Between the abolition of slavery in 1834 and the First World War, more than 500,000 labourers were introduced to the British West Indies under terms of indenture. There has been much debate among historians about how and why indenture occurred. This blog will explore the impact of free trade and tariff reform on the emergence of regular indentured emigration to the West Indies by the 1850s.

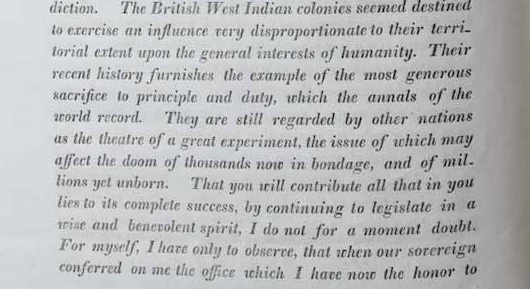

In October 1842, Lord Elgin, Governor of Jamaica, addressed the Jamaica legislature remarking that the West Indian colonies were ‘the theatre of a great experiment, the issue of which may affect the doom of thousands now in bondage, and of millions yet unborn’. For many of Elgin’s generation, including men like Lord John Russell, Lord Stanley and 3rd Earl Grey, concurrent Colonial Secretaries of Britain in this period, abolition of slavery in the sugar colonies was a test of monumental significance. Could free labour produce sugar more cheaply than that produced by slave producing colonies?

A headache for planters

In the free West Indies, the supply as well as the quality of labour was determined by two factors: population density and availability of arable land. Where the ratio of people to arable land was high – as in Barbados, St Kitts, and Antigua – estate labour was comparatively plentiful. Where the ratio of people was low – as in Jamaica, Trinidad and British Guiana – estate labour was scarce.

Moreover, in low density colonies enslaved workers had developed an attachment to independent land holding. Their desire to practice peasant agriculture after emancipation was consolidated by the seasonal nature of free labour sugar production.

After 1838 and the end of apprenticeship, planters could not guarantee all freedmen annual labour. In simple terms, the seasonal character of sugar production, combined with the new circumstance that free peasants now pursued independent farming, meant that planters could no longer command a pool of reliable estate labourers during peak periods.

In colonies like Trinidad and British Guiana, freedmen worked only three or four days a week on plantations. They worked for wages to purchase land, household items or luxuries and retired from estate work until a new demand for income arose. Employers were unable to determine what number of people would appear for work on a given day, which compromised planning of estate routine.

The real problem for planters was that labourers could happily subsist independent of labour for wages. This truth was observed in a colonial dispatch from Governor Metcalfe of Jamaica to Lord Russell in November 1839:

‘He [the labourer] may have recourse to labour for wages for the sake of money, or handsome clothing, or luxuries; but he is hardly ever reduced to it from absolute necessity. The usual order of things prevailing in other countries is thereby reversed in this; and it is here no favour to give employment, but an assumed and almost acknowledged favour to give labour.’

Metcalfe to Russell in CO 137/240. no.22, 14 November 1839

Developments in the British West Indian sugar industry in the first decade of freedom did not inspire confidence in British investors. Data collected by governors, stipendiary magistrates and investigating committees in England and the colonies left little doubt that in colonies with low population density, free-labour sugar production entailed higher production costs, lower output and reduced profits.

Henry Barkly, MP, future governor of British Guiana and Jamaica, testified in front of the Select Committee on Sugar and Coffee Planting, stating that his Guianan plantation had produced 616 hogsheads of sugar in 1834. In the first nine years of freedom, the average yield fell to 250 hogsheads a year. Simultaneously, costs of production had more than quadrupled by the time he appeared before the Select Committee in 1847. The table below illustrates lower yields and rising costs (labour, maintenance of property).

Table: Costs of Sugar Production, Highbury Estate, British Guiana 1831-1847

| Years | Hogsheads (Quantity) | CWT (average weight) | Cost of production (per CWT) shilling/d |

| 1831/1832/1833 | 457 | 7,000 | 6s 8d |

| 1835/1836/1837 | 505 | 8,122 | 6s 1d |

| 1839/1840/1841 | 238 | 3,454 | 40s 3d |

| 1842/1843/1844 | 250 | 3,750 | 30s 7d |

| 1845/1846/1847 | 269 | 4,055 | 25s 10d |

In Trinidad, Governor Harris reported in 1847 that only 17 of 193 estates were returning a profit and speculative capital investment had now ceased. Harris claimed that no sugar was produced in the colony for less than 12 shillings .6d. per tonne, and that the average cost of production was between 16 and 20 shillings (Harris to Grey, 21/02/1848, CO 295/160, no. 71). In Jamaica, 140 sugar estates had been abandoned since the abolition of slavery due to high costs of production and inefficiency. In these colonies, planters chastised freedmen for failing to perform careful continuous labour, but the planter did not and could not offer the workers continuous employment. The short supply, irregularity and high cost of labour curtailed or eliminated plantation profits and discouraged capital investment from London.

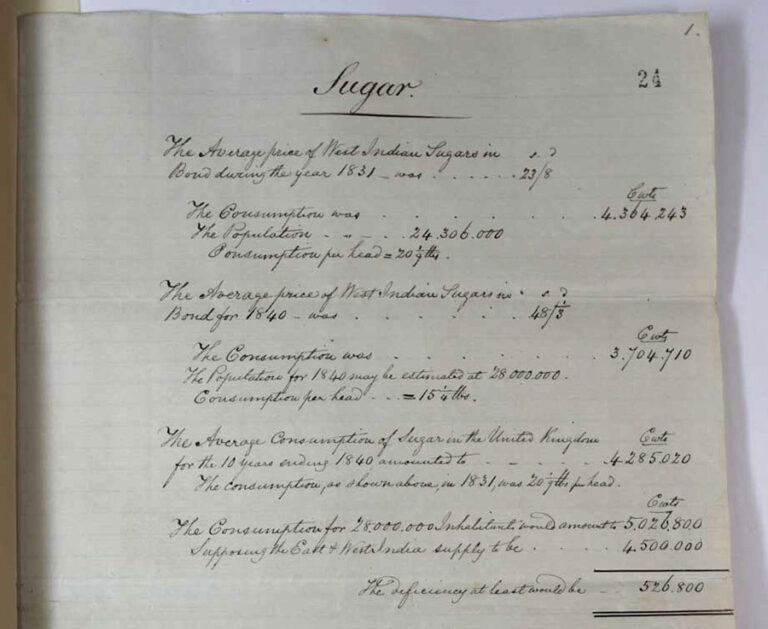

At the Colonial Office Lord Russell, Colonial Secretary, was all too aware of the situation. In PRO 30/22/4A Russell noted that the per capita consumption of sugar in the United Kingdom had fallen from 20lb in 1830 to 15lb in 1840. In the same year, the price of sugar in Britain reached its highest level since 1818. The protective duties which obliged British consumers to buy high cost, colonial sugar rather than cheap, enslaved-grown sugar constituted a weighty tax on the mother country.

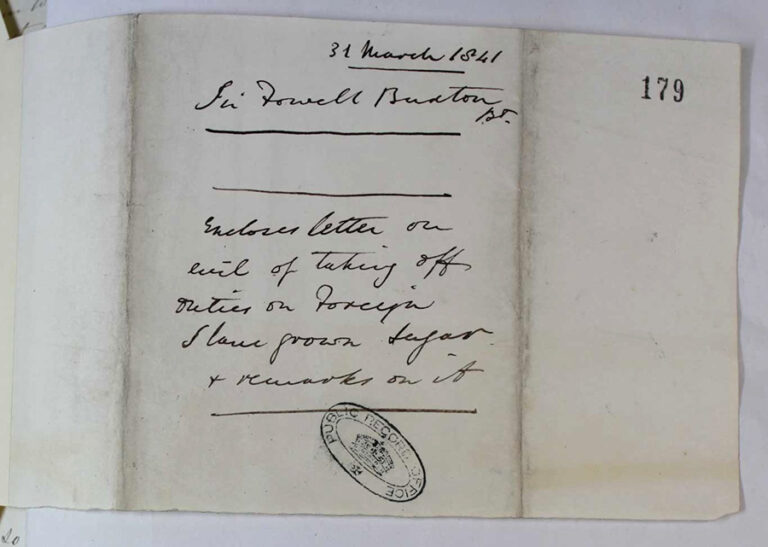

Also in PRO 30/22/4A the abolitionist campaigner, Thomas Buxton, appealed to the government not to allow enslaved-grown sugar to be purchased on the British market. Buxton stated that if foreign sugar could only be obtained through ‘the medium of the slave trade – the public would not call upon the government to instigate such a crime’.

Russell however, had to contemplate other factors, foremost of which was the consumption required by the British working classes during the period of what later would be referred to as the ‘Hungry forties’. A dietary necessity was fast becoming a luxury for working people. Because colonial production had declined, all British West Indian sugar was now being consumed in Britain, and the full weight of the colonial monopoly was being borne by metropolitan consumers.

Should, then, sugar duties protecting planters be abolished and what effect might this act have on the British West Indian economy and society?

Protection versus free trade

Leading British politicians now believed in the doctrine of laissez faire – free trade. Peel’s Conservative government repealed the Corn Laws permitting cheap food imports in the summer of 1846. Soon after, Lord Russell as the new premier carried the Sugar Duties Act allowing importation of cheap enslaved-grown sugar into Britain. Russell attempted to steer a moderate course between the domestic needs of British workers, the demands of plantations, and the nation’s legitimate concerns for freedmen in the Caribbean.

To help solve the problem of labour shortage in the British West Indies, Russell permitted immigration of free labour, initially from other West Indian colonies like Barbados, and then when this proved fruitless, from Africa. Sierra Leone, a haven for free Africans, and the Kroo coast of Africa were, from 1841, a new source of labour.

Free Trade ideology dictated that if Africans could be introduced to the West Indies in large numbers, they would increase the ratio between population and land, stiffen competition for wages, improve the quality of work performed by wage earners, and importantly, permit the planters to market their sugar at lower cost.

As early as 1840 the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission was established to supervise the migration of British subjects. The Treasury, moreover, in CO 318/151 supported limited emigration from Sierra Leone, declaring it beneficial to Africans, West Indians and British taxpayers alike. However, after an initial burst, emigration from Sierra Leone declined rapidly.

It was only when African emigration proved unsuccessful that a new Colonial Secretary, Lord Stanley, in co-operation with the Indian government revived Asiatic emigration in 1844. Agents were established at Calcutta and Madras together with regulations governing vessels and distribution of immigrants at their destination.

In CO 295/144 immigrants were assured of free medical care, minimum wage rates, food and clothing. Planter jubilation at the resumption of Indian immigration was tempered however, by its high financial cost. Large public loans were necessary, but commissioners representing the colonies had difficulty raising the money in Britain (CO 318/167).

That the situation in the West Indies sugar economy was already dire is illustrated by the table below concerning British Guiana.

Table: Abandonment of Plantations, British Guiana, 1838-1853

| Year | No. under cultivation | Abandoned |

| 1838 | 308 | – |

| 1846 | 251 | 57 |

| 1847 (Jan 1) | 235 | 16 |

| 1848 (June 30) | 210 | 25 |

| 1849 (Dec 31) | 196 | 14 |

| 1852 (June 30) | 183 | 13 |

| 1853 | 173 | 10 |

| Total abandoned | 135 |

Between 1838 and 1853 there were 201 execution sales, in which 175 estates – nearly 60% of the plantations under cultivation in 1838 – changed owners due to bankruptcy. Almost pandemic proportions. Estates accumulating huge debts due to increased production costs and free waged labour costs.

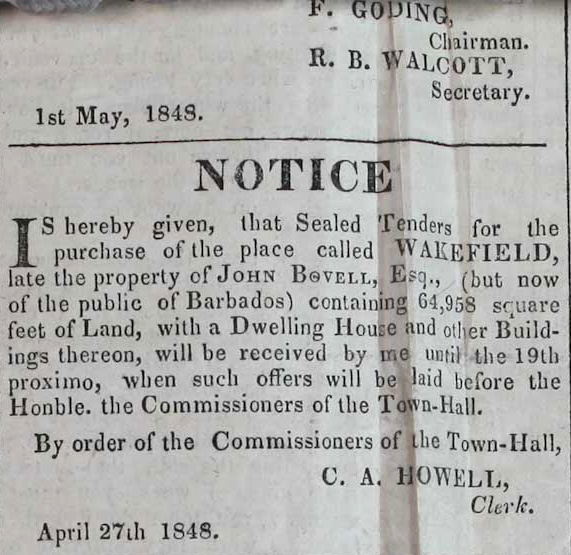

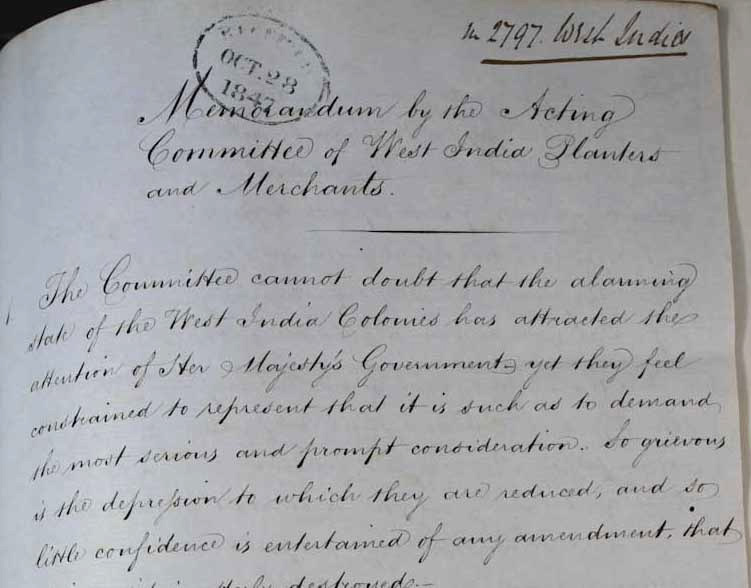

The Sugar Duties Act evoked protests and a unanimous cry of ruin from the West Indian planters. Former masters of enslaved workers incongruously denounced Russell for sacrificing morality to mammon. In CO 318/170 the Acting Committee of West Indian Planters and Merchants now cited the principles of free trade, demanding unrestricted access to the coast of Africa and elsewhere to procure immigrants. Numerous petitions were submitted to the Colonial Office demanding compensation for the colonists, managing to convince both Russell and Grey to reduce the differential duties on sugar for the next six years.

The immigration of indentured Indian labour played a decisive role in the recovery of West Indian sugar colonies, particularly Trinidad and Guiana. Russell’s offer of an immigration loan, financed by Treasury, was eventually accepted by planters.

However, it was expensive. The immigration of 21,784 Asian workers to the sugar colonies between 1845-1848 – with rations, medicine and accommodations – amounted to a daily charge in Jamaica alone at 2 shillings 3d a day. (See Report in CO 137/296, no. 26, 6/03/1848). In Trinidad, Governor Harris determined that during the initial year of acclimatization planters were sustaining a dead loss of £10 per immigrant after deducting the value of their labour.

‘It may further be asked whether many of the estates now in cultivation could ever recover from such an enormous charge on them that this system of immigration must entail.’

Harris to Grey, Colonial Secretary, in CO 295/152 no. 121, dated 28 December 1846

Trinidad invested £155,042 in immigration between 1838 and 1848, £83,048 spent in 1846-47 alone (Harris to Grey, CO 295/157, no. 68). Harris complained to the Colonial Office about indenture contracts being limited to one year, and immigrant workers who repaid their passage through bonded labour were under no obligation to re-contract with their original employer. Only later, in 1854, were new ordinances passed controlling work, wages and freedom of movement of labourers.

Conclusion

From the beginning, indentured labour migration was related to tariffs. When colonial sugar production fell, prices rose and consumer demand, as well as consumer irritation in Britain, grew. Unless the colonies acquired sufficient labour to extend production and reduce prices, they were likely to confront selective tariff cuts placing them in unequal competition with slave labour sugar producers.

In 1846 there was little chance that Caribbean proprietors, despite their appeals to humanitarian conscience, would be spared the same treatment. In 1840 indentured labour migration was viewed as a means of relieving public pressures for selective reform of the sugar duties; by 1850 it was seen as the only means of redressing the damage occasioned by general tariff reform. From the 1850s indentured immigration guaranteed West Indian planter profits, a productive export economy and economic and social stability in the free British West Indian colonies.

Thank you for this great piece of research. Important work.

This is really interesting thank you

Fascinating article with lots of detailed research.

A fascinating read, well researched

I found this a most interesting and thorough piece of research. Thank you.

Fascinating. Thanks

A very informative and highly interesting piece of work, thank you.

very interesting post thank you, fascinating to see extracts of the original documents

A revival of slavery in disguise! So very interesting and enlightening …

many thanks !

What a brilliant piece. The National Archives are so extraordinary and it is wonderful to see the picture of the original documents beside this excellent historical picture.

How little we know about daily-used goods like sugar that are taken for granted. Hearing the backstory about the migrant workers makes for uncomfortable yet informative reading.

Interesting stuff – will be v useful for my work on 18 and 19th century Britain

Fascinating research. It has left me wanting to know more about the impact of indentured Asian labour on sugar production in the West Indies.

Fascinating insight into this topic. Clearly explained and supported by the evidence. Thank you.

As I learned, slavery was not ended by the sudden moral imperatives, but by simple economics. Sugar had failed.