exemplary character prior to this first offence. Additionally, the Ladies Committee considers her to be a suitable candidate for Millbank General Penitentiary rather than being transported.

However, Sir James Graham (Secretary of State for the Home Department), who received the petitions, thought otherwise, and initialled one of the petitions ‘Transport’ and the other ‘Refuse’. Given that it was a first offence with no violence involved, it is unusual for a sentence this severe to be imposed. I suspect that the status of the victims and the location probably had something to do with it and, of course, the fact that it was a substantial burglary.

There is a transcript of the petitions on the website of the Female Convicts Research Centre, and the petitions themselves are available through Findmypast.

Records of transportation

Henry Grover was sent to the convict hulk York at Gosport and then taken to Bermuda, where he is listed on the convict hulk Tenedos in 1847, his wife having unsuccessfully petitioned for mitigation [Catalogue references: HO 19/11, HO 18/194/43].

Mary Ann Goatley was transported on the convict ship Margaret on 5 February 1843, arriving in Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) on 19 July of that year.

A vivid picture of the last three months of Goatley’s voyage to Hobart can be found in the surgeon’s report from the Margaret, as transcribed by Jan Westerink and provided by the Female Convicts Research Centre:

GENERAL REMARKS

The number of Convicts on board the Margaret, at the time of my taking charge in Simon’s Bay [Western Cape, South Africa] amounted to 152, all of whom were landed at Hobart Town. The case of death noted in the Nosological Synopsis was that of a child: another infant also died on the passage, but is not included in that Report, from never having been on the Sick List, as it did not appear to require Surgical Treatment, apparently perishing from defect in the [a?i??ilative] functions. The number of sick was fifty-nine.

The prevailing diseases were affections of the membranes lining the air-passages, Rheumatism and Diarrhoea, arising from change of climate and much exposure to moisture from the Prison Deck and the beds of the Convicts being frequently wetted by leakage…

John [Arnot?] Mould, Surgeon. Hobart Town, August 1st 1843

So, what happened to Goatley thereafter? Following her conviction and transportation, when she arrived in Hobart her prison description (held in the Tasmanian State Archives) was given thus:

Trade: Cook and housemaid

Height (without shoes): 5ft ¼in

Age: 20

Complexion: Fair

Head: Round

Hair: Light Brown

Visage: Small

Forehead: M.S.S. [medium size/small]

Eyebrows: Brown

Eyes: Blue

Nose: M.L. [medium length]

Mouth: M.W. [medium width]

Chin: Small

Native Place: Hampton Wick

Remarks: None

In April 1845 she was given a ‘convict permission to marry’ a widower named Solomon Hill, a free man (ie not a convict). Solomon’s first wife was Sarah Ann Griffiths, who was also a convict and who arrived on the Navarino. He and Sarah had married on 14 November 1842 in Hobart, Solomon then being described as a servant. Just ten months later, Sarah died on 17 Sept 1843, aged 28, having delivered a daughter – Sarah Anne Francis Hill.

Solomon and Mary’s Hobart marriage certificate, dated 23 June 1845, describes him as a boarding house keeper, so it’s not unreasonable to suppose that Mary was assigned to him on arrival from England, given her trade as a cook and housemaid. Did she help Solomon with his then two-year-old daughter?

Mary’s convict record states that on 3 January 1847 she was given permission to remain as proprietress of the Macquarie Hotel, Hobart, but under the surveillance of the Convict Department. We learn that Solomon Hill died almost exactly a year later on 31 January 1848 from an epileptic fit. The death informant in the register is a Stephen Stanley, servant at the Macquarie Hotel. Solomon’s occupation is recorded as hotel keeper although his age is misgiven. Perhaps Solomon had suffered other fits previously and had transferred proprietorship of the hotel to Mary as he was unable to work effectively.

Just eight months later, on 15 September 1848, Mary applied for a second ‘convict permission to marry’, this time to Stephen W Pierce, also a free man. The lieutenant-governor’s approval was gazetted on 27 September 1848 in the Colonial Times and Tasmanian, which also confirms that both parties reside in Hobart and that Mary has a Ticket of Leave (which allows her to work freely within a specified area). The couple wasted no time and married at St George’s Church, Hobart on 3 October 1848. Stephen is named as Stephen Wilson Pierce, timber merchant, aged 27 years, and Mary simply as a widow aged 26 years.

A pardon – and freedom?

On 1 Feb 1849, Mary petitioned for a Conditional Pardon for her crime, which would allow her freedom of movement within the colony. This was recommended by the Governor General on 27 Feb 1849 and her record shows that it was approved on 16 April 1850.

An unsupported ‘fact’ on Ancestry dates her death at 22 May 1850, but a record in the Tasmanian Archives states she was made ‘Free by servitude’ on 24 October 1852. This means she had served her full sentence of ten years’ transportation, having been convicted on 24 October 1842. One presumes this was not a posthumous statement! But it is the final record I’ve found about Mary’s life.

Very interesting story – thank you volunteers!

Wonderful detail

Full of facts, a real insight into the lives of people who through no real fault of their own were dealt with by the upholders of law and order of the land as it was in those hard times. Amazing really that everyone had a ‘trade’ in those days…A fascinating revelation.

What an interesting, and human, story!

Try “alimentative functions” for the *Margaret* surgeon’s report – basically, digestive system.

There is still a lot of material from this era in Tasmanian archives, as yet not digitised nor transcribed. I encourage those interested in this story to keep an open mind to newly available material.

Great stuff