Content note: This blog includes an extract that describes witnessing the shooting of defenceless soldiers.

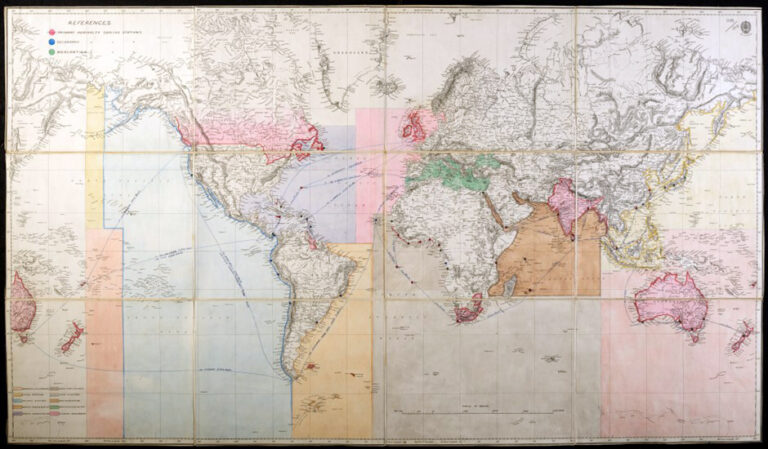

During the 19th century, the need for Admiralty Foreign Stations arose due to the expansion of European powers’ colonial empires and the increased global trade that resulted. These stations were established by the British Royal Navy to maintain a permanent naval presence in key locations around the world.

The Admiralty Foreign Stations were particularly important in securing and protecting the British Empire’s interests in areas such as Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. They were also vital for responding to crises and conducting operations in remote areas of the world where the British Navy needed a permanent naval presence.

In addition to their military role, Admiralty Foreign Stations also played an important diplomatic role. They served as centres for British diplomacy and influence in local affairs.

In this blog, we will explore the First Sino-Japanese War between 1894–95, through the lens of the records in Admiralty China Station (ADM 125/112-114). This station was made up of three main bases in Hong Kong, Singapore and Wei-Hai-Wei (now Weihai). These records provide a unique and valuable perspective on the First Sino-Japanese War. They include correspondence, reports, and other documents related to the activities of the British naval forces stationed in China during the war.

Through these records, we can gain insights into the naval operations of both Japan and China, as well as the role of the British navy in the conflict. We can also see how the war impacted the economic and political landscape of the region, and how it set the stage for future conflicts and power struggles in East Asia and its lasting impact on the region and the world.

Cause of the First Sino-Japanese War

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 was a conflict between the Qing Dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan over control of Korea and influence in East Asia. The war had significant implications for both countries and for the region as a whole, as it marked a shift in the balance of power in East Asia and the emergence of Japan as a major regional power.

Both China and Japan viewed Korea as strategically important, as it provided access to important trade routes and markets. Japan sought to establish control over Korea in order to secure its own economic and strategic interests, while China sought to maintain its own influence over the peninsula. Control over Korea was seen as key to gaining dominance in the region.

Outbreak of the war

During the 19th century, Korean society was characterized by poverty, oppression by the ruling class, and peasant uprisings. In 1893, a significant movement was organized by the Tong-Haks rebel peasant army against the ruling Joseon Dynasty and its King, Gojong. The movement threatened to invade the Korean capital Seoul, take control and drive the Japanese and all foreigners out of the country. This led to the Japanese and Chinese governments sending warships to prepare for emergencies, but the rebels were dispersed by the Korean soldiers and the matters quieted down for a time.

The Tong-Haks regrouped in the Spring of 1894 and managed to defeat Korean government troops, then proceeded to Seoul. At this time, the future president of the Republic of China, Yuan Shikai, was living in Seoul as an imperial resident. Seeing the situation was becoming critical, he feared Japan would use it as argument for intervention, something he wanted the Chinese government to do. However, to justify Chinese involvement, he needed the King of Korea to formally request support from China to restore order.

By the end of May, Yuan successfully got what he wanted: A written request from King Gojong for the intervention of China. On 5 June 1894, about 1,500 Chinese troops from Tientsin landed at Asan, some 50 miles from Seoul. Before they landed, a notice of their impending arrival was sent to the Japanese government.

Wanting to influence the unfolding power struggle themselves, Japanese troops arrived and demanded reforms and privileges from the Korean government. Tensions increased and the first shot between Chinese and Japanese forces was fired in July 1894, leading to Japanese troops breaking into the Royal Palace and taking King Gojong under their guard.

The Battle of Pungdo and the Kowshing Incident

After King Gojong was detained on 23 July, the Japanese Imperial Army then seized the Chinese Legation, took control of all telegraph wires, and proclaimed a military occupation of Seoul.

In the midst of this, on 25 July, the first naval battle of the First Sino-Japanese War took place between the Japanese Imperial Navy and the Chinese Beiyang Fleet off Asan.

The battle ended with Chinese vessels either sinking, being wrecked, surrendering, or escaping. One of the casualties was the British-registered Kowshing, which was chartered by the Chinese Beiyang Fleet to convey 1,200 Chinese troops to Korea.

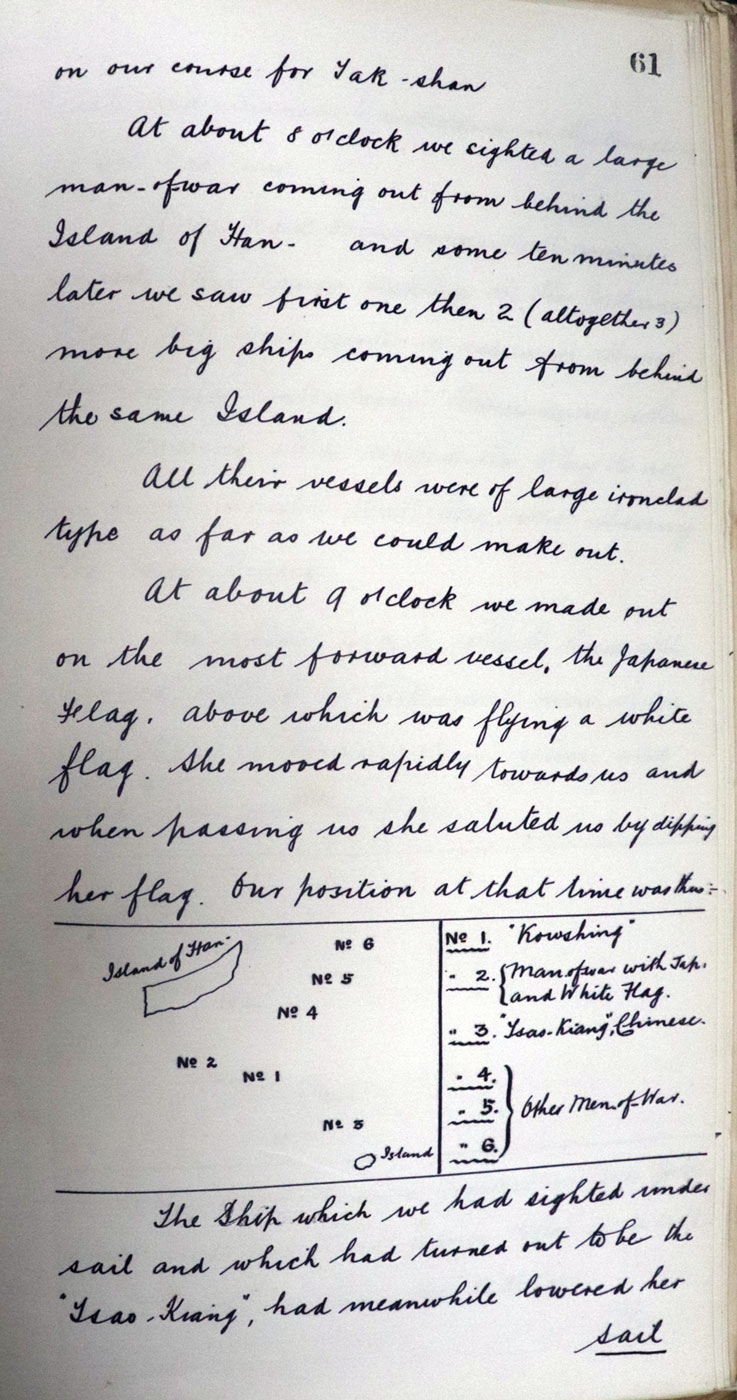

The Kowshing was intercepted and sunk by the Japanese warship Naniwa, command by Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō. Kowshing commander Captain Thomas Ryder Galsworthy, and a few British crew members, together with a German military adviser to the Chinese Government Constantin von Hanneken, were rescued by the Naniwa after swimming to safety. But 1,000 Chinese soldiers jumped into the water and were fired on by both the Japanese and by the Chinese on the sinking ship. This event was vividly depicted by the evidence provided by Constantin von Hanneken to William Henry Wilkinson, British Vice-Consul at Chemulpo:

I swimming, I saw the ship going down, she went stern first, during this the firing continued, which was bravely answered with rifle by the poor wretches, who knew they had no chance in trying to swim. I saw a Japanese boat lowered heavily armed with men. I thought they were coming to the rescue of the swimming men, but I was sadly mistaken, they fired into the men on board the sinking ship. I do not know what their purpose was in doing so. The fact is that the swimming men were fired at from the Japanese man-of-war and from the sinking ship. The men onboard the latter one, probably having the savage idea that if they had to die, their brothers should not live either.

Evidence of Constantin von Hanneken describing the loss of British Steamer Kowshing, 25th July 1894.

Catalogue ref: ADM 125/112 folios 60-71

The sinking of the British steamship Kowshing had a direct impact on the fighting on land, as the Chinese reinforcements failed to reach their intended destination due to the Japanese victory. This led to the subsequent Battle of Seonghwan, where the outnumbered and isolated Chinese detachment was defeated. Formal declarations of war were made 1 August 1894.

The sinking of the Kowshing by the Japanese navy led to protests and demands for compensation from the owners, and a negative response from the British public. However, calls for Japan to pay an indemnity ceased after British jurists ruled that the action was in conformity with international law. The sinking was also cited by the Chinese government as one of the ‘treacherous actions’ by the Japanese in their formal declaration of war.

I believe my husbands 3x Great Grandfather was on the vessel “Kowshing” is there anywhere on the web that I would be able to view the above document (Catalogue ref: ADM 125/112 folios 60-71) I have seen his name mentioned on another website about the Kowshing but have never seen the handwritten document above and would be interested to read it. I live in Australia so cannot visit the National Archives.

Dear Sharon,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.