The National Archives holds one of the largest collections of photography in the United Kingdom, estimated to be at over 8 million items, much of which was gathered as part of the record keeping activities of the British Government. These photographs depict a wide range of activities from numerous spheres of life, both domestic and foreign. I have been researching photographic albums found within the Colonial Office Collection (CO 1069).

Photographic albums were the primary media within which photographs were stored, collected, shared and viewed, and they were used routinely throughout the nineteenth century. The CO 1069 series was founded in late 1869, which corresponds with early photographic history. As such, the relationship between photographic albums and their function as a record is interesting, not only within the context of archival history and practice but also as a form of knowledge-making within colonial administrations.[ref]George Leveson Gower, Earl Granville (1815–1891), Colonial Secretary from 1868-1870, sent a circular to colonial governors in November 1869 requesting photographs be sent to the Colonial Office library (CO 129/44/139). Modern photography had been ‘invented’ only thirty years before with the near simultaneous announcements of Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), inventor of the Daguerreotype, a permanent silver image captured on a silver-coated copper plate, and William Fox Talbot (1800–1877), inventor of the paper negative.[/ref]

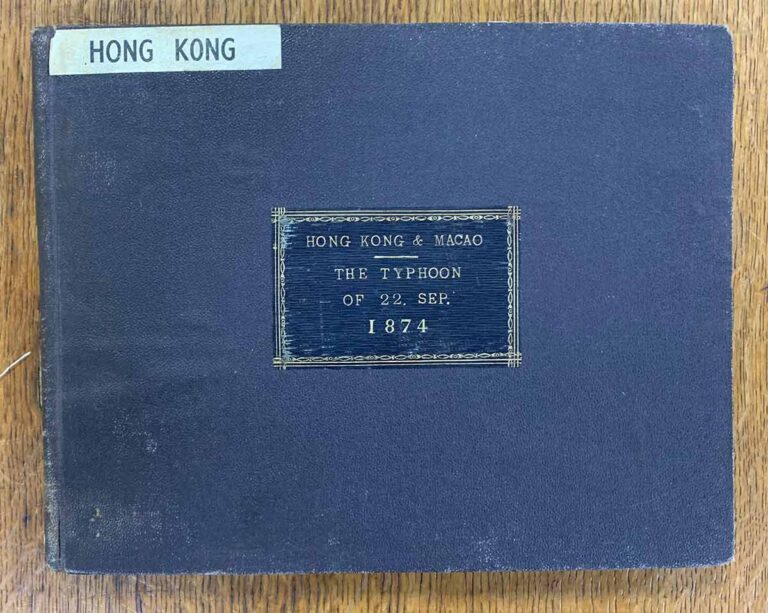

The image above shows one of the earliest photographic albums at The National Archives, titled ‘Hongkong & Macao, The Typhoon of 22 Sept 1874’. In this blog post, I outline why this album was produced and how it came to be part of the Colonial Office series.

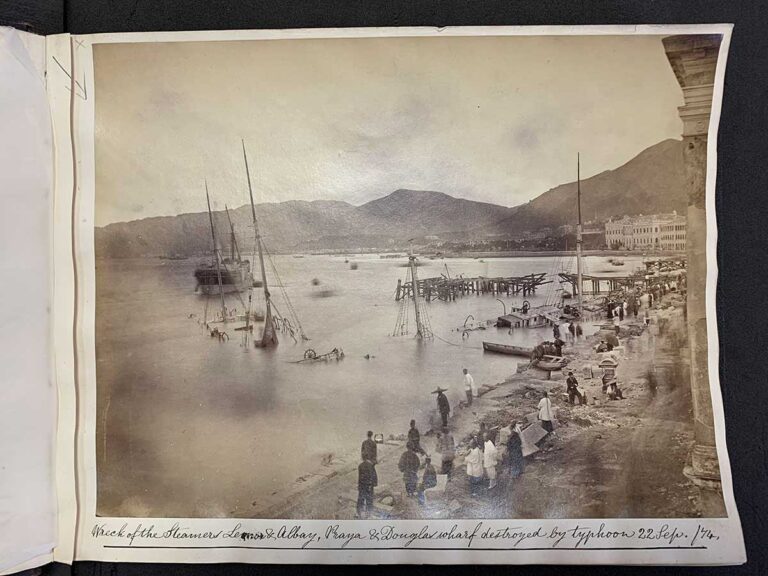

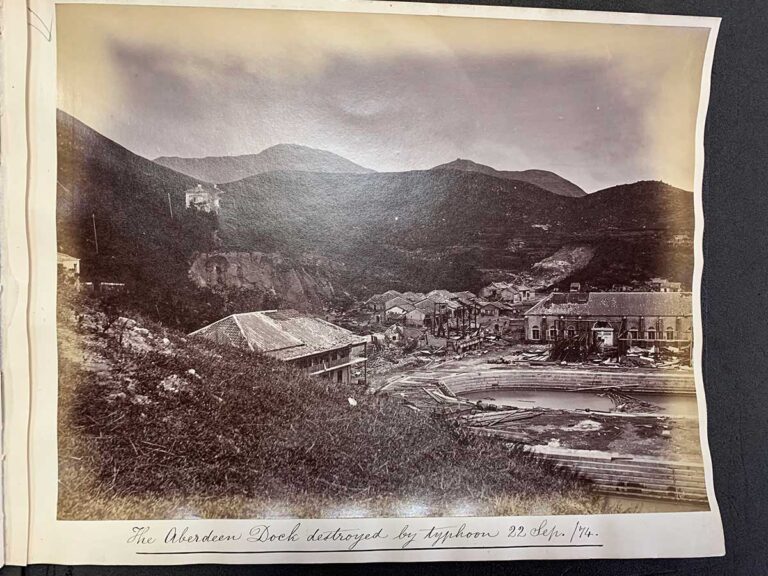

The album contains twenty photographs which record scenes in Hong Kong and nearby Macao after a devastating typhoon that raged between 22 and 23 September 1874, described as ‘the greatest calamity that has visited the crown colony since its establishment’.[ref]‘The Last Typhoon at Hong Kong’. Nature 11, 168–169 (1874).[/ref] Thousands of lives were lost, with Hong Kong and the surrounding areas suffering extensive damage. Documented in these photographs are scenes of devastation, which include stone buildings in ruins, huge boats captured listing on their sides, and homes destroyed by fire in the ensuing chaos.

Documenting disaster

In October 1874, Sir Arthur Kennedy (1809–1883), governor of Hong Kong, sent these photographs to the Colonial Office to accompany a report which documented how many lives had been lost and further described the extent of damage to the colony. Kennedy did not mention the photographer, or include further details about the photographs, merely noting that he had sent a ‘few photographs, illustrating some of the injuries done’.[ref]Catalogue reference: CO 129/168/77.[/ref] The photographs in this instance functioned as a visual document illustrating Kennedy’s report and were later sent to Queen Victoria (1819–1901) for her inspection.

What is notable about these photographs is that Kennedy did not commission the photographs, rather he bought them, readymade, from a Chinese photographer named Lai Fong (around 1839–1890), known colloquially as Afong.[ref]Chinese names are written with the family name first, followed by the given name. Lai’s family came from Gaoming in the Guangdong province, relatively close to Canton (Guangzhou), the former epicentre of the Chinese export trade. Where Lai Fong learnt photography is unknown, but records show that he worked at the José Joaquim Alves Silveira studio in Hong Kong in the mid-1860s. Terry Bennett, History of photography in China: Chinese photographers, 1844-1879 (London: Quaritch, 2013), p. 71.[/ref] Lai ran a successful photographic studio in Hong Kong and his talent for photography was noted by John Thomson (1837–1921), a Scottish photographer in Hong Kong at the time, who said that Lai had ‘exquisite taste and produces work that would enable him to make a living even in London.[ref]John Thomson, ‘Hong Kong Photographers, Part 1’. British Journal of Photography 19, p 569.[/ref] However, Lai’s talents lay beyond photography alone – he understood exactly the types of photographs that his market of primarily European and American buyers wanted.

Commerce and nostalgia

Producing ready-made photographs was common practice in Hong Kong and Lai, along with other photographers, stockpiled photographic views of the local area. Photographic views of Victoria harbour and government buildings, the racecourse and other areas of commercial interest were of particular interest to foreigners.[ref]So too were photographs of Chinese trades and Chinese ‘types’. Roberta Wue, ‘Picturing Hong Kong: Photography through Practice and Function’, in Picturing Hong Kong: Photography 1855-1910 (New York: George Braziller Inc., 1999), p. 31.[/ref] Life in the freewheeling port city of Hong Kong was highly competitive and difficult for those who sought to make a living there, and photographs were a popular way for foreigners to capture a sense of what was felt to be an intensely lived experience.

For Lai Fong and other photographers working there during this period, photography was both expensive, since materials and equipment had to be imported, and a laborious process requiring multiple stages to perfect both the negative and print. Ready-made inventories of photographs not only reflect a healthy demand for views of Hong Kong but also that a good financial return could be made if studios could produce, and sell, multiple prints from one negative. These prints were sold for three shillings and six pence each, a prohibitive sum for many of the Chinese residents in Hong Kong, many of whom were unskilled migrants.[ref]For comparison, contemporary records show that unskilled workers who worked as ‘chair-coolies’ earned roughly £1 a month.[/ref]

There is no record of how Kennedy acquired Lai’s photographs, but Lai’s press advertisements and studio labels from 1872 onwards often mention Kennedy’s patronage, evidence of not only a professional relationship between them but also Lai’s marketing skills as a trusted photographer for western customers.

Materiality and tactility

After the typhoon had passed, Lai set about photographing the aftermath, producing at least 44 collodion wet-plate negatives.[ref]Collodion wet-plate negatives were pieces of glass with a layer of light sensitive collodion mixture on its surface. This plate was then inserted into a camera ready for exposure.[/ref] Each negative could then be used to produce multiple albumen photographic prints, and the combination of collodion wet-plate negatives with the albumen printing process resulted in highly detailed and richly toned photographic prints that were extremely attractive.[ref]The albumen print was made by exposing paper (that had been made light sensitive with a coating of albumen and ammonia or sodium chloride) to daylight within a specially designed frame that held the collodion negative over the print so that the latent image would be transferred to the print, a process known as contact printing. [/ref]

Lai’s customers could either choose from a selection of prints, or they could buy ready-made sets in ‘neatly-bound’ albums with pre-printed captions.[ref]Bennett (2013), p. 71.[/ref] The binding used for ‘Hongkong & Macao, The Typhoon of 22 Sept 1874’ was added after it arrived in London and is comprised of a cloth material with embossed bubble grain pattern mounted onto board covers. Both the binding and the marbled end papers are typical of commercially available bindings of the time, reflecting the rapid industrialisation of book binding in the nineteenth century. The tactile nature of the binding, along with the addition of leather label with gold tooled lettering and border design, enhanced the perceived value of the photographs contained within it.

In the early period of photography in Hong Kong, many of the scenic views being produced of the colony were tailored for western tastes. In the case of Lai Fong’s typhoon photographs, both the cost and the subject matter of these photographs, largely focussed on the damage to British infrastructure, exemplify this. In fact, Lai’s typhoon photographs survive in many other collections around the world, which further demonstrates the popularity of these kinds of photographs. However, their arrival at the Colonial Office signalled their transition from the private realm of the local resident in Hong Kong, who sought to memorialise their lived experience in visual ways, and into the institutional life of the British government, where they were kept in the Colonial Office library to be used as reference materials for civil servants and officials. A new life for these photographs as bureaucratic document.

For further information on how you can search for photographs within this collection, read the research guide to photographs held by The National Archives.

Angela Cheung is The National Archives’ Research Fellow (Photography) funded by The National Archives Strategic Research Fund. Her research fellowship has focussed on the materiality of photographs found within the former Colonial Office library collection (CO 1069).

The V&A photography centre has a couple of videos about the wet collodion process, demonstrating the preparation of plates etc:

https://youtu.be/pNyQ0nfMsxo?feature=shared

https://youtu.be/MimSMblu64M?feature=shared

Dear Angela,

What a fascinating period of history, as one doesn’t normally see early photos of Hong Kong. Would it be possible to view the album in person or online? I am from Hong Kong, and would like to see part of my heritage. I was born during a typhoon and my family came out of it, which was very fortunate.