At 22:00 on the evening of 7 April 1945, an Austrian Jew named Rolf Klink, who had recently arrived at Bergen-Belsen transit camp from Sachsenhausen concentration camp together with a group of other inmates, was ordered by an SS camp guard, Rapportführer Wilhelm Emmerich, to fetch a sick prisoner from the hospital at Block 17.

Emmerich then went away, and a more junior Unterscharführer took his place. Shortly after, a medical orderly brought the prisoner from the block and the Unterscharführer instructed Klink to take down the prisoner’s name and date of birth. Klink asked for these details, and the prisoner feebly took his hand to support himself, whispering his name, followed slowly by his date, month and year of birth. As the Unterscharführer advanced a few paces towards the door of the block, a gesture that it was time for them to leave, the prisoner turned and spoke to Klink these last words: ‘I know you love England’, he told his friend. ‘When you get there, tell them the truth” (WO 309/33)[ref]Sworn affidavit of Rolf Klink concerning Keith Mayer, taken by Major H H Cochrane at Bergen-Belsen, 7 May 1945, Catalogue ref: TNA WO 309/33.[/ref].

This was the last time Able Seaman Keith Mayor was seen alive. He was 22 years old.

75 years ago, on 17 September 1945, the Bergen-Belsen Trial commenced at Lüneburg, Germany. This would be the first of the post-war war crimes trials to occur in Europe after the close of the Second World War. The defendants would be 45 former SS men, women and kapos (prisoner guards) from the Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz concentration camps, including Josef Kramer, who had been camp commandant at Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz.

The interrogation reports and sworn affidavits in the case file for Rapportführer Emmerich and Hauptscharführer Balz, which was compiled for the trial by the BAOR (British Army of the Rhine) War Crimes Group, Judge Advocate General’s Office, and located in the WO 309 series, provides evidence that a Royal Navy sailor, Keith Mayor, whose name appeared at the top of the indictment, was murdered by a shot to the head by two SS camp guards just one week before the liberation of Bergen-Belsen by British forces.

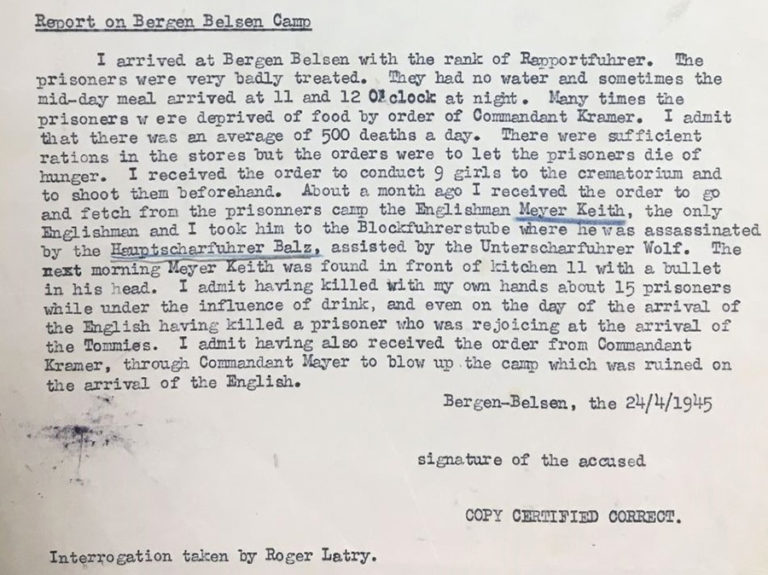

Emmerich’s interrogation report contains a confession concerning his part in the murder of Mayor, and of the terrible conditions at Bergen-Belsen camp to which he had borne witness since his arrival in late February 1945. Having previously served as a camp guard at Auschwitz, Emmerich’s statement also included details of crimes committed at that facility before detailing events at Bergen-Belsen, including forced starvation of inmates by order of camp commandant Kramer, resulting in the deaths of over 500 prisoners per day. Emmerich, himself, admitted to directly murdering, or participating in the murder of roughly 25 prisoners; nine girls whom he was ordered to shoot and dispose of by crematorium, 15 inmates whom he had randomly killed while drunk and one whom he had killed simply for rejoicing at the arrival of the British on the day of the liberation.

When it came to Mayor’s murder, however, Emmerich stated that he had only been ordered to fetch ‘the Englishman, Meyer Keith’, the only British inmate in the camp. Emmerich, according to his confession, had merely escorted him as far as the Blockführerstube where he was ‘assassinated by the Hauptscharführer Balz, assisted by Unterscharführer Wolf’. The next morning, Mayor was found lying in front of Kitchen 11 with a bullet in his head (WO 309/33)[ref]Report on the interrogation of Emmerich Wilhelm S.S., since 1938 in Auschwitz Concentration Camp and since 26/2/1945 in Bergen-Belsen Camp as Rapportführer, 24 April 1945, Catalogue ref: TNA WO 309/33.[/ref].

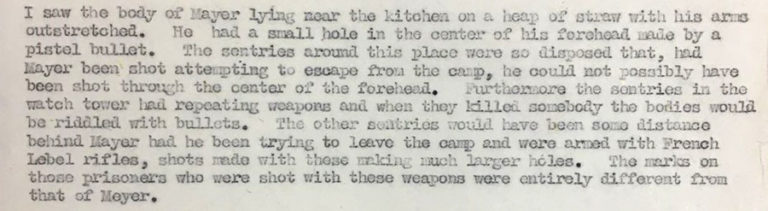

Mayor would be murdered in a manner that was a signature of the SS Totenkopfverbände (Concentration Camp Service), as another inmate, Frenchman Max Markowicz, attested in his affidavit. Markowicz had the grisly task of drawing up lists of prisoners who died at the camp, and he had frequently seen Mayor prior to his death. Having been shown Rolf Klink’s affidavit, he confirmed the identity of the unnamed Unterscharführer who had brought Mayor from Block 17 to his place of execution as that of Joachim Wolf.

Due to the nature of his duties at Belsen, Markowicz was intimately familiar with the various causes of death of each prisoner, and was able to identify the calibre of bullet used in the killing of inmates from the gunshot wounds on their bodies. This gruesome knowledge made him something of an expert witness when it came to determining whether or not Mayor had been shot while trying to escape (WO 309/33)[ref]Exhibit ‘A’ (38); Sworn affidavit of Max Markowicz concerning Keith Mayer, taken by Major H H Cochrane at Bergen-Belsen, 4 May 1945, Catalogue ref: TNA WO 309/33.[/ref].

Markowicz further stated that, in his experience, when prisoners were to be shot without an execution, a number of formalities were undertaken. Normally, he would be detailed to take the name and number of the person in question, and make a sketch of where they were found, so that they ‘could be shown to have been shot escaping’. In Mayor’s case, no such procedure was carried out. Markowicz concluded that it was likely that the order to kill Mayor had come from the camp’s political department, run by Obersturmführer Friedrich and Unterscharführer Pott. This department, which took orders directly from Berlin, had authority to kill individual inmates and was very likely to have acted upon a direct order to execute Mayor (WO 309/33)[ref]Ibid[/ref].

So why was a British sailor, a fully-fledged member of Britain’s armed forces, executed by SS guards at a concentration camp in Germany, possibly on the orders of their superiors in Berlin, one week before his compatriots had an opportunity to rescue him?

A far more pressing question is why any member of the Royal Navy would end their days in a concentration camp, rather than a camp for prisoners of war, and be subjected to appalling degradations and murder, instead of the rights normally afforded to Allied POWs under the Geneva Convention. To both questions, an answer can be found in German wartime policy towards British commandos.

Able Seaman Mayor was no ordinary sailor. In 1942, he volunteered to join the Royal Naval Commandos, a new formation created by the Royal Navy to conduct special operations. Mayor became a member of No. 14 (Arctic) Commando, a special 60-man force organised to conduct sabotage missions against enemy targets in German-occupied Norway. In April 1943, Mayor was selected for a seven-man team detailed to carry out ‘Operation Checkmate’, a raid on shipping at Haugesund, and the last of 12 commando raids staged along the Norwegian coast during the Second World War. Four of the commandos were issued with two canoes with which to carry out their mission. Lieutenant Godwin and Able Seaman Burgess made one crew while the other included Able Seamen Mayor and West. Under the cover of darkness, they used a small local fishing boat to move within striking distance of their targets, launched the canoes to get in closer and then planted their Limpet mines on the hulls of the target ships. During the operation they managed to sink one German vessel, the minesweeper, M. 5207. The party were later captured on 14 May 1943, after an extensive search by German occupation forces[ref]T R Moreman, British Commandos 1940–46 (Oxford: Osprey, 2006), p. 24.[/ref].

All members of Operation Checkmate should have been treated as prisoners of war as they had been captured in uniform. However, in 1942, Adolf Hitler had issued the Commando Order, stipulating that all captured commandos, no matter if they were in uniform or not, were to be executed shortly after interrogation. Instead, these commandos would be turned over to the Sicherheitsdeinst for interrogation, before being sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Here they endured horrific treatment, such as being forced to break in German Army boots by marching 30 miles a day over cobblestones. Later, five members of the commando team were executed, together with 132 other Allied POWs, on 2 February 1945. Shortly thereafter, Mayor and Alfred Roe, now the only surviving members, were transferred to Belsen. When Roe died of typhus soon after arrival, Mayor became the last of the Checkmate commandos[ref]Philip D Chinnery, Hitler’s Atrocities Against Allied POWs: War Crimes of the Third Reich (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2018), p. 265.[/ref].

Rolf Klink, the last friend of Mayor to see him alive, befriended him upon his arrival at Sachsenhausen. He remembered the arrival of the British sailors, dressed in their uniforms, and recalled watching them being forced-marched in the months that followed. Klink, who brought these sailors food rations, also spoke English and struck up a friendship with Mayor.

According to Klink’s affidavit, Mayor and Roe were forgotten at Sachsenhausen when their five comrades were loaded on to transports and taken away. Klink would accompany Mayor and Roe when they were transferred to Belsen along with thousands of other Sachsenhausen prisoners. Once they reached Belsen, Klink had Mayor registered as Dutch so that the camp authorities would take less notice of him.

Unfortunately, Mayor quickly fell ill with typhus symptoms and was eventually transferred to the hospital at Block 17. Soon Rapportführer Emmerich came looking for Mayor, having been detailed to locate two prisoners who were designated to be transported out of the camp. One of the identity numbers given to Emmerich was that of Mayor; the other may have been Roe’s. When Emmerich learned of Mayor’s illness, this sealed the young sailor’s fate[ref]Sworn affidavit of Rolf Klink concerning Keith Mayer, 7 May 1945, Catalogue ref: TNA WO 309/33.[/ref].

In September 1945, British military authorities would initiate the Bergen-Belsen Trials for wartime atrocities. Forty-five defendants, including the camp commandant, Kramer, would be tried in a duration of two months. For legal reasons, however, the British needed a domestic interest in order to prosecute the defendants – there needed to be at least one British victim of the Bergen-Belsen atrocities for the trial to have any legal grounds. When prosecutors learned of Mayor’s death, and were able to produce proof that the death had been an unlawful killing using the testimony in Max Markowicz’s affidavit, the requirements of the Royal Charter were, thereby, satisfied. When the charges were read out at the trial, Count One featured the name of ‘Keith Meyer (a British national)’ at the head of a list of 17 named victims from various countries. Thus, Mayor’s murder had provided the basis in British law for the Bergen-Belsen Trials to take place – without it, they might never have occurred[ref]Larissa Allwork & Rachel Pistol (eds.) The Jews, the Holocaust, and the Public: The Legacies of David Cesarani (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), p. 215.[/ref].

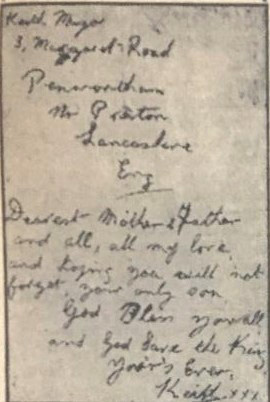

Yet, for all the importance of his otherwise meaningless death in the bringing to justice of dozens of Nazi war criminals, very little is known about the Preston-born sailor except that he was his parents’ only son. What little we can understand of Mayor’s own inner feelings are conveyed in a tiny but moving letter that he scribbled to his family – a little fragment of love which survived the horrors of Bergen-Belsen:

‘Dearest Mother and Father and all,

All my love, and hoping you will not forget your only son.God bless you all, and God save the King.

Yours ever,

Keith’ (WO 309/33). [ref]Letter from Able Seaman Keith Mayor to his parents at Margaret Road, Preston, reproduced by Sunday Express, 17 June 1945, Catalogue ref: TNA WO 309/33.[/ref]

I see Keith Mayor was from Preston, Lancs. so I’m thinking could my dad

have know him or members of his family. My dad grew up with six brothers

& a sister in Preston. He had friends & relatives from Preston who served in the armed forces during WWII.

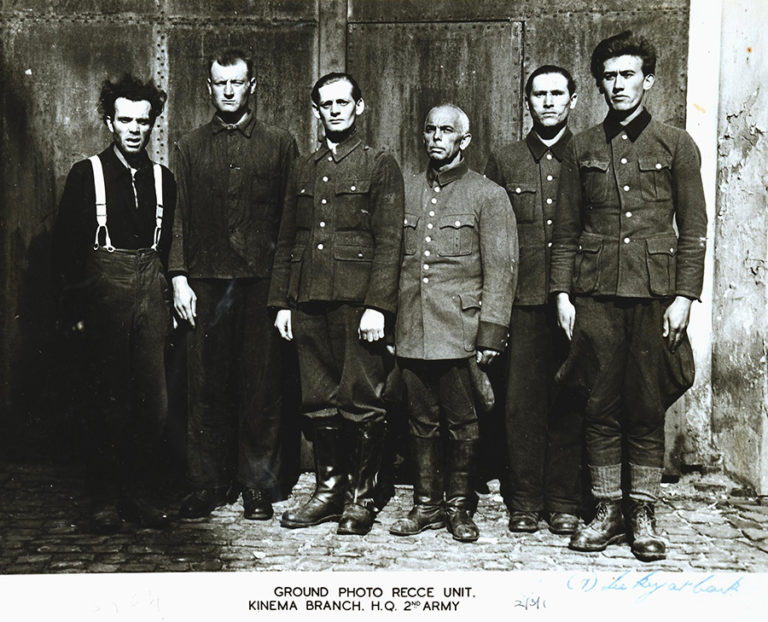

This is not an image of Unterscharführer Joachim Wolf (third man standing from left) Catalogue ref: WO 235/19 Part 2 (4). Check the archives this is inaccurate.

He was from Penwortham A village near Preston. My mother is now 90 and remembers his family well. His sister was a close friend.

The case was constantly in the local and national papers and the stress destroyed his parents health. My mother said that the hair of one of them (I can’t remember which) turned white overnight with the strain of keep reading about their son and what he had endured.