To help celebrate National Volunteers’ Week, this blog promotes the work of volunteers at The National Archives.

In 2021, the Cataloguing, Taxonomy and Data department started planning a volunteer project to work on improving the descriptions for records held in series C 115. This is how we began learning about Frances Fitzroy Scudamore Howard (known as Frances Scudamore), Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, of Holme Lacy, Herefordshire, and her unhappy fate.

Frances was the sole heiress of the Scudamore family of Holme Lacy, where she spent most of her life. She married Charles Howard, Duke of Norfolk, but their marriage was seemingly far from perfect, with the duke being absent most of the time and the duchess living as a recluse. In 1815, the duke died with no apparent heirs and the duchess became a very rich widow, combining the Scudamores’ fortunes with her late husband’s estates, rights and titles.

Not long after her husband’s death, the duchess was showing signs of poor mental health. An inquisition, held at The National Archives, was ordered to ascertain her state of mind and her properties (Catalogue Reference: C 211/17/N36). Her case was brought before the Court of Chancery, at the time the main court dealing with cases of persons deemed unfit to manage their estates.

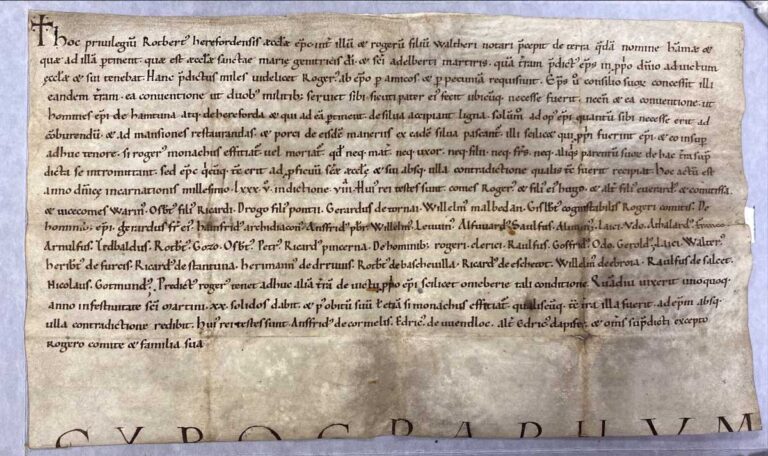

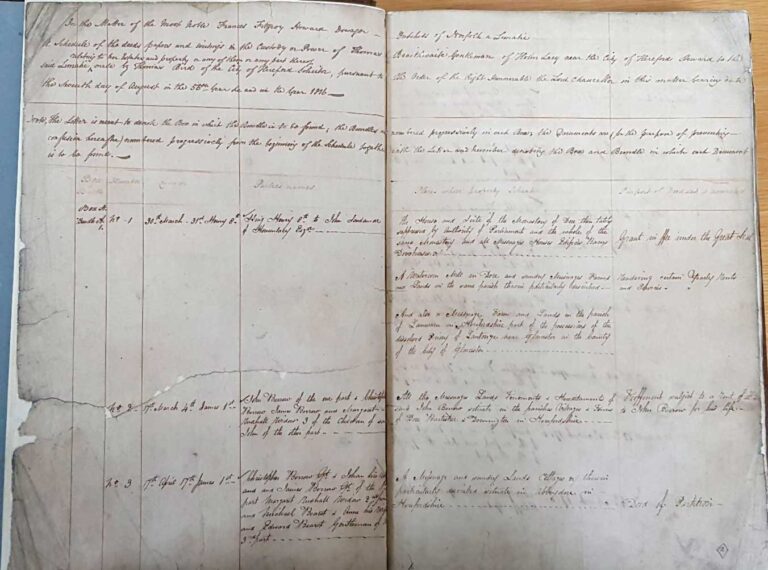

Thousands of deeds, papers and writings of various nature, including letters, cartularies, bonds and court rolls going back to 1085, were brought to court as exhibits in connection with her maintenance. The records entered the office of John Springett Harvey, Master in Chancery, and on the 7 August 1816, the Lord Chancellor instructed Thomas Braithwaite, steward of the duchess, to commission Thomas Bird, a solicitor, to compile an inventory of the documents.

The Chancery exhibits were later transferred to The National Archives and made available to the public in series C 115. The inventory compiled by Bird, known as schedule, is orderable as IND 1/23396.

To conclude Frances’ story, she died at Holme Lacy in 1820.

Our interest was piqued.

An ideal project

After viewing Bird’s schedule, we noticed that the entries were well structured. Each document was numbered, and the information given included the records’ dates, parties involved, subject matter and type of documents.

The schedule is place-name rich, capturing locations featured in the duchess’s papers – potentially useful to researchers interested in many topics, including family and local history. Places in Herefordshire, Monmouthshire and Gloucestershire are mentioned.

Following our findings, we put together a project to transcribe 8969 entries in the schedule covering the first 110 pieces – a large part of the series. We decided that this project could suit remote volunteers.

The handwriting was not too daunting, however it did include some abbreviations and legal terminology that would need deciphering. The volunteer’s task would entail transcribing the entries as they saw them in Bird’s schedule (from digital photographs sent to them) and copying the data into corresponding columns reproduced in a spreadsheet.

All we needed were volunteers willing to help us! We had a good response and at one point up to 10 people were volunteering with us.

We put together supporting guidance, including a document detailing places featured in the schedule and their alternative spellings, so that volunteers could determine modern equivalents to use in the descriptions. We circulated newsletters keeping volunteers informed of progress and shared transcription tips. Further details on how we collaborated with the volunteers can also be found in a previous blog post.

Bird’s schedule has been fully transcribed by the volunteers and the improved descriptions will be uploaded into our catalogue, Discovery, in the near future.

Our volunteers’ experiences

We thought it was a good time to reflect on the project and how important volunteer contributions are to The National Archives.

We asked our volunteers what made them participate in this project. One volunteer, Amy Grace Harris, said that they did so ‘to supplement [their] history degree and to gain insight into the work of the National Archives in terms of future career opportunities.’

Olivia Stockdale, another project volunteer, had several reasons for wanting to join it: ‘I wanted to gain more experience working with archives but didn’t have the time or funds to regularly commute to an archive. The project proved to be a fantastic chance to learn about … how to improve searchability [of records] (such as adding the standardised spellings of places and surnames in square brackets), whilst also learning more about the Scudamore family and their dealings over several centuries.’

We were curious to find out what the volunteers enjoyed most about collaborating with us. Olivia stated that ‘deciphering the various placenames, which involved first trying [to] read the 19th-century handwriting, and then working out what the modern equivalent of the place mentioned actually was (if there was one)’, is what she enjoyed the most.

‘Although time consuming, especially at the start of the project when I was less used to the writing and places mentioned, it was incredibly satisfying to finally work out the place mentioned… Legal terms could be similarly tricky, but I learned a lot more about the terminology of the different periods and the various activities the Scudamore family were involved in as well.’

Olivia Stockdale, project volunteer

Amy explained that ‘understanding the backstory of the Duchess of Norfolk and how her deeds came to be in the possession of the National Archives’ was something that they valued most when being on the project. They continued, ‘I have learnt how to transcribe more effectively and interpret historical documents. In addition, it sparked further research into property law and titles of the peerage.’

Also asked what skills she had gained, Olivia replied: ‘Working on the project was a great opportunity to learn more about archiving, and the transcription process was useful practice in maintaining attention to detail whilst working through detailed and often repetitive record entries. Both volunteer supervisors, Ada and Emily [Jennings], were hugely supportive throughout the process, and it was great to be able to work around my existing commitments whilst contributing to the project!’

We would like to conclude this post by thanking all the volunteers involved in the Duchess of Norfolk project. And big thanks to all past and future volunteers. Keep up the good work, the curiosity and the love for archives and learning!

Volunteering at The National Archives is a wonderful experience – you have the word of a former volunteer who enjoyed it so much that they never left.