Content note: This blog highlights documents that contain racist language and descriptions of the conditions faced by enslaved Africans. Original language is preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us fully understand the past.

Over the last few months, The National Archives has released over 8,000 new catalogue descriptions of documents related to the transatlantic slave trade.

We hold the records of the Royal African Company and its successor the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa. This collection is incredibly important nationally and internationally, as the Royal African Company transported more enslaved African men, women and children to the Americas than any other single institution in the history of the transatlantic slave trade.1

The new material has been added to the catalogue through a project funded by The National Archives Strategic Research Fund. Given their historical significance, the project has started to create a listing of all the records in the Detached Papers of the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa.

What are the Detached Papers?

The Royal African Company collection runs from 1660 to 1820 and has a range of sub-series, including letter books, minute books, ledgers and the Detached Papers. The Detached Papers are a collection of 94 boxes of miscellaneous, loose papers from 1750 to 1820. They mainly include letters, inventories, accounts, receipts and the personal papers of the governors and merchants of the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa, which was set up after the Royal African Company was dissolved in 1750.

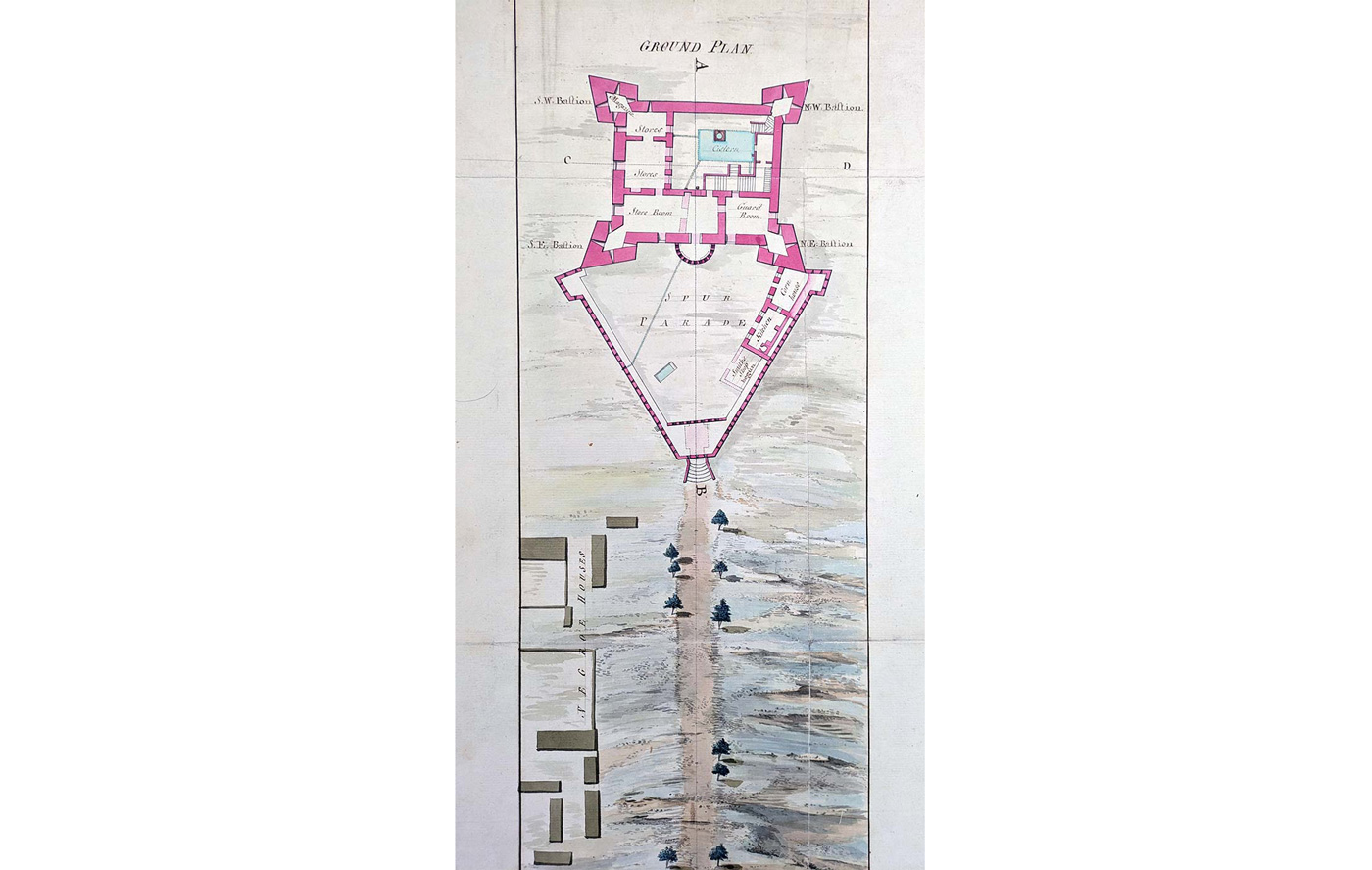

The Royal African Company received a royal charter in 1672, peaking in 1686 – when it embarked nearly 11,000 enslaved Africans on company ships in one year – it lost its monopoly in 1698 when individual traders were permitted to trade alongside them.2 When it was eventually dissolved, the company’s assets were transferred to the Company of Merchants. The company were provided with an annual parliamentary stipend to manage and operate the coastal forts and protect British trading interests in the region.

Cataloguing people, subjects, and dates

Until now, the Detached Papers were only listed on Discovery, our online catalogue, by box, with no indication of their contents other than the date of the material. Now half of the collection has been described at item level, describing persons, subjects and dates for each individual document in these boxes. This has resulted in the identification of 8,035 items from 46 boxes. You can browse the listing on Discovery. The records are not digitised but are available to order and view in our Reading Rooms.

Lists of enslaved people in the collection

Among the diverse array of uncatalogued and miscellaneous material are lists of enslaved people, held as ‘castle slaves’ in the British forts along the west coast of Africa. While the Company of Merchants were not permitted to engage in the Atlantic slave trade as a corporation, they continued to use enslaved people to work the forts across the West African coast from Senegambia to the Bight of Benin. These men, women and children were often called ‘Castle Slaves’, a distinct form of enslaved labour, where people received a wage and some limited rights but were still considered property of the company.

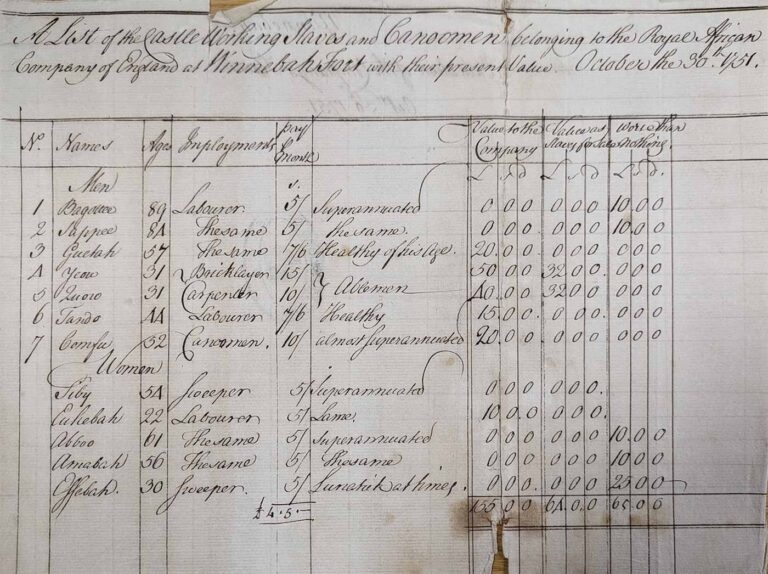

The pictured document, T 70/1517/3, is just one of the many lists of enslaved people in the Detached Papers. Dated 30 October 1751, it lists 12 people – seven men and five women – who worked at Winneba Fort (in what is now Ghana), giving their name, age, wage, employment and ‘value to the company’. The Winneba list is one of the shorter ones; one from Cape Coast Castle in the same year lists 132 enslaved people, 60 of whom were children.

However, on this small scrap of paper, we can learn a bit more about the existence of the people whose freedom was stolen from them in the name of profit and trade. Yeow and Quoro were 31-year-old labourers, a bricklayer and carpenter, respectively, described as ‘ablemen’. In contrast, labourers Bagottee and Sapee were described as ‘superannuated’, meaning they were unable to work due to old age and were subsequently costing the company money. They were 89 and 84 years old. The same was written of Siby, a 54-year-old female sweeper.

Effebah was also a sweeper. She was 30 years old and described as a ‘lunatic at times’. One can only imagine what the experience of Effebah and her enslaved kinfolk might have been, and we have to question why the behaviour she presented was interpreted as ‘lunacy’ by her captors. Did she try to resist? Was she defiant? Was this the manifestation of the trauma of her enslavement? Among the reams of receipts and account books, it is important we do not lose sight of the people like Effebah whose lives were at the centre of this trade and the importance of the fragmentary details we can recover of their existence.

Stories of resistance

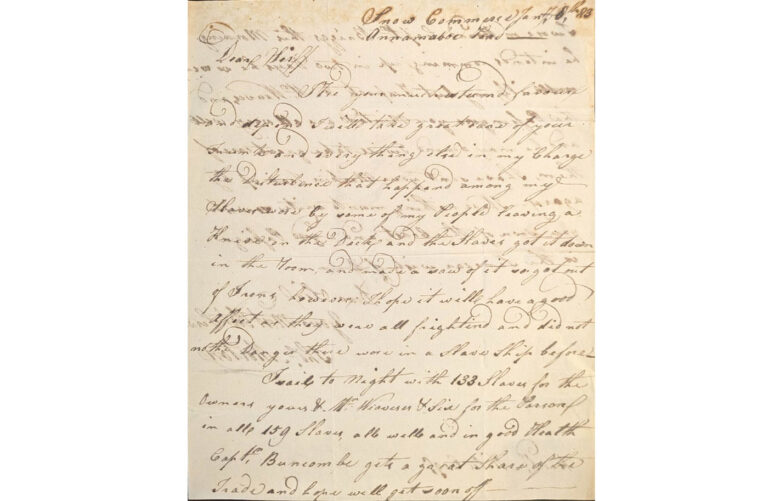

These lists are just one element of the Detached Papers. Letters make up the largest proportion of record type in the collection, offering unprecedented insight into the operations of the Company of Merchants.

One particularly powerful letter details the attempts of the enslaved Africans on the ship Commerce to resist their captors, stealing a knife from aboard the deck, and releasing themselves from their irons before then being coerced into submission. These perspectives are incredibly important for tracing histories of enslaved resistance and giving historical agency to those whose freedom was taken from them.

The men, women and children documented in the lists and similar documents in the Detached Papers are just a small proportion of the millions of Africans forcibly transported across the Atlantic to work on plantations in the Americas. The archival imprint of those whose legal freedom was stolen from them is so faint that even finding names buried in the heaps of bureaucratic paperwork is an important step in building a history of a people whose personal histories are rarely represented in the historic record.

You can find more records from the Detached Papers on Discovery or view other related records we hold in our transatlantic slavery collection gallery.

- William Pettigrew, Freedom’s Debt: The Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752 (UNC Press, 2013), p. 11. ↩︎

- Slave Voyages database: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade – Database (slavevoyages.org) (accessed 18/10/2024) ↩︎

Giving names to the many victims is a worthy effort. They were not just slaves. They were Father’s, mothers, sons and daughters that belonged to a family, tribe and kingdom.

Powerful and detailed yet some of the castle slaves were supported into old age. Did that happen to british miners, potters or mill workers. Doesn’t make it right but one also has to not look at Britain in isolation. Portugal, Belgium, and other Europeans were also in the trade, not discounting the African and Arab slave trade

The greater the detail level, the clearer our history becomes. The true horrors of colonialism and the slavers were kept out of the classroom for far too long. Times, as Dylan sang, are a-changing. And so they should.

Well-done, but long overdue .

Mental illness was believed to be triggered by certain phases of the cycle of the moon. Anyone who appeared to show symptoms of mental distress was described as “a lunatic.” It was in common usage and appears in British census records – along with other terminology that thankfully, wouldn’t be used today.

I had no idea that some slaves were retained by the Royal Africa Company for use within the three forts maintained by the British.