Personal power in peace and war

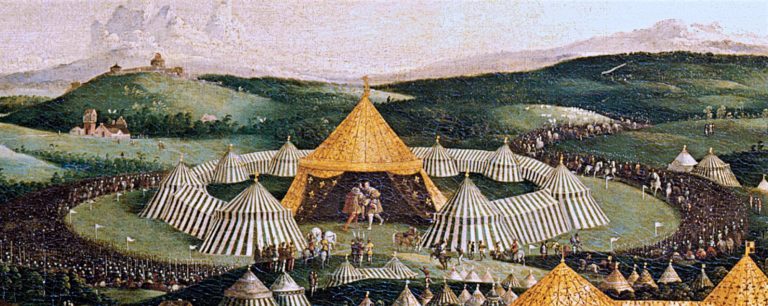

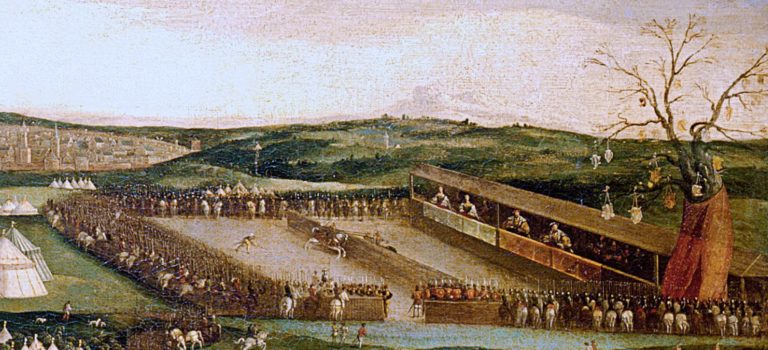

On 9 June 1520, Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France put on their dazzling armour and led out teams of jousters to begin two weeks of competition in a grand tournament celebrating peace between their two countries. The kings had met in person two days previously in a magnificent tent decorated with gold cloth and tapestries. The location was near Guisnes Castle, just inside English-controlled Calais – an 86-square mile area surrounding that remnant of England’s medieval lands in France.

At their first meeting, Henry and Francis rode towards each other with their hats raised, dismounted and then embraced as brothers. Every effort was made to impress in all aspects of their appearance. Their highly fashionable jewelled clothes shone with gold and silver thread, and all other aspects of their demeanour were scrutinised – from the bearing of their horses, to the banners on display, the quality of their companions and even the physical appearance of their guards (Henry’s carried gilded spears). This display of splendour was the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

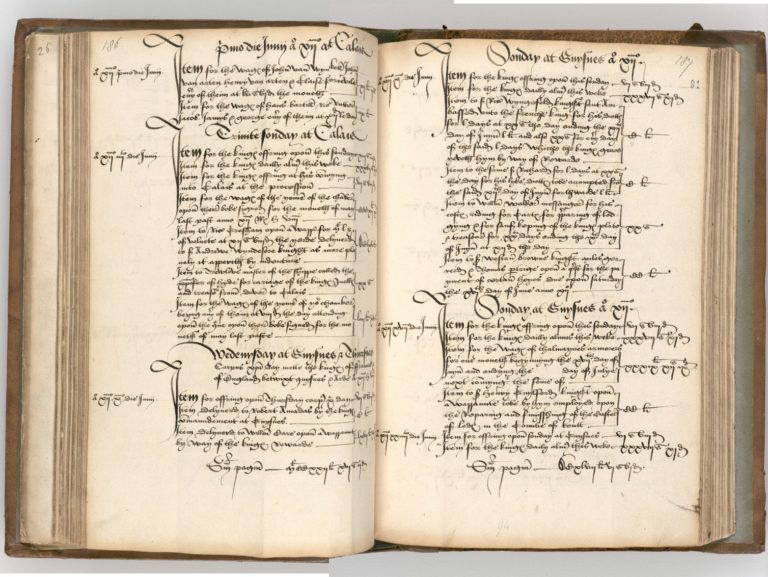

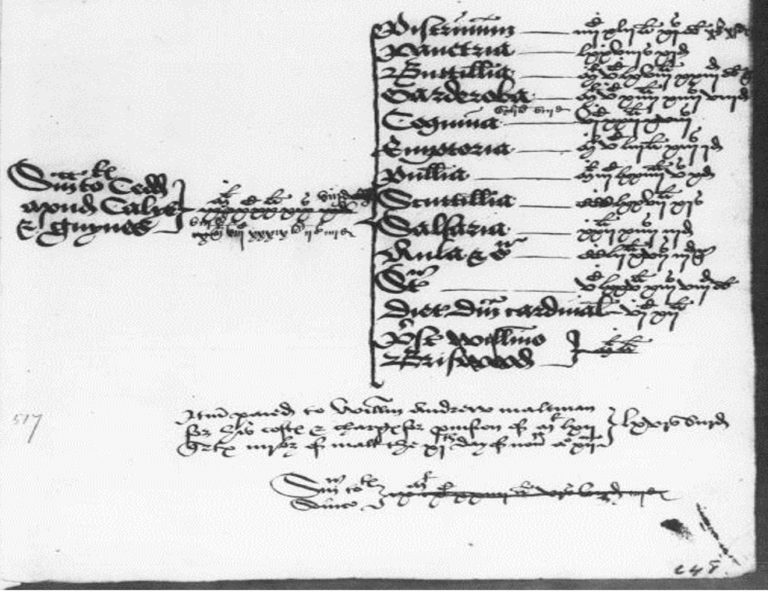

Henry VIII and Francis I met at a temporary town of tents and portable buildings created to shelter them, house courtiers, host meetings, offer banquets and dances, and accommodate thousands of servants. All the trappings of their outlandish wealth supported days of mock combat through to 24 June. We know what took place and what it cost the English from the records of the king’s chamber. The colourful report by the chronicler Edward Hall supplies excellent detail, and a picture, painted perhaps 20 years later, remains an important visual reference.

A king in search of glory

Henry VIII came to the throne aged 17 in 1509, backed by national enthusiasm for a return to dynamic kingship. Modelling himself on Henry V, he was eager to recover English lands in France, and to correct the recent failures of expeditions in 1475 and 1492.

For five months, from June 1513, Henry campaigned in northern France. He won a minor victory at the Battle of the Spurs on 16 August, and by the end of September had captured Thérouanne and Tournai. He was also in a stronger position (though annoyed to have been absent), when France’s ally, James IV of Scotland, died alongside most of his nobles at the battle of Flodden on 9 September.

The 1513 war with France and Scotland was also part of a series of alliances to contain wider French aggression. In 1494, they crossed the Alps to claim the kingdom of Naples. England stayed out of the resulting Italian wars until October 1511, when Henry VIII joined the pope’s Holy League to protect papal lands. This move opened up other ways for Henry and his leading adviser, Thomas Wolsey, to exert England’s influence.

Achieving and celebrating peace

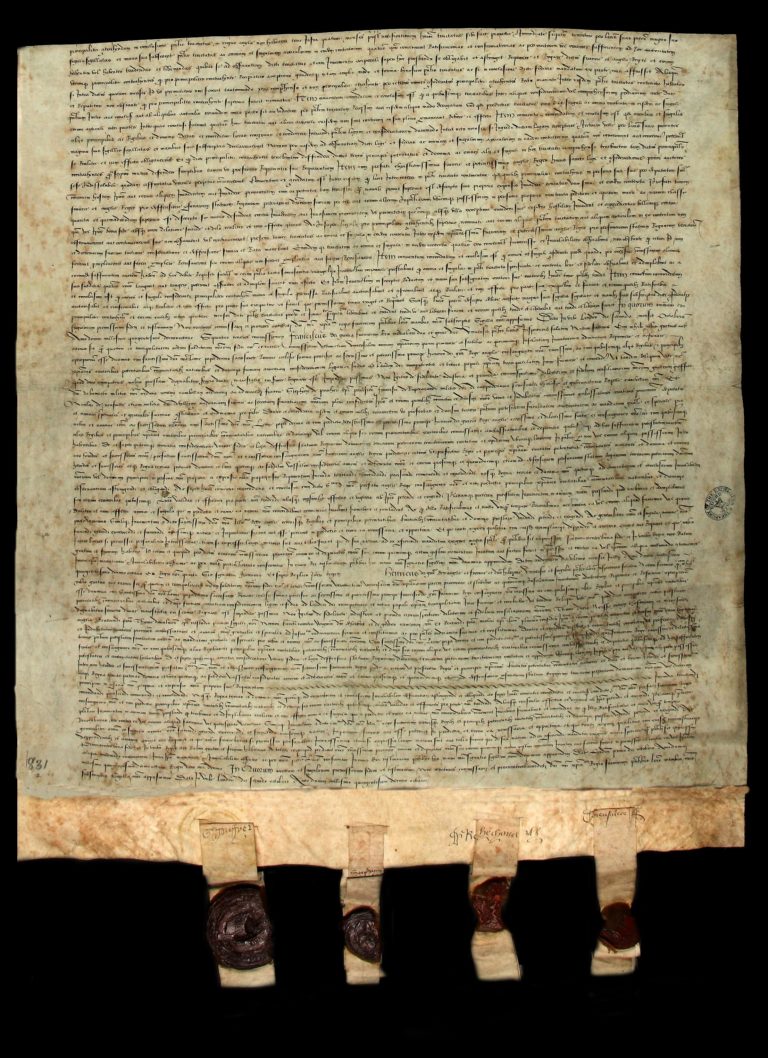

Leo X was desperate to be the pope who persuaded European rulers to join a crusade to halt the westward expansion of the Ottoman Empire. By 1518, the costs of rebuilding and running Tournai as part of England prompted Henry VIII to sell it back to France. Wolsey led these negotiations, and as the pope’s personal legate in England, he took the opportunity to broaden talks towards a permanent accord in Europe.

His efforts underpinned the Universal Peace agreed between the pope, England, France, and Burgundy/Spain in London in October 1518. Beneath the grand plans were the details of the Anglo-French agreement. They included a marriage treaty between Henry’s daughter Mary and the French Dauphin. A personal meeting within two years between the English and French kings would be a spectacular ratification of this alliance.

This peace was a moment of optimism, but it also revealed competition and suspicion between Henry VIII (b. 1491), Francis I (b. 1494), and Charles V, ruler of Spain, Burgundy and the Netherlands (b. 1500). All three took power between 1509 and 1516. All were educated in the new humanist learning that printed rediscovered classical texts for the first time. They had similar outlooks, but competing aims in safeguarding their personal and national interests. The Field, therefore, served the political end of peace through demonstration of preparedness for war. Although Charles was not involved, he moved his court to the Burgundian frontier a few miles from the Anglo-French gathering, and met with Henry before and after the event.

Prolonged preparations

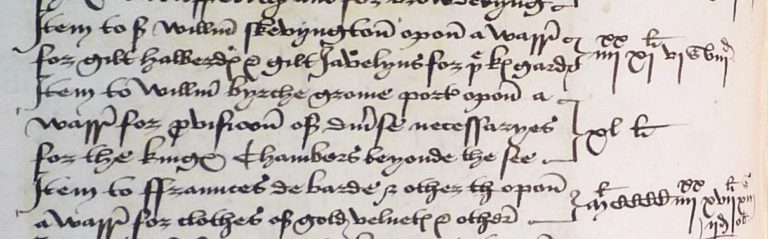

The meeting lasted for a little over two weeks but required over a year’s worth of intensive preparation. The records of the king’s chamber reveal the small army of carpenters, glaziers and painters preparing the site at Guisnes. The English purchased weapons, staves and accessories and adapted them for tournament fighting – a process that included blunting, lightening and hollowing swords, lances and axes. A workshop at Calais supported teams led by 24 armourers on constant duty to maintain the flow of equipment. Similar effort from the stable department sought horses from around Europe.

Of great interest at the time was Henry VIII’s portable palace, described as ‘the king’s building’. Built outside of the gates of Guisnes, it had four blocks of rooms around a central courtyard over two floors, with an elaborate staircase and an endless wine fountain. The walls were brick up to about eight feet and then timber framed up to 30 feet. Similar to other campaign buildings like bakeries and breweries, it was built in sections in England and shipped to its destination.

The tournament

The centrepiece of the Field was the military competition between the knights of both nations. Between 200 and 300 English and French courtiers clamoured to fight in one or more of the three competitions – jousting individually with lances across a barrier or tilt; on horseback in the mêlée of the tourney; and on foot at barriers. Each element had its own rules on armour, weapons, point scoring, penalties and procedure. Opportunities to fight were managed carefully to allow all skilled fighters to have their chance.

On 9 June, Henry and Francis became co-leaders of a jousting team of defenders to compete over the next ten days against 14 teams of ten or 12 attackers. No fighting took place on Sundays or saint’s feast days and on 11 June, queens Katherine of England and Claude of France took their places as the chivalric focus for the fighting.

Henry and Francis both rode in the lists that day and broke many lances to great acclaim. Challenges in wrestling and archery filled days either side of a storm on which smashed down many of the tents on Wednesday 13 June. Francis seemed uninterested in seeing the English skill with the longbow, but he might have got the better of Henry in a wrestling match – although only a French commentator noted it.

Henry had prepared himself well for the foot combat on the final days of the meeting. His armourers at Greenwich had made him a body-hugging suit of articulated armour that offered complete protection. Francis insisted that the fighting on foot should be at the barriers rather than on the open tourney ground as Henry had expected. A replacement armour, with the required flared armoured skirt or tonlet, was dispatched quickly from England.

Hospitality on display

As hosts, the English could spare no expense in the supply of food and drink, entertainments, dances, and other distractions, which included a flying pyrotechnical dragon kite that swooped down on the royal couples as they left a final mass on Saturday 23 June. As many as 12,000 people dined over the two weeks that the Field lasted. The provisioning costs to the English royal household were at least £7,400 (perhaps equivalent to £4 million today).

Formal banquets were mixed with smaller scale personal meals to ensure that the kings and queens dined as equals. Masques and dancing reached the highest levels of fashion and sophistication in costume, music and refreshments. Even the departure ceremonies on 24 June featured the worthies and heroes of antiquity offering inspiring rhetoric on chivalry, ancestry and peace.

Formal and personal exchanges of expensive gifts backed up these themes. From horses to gilt and jewelled plate, both kings and queens ensured that the golden theme continued. All of this contributed to the colossal total cost of around £35,000 for the English.

Was it worth the expense and effort?

Francis was confident that the event confirmed the superiority of French power. He demonstrated this on 17 June, when he rode with a few companions into English territory and demanded entry into Henry’s chamber in Guisnes Castle. Once admitted, he helped Henry to dress. This episode appeared to be an act of friendship and trust, but it was an assertion of his right to invade the national and personal space of his royal rival.

The Field might have put England fully into the European diplomatic picture, but it only paused the rivalries between Charles and Francis in Italy. Over the winter of 1520-21, conflict flared once more and all states thought about how they would align. Despite Wolsey’s efforts, the universal peace of 1518 dissolved by the summer of 1521. Henry’s firm alliance with Charles V against Francis was cemented by Charles’s visit to London in May-July 1522. A three-year war with France then followed, through which Charles became the dominant power in Europe.

After the capture of Francis at the battle of Pavia near Milan in 1525, Charles was almost over-mighty. Politics then turned once again, as Henry looked to rebuild an alliance with France to check the dominance of the Holy Roman Emperor.

The history of the Field reveals how both kings wished to be judged by their fellow rulers and their own subjects. Surviving records indicate England’s cultural resources and conventions around food, drink and hospitality. The Field was a brilliant interlude in the swirling political changes of the 1520s, as war and the emerging forces of the Reformation shifted the priorities of national leaders.

In an age of personal monarchy, the Field was important in establishing the direct connection that became a common anchor for Henry and Francis. Their troubled relationship continued in a pattern of alliance or hostility until they died within three months of each other at the start of 1547.

Full detail on the events discussed in this blog is found in the excellent study by Glenn Richardson, The Field of the Cloth of Gold (Yale, London, 2013).

What a great blog and fascinating collection of documents! This is so helpful for A level History students or indeed anyone interested in history. Thank you.

A very interesting and informative article. Do you have any references about Cornish tin miners bring at the Field who demonstrated Cornish Wrestling?

Only recently joined and what a surprise. Almost like reading a novel, but all our own history. Looking forward to more. Thank you.

Fascinating. My interest in this event was instigated by a Carnival band’s portrayal in Trinidad and Tobago in the 1950’sor or early 60s. The name stayed with me and I can now fully appreciate why it was chosen! It is still in the 21st century an unimaginably dazzling portrayal of pageantry and sumptuousness.

Thank you. A great blog for a layperson interested in English history who usually relies on historical fiction. The equivalent of £4,000,000 doesn’t seem that much today but it must have been a strain on the economy then.

I have known about the “Field of the Cloth of Gold” for many years, and have been lucky enough to see some of Henry VIII’s armour from this time. This article paints a greater picture of what happened – how it would have looked, the work that went into staging it, and the political background. It makes me want to find out more about this unique occasion, any suggestions on books etc?

Fascinating! Very interesting. Thank you?

That’s amazing. We are still talking about it today. I’m curious about the tree in the painting. It looks like an oak. It looks they dressed it in cloth. What are the objects hanging from the boughs? Thank you!

The tree was coated in gilt. Knights hung their shields on it if they wanted to compete. It was called the tree of honour.