This year, when you completed your 2021 census, you were participating in an ambitious, information-gathering exercise with a very long history. Since 1801, an official census has been taken every 10 years, with only a few exceptions. In this article we look at the history of the census in Britain and how it has changed over time.

What is the census?

The Office for National Statistics, responsible for taking the census in England and Wales, describes it as follows:

The census is a survey that takes place every 10 years. It gives us the most accurate estimate of all the people and household … asks questions about you, your household and your home … it builds a detailed snapshot of society. Information from the census helps the government and local authorities to plan and fund local services, such as education, doctors’ surgeries and roads.

Expert Professor Edward Higgs has outlined the four main features of a census:

- It must count individuals separately.

- It must cover everyone within a defined area.

- It must present a ‘snap-shot’ of a population (i.e. it is taken on a specific date to prevent double-counting).

- It should be part of a series, at defined intervals (e.g. every 10 years to be able to identify trends over time).

But let’s take a step back – what is the history of information-gathering on this scale in Britain and which of those events can be considered a census in its truest form?

Counting every cow

In 1086, William the Conqueror wanted to learn about the kingdom he had ruled since the Battle of Hastings 20 years earlier. He ordered a detailed survey that would tell him who owned land, how much their possessions were worth and, most importantly, how much tax he could charge them.

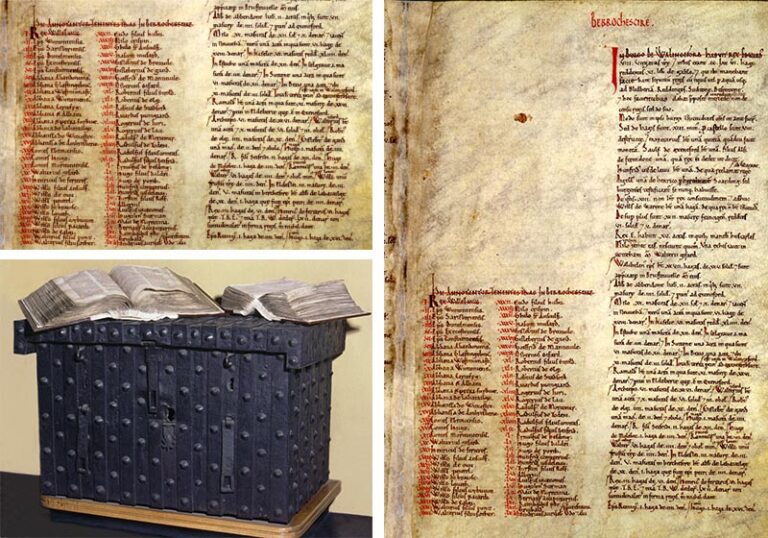

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes how ‘there was no single hide, nor a yard of land, nor indeed […] one ox nor one cow nor one pig which was there left out, and not put down in his record.’ This information was compiled into the ‘Domesday Book’.

This survey was very different to a modern census as it was concerned with land and taxation more than people. While it does not meet Professor Higgs’ definition, it is nevertheless a remarkable early example of a national information-gathering exercise.

Longshanks and his rolls

The next survey on this scale would not take place until the 13th century, when it was ordered by King Edward I. He was nicknamed ‘Edward Longshanks’ because he was unusually tall. Edward’s survey is known as the ‘Hundred Rolls’, named after the ‘hundreds’ (or administrative areas) that the country was divided into for this purpose of collecting information.

Like William the Conqueror, Edward used this exercise as a way of understanding which of his subjects had land and power. While this did not meet Professor Higgs’ definition of a census, it was a far more detailed survey than the Domesday Book because it gathered information about people from all classes. It was not only wealthy landowners who were listed, but also peasants and ‘serfs’ – people who were not free to leave the land where they worked. Sadly, many of the ‘rolls’ of information that were gathered in 1255 have been lost, but those that survive are stored at The National Archives.

Remarkably, more than 500 years would pass until the next survey was taken.

The origins of the modern census

In the 18th century, countries like Iceland (1703) and Sweden (1749) started to conduct their first official census. By the end of the century, thinkers and politicians in Britain were also asking important questions about the growing population in their own country.

In 1798, for instance, the economist Thomas Malthus published an influential essay suggesting that the country would eventually be unable to produce enough food to support its rapidly growing population. While his views were controversial (and ultimately disproven), they helped to highlight the fact that nobody knew exactly how many people were living in Britain.

These sorts of ideas, coupled with the context of a war with France, led to a gradually growing consensus that a population census was needed. The Census Act was therefore passed in 1800. It aimed to give the government a thorough understanding of the population, conveniently also telling them how many men could potentially be recruited for war.

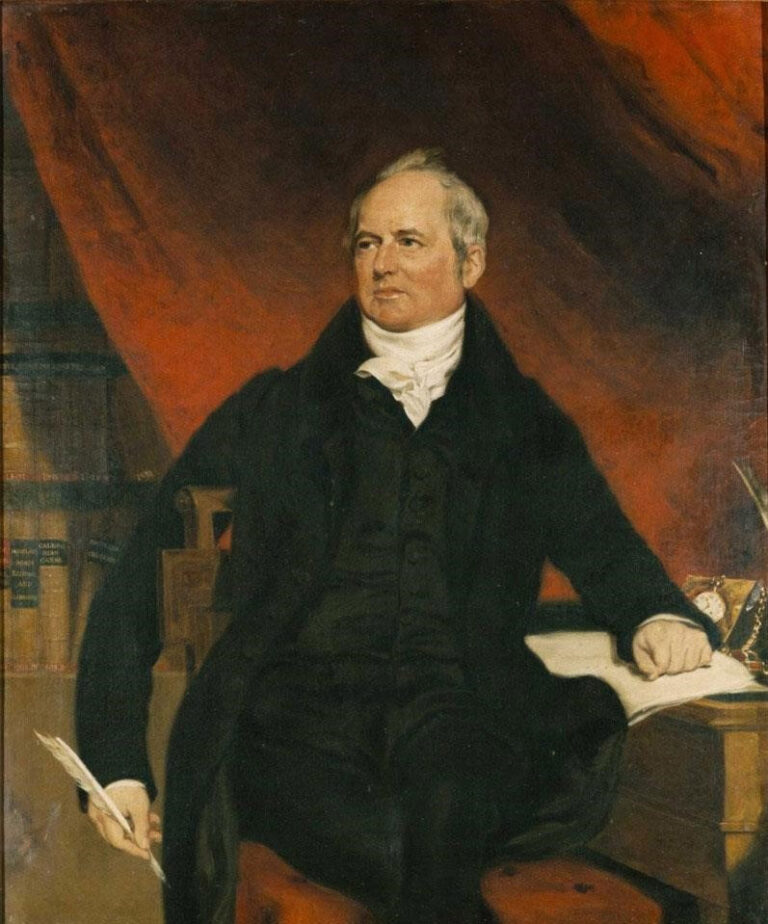

Rickman and the first censuses

John Rickman was a civil servant and statistician who oversaw the first census in Britain. He is widely known as the originator of the census, publishing various papers that preceded its introduction such as Thoughts on the Utility and Facility of a general enumeration of the people of the British Empire.

The four census overseen by Rickman, from 1801 through to 1841, did not fully meet Professor Higgs’ definition. This is because, instead of each household recording their own details individually, the information was collected in aggregate.

In fact, it was the district administrators, such as the overseers of the poor in England and Wales and the schoolmasters in Scotland, who were asked to provide the raw numbers of people and houses in their parishes. It was only later that each household provided their own data. Furthermore, there was also no specific date on which the census was to be taken, meaning that it did not provide a ‘snapshot’.

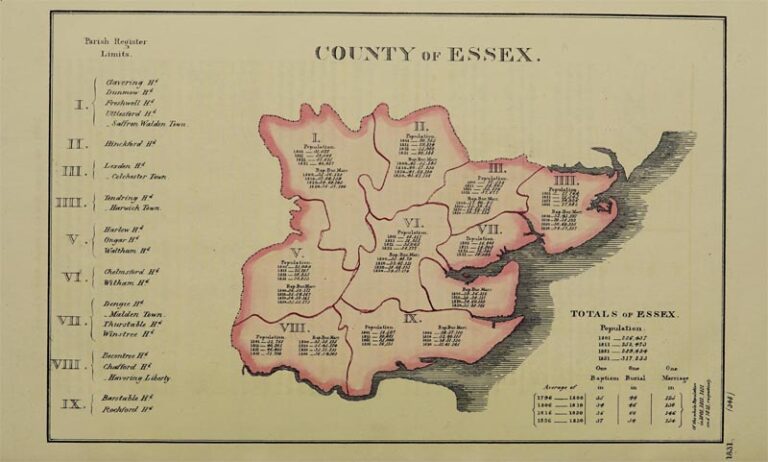

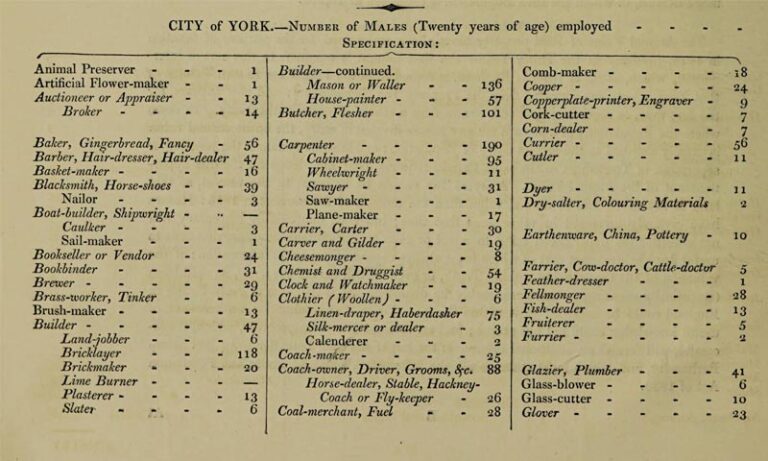

While the method of information collection did not change during this period, the questions that the census asked did evolve. Each year a little more data was captured. In 1821 the census first started to record people’s ages and in 1831 more detailed information was captured about the different industries in which people worked.

The enumerator calls

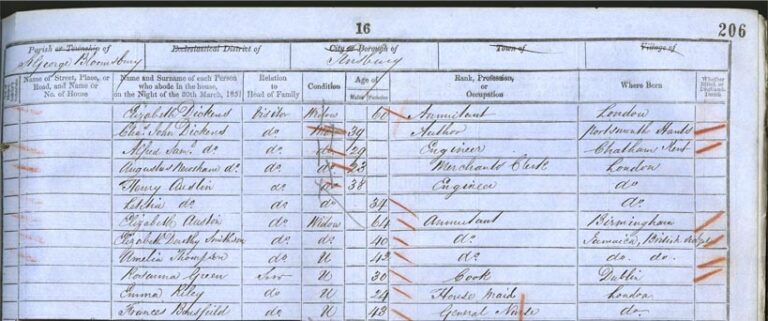

For the first time in 1841, responsibility for recording information was delegated to households. Each home was delivered a form that they had to complete by recording the details of every inhabitant. These forms were then returned to an official called an ‘enumerator’ who came to collect them.

If a family was unable to read or write, the enumerator could help them to fill in the form, but people also asked for help from friends or neighbours – sometimes in return for payment. Once the returns were all gathered up, the information on the forms was copied by hand into books. These are the records that survive today.

After Rickman died in 1840, his work fell to Thomas Henry Lister, who had been Registrar General since 1836. Lister really thought comprehensively about how the first census that householders had to complete themselves would take place. The extent of the detail he considered came down to the pencils that he mandated all 35,000 enumerators were to carry.

There was another change to the census in 1841, as individuals were asked for the first time where they had been born and not just where they currently lived. This indicates the Government’s acknowledgment that people were becoming increasingly mobile, demonstrating that they wanted to get a sense of how the population was changing in different parts of the country.

From counting to more informed analysis

In Victorian Britain, a formidable duo worked on the census for nearly 40 years. They were Registrar General George Graham and Dr William Farr, the Superintendent of Statistics.

George Graham took over the General Records Office (GRO) in 1842, ultimately overseeing the censuses of 1851, 1861 and 1871. He worked closely with his colleague William Farr who was a Fellow (and, for a time, President) of the Royal Statistical Society. Farr’s expertise in this area made him particularly effective at organising how the information gathered by the GRO was collected. He also designed the statistical tables used to present data. Having qualified as an epidemiologist, Farr was especially interested in how the census (and, later, Birth, Marriage and Death data) could improve public health.

Farr was good friends with Florence Nightingale – the founder of modern nursing. She had taken care of wounded soldiers during the Crimean War and was also the first female Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. When Nightingale returned to London, she worked with Farr to calculate the shocking mortality rate of military men. Farr described their work together as ‘light shining on a dark place’.

Throughout its history, the census has revealed the pressing issues of its time: from mortality and poverty in the later 19th century to growing concerns about the falling birth rate and declining public health in the early 20th century. The latter issues prompted the government to include questions about fertility in the 1911 census, asking married women to state how many children they had, counting both those that survived and those who had died.

New technology for the census

In 1911 there was an important change to the census: for the first time, the information it recorded was processed by machines. After the data had been collected, it was stored on a complex system of cards with holes punched in them. These were then fed into machines that collated the information.

For the first time ‘household schedules’ – the individual forms filled out by every house – were kept. This means that many researchers can see their ancestor’s handwriting rather than the enumerator’s transcription.

A wartime alternative

Between 1911 and the next census in 1921, the First World War had changed the face of the population. An estimated 886,000 British people had been killed in the conflict and the census took this into account. For instance, a question was added about orphanhood, reflecting the fact that many children had been left without parents due to hostilities.

The Second World War meant that plans for the 1941 census were scrapped. However, records do survive for a different information-gathering exercise that was carried out 29 September 1939. The 1939 Register cannot be considered a true census, but it does provide a snapshot of the civilian population just after the outbreak of the Second World War. You can find out more about the 1939 Register here.

In December 1942, while Britain was at war, the English and Welsh returns for the last full census of 1931 were destroyed. This was not due to enemy action, but a fire that broke out at the office where the documents were held. The Scottish records were luckily not affected, but the loss of so much information meant that the 1939 Register records became even more important, as there was no further census until 1951.

Computing the census

Computers were used to process census data for the first time in 1961. This was an important development, as it allowed experts to examine and interpret the information in more advanced ways.

Breaking with tradition, the government decided to introduce another census in 1966 – only five years after the last, instead of the traditional 10 years. Society was changing so rapidly that politicians felt they needed a better understanding of these shifts to form new policies. This only surveyed a sample of the population, however, so it should not be considered a true census. Over the next several decades, the questions asked by the census continued to expand and evolve. In 1991, for example, people were first asked about their ethnicity.

The new millennium

The census of 2001 asked people which religion they practised. This was the first time this question had been asked outside of Ireland since 1851. The question was optional, so people were not obliged to share this personal information.

In 2011 there was an even bigger change, as it became possible to complete the census online for the first time. About 16% of people decided to respond in this way. In 2021 even more people are expected to have completed their census online, with no paper forms being sent out, unless requested. Another key moment in the long story of our national census.

Dr Anna Maria Barry is a writer, historian and curator. She works on 19th-century culture.

Professor Edward Higgs used to work in the Public Record Office for those of us who worked there at the time. It was not the General Records Office but the General Register Office. The introduction of computers for the 1961 Census lead to justifiable fears about use of the information for ‘Big Brother’ and this fear covered any computer information, which still prevail. In fact the census records for 1901 were used by the Ministry of Pensions to calculate age of claimants despite the undertaking on the forms that they would not do so. Scotland’s Census has always been different, not least of when it was released, sometimes decades before the one for England and Wales. Scotland’s Census for 1931 was not affected by the fire during the Second World War because it was held in Edinburgh. I am surprised not to see a mention of the 1976 mid-term Census planned by Barbara Castle (Secretary of State for Social Services and the Minister responsible for the census) but which did not take place because it would have to be financed through her own department’s budgets, principally the NHS and social security.