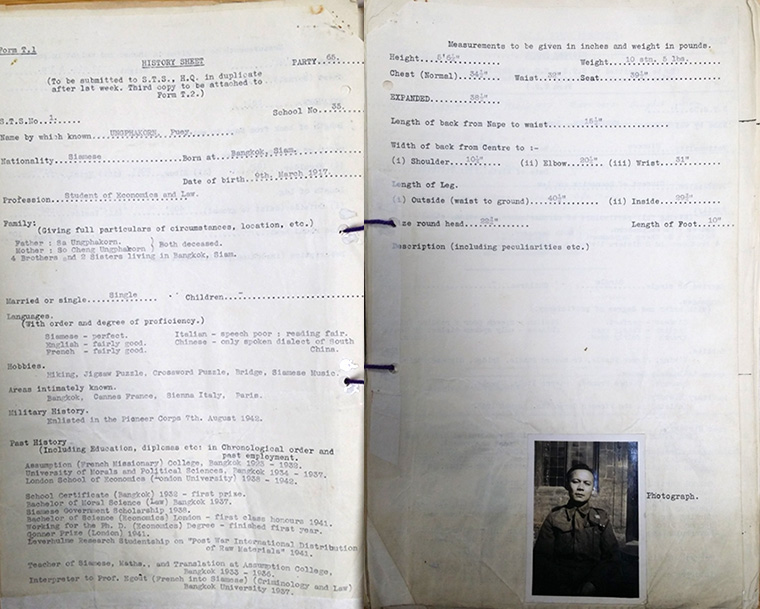

To commemorate the end of war in the Far East, which officially ended the Second World War, I will be referring to Dr Puey Ungphakorn, a Thai academic who studied prior to the war as a Leverhulme Research Post-Doctoral Studentship at the London School of Economics (LSE). He later became a leader of the Free Thai Movement in the UK, and also held a position in the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the war.

His principal role in both organisations was to establish contact between the Allies and leaders of the Thai resistance movement in Thailand. The work of both Ungphakorn and the Free Thai Movement was instrumental in setting up communication lines to convey intelligence behind enemy lines. Such information dissemination was one of the factors that brought an end to the war.

Thais in the UK at the outbreak of war

Siam (present day Thailand) was one of the first countries in South East Asia to have been invaded by Japanese armed forces. The invasion took place on 8 December 1941. However, despite fierce resistance from both indigenous Thai civilians and army units which were garrisoned locally, the Thai military government (under Field Marshal Pibulsongkram) signed an armistice with Japan. This treatise granted Japan permission to use Thailand as a military operational base from which to launch invasions against Burma and Malaya.

The alliance between Thailand and Japan was formally signed on 21 December 1941, and as a result Thailand joined the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Subsequently Field Marshal Pibulsongkram declared war on both Great Britain and the United States on 25 January 1942.

Fortunately the United States government did not declare war against Thailand, and indeed the Thai Minister in Washington, Seni Pramoj, denounced Bangkok’s military regime and its alliance with Japan. The United States seemingly understood that the joint Thai-Japanese declaration was made against the will of the Thai people, who strongly disapproved of the declaration of war. The Thai people also disagreed with their country being used by Japan as a base for operations for an invasion of neighbouring countries.

Great Britain’s wartime attitude differed greatly from that of the United States. After Thailand signed the military alliance with Japan, Thai students in England, disagreeing with their government back home, approached the Thai Minister in the UK about setting up an underground movement.

Phra Manuvedya Vimolnard, the Minister in London, handed the British government Thailand’s declaration of war against Great Britain. At the same time he discouraged any attempt by Thai students to form a resistance movement. Britain subsequently declared war on Thailand, and as a result Thai government funds were frozen (HS 1/65). Thai students and the Thai community in the UK were declared enemy aliens, and consequently they were subject to stricter regulations.

The Thai Minister in Washington became concerned over the plight of Thai students in the UK after communicating with two of them based at Cambridge University and the LSE. He was worried that the students’ situation was becoming increasingly precarious, because if they refused repatriation to Thailand they would face destitution, as they were ineligible to work in the UK or permitted to enlist in the British armed forces. Conversely, if they accepted repatriation, those who had openly declared themselves in favour of the Free Thai Movement risked facing the severest penalties at the hands of the Japanese.

Faced with such circumstances, at the beginning of March 1942 Seni Pramoj sent one of his representatives to London to explore the possibility of funding a Free Siamese Movement in London (HS 1/65). Mani Sanasen, who was well-connected both in London and Geneva, met Sir Gerald Campbell, British Consul General in Washington, and explained he wanted to set up an organisation in London that

‘would not only be to organise every assistance to the United Nations during the present phase of military operations, but also to prepare a Siamese cadre of trained men who would be able to give valuable assistance when the allied counter offensive actually takes place in the region of Siam’. (HS 1/65)

Campbell responded positively to the idea, and Seni Pramoj subsequently asked Mani Sanasen to go to London to explore the possibility of starting the movement.

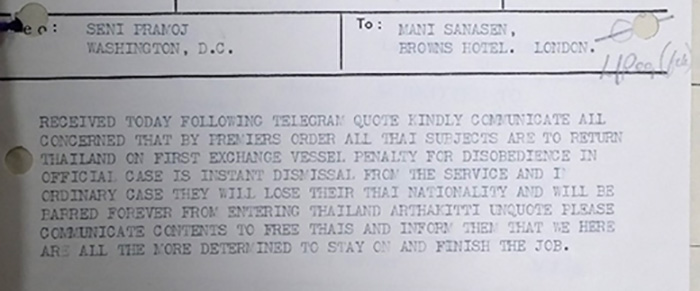

Repatriation of Thais

In June 1942, about the same time as Mani Sanasen arrived in London, negotiations were taking place for the exchange of prisoners of war and the internees between England and Japan. On 9 June, the Thai military government announced that all Thai subjects were to return to Thailand on the first exchange vessel. It stated that the penalty for disobedience for legation officials was instant dismissal from the service. The penalty for non-compliant students was far more severe. They would lose their Thai nationality and would be barred forever from entering Thailand.

This government announcement caused derision among the majority of Thai students, although a few students and legation staff decided to comply and return to Thailand. On 18 July 1942 the exchange party returning to Thailand consisted of Minister, Phra Manuvedya Vimolnard, and two other legation officials together with 23 other people, most of whom were students. Five students from Ireland also left London for Thailand. However, despite the threats of such a severe penalty, about 50 Thais decided not to return, and with the help of Mani Sanasen formed the Free Thai Movement in the UK.

About 36 of the Thais, most of them student members of the Free Thai Movement including Puey Ungphakorn, volunteered for service with the British Army and enlisted in No. 253 Pioneer Company. They were subsequently posted to India for further training in parachuting, map reading and paramilitary courses.

By early 1943 the SOE had become intimately integrated into the South East Asia Command (SEAC) and other covert operation organisations, including Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), the escape organization (MI9) and Office of Strategic Service (OSS). Such organisations promoted clandestine operations in the Far East and needed to recruit agents who could pass for natives. Operatives had to be sympathetic to the Allied cause and possess both linguistic skills and geographical knowledge of the country. On 30 April 1943 Puey, together with 23 other Thai students, passed the training and joined Special Operations Executive Force 136.

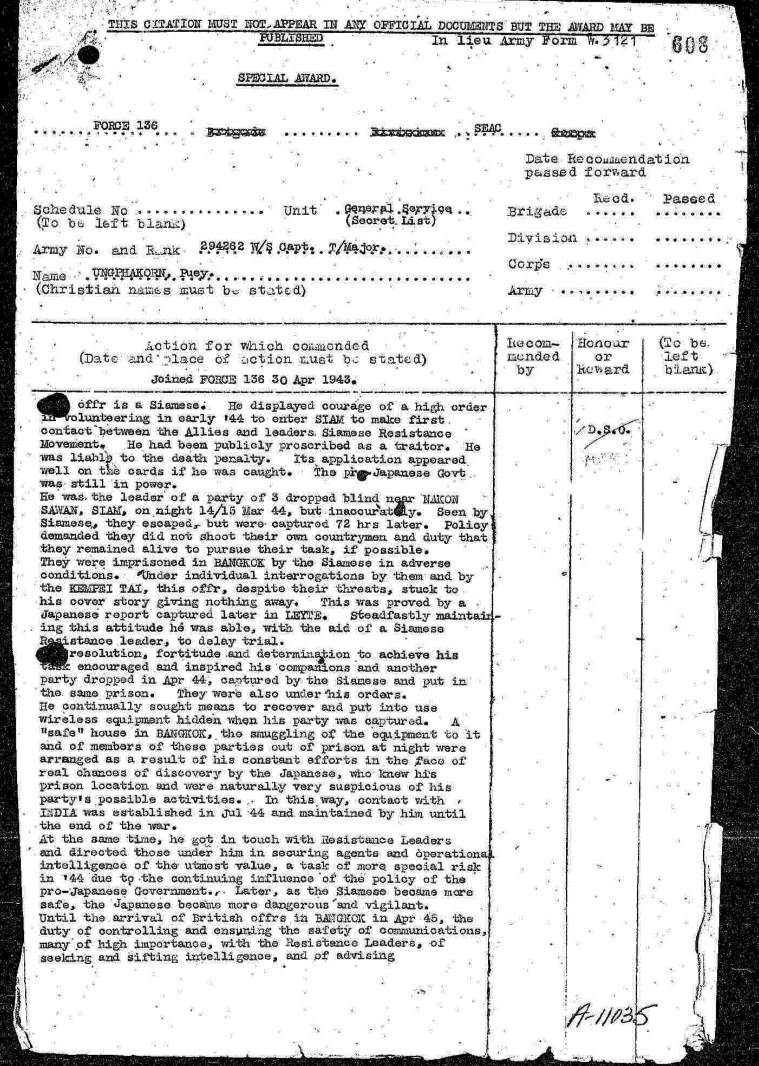

In the middle of March 1944, Puey was a leader of a team of three in Force 136 that parachuted into a region near to Nakon Sawan in North Thailand. The operation was known as ‘Operation Appreciation’ (HS 1/55). Its objective was to make contact with Pridi Banomyong, who served as Regent to the young monarch, and who was also working secretly as a leader of the anti-Japanese underground movement in Thailand. Puey’s team was also tasked with establishing wireless and telecommunication contact with India, as well as reconnoitering a suitable drop zone for subsequent intelligence gathering (HS 1/56).

Unfortunately the team dropped inaccurately and Puey and his team were captured 72 hours later. They were then transferred to Bangkok and interrogated individually by the Japanese secret police (Kempeitai). Despite threats, Puey and the team stuck to their cover story and gave nothing away. With the help of Luang Adul (Thai Head of the Police) who was secretly working with the Free Thai Movement in Thailand, Puey and his team were able to conduct intelligence gathering missions at night under the noses of the Kempeitai. As a result of this audacious act, the line of communication between the Thai resistance movement and the Allies was established.

Puey Ungphakorn and his team were subsequently recommend for an Award of Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE).

Notes:

Siam was renamed Thailand in 1939, but both terms are often used interchangeably in official documents up to about the 1960s.

Further reading and online resource:

E Bruce Reynolds, Thailand’s Secret War OSS, SOE and the Free Thai Underground during World War II (2010)

Puey Ungphakorn, A Siamese for all seasons: Collected articles by and about Puey Ungphakorn (1981)

Sawat Sisuk, Seri Thai remarks on ‘Operation Chamkad Balankura’ and some military operations (1995)

Pear Maneechote and Jasmine Chia, An Oral History of the Seri Thai, Thai Enquirer, (September 23, 2020)

Good to see one of the lesser-known parts of the SOE story brought into the limelight.

Imperial War Museums has a number of items (particularly photographic images) relating to Force 136.