This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Great Smog of London, which occurred between 5-9 December 1952.

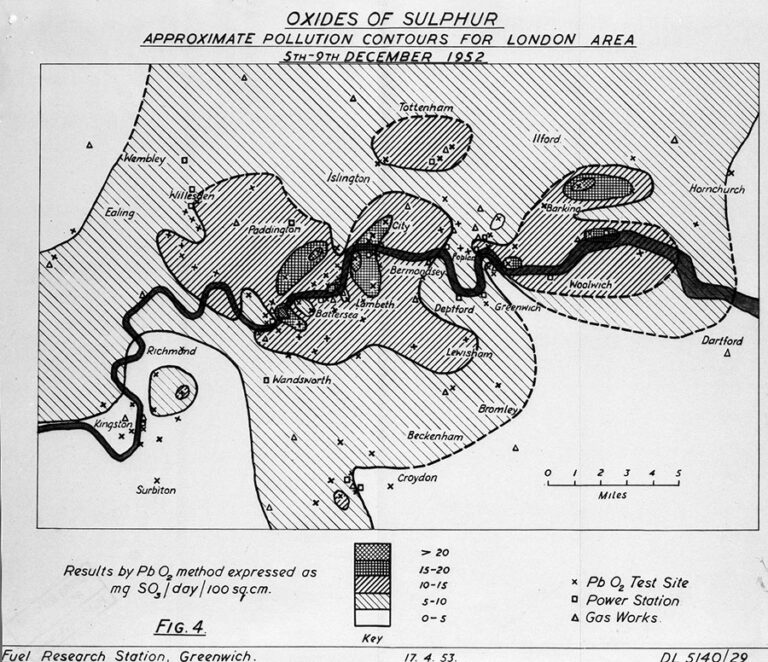

The event was of great significance in the history of public health, resulting in the passing of the Clean Air Act of 1956, which regulated the use of air pollutants. The type of fog, containing poisonous sulphur dioxide, was common in London at the time, arising from the widespread use of coal. The smog of December 1952, however, was particularly severe. The fog was so thick it stopped public events and the use of transportation. Its lethal effects were unprecedented: it is estimated that more than 4,000 people died in the immediate aftermath and a further 8,000 died over the course of the following year, mostly caused by respiratory tract infections.

The mortality estimates were taken at the time from the Registrar General’s Weekly Returns, with some additional data from the likes of coroner reports. The Chief Medical Statistician stated that ‘the incident was a catastrophe of the first magnitude in which, for a few days, death rates attained a level that has only been exceeded on rare occasions during the past hundred years as for example at the height of the cholera epidemic of 1854 and of the influenza epidemic of 1918-1919.’ (see footnote 1)

The incident also impacted animal health. A report shows that a number of cattle that had been brought along to the Smithfield Show at Earl’s Court from 8-12 December suffered from acute respiratory symptoms, with around 160 needing veterinary attention and 12 being slaughtered as a result (footnote 2).

One medical practitioner wrote to the Ministry of Health about his experiences of the smog, stating that he was convinced it had ‘wiped out a great number of people who would otherwise survived’ with their existing respiratory conditions. He went on:

‘I would have shared the fate of the Aberdeen Angus cattle at the Smithfield Show, for whom I had great sympathy and fellow feeling. I could not move for four days without the greatest distress … I must have been very bad indeed one night, for my wife actually held my hand and said she was sorry for me! That is proof enough that I looked as if I was going to kick the bucket. What are our wonderful scientists doing? In an age of jet propulsion, atomic energy, and all the miracles of modern science at which we marvel, these wretched people can’t solve the problem of a lousy fog!’

Letter from L F Beccle, Southern District Essex to the Ministry of Health, 13 December 1952, MH 55/2661.

Records held at The National Archives about the incident are broad. They include statistical and scientific data, meteorological reports, public testimony in the form of letters, coroner and medical reports, and memos and correspondence that reveal the extent of the state’s anxieties about air pollution in the period.

Government action

Air pollution was known to have an effect on health at the time, with conclusions being drawn from rising mortality rates and incidences of respiratory ailments following a period of fog (footnote 3). With the development of industry in Great Britain since the mid-18th century there was an extensive rise in the use of coal, which caused air pollution. London was infamous for its ‘pea soup fog’ and there had been attempts by the authorities to control pollution over the years via a number of acts, such as the Smoke Nuisance Abatement (Metropolis) Acts in the 1850s and the Public Health (London) Act in 1891. During the early 20th century there was an active Atmospheric Pollution Research Committee taking out research under the auspices of the Department of Scientific Research. It regularly measured pollutants in the air across major cities, which was collected by the Fuel Research Station.

Following the Smog of 1952 the government appointed Sir Hugh Beaver to chair a Committee on Air Pollution, which recommended that clean air should become an essential part of fuel policy in the future. The recommendations included ways to make industrial as well as domestic smoke cleaner, such as changing from house coal to smokeless fuels. As this would constitute a radical change in domestic heating habits, it would be in part subsidised by the public purse.

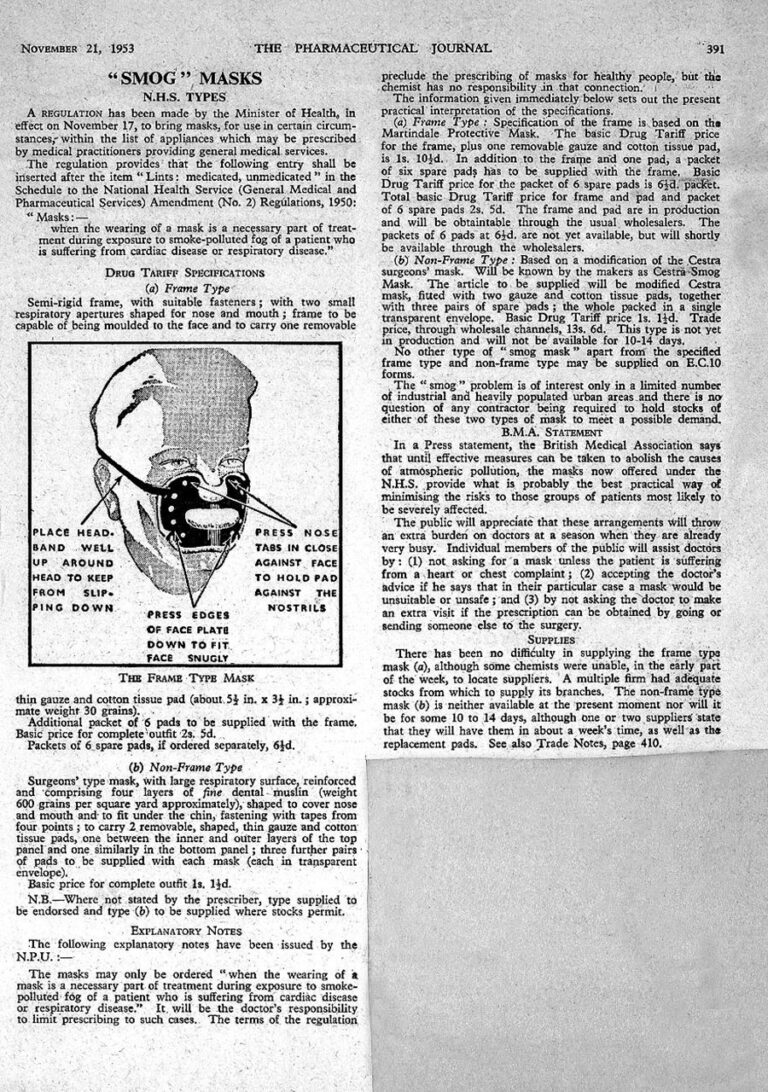

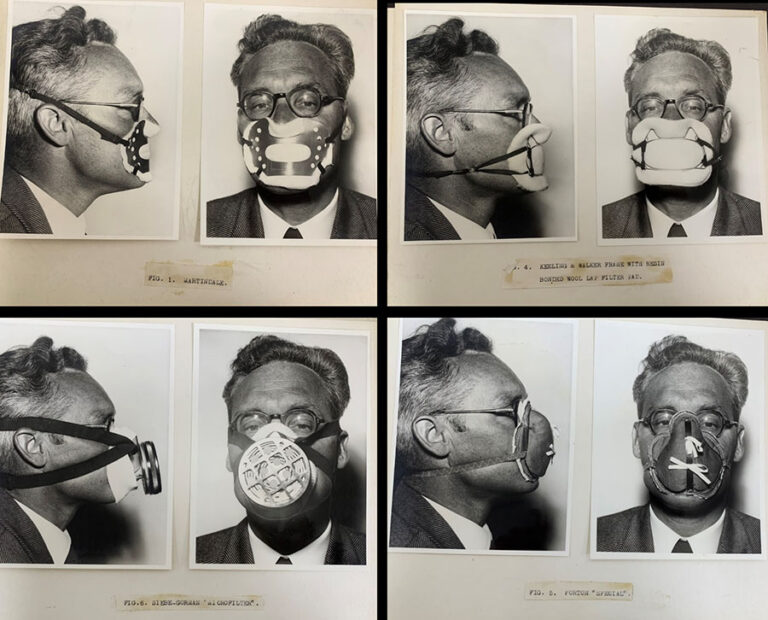

Records, including an article from the Pharmaceutical Journal from November 1953, one year after the smog, also reveal that the concern was so great that the Minister of Health enacted a new regulation that face masks could be prescribed by medical practitioners for patients suffering with pre-existing heart or respiratory problems.

Files show that research was undertaken on what kind of masks would be the most effective, with a focus on the Martindale mask. A number of questions were asked as part of a trial, such as ‘did you find the mask comfortable to the face?’, ‘does wearing the mask make breathing more difficult walking about?’, and ‘can you sleep in it?’ (footnote 4).

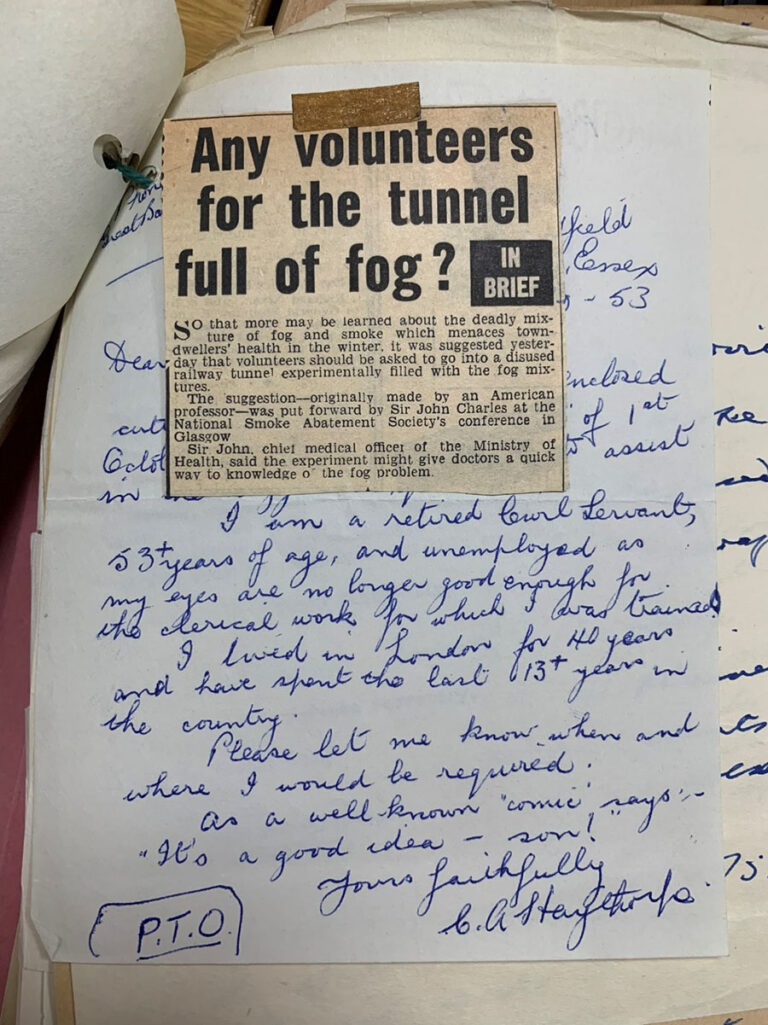

Other experiments were suggested. One member of the public was very enthused by the idea of an ‘experimental tunnel’ filled with pollutants that had been proposed by the Chief Medical Officer of the Ministry of Health, Sir John Charles, at a conference of the National Smoke Abatement Society in 1953. The 48-year-old wrote to the Ministry of Health declaring that ‘I hope that I may have the privilege of being included among the volunteers to undergo such treatment … if the fog has to kill us, it would be better to do it under controlled conditions so that there may be of some benefit to the rest of the world.’

The Ministry, however, responded that the planning of a ‘smoke tunnel experiment’ had been misreported and there were no plans to carry out the suggestion.

Lived experiences of the Great Smog

Records also include coroners’ and medical reports about the effects of the fog. It was noted that one 33-year-old housewife, who had a history of chest trouble, in the borough of St Pancras, ‘was at home during the foggy period, being removed to hospital on Tuesday 9th December only a few hours before she died. She complained of the fog which penetrated into her room. The fog would appear to have accelerated death, as the sudden deterioration in [her] condition was apparently unexpected by the doctor in attendance.’ (footnote 6)

While smog was widely recognised to really only impact those with pre-existing chronic respiratory or heart conditions, this was not always the case. One 61-year-old lady who ‘had never had any chest trouble prior to the onset of the fog on 4th December’… ‘became ill on 6th December’. By the 9th ‘her breathing became distressed and in the evening she became unconscious’ passing away the next day (footnote 7).

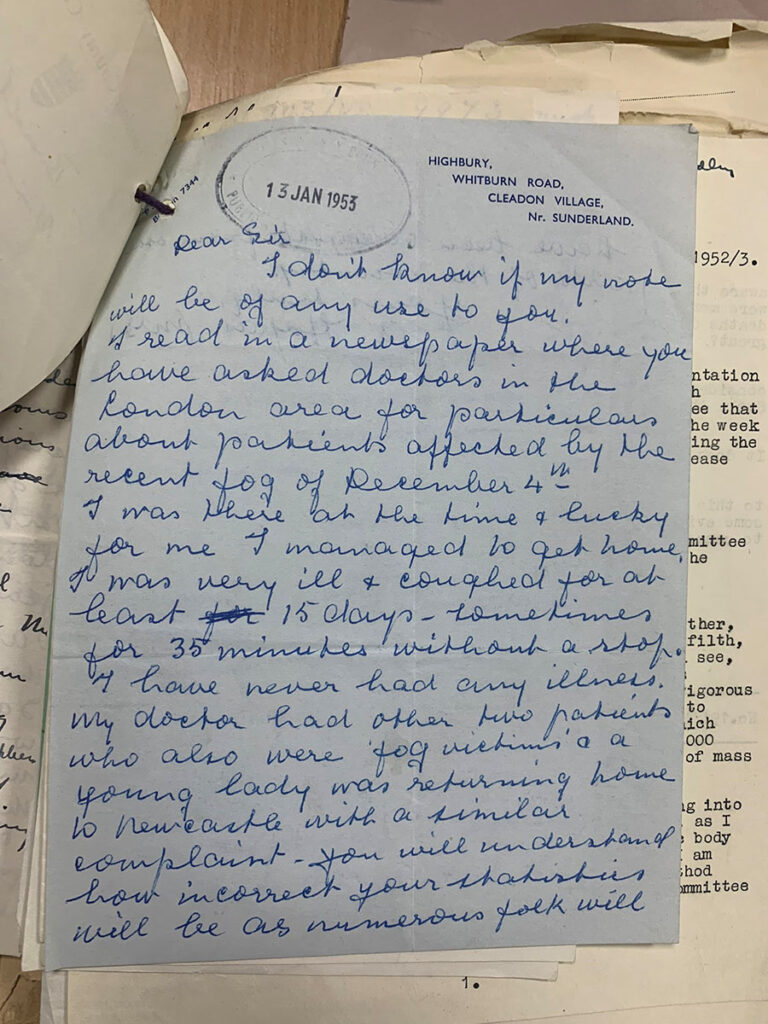

Records highlight some of the lived experiences of people caught up in the smog. One member of the public wrote to the Ministry stating that, despite never having any illness, ‘I was very ill & coughed for at least 15 days – sometimes for 35 minutes without a stop’. They noted that statistics would likely be inaccurate as they would not likely cover people who were visiting London and had gone home to other parts of the country feeling the effects of the smog.

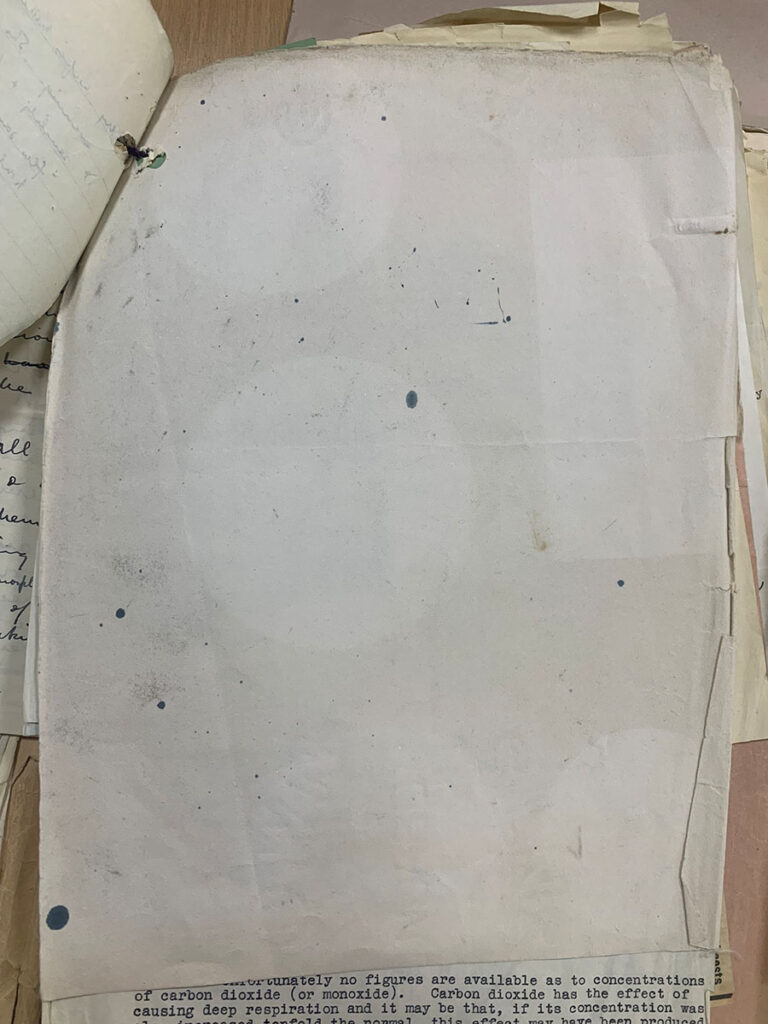

Incredibly, a piece of blotting paper showing the effects of the smog also appears in the files. It was sent into the Ministry of Health in January 1953 by a member of the public (footnote 8). The relatively whiter circular sections on the paper are where ink-pots were sat, clearly showing the effects of the pollution some 70 years later.

All these records relating to the Great Smog of 1952, including files from a range of public health departments, policy makers, coroners and government chemists, help us today to understand the social, economic and medical effects of air pollution.

Footnotes

- W P D Logan MD, Chief Medical Statistician, General Register Office, The London Fog Incident, 1952: Mortality Aspects, MH 55/2661.

- G R Hudson, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Veterinary Laboratories, Weybridge, The Effect of the Fog on Cattle at the Smithfield Show, MH 55/2661.

- ‘Effect of Fog on Health’, Large cities: effects on mortality and respiratory diseases, MH 55/2658 (1931-1938).

- Mask questionnaires, c.1953-1954, MH 58/859.

- Letter from A W Hunt to Sir John Charles, Ministry of Health, 1 October 1953, MH 58/859.

- Public Health Report Upon Death Attributable or Accelerated by Fog, 33-year-old housewife date of death 09.12.1952, Metropolitan Borough of Saint Pancras, January 1953, MH 55/2661.

- Report of 61-year-old lady, date of death 10.12.1952 from acute bronchitis, 1953, MH 55/2661.

- Blotting paper enclosed with a letter from I C Lamont to the Ministry of Health, 9 January 1953, MH 58/398.

Slightly unexpected that it looks like Richmond Park appears as an island of relatively high air pollution on the map. Possibly because slightly lower temperatures that are often found in the park helped fog to form?

I remember it vividly. We lived in Wallington in a valley which trapped the smog well. Gran had been a nurse and was living with us at the time. She insisted we all stay indoors with the curtains closed. So we did, listening to the radio and reading. For some reason I went into the hall and there saw the smog pouring like water through the open letter box. I shut it and coughed. There was a small sea of smog in the hall.

For the next couple of days we stayed at home until Gran announced we could leave the house. A few months later we took the curtains down and washed them in the bath: the water was a thick brown colour and it took three washes to get rid of it.

I was four at the time of the Great Smog and living in a ground floor flat in Goldhawk Road, Shepherds Bush. I can remember not being able to see clearly the opposite wall of our small sitting room because the smog had somehow got through the window.

I remember walking with my father when we left Guilford by the green bus and we went to Wandsworth near the gas station and were dropped off there and we walk to my grandmothers house.

Our walk was about a quarter of a mile maybe a little bit more, but my father always told me to keep my scarf securely wrapped around my face around the mouth area, and I remember you could hardly see more than about 5 feet in front of me the fog it was so thick it was a good job that my father knew the way to my grandmother’s house because I would’ve never found my way on my own as I was only 3+ at the time.

I remember walking home from Liverpool street station, London to Hackney E.9. The company I worked for at Holborn Viaduct let us go home early because of the smog where a 22 bus picked us up and was lead by someone walking in front with a wooden flare, By the time we made it to Liverpool station, all public transport had stopped. Not sure what time I arrived home but was very glad to get there alive as I had to guess if I had reach the curbs when crossing the roads, couldn’t see a thing or hear any traffic. Because I suffered with chest problem it was a week before I could return to work,

The year was 1963 as far as I can remember.

I remember the 1953 smog. I was seven years of age. We lived at the time in Putney, and spent weekends in Brighton to get away from the air pollution. My father had heart problems from which 5 years later he died.

We drove down to Brighton on a Friday evening in thick smog, I remember the smog was so thick that neither the driver nor passengers could see the road kerb and my mother had to walk beside the front of the car to identify the whereabouts sof the road that ran along the edge of Wimbledon Common.

Why is this called the Great Smog of London? It was very bad in Manchester as well when I was 5 and probably other big cities too. Ann Bennett

I well remember arriving at Victoria Coach Station to catch the coach back to Boscombe Down where I was doing my Nat. Service, it was a Sunday night and we were ultimately issued with a blanket and tried to sleep until daylight. We arrived back in Wiltshire by lunchtime on Monday

I clearly remember the 1952 pea souper fog, I was 12yrs old at the time and found it to be quite interesting untill I ventured out of the house in West Norwood. I walked a short distance from our house and then became a bit worried due to visibility dropped to almost nil, I could not see my hand in front of my face, the fog seemed to become more cloying with every breath I took and it was starting to cause me difficulty breathing, luckily I got home as I had not strayed more than 25yrds, even so I got home by luck more than anything else. At the time of the fog we lived near West Norwood railway station.

I have lived in Australia since 1955.

In coal mining districts the air also became filled with particles thrown out when coke ovens were emptied. Even on a bright day these could be seen to land a mile away, on washing hanging on the line, so had to be rinsed again. Referred to as “smuts”.

The smogs were common in all urban areas in England during early 1960s in the winter months depending on which way the wind blew.There was always a string smell of coal !

When we moved in 1952 for my father’s job (when I was three ) over the Pennines from Greenfield, Saddleworth to Wath -on -Dearne, also in the West Riding of Yorkshire, and since 1974 in South Yorkshire, my mother was shocked at seeing soot floating from the sky onto the washing on the line.

This was due to domestic coal fires and the neighbouring miners having a generous free coal allowance which, I think, encouraged these. Hot water was obtained by means of a back boiler and I remember seeing a blazing open fire on a hot summer’s day at a friend’s house whose father worked at Manvers Main Colliery and Coking Plant.

I thought sheep were grey until we travelled away on holiday and I saw white ones!

I was 11 in 1952 and had started school in Hammersmith in September. I travelled home from Hammersmith to Fulham on the 655 Trolleybus and then had to walk from Fulham Palace Road to Munster Road, which normally took a few minutes. I had a torch which was of little help! I started my walk by aiming at the glow of the next street lamp; the lamp itself being invisible from more than a couple of yards away. I soon realised that I was walking in the road and had no idea which direction I was aiming myself. Eventually I completed my walk home with one foot on the kerb and the other in the road. I wasn’t very tall but even I could not see my feet all the time. I held a handkerchief over my nose and mouth as my mother had instructed, but even then I carried on coughing for a long time after getting home.

My family lived in Mexborough in the middle of the South Yorkshire coal fields. In 1949, aged 9, we moved to Norfolk for cleaner air as my father had chronic asthma. One November half term we visited my paternal grandmother in Mexborough. She opened the back door and exclaimed ‘What a lovely day’. The sky was blue and the sun shining – but I thought it was foggy because of all the smuts in the air.

My parents talked of the 1952 smog. They lived in a basement flat in Earl’s Court. I was a 7 week old baby and apparently when my mother picked me up from my bassinet I had black around my nose. My auntie was visiting from Ireland and was very upset thinking it was the end of the world as in the middle of the day it went dark.

It was the beginning of my parents planing to leave London and England for the sake of our health. They moved to the fresh air of New Zealand as soon as they could.

I was eight years old in 1952 and living in Mitcham, South London, my mother suffered from Bronchiectasis and pulmonary fibrosis. We didn’t have access to proper face masks so she made do with several layers of chiffon scarf tied round her lower face and stayed in bed to conserve what little energy she had. I remember the smog sort of swirled if there was any movement. Inside the house did not escape, it penetrated the sideboard which meant all the crockery and glass stored there needed a wash to remove the black layer of soot.

I was 16years of age and going home from work in London to a new house that our family had moved into in West Sutton. When I walked up the Station steps I suddenly realized that neither of my parents had given me the house number that they had moved into that day. What a dilemma! I stood at the station entrance with that smog surrounding me wondering which way to go. I could barely see anything in front of me. I turned left as I left the station, crossed the road and kept walking wondering which house that they were in. Suddenly I noticed a house that did not have proper curtains at the windows through a sudden lifting of some of the smog. I wondered if that was the one. I approached the door and luckily for me it was the right house.

I was 8 years old and lived in Thornhill Road, Islington. I can remember walking to Thornhill Road School which was only a matter of a quarter of a mile and not being able to see in front of me. My father worked in Holborn and I can vaguely recall him arriving home very late due to the smog

My 18th Birthday was in October 1952. I was a member of the Finchley Harriers Athletic Club and we had a regular Wednesday winter training session at the Met Line sports ground. The youth group, was about 12 of us, and we would all run together through the dimly lit streets of Neasden and Kingsbury. This was the first time I noticed how really bad was the visibility. I took the bus home and it seemed ok there as our house was on a hill midway between Neasden and Cricklewood. On Friday evening I went to the Cinema in Neasden and when I tried to pay they said it was “free” However, the visibility inside meant that you had to sit in the first three rows which was a waste of time. I went to Ruislip to run in a cross-country race on the Saturday and the weather and visibility was excellent. That evening I took the Number 16 bus from home with the intent of going to meet my friends in Kilburn, and as we went down hill into Cricklewood the Driver called the conductor and said we are turning around and he would have to walk in front with a torch. Now, what should I do? Well I’m right outside the Galtymore Irish Dance Hall. That changed my whole life but that is a different story.

I have been giving an annual lecture about the Great London Smog at universities since 1990. I’ve also given it many times to the public. It never fails to shock and surprise audiences.

Most interesting. I believe I now know what has been wrong with me all my life. Thank you.

this is so sigma and real. on god feel bad but all those peps

got smoked fr tho