‘Deficiency of housing accommodation is one of the most prolific causes of industrial unrest.’ CAB 24/42/94

This is the first of two blogs relating the story of the birth of council housing in Britain. It is a subject that has inspired a new Outreach project, ‘This is our Home’, which will work with adults at SHARE. Although the community aspect of the project has been postponed for the time being, when the project eventually goes ahead participants will visit an estate built as a consequence of the 1919 Housing Act. They will then create artistic outputs inspired by records held at The National Archives and Wandsworth Heritage Service.

The project has engaged local people as well as archivists, and has inspired me to research the path towards the Act that enabled new council housing at a national and local level. In my second blog I will describe how the students used the resources here at The National Archives and Wandsworth Heritage Service, and discuss learning outcomes. But first I will explain how the Act came to pass.

The 1919 Housing Acts

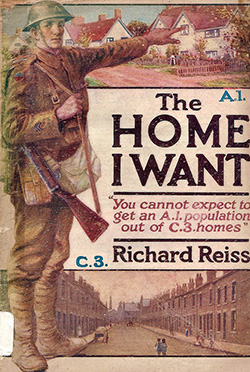

In February 1918 George Barnes MP, member of the Wartime Coalition, wrote a Memorandum to the War Cabinet (CAB 24/42/94) quoted above. The Great War had accelerated the view that housing policy could no longer be left to the vagaries of the market. The question facing politicians at the conclusion of war was whether it was legitimate for government (both central and local) to intervene in the housing market. At Armistice, the pressure for intervention – due to a national housing shortage, increasing threats of social unrest and rising costs – was overwhelming. Was Prime Minister Lloyd George forced to call for ‘homes fit for heroes’?

The context of the housing crisis at Armistice can best be explained by the political and social climate at the end of the war. Professional groups – trade unions, architects, social reformers, even some MPs – were calling for a different kind of society.

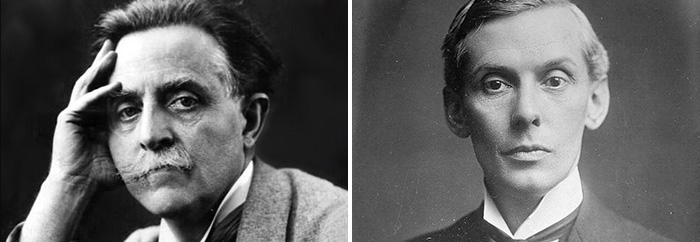

Earlier, a few benevolent industrialists, like Lever at Port Sunlight and Cadbury at Bourneville‚ had created ‘model villages’ or ‘garden suburbs’ for their workers. Ebenezer Howard had created a ‘garden city’ at Letchworth (1903) with green public spaces and social amenities normally only experienced by the prosperous middle classes. Similarly, the architect Raymond Unwin had designed houses and green spaces for the ‘garden suburb’ at Hampstead (1906). Why could such houses and estates not be built for the working class?

Politicians were deeply worried that revolution and social unrest, already evident in Russia and Germany, would spread to Britain. Industrial unrest and the boycotting of peace celebrations were evident across the UK in 1919. In Cabinet, Lloyd George believed Britain would hold out (against Bolshevism) ‘only if the people were given a sense of confidence if made to believe things were being done for them’ (CAB 23/9 (539)).

In this atmosphere Christopher Addison, head of the Local Government Board, presented a housing bill to Cabinet. Addison recommended that local authorities submit plans for housing schemes and limit the local authority’s financial responsibility to the product of a penny rate per annum: the residual cost to be borne by the Exchequer. The work would be supervised by the new Ministry of Health through a Housing Commissioner in each of 11 regions. The bill became law in July 1919. In December 1919 an additional Powers Act helped private builders gain a lump-sum subsidy to build.

The Housing & Town Planning Act 1919 allowed local authorities, like the London County Council, to clear slum dwellings and compulsorily purchase land, while also submitting new estate plans embracing ideas from the ‘garden suburb’ movement. Housing standards were to be improved, with the inclusion of an indoor bathroom and WC as well as front and rear gardens.

The Dover House Estate, Roehampton

One such estate built was the Dover House Estate in Roehampton. Land was purchased in July 1919 and approximately 1,250 houses would eventually be built. As a consequence of the increase in both materials and labour costs, only 17 houses had been completed by May 1921 and the final houses were not completed until 1927. The cost of houses increased enormously between 1918 and 1921 from an average £500 to £1,150 per house – labour shortages and increased prices for materials being the reasons for this increase.

Nevertheless, the Dover House Estate set a standard. Carefully tended, square-cut hedges match the square-cut red brick, red-roofed houses. Many houses are set back in ‘neo-Georgian’ curved street patterns. There is also attention to detailing in porches, doors and windows and variety in a range of rooflines – gable and hipped ends, dormer windows and mansard roofs. Instead of a pre-war density of 27 houses to the acre, the houses at Roehampton were built at 15.8 per acre on a small estate of 76 acres.

‘This is our Home’ will use archival documents to inspire art works by SHARE students that will subsequently go on display to the public. Further details of this will be released at a later date.

Very interesting blog. So important to know about how our living environments evolved and the history hidden in our streets. So valuable to know too the processes and influences which helped create them. Thank you for this informative blog

As a local resident for 20 years now I find this blog very interesting and am looking forward to the next one. Many thanks for keeping local history alive! Helena

How wonderful to have local history pointed out and explained in this blog. Great too to hear about the outreach programme. Thank you.

I have just tumbled upon this archive site by accident and what a wonderful treat. I think the National Archives at Kew are one of our unsung national treasures and so it is wonderful to have stories pulled from their depths and shared publicly online like this. I know historians are already indebted to the National Archive for the pages of their books. And this is such a timely post/blog. Interesting in and of itself but in the current Covid hell, it is rather uplifting to think that our nation responds to calamity with positive social action for the greater good. So thank you so much to whichever archivist designed to share the story with us.

What a lovely piece, capturing the history of Putney, where I was born and lived for 30 years. In a city with such a rich and varied history, details like this are so easily lost. Thank you for resurrecting them!

Learning things I never knew about my locally area … and about social housing. So looking forward to the next instalment !! My 13 year old also found this interesting which is a testament on how it captured all ages !

Very interesting overview into the thinking post First World War. Considering the romantic thoughts in 1919 that forms the basis of the social housing project versus 100 years on where we have a social housing crisis and run-down London council houses, it seems very relevant to dig out this piece of history. Thank you.

Such interesting reading especially for a retired Planning Solicitor dealing with local authority slum clearance schemes in the early 60’s. Was wholesale demolition the correct answer with paltry sums paid out in compensation merely for site value ? In retrospect I think some unfit housing could have been saved by improving and/or amalgamating some houses thus not only retaining some of the vital communities and their spirits which were decimated but also avoiding the later social problems stemming from the new sprawling Council estates and high rise flats built on the cleared sites. The sale of Council houses whilst fine in theory was flawed by the Government of the day not allowing sale proceeds to be ploughed back into social housing. As a Yorkshire man I must add to the examples of model villages 1) that of Saltaire near Bradford now a World Heritage site built by the philanthropist Sir Titus Salt and 2) Copley and Ackroyden near Halifax, villages promoted by Col Edward Ackroyd

Very interesting article. I stumbled across it when researching self build schemes. My father believed he was a pioneer of the concept when he set up the first one in Flixton, Manchester in the early 1950’s. He arranged a loan with the local council and bought a plot of land. He then brought together a team of skilled workers who over several years built a small estate of houses. Each member of the team got a house, including my father. Balmoral Avenue still exists. I think he might be have been right.

Really enjoyed this piece of work. So important to document our local history. A painstaking job so well done!

Have just discovered this really interesting article. Amazing to learn about local history and about social housing. Many thanks and I’m looking forward to reading future articles.

I found this an informative and easy to understand account about council housing immediately after the First World War. It will be very useful to those teaching and studying the social history of inter-war Britain and in particular the question of whether post-war Britain failed to become a land fit for heroes.