The ‘Great Train Robbery’, which occurred 50 years ago on 8 August 1963, has been labelled the ‘crime of the century’. A gang of thieves held up the Glasgow to London Travelling Post Office train and stole £2.6 million in used bank notes (around £50 million in today’s money). The robbers ambushed the train at Sears Crossing near Cheddington in Buckinghamshire, and then ‘holed up’ at Leatherslade Farm near Oakley. The heist was carried out with a degree of precision bordering on the military, but it all quickly unravelled for the thieves – by January 1964 there were 12 men on trial, and others on the run. Several of those found guilty received heavy sentences (30 years in some cases), and this sparked off a national debate about the fairness of the punishments administered, in relation to other types of crime.

Casualties of the raid

The crime captured the British public’s imagination (£2.6 million was an absolutely staggering amount of money in 1963) and has remained high in the national consciousness ever since, but it is has never been forgotten that this was not a ‘victimless crime’ (that phrase is definitely an oxymoron!); Jack Mills, the driver of the train, received head injuries during the raid, and it was also a traumatic experience for the fireman, David Whitby, and the Post Office staff on board the train (force was used by the gang to break into the ‘High Value Package’ coach, where the banknotes were stored).

Value of primary sources

Over the years there have been many newspapers articles, books and films about the ‘Great Train Robbery’. Various myths and falsehoods have developed about this notorious event. In recent years several (previously closed) documents concerning the robbery have been made available at The National Archives as the result of Freedom of Information requests and historians have been drawing on these primary sources, recognising their value in revealing certain details. However, even though these records give a fuller picture, several questions remain unanswered about precisely ‘who had done what’ during the heist.

Striking images

The photographs held by The National Archives concerning the robbery are particularly striking. Some of them tell us a great deal about social history. In this first example we see the signal at Sears Crossing that was used to halt the mail train, and the battery that was used to turn on the red light (a glove was used to mask the green light).

The signal that halted the mail train HO 287/1496 (1)

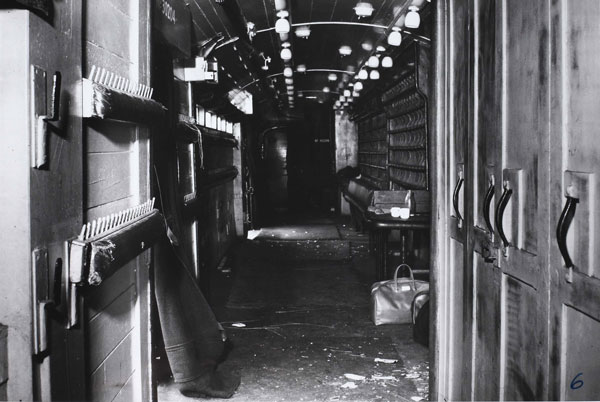

In the photograph below we see the interior of the ‘High Value Package’ Coach, left bare after the raid:

The interior of the 'High Value Package' Coach - HO 287/1496 (6)

Next we see a view of Leatherslade Farm, the robbers’ hideout:

Rear view of Leatherslade Farm - HO 287/1496 (9)

The Buckinghamshire Police discovered the hideout on 13 August and documented everything thoroughly. The image of the kitchen at Leatherslade Farm gives a real insight into ’60s interior designs:

Kitchen at Leatherslade Farm - HO 287/1496 (26)

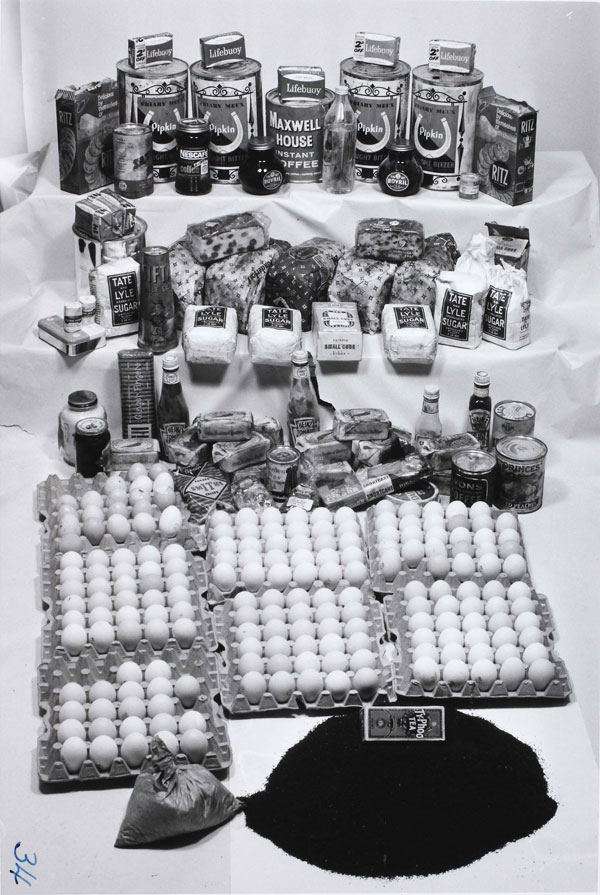

The police were surprised to find how well-stocked the larder was. Peter Gutteridge has written that ‘the food inventory the police later made is a snapshot of working-class eating habits of the time’. There was a large amount of tinned food, including luncheon meat, corned beef, and baked beans.

Foodstuffs found at Leatherslade Farm - HO 287/1496 (34)

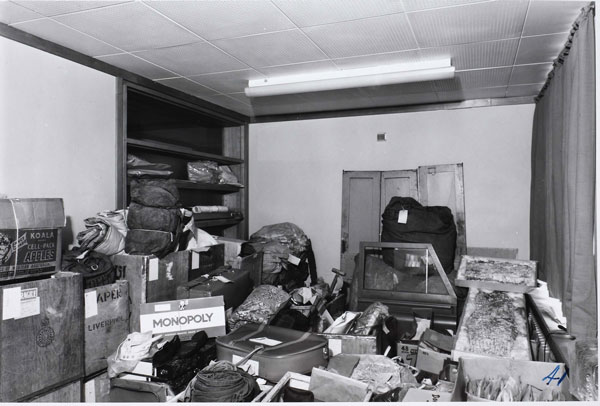

The final photograph to be highlighted here is the exhibits room at the 1964 court trial (held at Aylesbury) of those accused of the robbery, featuring the Monopoly set used by several of the gang, who had played the game using real money to pass the time at Leatherslade Farm – the cards were a good source of fingerprints for the police.

The exhibits room for the Court trial of 1964 - HO 287/1496 (41)

Timetable of a crime

As mentioned, many books have been published about the Great Train Robbery, and one aspect I’ve noticed is that writers on this subject are meticulous in noting the exact times that the Travelling Post Office (TPO – as trains carrying mail were known) left Glasgow on the evening of 7 August, the times and locations where extra coaches were added, and finally, the time that the train came to a stop (3.03 am) before the Sears Crossing home signal as it showed red – a type of ‘historical trainspotting’. Of course, a good deal of the fascination with this subject is that the target of the crime was a train, bringing to mind the exploits of Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch gang in the American Old West.

‘Railways Change Lives’

Moving away from the theme of crime, but remaining with the subject of railways, The National Archives, in partnership with the National Railway Museum, is holding a one-day conference at Kew entitled ‘Railways Change Lives’ on 7 September. You can find out more about this exciting event – there are still a few places left, so don’t delay if you wish to book a place!

Further reading

The Great Train Robbery: The Untold Story from the Closed Investigation Files, Andrew Cook (The History Press, 2013)

The Great Train Robbery, Peter Gutteridge (The National Archives, 2008)

The Great Train Robbery: A New History, Jim Morris (Amberley, 2013)

The Great Train Robbery: Crime of the Century: The Definitive Account, Nick Russell-Pavier & Stewart Richards (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2012)

One should not forget the large amount of lavatory paper that was also found at the hideout. It is regrettable that some of the records are still closed and that Discovery still makes it difficult to trace the individuals involved (i.e. “and others”) as well as “Reynolds B.R”. rather than his full name.

One of the issues at the time was that there was no definite estimate of how much money was on board and the authorities’ lax attitudes to the carriage of the banknotes. The T.P.O. ceased in 2004.

The talk ‘Railways Changes Lives’ is also at the National Railway Museum in York and it is regrettable that in a time of austerity that the cost of the talk is high.

My fathers van was stolen from Guilden Morden in 1963 and was found by police at

Leatherslade Farm used on the great train robbery, how can i find out what happened to the van.

Not sure of make of van, it was black and had a small plastic bunch of flowers stuck on the dash

Hi Ray, thanks for your comment.

To investigate your enquiry you (or a researcher acting on your behalf) would need to consult the original files concerning the Great Train Robbery which have not been digitised. Unfortunately there is no access to original files held by The National Archives due to the ongoing Coronavirus crisis, so you cannot make progress with this at present. Our website will be kept updated regarding our services.

I expect that the van is mentioned in the files as part of the investigation but I rather doubt that you would find information about the fate of the van after it was found by the police, that is a level of detail which you would probably not find in the files that have been selected for permanent preservation.

My father, Jack Parker, supplied the vehicles that were used for the GTR. He had a company based out of Mullards Yard, in Edgware, using an old engine shed left over after the station closed on the closed route to Milll Hill. He bought, sold and refurbished old Army Vehicles!

He was visited one Saturday morning, and provided the Bedford and Austin ex MOD Vehicles, ostensibly for a fruit and veg shop. He was arrested as part of the enquiry and released once he proved his innocence!