When you look at it today, the phrase ‘for all the tea in China’ seems a little odd. The three most popular black teas all originate from South East Asia, with Darjeeling, Assam and Ceylon being the most well-known. But back in the middle of the 19th century it was a very different story. Those teas had yet to become popular, and it was instead the Chinese teas which were heavily imported, including Congou, Keemun and Oolong.

The Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing), signed in August 1842, opened up four ports in China to foreign trade – Amoy (Xiamen), Foochow (Fuzhou), Ningpo (Ningbo) and Shanghai, as well as Hong Kong, which was ceded as a crown colony. The export of Chinese teas soon became a very popular and valuable commodity, particularly to the British market. Competition to bring back the first pickings of the season grew rapidly, eventually developing into a race.

In 1854 the first international race was recorded which involved just two competitors – the clipper ships Chrysolite and Celestial. On 14 July 1854, Chrysolite sailed from Foochow and Celestial from Whampoa, with the Chrysolite arriving at Deal after 108 days, one day ahead of Celestial. To spice up the competition, an additional payment of 10 shillings per ton was allotted to the owner of the cargo of the first ship arriving in dock.

By 1866 the competition had grown considerably, and the fastest and newest clipper ships assembled in Foochow in May to begin loading tea chests for the journey. From the lists of shipping in port, printed in the Foochow Advertiser, we can put together the details of the competitors. The following are the names of the nine ships, their owners and commanders, their tonnage, the ports where they were built, and the respective departure dates:

The race however, was between the five ships which left in May – Fiery Cross, Ariel, Taeping, Serica and Taitsing. Clippers leaving in June were not serious contenders and would not have stood much of a chance of catching the front runners

| Name | Tonnage | Captains | Where built | Year built | Official no. | Port of registry | Owners | Left Foochow |

| Ada | 686 | Jones | Aberdeen | 1865 | 54577 | London | Wade & Co | June 6 |

| Ariel | 853 | Keay | Greenock | 1865 | 52743 | London | Shaw & Lowther | May 30 |

| Black Prince | 750 | Inglis | Aberdeen | 1863 | 48501 | London | Findlay & Co | June 3 |

| Chinaman | 668 | Downie | Greenock | 1865 | 52676 | London | Park Brothers | June 5 |

| Fiery Cross | 689 | Robinson | Liverpool | 1861 | 29165 | Liverpool | J Campbell | May 29 |

| Flying Spur | 731 | Ryrie | Aberdeen | 1860 | 29004 | London | Robertson & Co | June 5 |

| Serica | 708 | Innes | Greenock | 1863 | 45261 | Greenock | Findlay & Co | May 30 |

| Taeping | 767 | McKinnon | Greenock | 1864 | 47842 | Greenock | Roger & Co | May 30 |

| Taitsing | 815 | Nutsford | Glasgow | 1864 | 49555 | Greenock | Findlay & Co | May 31 |

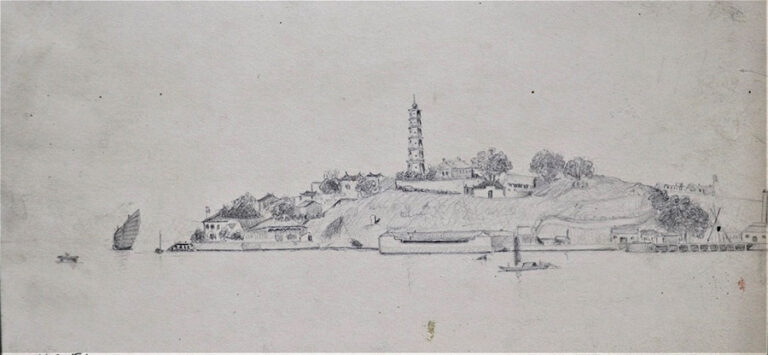

The loading took place at the Pagoda Anchorage, at the heart of the tea district. Every spare inch of space would be used up to carry as much as possible of the precious cargo. Taeping was loaded with 1,108,709 lbs of tea; Ariel, 1,230,900 lbs; Serica, 954.236 lbs; Fiery Cross, 854,230 lbs and Taitaing, 1,093,130 lbs.

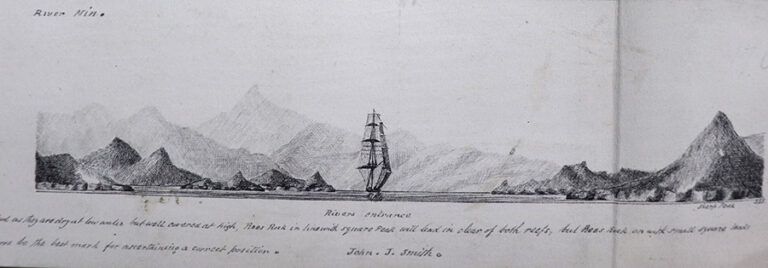

From the anchorage the ships had to be towed down the River Min and across the tidal breakwater and to the open sea.

The competitors

Fiery Cross was built 1861, which made it one of the oldest clippers in the competition, but it was also the most successful, having won the race four times, in 1861, 1862, 1863 and 1865. The ship was constructed by Chaloner of Liverpool. It was the lightest ship at 689 tons, although this was not always an advantage. Many of the clipper ships carried ballast such as lead or iron weights to make the boat sit lower in the water and to increase stability and weight distribution.

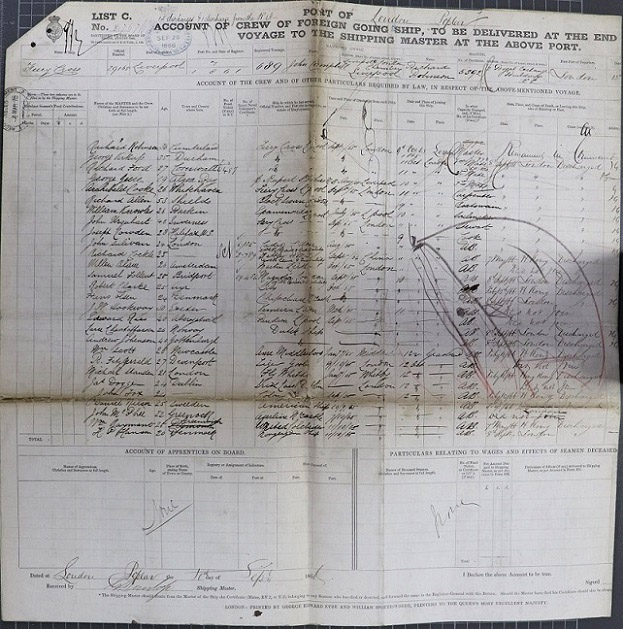

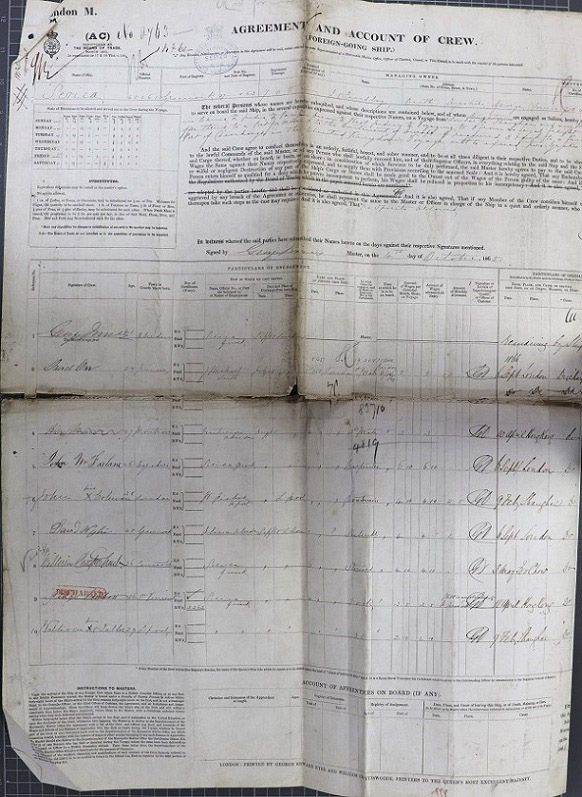

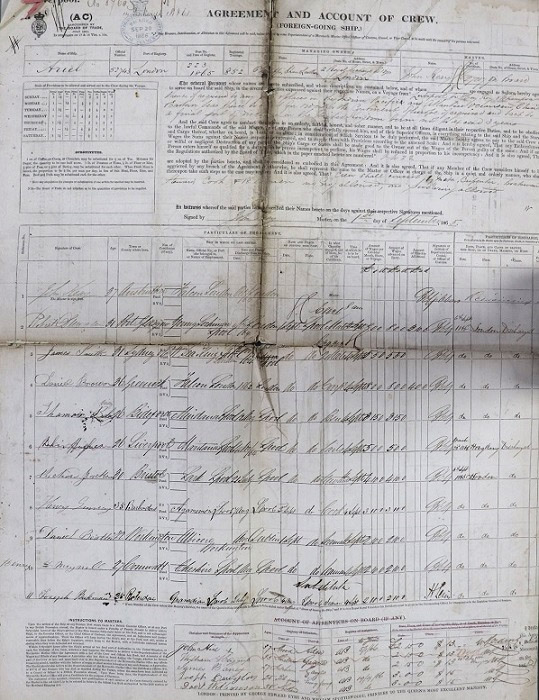

The Master of the Fiery Cross was Richard Robinson, aged 30, from Seaton in Cumberland. An experienced sailor, he first went to sea as an apprentice in 1844 and qualified as Master in 1854. Fiery Cross sailed from Foochow with a full complement of 32 crewmen. 13 of the outgoing crew on the voyage from London were discharged at Hong Kong, and as a result Robinson took on 12 men at Hong Kong, including nine able seamen, and one at Foochow.

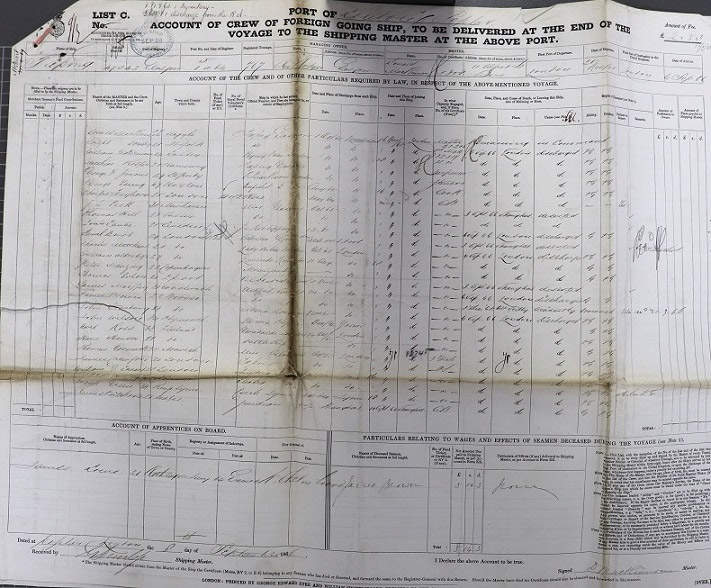

Serica was built in 1863, and won the competition on its first attempt in 1864. The ship was constructed by Robert Steele of Greenock, and was heavier than Fiery Cross, weighing in at 707 tons. George Innes, the ship’s master, was the oldest of the captains, and was born in Aberdeen in 1824. He first went to sea as apprentice in 1839 and was issued with his Master’s certificate in 1852.

Serica sailed from Foochow with a full complement of 32 crewmen. 5 able seamen had earlier been discharged and replaced at Shanghai in February 1866, and 16 crew were discharged and replaced at Hong Kong in April, including the 3rd Mate and the Cook. A crew of 32 allowed for two watches of 14 sailors to be on duty at any time, with a reserve of four crew who could be used at any time.

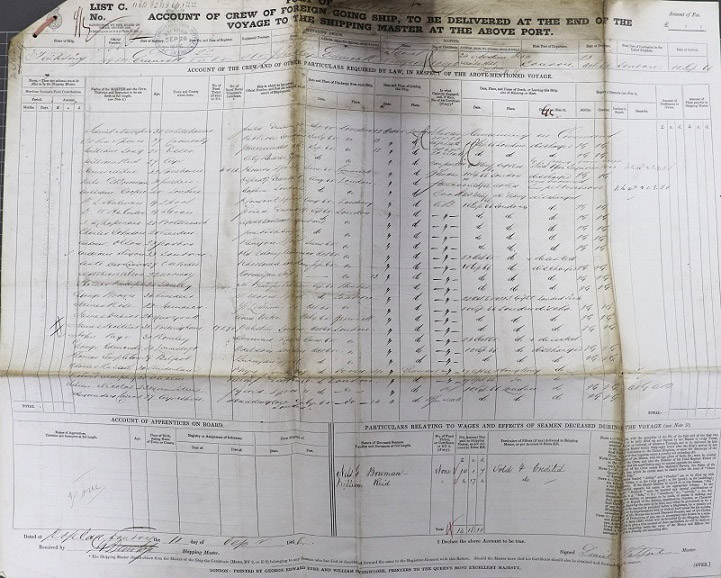

Taeping was an even more recent clipper, built in 1864 by Robert Steele of Greenock, and was slightly heavier, at 767 tons. The Master, Donald McKinnon, was born on the island of Tiree, in Argyllshire, in 1828. He first went to sea as an apprentice in 1843, and obtained his Master’s certificate in 1851. McKinnon had also qualified as a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve in 1854, making him the only master of the main competitors who could use the term Commander. His RNR service record, which is held in the series ADM 240, describes him as 5ft 5 in tall, with brown hair, blue eyes, and a scar on his nose.

Taeping had commenced its outward voyage from London on 20 November 1865 with only 26 crewmen. It sailed from Foochow with 27 crew, as four able seamen deserted at Shanghai on 3 April 1866 and they were replaced at Shanghai on 10 April with a further seaman taken on at Amoy on 21 April. This made it short of its complement by five crew, but that would not hamper its performance; it merely meant that the remaining seamen had to work even harder.

Taitsing, which was also built 1864, was constructed by Connell of Glasgow, and was heavier still, at 815 tons. It was taking part in its first tea race from Foochow. Taitsing’s Master, Daniel Nutsford, was born in Whitehaven, Cumberland on 6 June 1835, making him the youngest of the Captains in the race. He first went to sea as an apprentice in 1852, and was only issued with a Master’s certificate in October 1865, one month before the outward voyage from London. But he still brought with him a lot of experience at sea, and had qualified as 2nd Mate in 1858. He was very well chosen for this particular voyage, as he had made it four times before, twice on the Fiery Cross and twice on the Serica. Nutsford had served as 2nd Mate on Fiery Cross between December 1861 and September 1863, and as 1st Mate on Serica between November 1863 and September 1865.

Taitsing’s outward voyage commenced from London on 23 October 1865. Able seaman George Brown was landed sick on the Isle of Wight, only five days into the voyage, on 28 October, and the Carpenter, William Reid, died after falling from the main mast when making repairs on 9 November 1865. Additionally, Steward, Niels G Bowman, from Sweden, jumped overboard when at sea on 10 March 1866 and drowned. The Carpenter was replaced at Hong Kong on 17 February 1866, and the Steward was replaced on 20 April along with the Cook and four able seamen. On 11 May 1866, shortly before Taitsing was due to leave Foochow, the Master was also obliged to take back as a passenger Alfred Brunton, the Master of the Young Lochinvar, a ship which had earlier run aground near the entrance to the Min River, off Foochow.

Ariel was the newest ship of the five built 1865 of Iron-Wood composite, and was the heaviest, at 852 tons. Like Serica and Taeping, Ariel was constructed by Robert Steele of Greenock. Although it was on its first run, Ariel had a very experienced Master. John Keay was born in Anstruther, Fife, in 1828, and first went to sea as apprentice in 1843. He obtained his Master’s certificate in 1853.

Ariel’s outward voyage commenced from Liverpool on 4 September 1865. The clipper left Foochow with a full complement of 32 crew, including Ordinary Seaman Charles Gifford, formerly of the Young Lochinvar, who was working his passage home, and so received no pay.

The voyage home

Unfortunately, while crew lists and agreements and log books survive for all of the five main competitors, they tell us very little about the voyage itself, recording instead, as required by law, the full details of the crew, their contracts and rates of pay, and only basic details of the voyage such as departure and arrival. However, there was considerable interest in the race, and details of progress was telegraphed to Lloyd’s at various staging points and released to the press. Readers were kept up to date in articles and in the shipping sections of newspapers such as the Pall Mall Gazette and the Times, from which this narrative is drawn.

Fiery Cross obtained a start of one day over the others, departing on 29 May. Serica, Ariel and Taeping crossed the bar of Foochow in company together on 30 May. Taitsing started the following day.

Fiery Cross followed the prevailing winds, which took them to the Paracel islands, in the South China Sea, on 3 June. Serica, Ariel and Taeping met with similar weather. Fiery Cross saw nothing of them until 7 June when she passed Ariel on the opposite tack. The next sighting point was at Anjer, in the Strait between Java and Sumatra. Fiery Cross passed the lighthouse at Anjer on 18 June, Ariel and Taeping on 20 June, and Serica and Taitsing on 22 June. So by this stage Fiery Cross had a two-day lead over Ariel and Taeping. Taitsing had caught up on Serica and both ships were a further two days behind. Fiery Cross passed Mauritius on 30 June and Ariel followed suit on 2 July. On 15 July Fiery Cross rounded the Cape of Good Hope, still in the lead, with Ariel a day behind and Serica a full week behind.

On 9 August Taeping had caught up with Fiery Cross, and the two sailed together until 17 August, when Taeping took advantage of a westerly breeze to move out of sight of its rival, which was becalmed and barely moving for the next 24 hours. On the morning of 6 September Fiery Cross passed the Isle of Wight, unaware of the location of its rivals and its position in the race. As it turned out the lull had made a considerable difference.

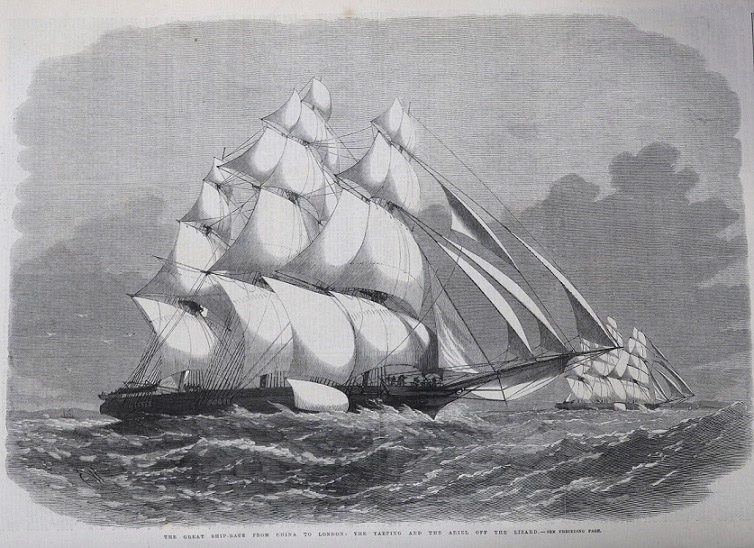

On 5 September Ariel and Taeping, which had last been in sight over 70 days ago, found themselves off the Lizard running neck and neck up the channel, with all their sails set to take full advantage of a strong westerly wind. They raced together for the whole day, darting up the channel until they reached Dungeness, when they signalled the pilot station for pilots to board and take towards the Thames, as required by law.

On the morning of 6 September both ships reached the Downs, where they needed to find steam tugs to tow them up the river. Both ships found tugs at about the same time, but Taeping found the more powerful one, and reached Gravesend some time before Ariel. Serica, meanwhile, followed in their wake, passing Deal at noon on the 6th, and reaching the Thames on the same tide as the leaders, a little over an hour later. Thanks to a faster and more powerful tug, Taeping docked in London Dock at 21:45, claiming first place, while Ariel docked at East India Dock only half an hour later at 22:15 and Serica docked at West India Dock at 23:30, within two hours of the victors.

Fiery Cross reached the Downs on 7 September but was compelled to drop anchor due to heavy winds. The clipper, which had for so long been in the lead, finally managed to get into London Dock by 08:00 on Saturday 8 September, with Taitsing arriving a few hours later.

Taeping was declared the winner of the premium, but due to the nature of the victory and the closeness in times, the prize was shared between Taeping and Ariel. The voyage for the first three ships took only 99 days, a whole week shorter than the time taken by Fiery Cross and Serica the previous year.

As things turned out, 1866 would be the last year in which a prize was offered for bringing back the first teas of the season. Despite the excitement and the acclaim, the premium proved to be unsustainable. Huge harvests in 1865 and 1866 had caused a glut in the market which meant that the cargoes of the first ships home were met with indifference and low prices from the buyers in London. The race continued for a few years, up to the 1870s, and even included the Cutty Sark as a competitor. By this time the era of the clipper ship had largely finished. Steamships were faster and were able to carry more cargo and were not dependent upon the prevailing winds.

In 1869 the Suez Canal was opened, providing a shorter route to and from China. This route was virtually impossible for sailing ships, which would have to be towed through the canal, and they gradually became obsolete as trading vessels.

Thanks for a great article. Really enjoyed reading so much detail about a near-forgotten part of maritime history.

Really fascinating, thank you!

I had always thought the Cutty Sark was the main competitor so this was an eye opener and so interesting. Thank you.

Such was the golden age of sail, its sounds romantic, but it must have been tough serving under those master mariners who never’spared the horses’. However, what a fantastic sight it must have been to see those ships racing up the channel under full sail, shame they are not on youtube!

Thank you for a fascinating and informative article. I enjoyed learning so much about the tea trade.

Excellent article – and a curious array of ships’ names. It would be interesting to know where they originated.

Were these races a purely British phenomenon, or did other countries stage them too?

Hi John,

You can find out quite as lot about the history of each ship online. Readers have also helpfully recommended David R. MacGregor, The Tea Clippers: Their History and Development 1833-1875, London: Conway and Lloyds of London Press, 2nd edition, 1984.

James

What an exciting story of Tea Clippers and details about their sailors? From pictures clippers are beautiful, finely designed sleek vessels looking magnificent in full sail. In our age of global warming maybe we might have sail ships again even if for short Channel or island to island ferry travel.

Our apartment is just ,a couple of hundred yards from the Cutty Sark so I thank you for such a detailed history. What a courageous and hard life it must have been.

Thanks for such an interesting article. It should be noted that the clippers continued in service after the tea trade as a cargo vessels right up to WWII where they were employed to carry first wool and then grain from Western Australia. Many of the vessels were under Scandinavian owners. Eric Newby’s wonderful book the Last Grain Race gives an idea of what it was like to crew the clippers around Cape Horn.

David R. MacGregor, The Tea Clippers: Their History and Development 1833-1875, London: Conway and Lloyds of London Press, 2nd edition, 1984 is another excellent source to supplement this valuable blog.

what a great piece of history . I really enjoyed reading it. A nice article for anyone researching their family tree.

It is a minor point in the context of your superb story, but the ship tonnages listed are probably not actual weights.

Merchant ship tonnage generally refers to the carrying (cargo) capacities of the vessel and is really a measure of volume. Modern day practice for Gross Register Tonnage is to equate 100 cubic feet of totally enclosed space to 1 ton. In the nineteenth century, tonnage was normally (or at least frequently) calculated from a formula involving length of the ship’s waterline, beam (width at the widest part of the ship) and the depth of the hold between the underside of the deck planking and the top of the keel (which was not necessarily the same as the depth in the water of the keel). Just to be even more confusing the specific details of the formula depended on the place at which the ship’s dimensions were calibrated!

So, the weights given in the Foochow Advertiser’s list are actually better measures of the length of the ships than of their weight. Both affect speed. The longer a sailing ship, the higher its theoretical maximum speed. The greater the weight of ship and cargo, the slower it will be to pick up speed as the wind strengthens but the less affected it will be by somewhat higher waves. It is not difficult to see why ship’s masters and owners wanted to compete against each other for bragging rights, let alone prizes or premium prices for their cargo!

The weights of cargo loaded on each ship probably excluded the weight of the metal lined wooden chests in which the tea was carried and so are real measures of the amount of tea carried. What’s thought provoking there is just how many cuppas can be had from one season’s cargo.

Some interesting new material here, but the writer needs to polish up on some nautical basics.

First “It was the lightest ship at 689 tons” – the tonnage of a ship is a notional measurement of volume, not weight. So this should say the “smallest” not the “lightest”.

“Every spare inch of space would be used up to carry as much as possible of the precious cargo. ” There are suggestions that Fiery Cross did not load the maximum amount of tea possible – this allowed a ship that already had a slightly shallower draft to get across the bar of the River Min when Ariel had to wait at anchor.

“…down the River Min and across the tidal breakwater ” It’s not a “breakwater”, it’s a “bar”. The former is manmade, the latter is a natural feature.

Stating that just Ariel was of composite construction is misleading. Of the first 5 ships Fiery Cross and Serica were built of wood – the other 3 were composite.

“To spice up the competition, an additional payment of 10 shillings per ton was allotted to the owner of the cargo of the first ship arriving in dock.” – This is completely the wrong way round. The owners of the cargo paid the extra 10 shilling per ton to the owners of the ship, with an additional cash sum going to the captain. This “premium” was written into the Bill of Lading of each of the competing ships.

“Thanks to a faster and more powerful tug, Taeping docked …..” No, the real difference was that Taeping was able to enter the dock that she was booked (London Docks) into because she was of less draft and, more importantly, those docks had an inner and outer set of lock gates. She could just get over the sill of the outer gate, which was then shut, then water from the dock was let into the lock so that she could get through the inner gate. Ariel, which had been waiting outside East India Dock gate for some time could not do this – she had a deeper draft and there was only a single gate that was opened when the tide was high enough -there was no lock to get into the dock at that time.

All this information is easily available with a few hours research of the basic books on the subject. I particularly recommend David R MacGregor’s The Tea Clippers. (Sadly out of print for some years, but still readily obtainable second-hand.)

So England switched over time from Chinese to Indian tea, I believe Britain encouraged the growth of Indian tea. I would be interested in an article explaining how that happened.

I enjoyed the tea race article.

love the story thankyou

Found this story very interesting. I did an article for a Probus Club on advertising signs for Griffiths bros tea. Some will remember the signs along the rail way tracks. 30 miles or similar saying 7 miles to Griffiths Bros tea. Also an interesting tea story from the Griffiths Bros Tea company.

David

This was a fascinating account but Im intrigued abt sailors being discharged in places like Shanghai & Hongkong. Why was this? Did the sailors just change ships or did they want a holiday? If the latter how did they exist in China wthout the language? Or did they just sign on to another ship? Would love some answers!

Hi Carol, Most of the sailors who left a ship in Chinese ports would have signed on to another ship. They carried with them what is known as a certificate of continuous discharge, which had details of the ships they had previously sailed on and the capacity in which they served and remarks on their character and conduct. The ports of Amoy, Foochow, Shanghai and Tientsin would have had a British consul and shipping master, and a British community based around the docks. Hong Kong was run as a Crown colony, and there would have been far less of a language barrier. After a long outward voyage which would have been physically very draining, some of the sailors may have wanted a change of captain. Some may have failed to return to the ship on time and would therefore have had to come back on another ship. With some the captain may have been happy to be shot of them and to find fresh crew. I hope that helps. James

An interesting article, but the Chinese government was brutally defeated in the First Opium War and forced to sign the 1842 treaty, with humiliating clauses, which has ramifications to this day. We were buying tea with drug profits.

What a wonderful history and the challenges these Cliipers have had. I love their stories. I Have travelled on the modern-day clippers run by the Royal clippers, a fantastic experience, makes you appreciate their heritage.

What an interesting article!

I regularly contribute articles to our local parish magazine. Would I be able to contribute this article or would I be infringing copyright?

Hi Greg,

You are welcome to use the text, so log as you quote that its origin is The National Archives. There are two helpful comments from readers which address inaccuracies regarding tonnage and other seafaring matters which might be worth adding at the end for balance. The images in the blog are very low resolution. You can obtain better quality images suitable for publication from our Image Library at https://images.nationalarchives.gov.uk/assetbank-nationalarchives/action/viewHome

James

I love the Cutty Sark and didn’t realise she came into the story of the tea clippers quite late on. I must have been a wonderful sight to see them in full sail racing up the Channel and along the Thames. Some years ago, I was researching a ship, Upton Castle, for my cousin, a ship’s master and pilot, and seeing the Cutty Sark enabled me to understand exactly how it was constructed. Thanks for an interesting article.

Hi, I live in Downham Market and Capt Woodget of the Cutty Sark lived here for many years . I have written a small article on him and his time in Norfolk where he was born , see http://www.downhammarkethistory.co.uk and pick Capt Woodget and the Cutty Sark.

The omission of the word ‘opium’ from this blog is genuinely staggering to me.

My father was a model maker, and he built a model of The Ariel. In the 1950s he had made a marquetry of The Ariel. Then he proceeded to make a model of The Ariel. As children we watched in amazement at his skill at working on such minute details. Although we had heard about tea clipper races from Dad, it was lovely to read about them ourselves.

I think the model was awarded a silver prize at the Model Engineers Society Exhibition in London, in 1961.

This is my ancestor’s recollection of his time on a tea trading clipper in 1848 that might be interesting to those who’ve also enjoyed this article.

I am hoping that someone reading this might know if there are crew records for cutters closer to 1848 or which companies might have been importing tea from Calcutta at this time.

“I made three trips to Calcutta as steward on a sailing vessel. That was in 1848, before the Suez Canal, and a voyage meant four months then. We carried tea principally. It brought 2/ a pound in England then. On the last trip we had a very severe storm near the Cape — eight days of it. Lost our boats, and the gale tore all the rigging about. We were hove to all the time. The seas seemed to come down from the tops of the masts on this little vessel of 300 tons. Old sailors said — ‘If we get out of this I’ll never come to sea again.’ A fortnight later I saw a lot of them looking for another ship. Don’t imagine I liked that gale. A sea banged me from one side of the cabin on the poop, through the dining-room door to the cabin on the other side. The captain was so worried about the prospects that he came on deck crying. I didn’t feel like living to 80 then, I can assure you. I was a lad of 20.” Interview with John Ford (1830-1914) in “The Register”, Adelaide, South Australia, 18 May 1910.

It would be interesting to know about other winners of the Great Tea Race. The race in 1869 I believe was won by the ‘Spindrift’, a vessel only 2 years old. Having unloaded their cargoes, three tea clippers left London for China in November 1869, presumably as part of the race, including the ‘Spindrift’. Although the ‘Spindrift’ had an experienced Trinity House pilot on board, Mark Martin, it seems the vessel tried to pass Dungeness rather too fine and it was wrecked on a sandbank. It started a vigorous discussion as to whether the Master or the pilot were in charge of the ship at the time.

Fascinating. Soon after in 1869 the Suez Canal was opened and the journey took 3 or 4 weeks on steam ships compared with 3 or 4 months on Tea Clippers.

Opium trade was mainly from India to China although tea was bought on barter trades. The Chinese became addicts and led to the Opium Wars after which opium trade ceased and workers anf plantation managers migrated to Eastern India – Assam/Dooars to start tea plantations there. British spies had in the mean time gathered information to start growing and making tea in NE India.