In the first of our #Readeption550 series of blogs, we saw how Edward IV, faced with the return of the Readeption rebels – his brother George, Duke of Clarence, and Warwick ‘the Kingmaker’ – was forced to flee England in October 1470 with barely the clothes on his own back. In this blog I take a look at some of those left behind in England during Edward’s exile in Burgundy, and the events surrounding the birth of his first-born son on 2 November 1470.

At the time of Edward’s flight from Bishop’s Lynn to Burgundy, the queen, Elizabeth Woodville, was heavily pregnant with the child who would later become Edward V, probably best known as one of the ‘Princes in the Tower’. Before London had succumbed to the invading forces, Woodville, alongside her mother, Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, and her young daughters fled the Tower of London and immediately sought sanctuary at Westminster Abbey, where they would be safe from the invading force[ref]Woodville was not the only one to seek safety in sanctuary. Edward’s leading officials, including the Chancellor Bishop Stillington, and Keeper of the Privy Seal, Bishop Rotheram, would also seek refuge at the historic sanctuary site at St Martin le Grand, while many of those in the Tower of London garrison would join their fellow Yorkists when the Tower surrendered on 3 October.[/ref].

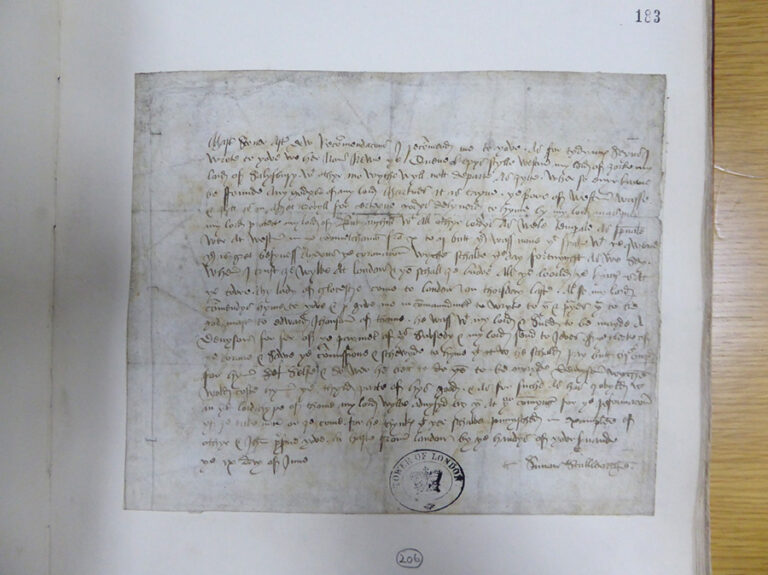

While the sanctuary at Westminster may not have been the location in which Woodville would have chosen to give birth (the chamber set aside for her confinement at the Tower was instead given over to the restored king, Henry VI), the queen and her family were allowed to remain safe and undisturbed. A proclamation by Henry’s council was clear in forbidding the troubling of those in sanctuary for any cause, while Woodville and ‘her household’ were allowed a supply of ‘half a beef and two muttons’ each week by a London butcher, William Gowld, for which he was rewarded by Edward IV on his return. Gowld would also provide 100 oxen to a meadow by the Tower in the aftermath of the battle of Tewkesbury, although on this occasion half of his animals were stolen by rebels.

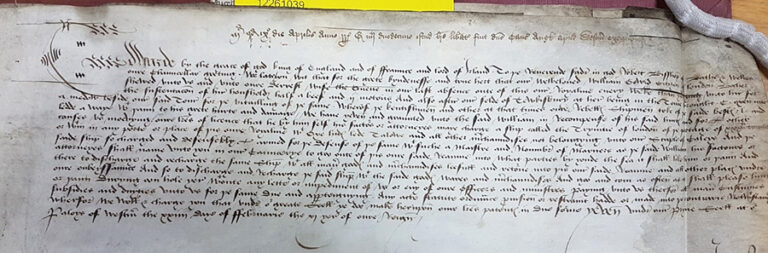

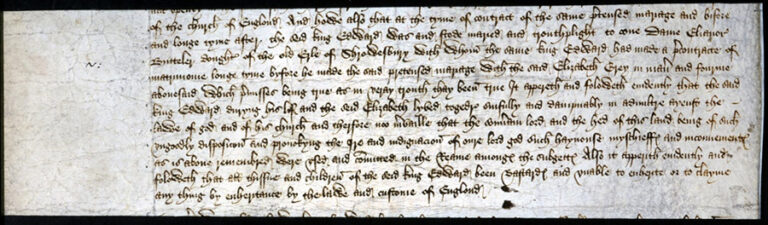

![Handwritten page documenting the apope ‘for her attendance ... about Elizabeth, late calling her[self] Queen’ during her confinement.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/02143348/edward_v_22-768x305.jpg)

As well as food, Woodville also received a measure of support from the restored Henry VI and his council during her confinement, as Elizabeth, Lady Scrope, was granted £10 out of the Exchequer on 30 October 1470 for her attendance on Woodville during her confinement.

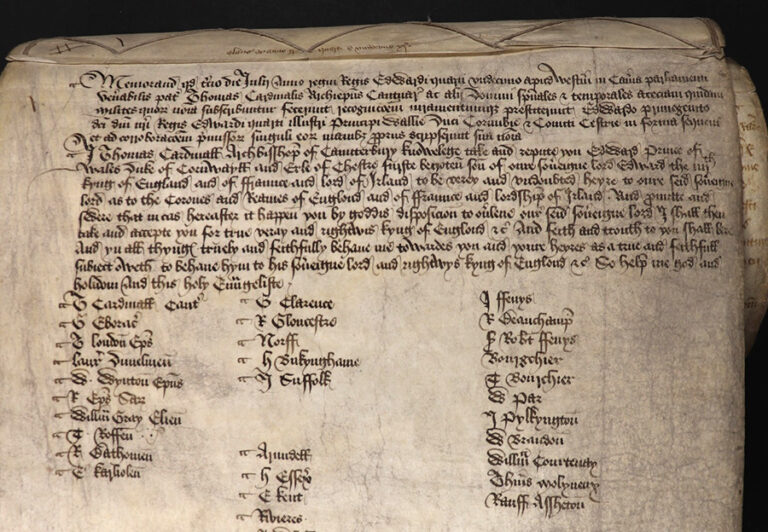

Edward was born on 2 November 1470. While there are no records relating to the birth itself, we can establish the date from a later grant of 10 December 1472, when the young prince received from his father the issues of the duchy of Cornwall for the period Michaelmas 1470 until 2 November then following ‘on which day he was born’.

‘The kyng comfortid the quene and other ladyes eke;

His swete babis full tendurly he did kys;

The yonge prince he behelde and in his armys did bere’

Political Poems and Songs, II, 274. From Cora Scofield, The Life and Reign of Edward IV (London, 1923), I, 577

The queen and her new-born son would remain in sanctuary for another five months before the triumphant return of Edward IV from exile. After receiving the surrender of London on 11 April 1471, and meeting the now re-captured Henry VI, Edward went to meet his wife and children at Westminster (pausing first for a brief ceremony where the Archbishop of Canterbury placed the crown back on his head), who had left sanctuary to return to royal lodgings.

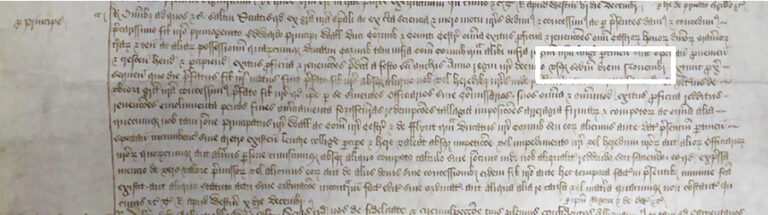

With Edward IV’s crushing victories at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury, and the death of Henry VI, Edward had secured his kingdom, and he now had a son and heir in Edward, Prince of Wales. On 3 July 1471, the peers and prelates of the realm gathered at Westminster and swore an oath to recognise the prince as Edward’s heir. While a son and heir was no guarantee of future peace (as we shall see) the prince’s birth provided hope for a country once again turned upside down by civil war, bitter rivalries, personal violence, legal feuds and general distraction among the ruling elites, offering the possibility of a peaceful transition of power after his father’s death.

The relative peace would, however, be short-lived. Much of Edward’s early life, education and training were overseen by a corporation of courtiers and members of the royal family, focusing in particular on the principality of Wales and the counties of Chester and Flint where he (or perhaps more importantly his council) was given relatively free reign for Edward to learn his craft as the future king of England. The secondary power base his council built up in Ludlow (strongly influenced by his mother, the Queen, and her Grey-Woodville family) would prove to be a major factor in the young king’s downfall[ref]This is explored in considerably more detail in an upcoming publication by my colleague Sean Cunningham: S. Cunningham, ‘A Yorkist Legacy for the Tudor Prince of Wales on the Welsh Marches: Affinity-Building, Regional Government and National Politics, 1471-1502’, in Fifteenth Century XVIII. Rulers, Regions and Retinues: Essays presented to Tony Pollard, edited by Linda Clark and Peter Fleming (Boydell, Woodbridge, 2020). pp. 119-30.[/ref].

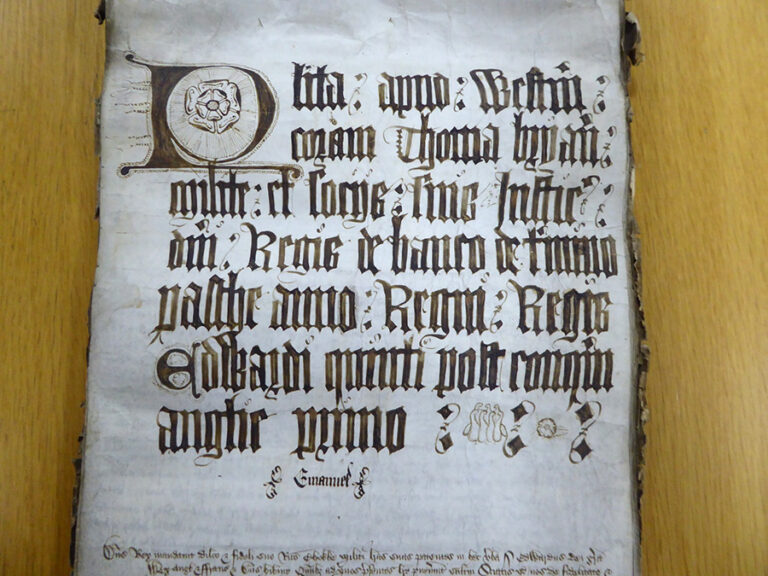

Edward IV died on 9 April 1483 at the age of just 40, less than 12 years after first meeting his son and heir. His son, now Edward V, succeeded to the throne, and we hold a small number of records from his brief reign (as officials were re-appointed, and the business of government and the law continued) but Edward would never be crowned. By the end of the month, and amidst a power struggle over the custody of the king’s person (in which the Woodvilles featured prominently) the 12-year-old king had been captured by his uncle, Richard of Gloucester, with his officials and attendants arrested or dismissed[ref]Richard’s motives remain uncertain, and much debated. At first, he may simply have been seeking to consolidate influence and control around the king, and to fulfil his position as Lord Protector during Edward’s minority. At some point, however, his plans changed, and as Charles Ross has written, ‘If Richard had not yet decided to take the throne for himself by the end of May, he was soon to do so’: Charles Ross, Richard III (Yale, 1999).[/ref]. A few weeks later, he was resident in the Tower of London, where his younger brother, Richard Duke of York (who had taken sanctuary at Westminster with his mother and sisters after Edward’s capture), would join him on 16 June.

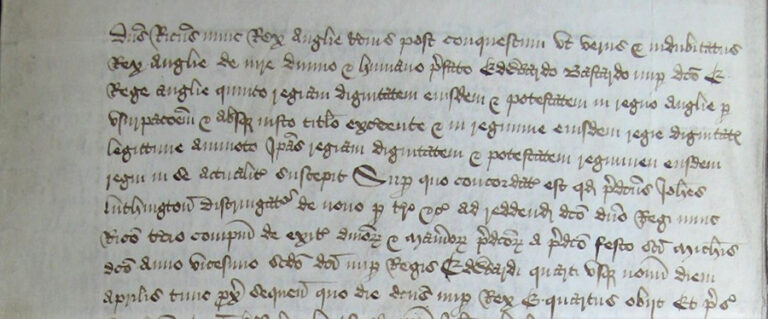

The date of Edward’s coronation was postponed on several occasions, but would never take place. On 22 June 1483, at Paul’s Cross in London, Richard III’s claim to the throne was set out. There has been much debate about the exact contents of this claim, but perhaps the most detailed and developed account features in the Titulus Regius. This alleged petition, presented by Richard in the January/February 1484 parliament he controlled, sought to legitimise his title and cast Edward IV’s reign as morally corrupt[ref]Other accounts of this early claim to the throne state that Edward IV himself was declared to have been a bastard, a rumour which had been circulated by Warwick and Clarence during the Readeption. In either case, Edward V would have been declared ineligible for the throne of England. It is entirely likely that both rumours and claims were circulated simultaneously.[/ref].

It claimed that Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville (who was also accused of sorcery and witchcraft) was not valid, because it had taken place in secret and without the assent of the lords, while Edward himself had been pre-contracted in marriage to another woman. The children of this marriage (including Edward V) were therefore bastards, and had no claim to the throne.

Whatever the exact content of Richard’s initial claim, the result was the same. On 25 and 26 June an assembly of lords temporal and spiritual (who had originally come together for Edward’s coronation), invited Richard to take the throne and he was crowned shortly afterwards on 6 July 1483.

Edward and his brother, the ‘Princes in the Tower’ were never seen again, with their fate a hotly debated subject ever since. Whether they were murdered (either by Richard’s orders or by Henry VII some years later), whether they died of natural causes in the Tower, or whether they escaped, we may never know what happened to these two boys, once the great hope for peace in England.

Born in a time of unrest and civil war, in sanctuary at Westminster, Edward V’s deposition and probable death in 1483 would plunge the country back into civil war. Ultimately, it would not be Edward who would end up on the throne, but his elder sister Elizabeth of York, who would marry Henry Tudor and unite the two sides, ending the Wars of the Roses for good.

Article ‘the birth (and death) of Edward V’. Note 4 at the end of this item says that ‘In either case, Edward V would have been declared illegible for the throne’. More likely that he would have been ‘ineligible’!

Thanks Victor – corrected now!