What has a head, a tail, spine, and body, and is covered in short, honey-brown fur?

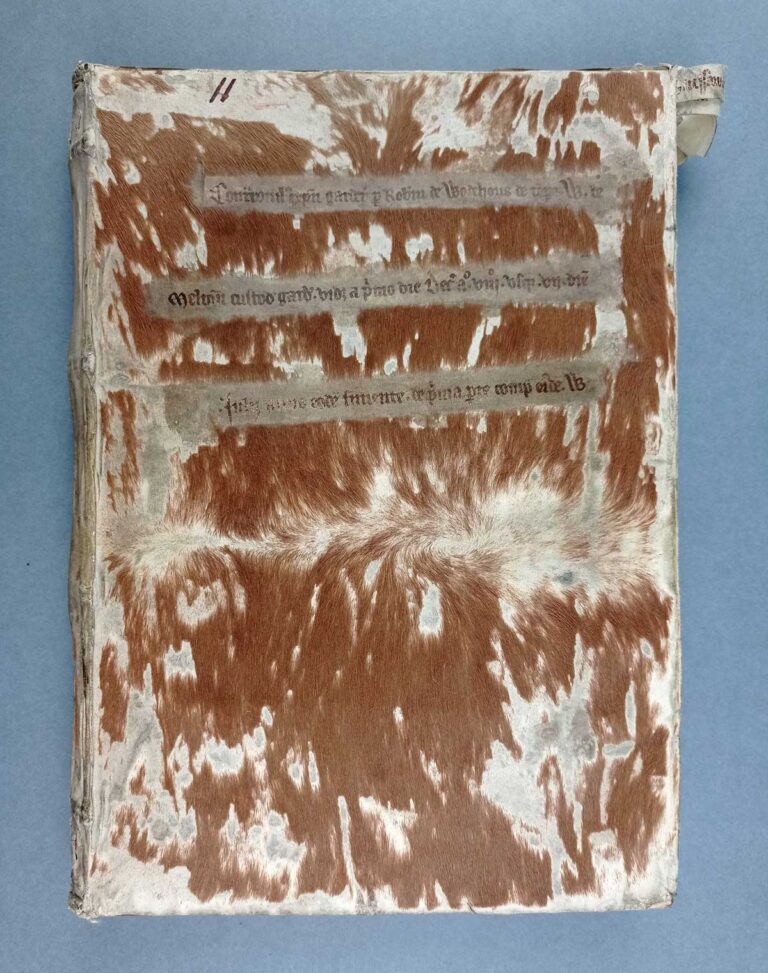

The answer to the question is a little-known treasure found in The National Archives’ Exchequer collection. E 101/376/7 is the Royal Wardrobe and Household account book (1315–1316) of Robert Wodehouse, who was the cofferer (royal treasurer) and comptroller (accounting supervisor) of the Royal Wardrobe – one of the repositories for storing royal regalia and jewellery – from 1309 to 1318.

Books and bound structures are personified by those who work on them every day. In the latest project for my team, Collection Care, we have affectionately dubbed E 101/376/7 ‘the hairy book’. The project aims to compile and describe structural features of our vast limp parchment binding collection.

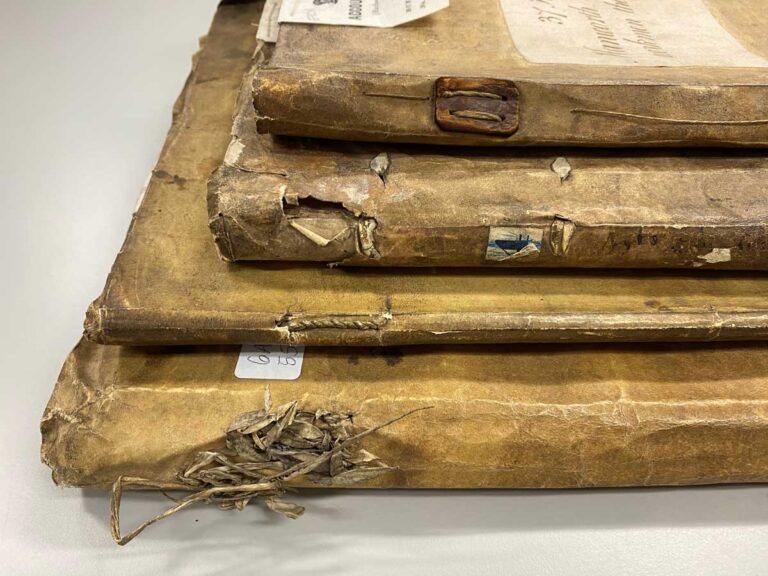

There are many unique features about this book. Besides its obvious hairy appearance, the book is a limp parchment binding – a book bound with a flexible covering material such as parchment and not stiffened by rigid boards. The body, or bookblock, made up of folded or single groups of paper or parchment, can be attached directly to the cover via thin parchment strips, or sewn onto strips of skin and attached to the cover separately.

There are multiple methods of construction, but the main characteristic of the limp parchment binding is its ability to open flat, allowing for the ease of writing. A flat writing surface made this type of binding a popular structure for account books, ledgers, and journals. As such, they are also referred to as stationery bindings.

Wodehouse’s account book is unique as it contains many features typical of an early medieval account book, from its limp covers, as previously mentioned, to its envelope fore-edge flap, but also sports some other less common English limp parchment binding characteristics.

The book’s materiality

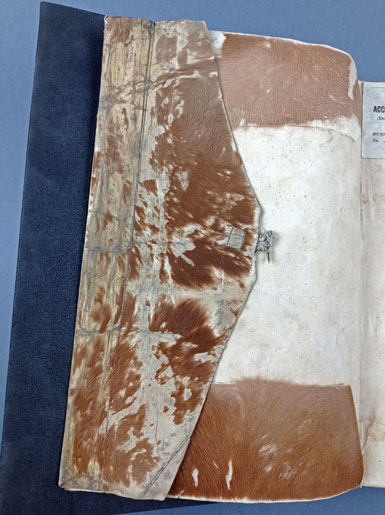

Firstly, let us begin with the showstopper feature: the covering material. The covers are constructed from what is referred to as ‘hair vellum’: a parchment processed in a particular way that allows for the skin to maintain its hair.

Hair vellum bindings, particularly on stationery bindings, are rare. Not much is known on the exact production processes, or why makers used limp parchment binding covers instead of the traditional, fully processed parchment. Preliminary research shows hair vellum is mostly found on 14th-century bindings from The National Archives’ Exchequer English-Bordeaux accounts. Robert Wodehouse’s Royal Wardrobe account book is one of two exceptions, the other being the account book of Gilbert de Bromleigh, the king’s clerk in Carlisle (Catalogue ref: E 101/14/22, 1311), for the army, navy, and ordnance department.

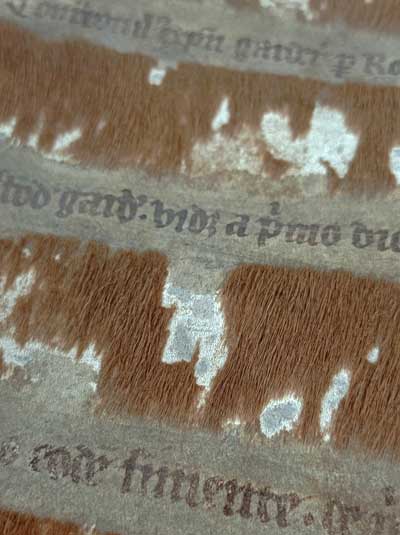

Visually assessing bindings and their materials can provide the conservator with information on the bindings’ structures, as well as the animals used for the bindings’ construction. Animals have distinctive hair follicle patterns and with visual analysis, the hair follicles and growth pattern of the hair on the account book’s covering material indicate that calf skin was most likely the animal of choice. A concerted effort was made to cleanly shave away a series of three rows on the left cover to display iron gall ink manuscript text (see closeup image), showing that maintaining the hairiness was an important aesthetic element to the binding.

The book’s construction

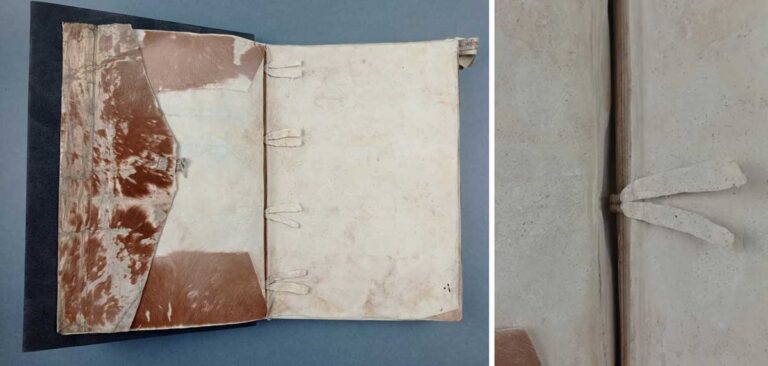

The stationery binding is one of functionality and, despite its many variations, was created with the book’s everyday use in mind. Wodehouse’s account book is constructed in two parts: the bookblock, and its cover, that rely on a secondary form of attachment. The bookblock is sewn on a series of alum-tawed skin strips called sewing supports that were left un-cut, possibly to allow for the addition of more blank pages if necessary.

We did not immediately identify the bookblock-to-cover attachment, as there were no tell-tale signs on the exterior of the cover. By examining below the interior folds of the cover, and following the paths of threads throughout the bookblock, however, we revealed a series of possible attachment methods.

The first and last sheets of the bookblock, known as flyleaves, were tucked below the inner folded edges of the covering material. This provided a temporary form of attachment, as the sewing supports could be easily accessed if the folded cover edges and flyleaves were lifted.

On this account book, structures known as endbands provide another form of attachment. Whilst serving both a structural and decorative purpose here, the endband, based on other English stationery bindings in The National Archives, is not a commonly found feature on these bindings during this period.

An endband is sewn on both the head and tail ends of the bookblock and spine, with a series of different coloured threads visible at the heads of the woven structures. The design pattern most closely resembles that of a herringbone pattern (as shown in the right-hand image above) commonly found on non-stationery bindings of that time and earlier.

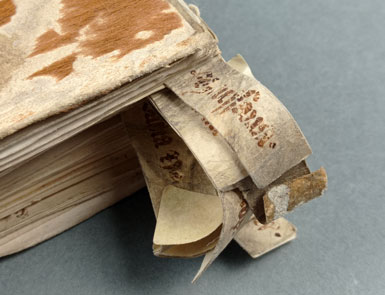

Account books covered a specific length of time. To assist in the organization of information and for the ease of referencing, parchment index tabs were added to the bookblock’s fore-edge.

The tabs extended well past the bookblock, and their length, coupled with the envelope fore-edge flap, caused the tabs to fold and curl. Interestingly, we know this happened long before the account book became part of The National Archives’ collection, as historic repair parchment is visible. Additional pieces of parchment were used to support or extend the original tabs.

A common feature of the limp parchment stationery binding is the fore-edge flap and some form of fastening.

Depending on which cover the flap extends, it can provide clues as to where the binding was constructed. Historically, fore-edge flaps extending from the right cover, with the fastening point on the left or ‘front’ of the book, were traditionally an Italian feature, versus those extending from the left cover being English.

Wodehouse’s account book features an envelope fore-edge flap extending from the left cover, allowing for it to be wrapped over the bookblock fore-edge onto the right cover. The fore-edge flap was secured by a tie. We can see evidence of this, with a piece of the alum-tawed skin tie laced into the tip of the flap remaining.

The Limp Parchment Binding Project

The limp parchment binding collection at The National Archives spans multiple centuries, offering decades of valuable information on stationery binding practices and techniques. In the late nineties to early 2000s, a survey was undertaken to document the most interesting features of these bindings at the time.

The survey was re-imagined 20 years later to include as much data on the bindings as possible in a digital format that would allow for more comprehensive and searchable results. Over the course of six months in 2022, a team of two young adults from the KickStart initiative surveyed approximately 300 bindings, documenting the materiality and structural elements found in this unique collection, hair vellum bindings included.

The data collected from this survey will eventually be uploaded to our Collection Care team’s documentation and knowledge base system, ResearchSpace, providing the opportunity for wider dissemination of the survey’s results.

The survey has become a catalyst for further explorations into the limp parchment binding structure, such as the survey’s development in ResearchSpace itself. We hope that the form in ResearchSpace will eventually be used to record survey data on other limp parchment bindings in European archives’ collections. The documentation of these bindings, with the use of ResearchSpace, will provide a huge repository of data that can be analysed, visualised, and disseminated in the form of knowledge maps portraying links and trends found between objects, collections and all those involved in the objects’ histories.

The documentation of the various features and characteristics of these bindings, with The National Archives’ collection at the heart, will shed light on the multiple techniques, structures and trends found in English medieval account books. Perhaps it will answer the question as to why hair vellum was used on Robert Wodehouse’s Royal Wardrobe and Household account book.