In 1940 Britain began to take an interest in using Crete as a military base, eventually establishing a garrison there. But in May 1941 German forces launched their airborne invasion of the island, seizing it in a close-run battle.

This blog will outline the British preparations for the occupation and defence of Crete, as well as the many relevant sources available at The National Archives.

Researching Crete in The National Archives

Many of the sources for Crete can be traced quickly by using a simple search in our catalogue, Discovery. A selection of records for 1940-1941 is shown here, though other search methods might be needed as well. There are military operational such as Army war diaries, RAF operations records books and Royal Navy ships’ logs. These records are listed by the identity of the unit or name of ship, so it is helpful to have some of this information before beginning the search. Our library can be useful too, and we have some books on the topic shown in our library catalogue.

The island and early British interest

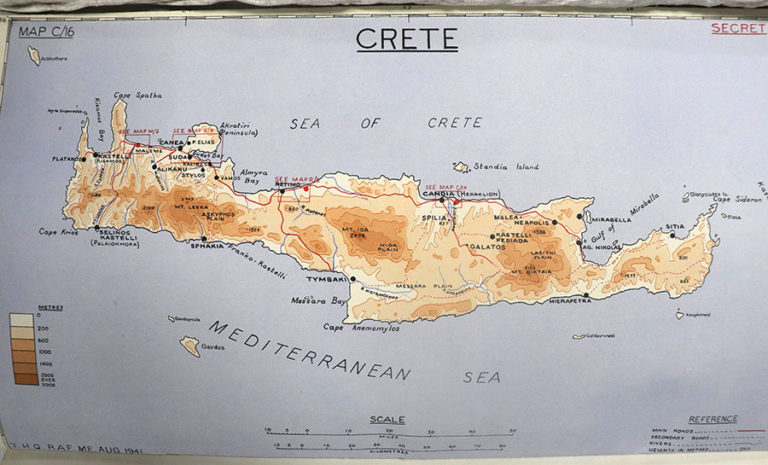

Crete measures about 260km in length and much of it is mountainous. The key towns and facilities were situated on the northern coastal plain, but the island was poorly developed in 1940, and this affected British planning for its defence. A military survey of Crete, compiled after the battle, outlines the infrastructure and resources on the island (WO 252/1201).

Crete was first discussed by the War Cabinet and Chiefs of Staff Committee before June 1940, in anticipation of war with Italy. The earliest mention of Crete in the War Cabinet Minutes was on 14 May 1940, when the seizure of the island was proposed, even though Greece was neutral at the time (CAB 65/7/17). In particular, Suda (or Souda) Bay was considered as a possible fuelling base for the Royal Navy (WO 201/3).

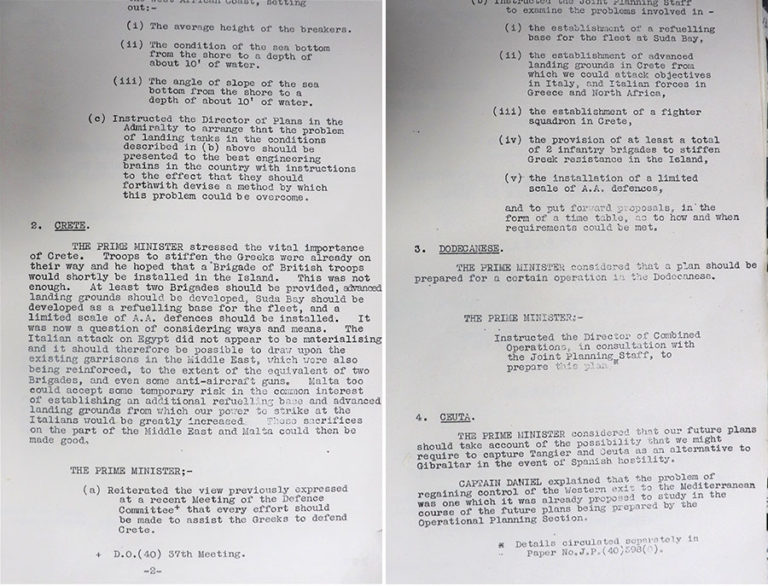

On 28 October 1940 Italy went to war with Greece, and Britain began to provide the Greeks with military aid. Some initial measures taken to defend Crete were discussed at a Joint Planning Committee meeting with the Prime Minister on 29 October.

Responsibility for Greece and Crete was assigned to the British Middle East Command, which had its headquarters in Egypt and was commanded by General Wavell. There were many other demands on Wavell’s attention and resources, stretching from Malta to Iraq, and this put a limit on British preparations for Crete.

Creforce and Crete as a base

The first significant British force to arrive was the 14 Infantry Brigade, which was sent in November 1940 and became the nucleus of Creforce, as the garrison was named. The war diary of the Creforce HQ (WO 169/1334A) includes a summary narrative of the arrival of the first troops on the island.

Crete had only meagre facilities in 1940 and British forces spent the next few months developing the island as a base. New airfields were constructed at Maleme and Retimo (or Rethymnon) in addition to the existing one at Heraklion. The airfields, especially Maleme, became key objectives during the battle. Work on the airfields is summarised in WO 106/3243 (note that Maleme was misspelled in this report).

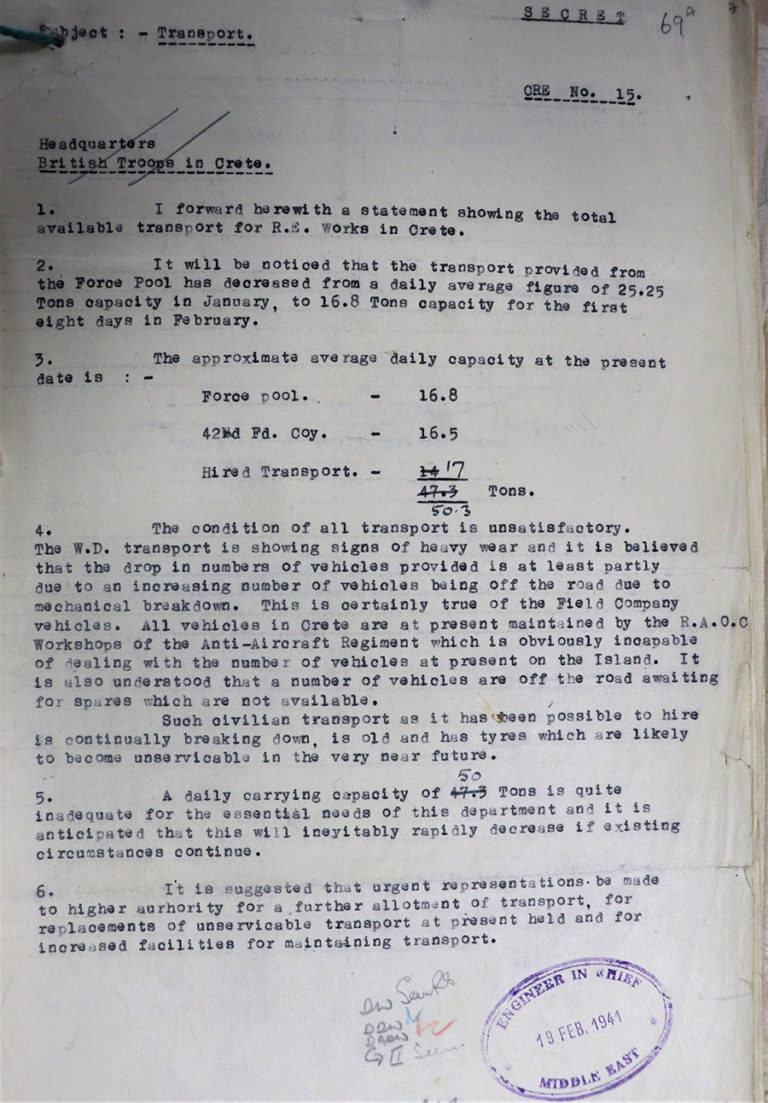

There were various other logistical difficulties facing the British forces in Crete. The island had only a single motor road, along the north coast, and the main ports at Suda Bay and Heraklion were quite small. Inadequate motor transport was another problem, with many vehicles off the road in need of spare parts and repairs.

Crete remained a low priority before April 1941, however, as British resources were needed elsewhere. Most of the Allied troops and equipment provided for Greece were sent to the mainland, where the Italian effort was concentrated, and Crete itself was left relatively undisturbed during this period. There was, however, an attack on Suda Bay by Italian motor boats, which crippled the heavy cruiser HMS York (ADM 223/685).

The growing threat to the island

The importance of Crete changed quickly in April 1941, when Germany launched an invasion of Greece, to support the faltering Italian campaign there and to oust the Allied forces from the mainland. The Allies were soon forced to evacuate, with some troops being disembarked on Crete to save time.

The Germans also planned an invasion of the island, known as ‘Operation Mercury’, and began assembling forces and creating bases for this purpose. This was confirmed in a directive issued by Hitler on 25 April.

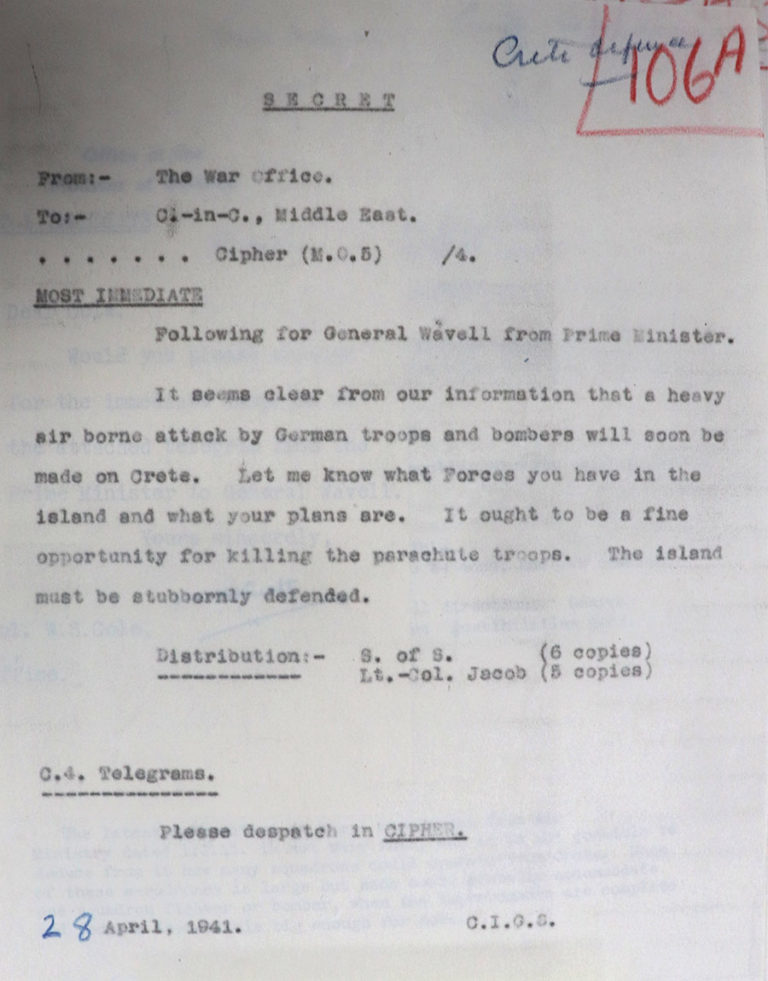

Crete was now a front-line Allied outpost, and Wavell was expected to hold it. The Prime Minister emphasised this policy in a signal stating that the island had to be ‘stubbornly defended’.

In the meantime, German aircraft began operating over Crete and Allied ships came under attack, making it more difficult to keep the island supplied. The cargo ship Araybank was sunk in Suda Bay, and there is a movement card for this vessel at BT 389/2/30.

Allied preparations for battle

Crete saw a large increase in the numbers of Allied personnel by late April, most being evacuees from the Greek mainland. Wavell visited on 30 April and General Freyberg, who had just arrived with his 2 New Zealand Division, was appointed commander of Creforce. He had more than 40,000 men available, including Australian, British and Greek troops as well as his own division, and a few tanks. However, many men had lost their equipment and become disorganised during the evacuation, and some were poorly trained. Inadequate communications was another handicap affecting the defenders, and the supply of telephones before the battle is mentioned in WO 201/101.

Above all, the lack of air support was a crucial weakness; only a handful of British aircraft were based on Crete but none remained by 20 May and the island was exposed to heavy air attack. Freyberg positioned most of his forces along the coast between Maleme and Heraklion to cover the airfields and harbours, though their mobility was quite limited. On the other hand, with the Enigma decrypts he had detailed warning of German plans. An example of an Enigma decrypt can be downloaded from DEFE 3/894.