As part of National Volunteers’ week, I’d like to celebrate with you the recent completion of a volunteer cataloguing project.

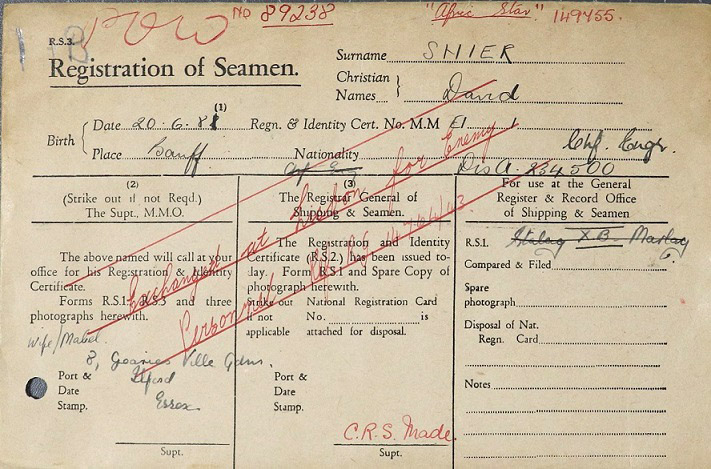

The series BT 373 Merchant Seamen Prisoner of War Records, Second World War, comprises 3,333 individual records of merchant seamen. Technically speaking they were internees, but the records use the terms ‘prisoner of war’ and ‘internee’ interchangeably in this series. The records are stored in envelopes, known as pouches, and contain information gathered by, or passed across to, the Registry General of Shipping and Seamen. The records were transferred in 2000 but with minimal information, providing only surname and first name or initials. To this data we have now added the information from within the pouches.

The pouches hold cards and paperwork relating to each internee. The cards record the name of the internee and their rank or capacity, their date and place of birth, the name of the last ship they were on, and often the date it was captured or sunk and the ship’s official number. The cards also record the camp they were interned in, and the name of any subsequent camps, the name and address of next of kin, and their internee or prisoner of war number.

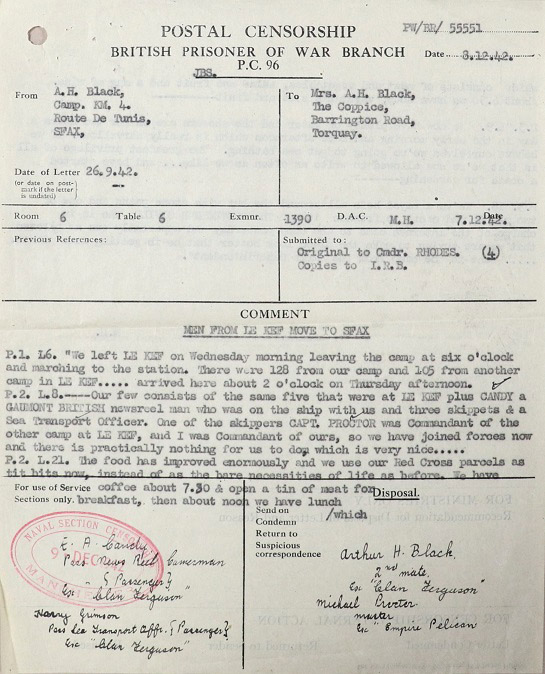

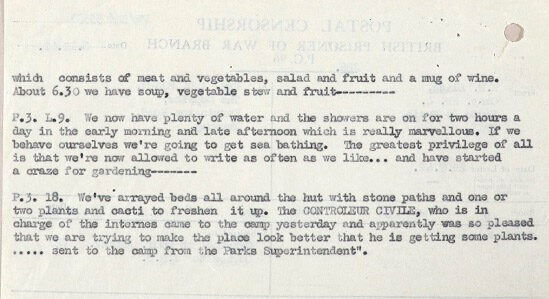

Very often, along with the cards there is additional paperwork. Sometimes this is in the form of letters to and from the internees, which were intercepted by the Postal Censorship Department, Prisoner of War Section, and the appropriate segments of the letter were copied and sent on to the departments to which the intelligence would be useful. While it can be very frustrating having only parts of a letter, they can provide a valuable insight into life at various internment camps, the treatment of internees, the circumstances of their capture, and their hopes and expectations for release under prisoner of war exchange programs.

William Robert Hewitt, was a fireman and trimmer on board the Clan Ferguson when it was sunk off the coast of North Africa on 12 August 1942. He was interned at Bastion IV, El Kef, Tunisia, and wrote the following letter home:

‘It was hell on earth this time. 12 August it happened. We all went straight over the side into the water. I was picked up on the 13th by a raft then I spent 4 days on that before we arrived here. I have no clothes left. If you haven’t heard one way or another what money they are going to give you let me know. You should get about £3 a week even though I lose the £12 a month. It was suicide trying to get where we were going. I would have been better off missing the shop and going to jail, at least I would of known when I was coming out, but here I don’t know when, I will be home. While I’m here I get a parcel of groceries every ten or twelve days and I make that do me. I can’t eat the food they give us it isn’t what we are used to.’

Arthur Huntington Black, Second Mate on the Clan Ferguson, writes home in very different terms. On 29 September 1942 he sends the following to his wife in Torquay:

‘We left Le Kef on Wednesday morning leaving the camp at six o’clock and marching to the station. There were 128 from our camp and 105 from another camp in Le Kef. Arrived here [Sfax] about 8pm on Thursday. Our few consists of the same five that were at Le Kef plus Candy, a Gaumont British newsreel man who was on the ship with us and three skippers and a Sea Transport Officer. One of the skippers, Captain Proctor was commandant at the other camp at Le Kef, and I was Commandant of ours, so we have joined forces now and there is practically nothing for us to do, which is very nice. …The food has improved enormously and we use our Red Cross parcels as tit bits now, instead of as the bare necessities of life as before. We have coffee about 7.30 and open a tin of meat for breakfast, then about noon we have lunch which consists of meat and vegetables, salad and fruit and a mug of wine. About 6.30 we have soup, vegetable stew and fruit. … We now have plenty of water and showers are on for two hours a day in the early morning and late afternoon which is really marvellous. If we behave ourselves we’re going to get sea bathing. The greatest priviliege of all is that we’re now allowed to write as often as we like … and have started a craze for gardening. We’ve arrayed the beds all around the hut with stone paths and one or two plants and cacti to freshen it up. The Contoleur Civile who is in charge of the internees came to the camp yesterday and apparently was so pleased that we are trying to make the place look better that he is getting some plants sent to the camp from the Parks Superintendent.’

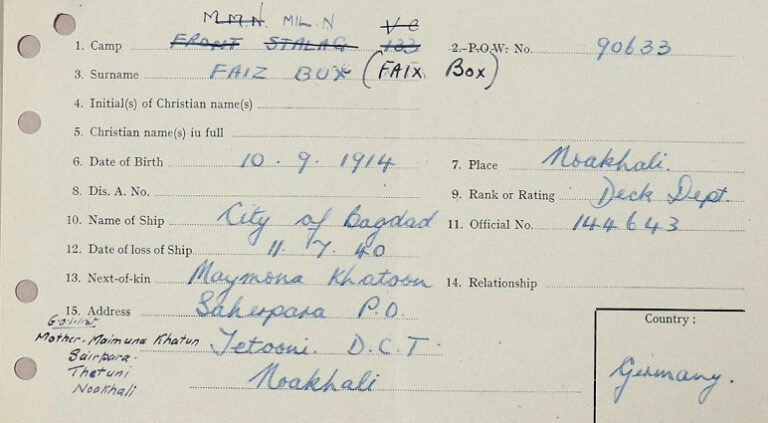

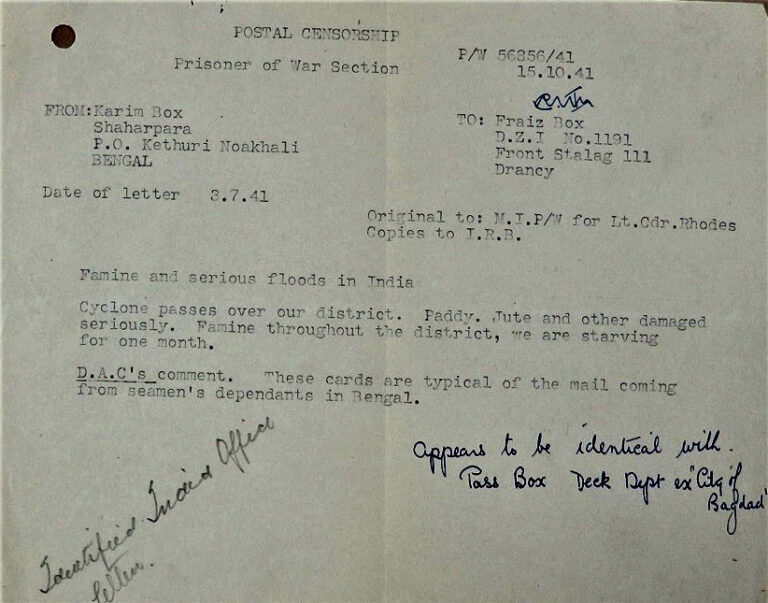

453 of the internees were listed as Indian, with the majority coming from Sylhet, Noakhali and Chittagong, which are now part of Bangladesh. This evidently caused a naming problem, as there were several variants of the first and last names of the seamen. For example, BT 373/3307 Faiz Bux is also noted in the cards as Fraiz Box and Fayz Box. Also, with a lot of popular first names and last names, the name of the father would be written in, such as Rahman, Ahmad, son of Abdul Kader. On the original paperwork ‘son of’ had been abbreviated to ‘x’ but we decided to put this in full on the catalogue, to avoid any misunderstanding.

A lot of the letter extracts in the pouches of Indian merchant seamen refer to a lack of news and fear for their relatives back at home. Very often, with the main breadwinner interned, and with seaman’s allotment payments being meagre or non-existent, families were left in severe poverty. Nabin Rame was a Topass on board the Tribesman, which was lost in December 1940 and was interned in Germany in Marlag und Milag Nord. The Postal Censorship Department made the following notes from a letter from his wife:

‘Writer states that she is at present living in great poverty and wretchedness, living only on a bare pittance of £12 per month with her sons, she says everything in Calcutta is becoming dearer and dearer, an ordinary sari costs about £6 or £7. Flour sell at 2 surs a Rupee, Rice is also 2½ surs a Rupee, Writer finds it very difficult to live on her bare monthly pension of £12. States in her letter we are all dying of poverty, hungry, want, and nakedness.’

In some parts of India this situation was made even worse by natural events. In 1941 a cyclone hit Bengal causing severe damage to buildings and crops. Faiz Bux, who was interned at the time in Front Stalag III in Drancy, received the following news from a relative in Noakhali:

‘Cyclone passes over our district. Paddy, Jute and other damaged seriously. Famine throughout the district, we are starving for one month.’

To which the Censorship Officer has commented:

‘These cards are typical of the mail coming from seamen’s dependents in Bengal.’

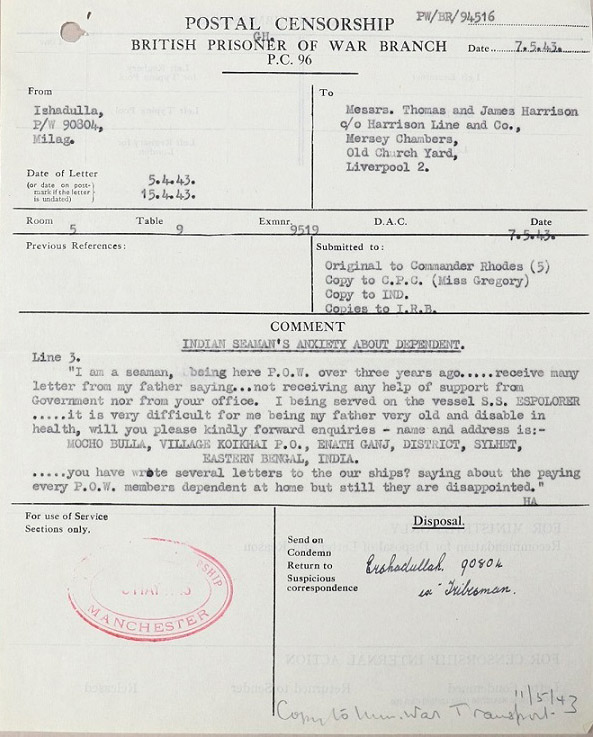

Many merchant seamen wrote letters complaining that their families received no subsidies whatsoever from the shipping companies for which they had worked when they were captured. On 5 April 1943 Ershad Ullah from Sylhet, East Bengal, a coal trimmer interned in Stalag XB Marlag, wrote to his employers Messrs Thomas and James Harrison, of Harrison Line:

‘I am a seaman, being here POW over three years ago … receive many letter from my father saying … not receiving any help of support from Government nor from your office. I being served on the vessel SS Explorer … It is very difficult for me being my father very old and disable in health, will you please kindly forward enquiries … You have write several letters to the our ships saying about the paying every POW members dependent at home but still they are disappointed.’

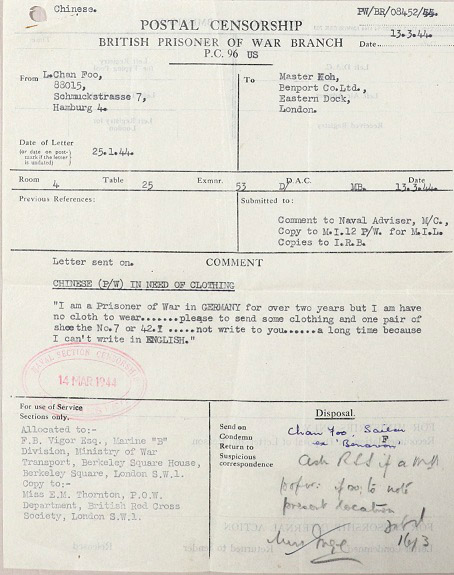

291 interned merchant seamen were from China, usually from Canton (Hong Kong), Macao or Hainan. Most were interned in Marlag und Milag Nord, but were transferred late in 1943 as ‘free workers’ to Arbeitlagers in Hamburg and Magdeburg. There they would work either in Chinese laundries or on board German steamships in port. Hamburg was not a safe place for the Chinese community who had settled there. They had no medical care and were very much confined to the poor quarters of the city.

On 21 January 1944 Chan Ah Foo, formerly a seaman on board the Benavon, who had by then been moved to Schmuckstrasse 7, Hamburg, wrote to his employers:

‘I am a Prisoner of War in Germany for over two years but I am have no cloth to wear … please to send some clothing and one pair of shoes size 7 or 42. I not write to you a long time because I can’t write in English.’

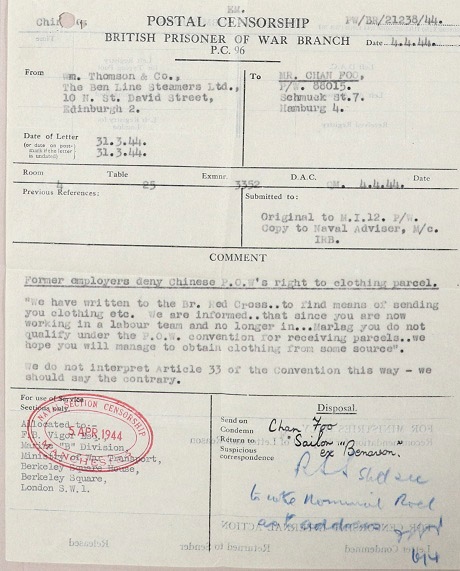

On 31 March 1944, William Thompson and Co, owners of the Ben Line Steamers, Edinburgh, reply refusing his request:

‘We have written to the British Red Cross to find means of sending you clothing etc. We are informed that since you are now working in a labour team (Chan was moved from MMN to a Chinese Arbeitlager in Hamburg, and then to a Chinese laundry in Hamburg) and no longer in Marlag, you do not qualify under POW convention for receiving parcels … we hope you will manage to obtain parcels from some source.’

There are also pouches for merchant seamen interned in Japan, including those who died in captivity and those who were executed either on board their own ship, or on the Japanese ship to which they had been transferred. Some prisoners of the Japanese were also held captive in Hong Kong and in Singapore. What is abundantly clear is that the Japanese authorities regarded merchant seamen as belligerents rather than as civilians, and treated them accordingly, with as little regard as they held for captured military personnel.

For those born less than 100 years ago, additional information will be added to the catalogue 100 years after the date of birth. At the moment, for data protection reasons only name, year of birth, certificate number, name of last ship and date of loss of ship show up for those born after 1920. The year after the 100th birthday information about place of birth, full date of birth, rank or capacity, camp last interned in and prisoner of war number will be added to the description. Where the year of birth is not known the latest date in the series (1927) will be used to release the additional catalogue information.

The BT 373 merchant navy project started in October 2019 with nine volunteers, all cataloguing the records directly on site at Kew. By lockdown in March 2020 there were only six boxes left to complete or 233 Merchant Seamen. The spreadsheet entries were completed by March 2021 and went live on Discovery, our online catalogue, in April 2021.

I am very grateful to my wonderful volunteers who worked very hard, and with great dedication, to get this project completed on time. Thanks to their hard work, this level of cataloguing will make it far easier for family historians to find details of a relative, and also for military and social historians, given the range of content in the pouches.

To find out more about volunteering at The National Archives click here.

This is excellent work. Little is written and known about MN internees during the war and less so about Chinese and other ethnic seafarers serving on British flagged vessels during the war period.

I found a record of several “distressed seamen” arriving at Liverpool from Algiers in 1943. They are listed as previously being in Germany. Did the Germans release internees before the end of the War?