What do you think it is that links:

- Poisonous plots and rebellious Scots

- Guy Fawkes and Lady Jane Grey

- Regicides and Luddites?

All of these stories, and many more, can be found in the series of records known as the ‘Baga de Secretis’ – the ‘Bag of Secrets’ (The National Archives series KB 8). These are the trial records of some of the most important trials – most for treason – to take place between the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries, kept in a secret storage closet at Westminster.

In this blog I will examine how the Bag of Secrets came to exist, a secretive new repository accessible only by the leading royal judges, brought about in response to Tudor paranoia (and pretenders to the throne) at the end of the Wars of the Roses.

Not yet sensational

The first documents in the ‘Bag of Secrets’ series date from the end of the fifteenth century, but the term ‘baga de secretis’ is first known to have been used around 1344. It referred to the groups of indictments (formal charges brought against individuals in a particular court, the Court of King’s Bench) collected in each term of the legal year, or after specific commissions (called ‘Oyer and Terminer’, meaning ‘to hear and to determine’) had returned the findings of their investigations to the court.

These were not specifically sensitive files, only ‘secret’ in that they were only to be accessed by authorised staff of the royal law courts (see footnote 1). As such, the earliest Baga de Secretis was in fact little more than a series of term indictment files, which had become a regular series by 1385. Throughout the fifteenth century those files continued to be referred to as such in the King’s Bench Controlment rolls (KB 29), the court’s own records which traced the progression of cases held in the King’s Bench.

A secret repository

During the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII, the term ‘baga de secretis’ came to be applied not to the annual indictment files, but primarily to a few bags of considerable constitutional or political importance. These were now kept in a new repository, a special closet at Westminster (not now in existence, as far as we know), with access limited to three key holders: the chief justice of King’s Bench (informally known as the Lord Chief Justice), the Attorney General and the Master of the Crown Office.

The creation of the secret new repository was probably a reaction to the trial of Edward, earl of Warwick in 1499, as the evidence of the first two files in the series demonstrates.

Warwick‘s father, George, Duke of Clarence, had been attainted and executed for treason (allegedly drowned in a barrel of malmsey wine) by his elder brother Edward IV in 1478, after a tumultuous year following the death of his wife and youngest son. Clarence had run roughshod over the English legal system – rigging a jury to execute a (likely innocent) household servant he suspected of poisoning his family, and forcibly defending one of his retainers, who had been implicated in charges of treasonous necromancy against the king and executed.

As a consequence of Clarence’s attainder – the tainting of his bloodline that was associated with treason – his son Edward had been disinherited from any future claim to the throne of England, and his lands, possessions and titles were forfeited to the Crown. He was three years old at the time.

While he retained the title of earl of Warwick, in reality Edward’s childhood was spent in various forms of imprisonment or custody, kept out of the public eye, particularly after Henry VII’s usurpation of the throne. By that time he represented the best Yorkist claim to the throne (but only if his attainder were to be reversed).

A fear of traitors

As Henry himself had proven, an attainder could be secured or overturned posthumously – should the fortunes of war go in your favour. Faced by a series of uprisings in the 1480s and 90s led by pretenders to the throne (individuals claiming to be the missing Princes in the Tower), Warwick himself was framed as a traitor.

In 1499 he was put on trial for attempting to break out of the Tower of London. It was claimed that, alongside the pretender Perkin Warbeck, he planned to blow up all the gunpowder and steal valuable jewels from the treasury in the process.

Warwick and Warbeck were both executed as traitors, but a Tudor fear of Yorkist pretenders appears to have remained. In response to the trial, a new form of secret and secure storage would be created: a repository, taking on the old name Baga de Secretis.

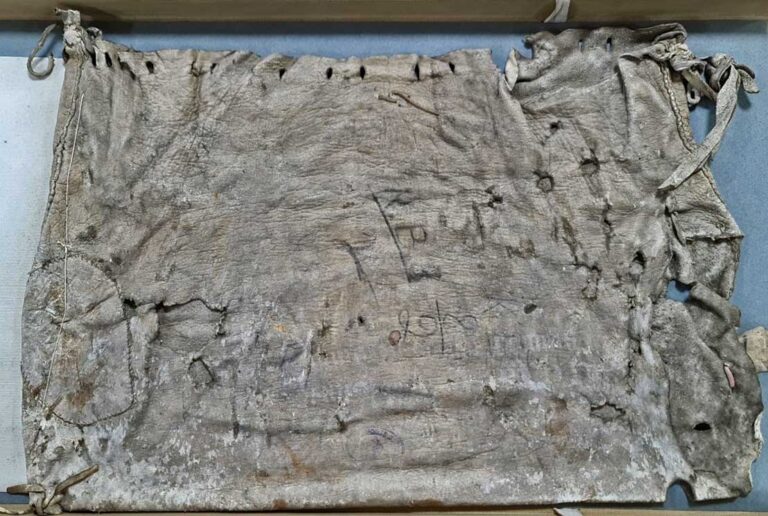

The records of Warwick’s trial were transferred to this new secret closet at Westminster, where the records were stored in an individual leather sack. They now form the second piece in the series KB 8, still with their original sack (KB 8/2, see footnote 2).

Given the sensitivity of the trial and potential Yorkist claims to the throne, however, the King’s Bench clerks appear to have gone back further into the court’s archives for any important precedents. As Warwick’s removal from the line of succession had been based solely on his father’s attainder, any legal proceedings connected to this attainder were also tucked away into the new secret repository.

While the exact circumstances which led to the bill of attainder brought against Clarence in 1478 remain difficult to unpick, two distinct sets of proceedings – the trial records of Clarence’s retainer Thomas Burdett, and the charges brought against Ankarett Twinho, the woman accused of poisoning Clarence’s wife and son in 1477 and executed – were sought out and placed in the new repository, along with the rest of the regular records from that legal term (see footnote 3). These now form the earliest records of the series and can be found in KB 8/1.

Finding its purpose

It is possible that the creation of a new secret repository for particularly sensitive records may have caused some confusion among the King’s Bench officials. In the year after Warwick’s trial, all of the indictments for that year were passed to the new secret closet, regardless of their political, legal, or constitutional importance, and are now found in KB 8/3. Few, if any, of the cases are of particular interest, and must have been sent there in error.

It was seemingly then decided that the new repository was to be reserved solely for cases of importance, with the court returning to its usual practice when processing the mass of every day criminal indictments it dealt with, rather than sending these to the secret closet. Each set of records was stored in an individual leather bag – in the same way Warwick’s records had been – with the contents of each bag written on the outside, and the bags filed away in the closet for safe-keeping under lock and key.

The Baga de Secretis was now firmly a repository for the records of some of the most important, sensational, and constitutional ‘state trials’. It would last as such for the next three centuries – a secret closet where the trial records of Anne Boleyn, Thomas More, the Gunpowder plotters, those plotting to place usurpers such as Mary Queen of Scots on the throne, and the regicides who had condemned the king himself of treason, could be kept safe from prying eyes.

Today, however, all of the records can be ordered and viewed by anyone with a valid reader’s ticket in the reading rooms – the Bag of Secrets, secret no longer.

Footnotes

- The idea probably developed from the bags used – from Edward I’s reign onwards – by coroners, with the rolls presented in a bag and sealed and the end of the eyre or circuit. Some bags are labelled with individual names, some with counties, and similar leather bags can be found throughout the records of the Exchequer.

- Following conservation work in the 1930s, the original bags can still be viewed with their corresponding trial records, although the trial records are no longer stored within them.

- The second half of KB 8/2, the records of the trial of Perkin Warbeck, were not necessarily stored in the secret closet initially. While they closely relate to Warwick’s trial, they were discovered in 1891 by Public Record Office staff, ‘found … among miscellaneous records packed away in large sacks and boxes in a dark basement’. They were then added to the Baga de Secretis series. (The Fifty-Third Annual Report of the Deputy Keeper of Public Records, p. 15)

Further reading

- Vernon Harcourt, ‘The Baga de Secretis’, The English Historical Review (July 1908)

You can find out more about the stories touched on in this blog in our exhibition Treason: People, Power & Plot, which runs until 6 April 2023, where you can view the following documents and many more:

- The 1352 Treason Act

- Trial records from the Baga de Secretis including Anne Boleyn, Thomas More, Guy Fawkes and the Ridolfi plot, as well as one of the original leather bags

- Richard III’s attainder after the Battle of Bosworth

You can find out more about Edward earl of Warwick and this plot in our recent podcast episode Treason: Betrayal and Deception, part of our On The Record Treason series.

You can also read more in our book, A History of Treason, available to purchase now from our online shop and all good booksellers.

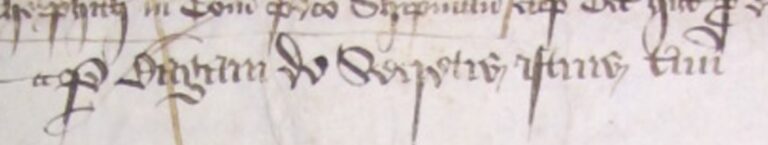

Thanks for this, very interesting. Do the T&S in the margin of the Earl of Warwick document actually stand for the subjunctive “Trahatur et Suspendatur”, i.e. “he is to be drawn and hanged” or something to indicate that he had been, e.g. “tractus et suspensus”? I thought he was beheaded?

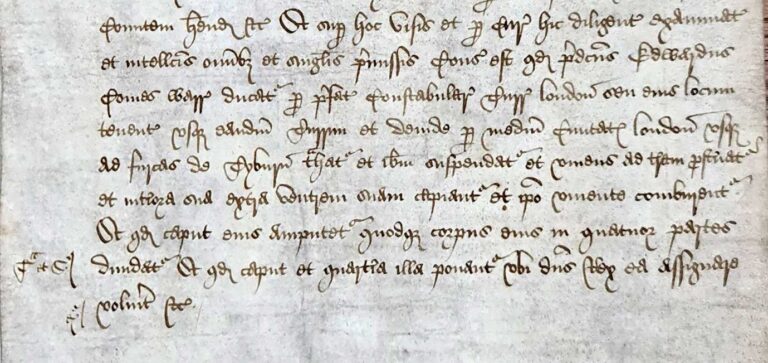

Thanks for pointing this out, the sentence indeed states that he was to be drawn and hanged (‘Trahatur’ and ‘Supendatur’ are given in the text itself – fifth line down in the image in the middle), rather than indicating that the sentence had already taken place. A few words had accidentally been left out. We’ve edited this now. Chronicle accounts state that his sentence was later commuted to beheading, but this is not mentioned in the records of the trial.

Would any of this explain, in part or as a whole, the phrase “To let the cat out of the bag”?

Thanks for this. A good question, but the answer is: not that I am aware of!

Was Warwick in fact executed as a traitor – despite his royal birth, which even the attainder couldn’t cancel, surely? I’m sorry I can’t read the Latin well enough to make out all the detail, but surely there would have been comment if he had actually been taken to Tyburn for execution?

Thanks for your comment. Chronicle accounts of Warwick’s execution do indeed state that his sentence was later commuted to execution by beheading at Tower Hill, rather than the full execution by drawing, hanging, disembowelling and quartering at Tyburn that the original sentence prescribed. This was often the case in executions of noblemen, but was not guaranteed, and was still the execution of a traitor. The original trial records referred to in this blog were not, however, amended to reflect any later commutation.

Fascinating!

This is so intriguing. I’m writing a YA novel about Elizabeth Tudor during the reign of her brother, King Edward VI. I would like to find out who were the Lord Chief Justice, the Attorney General and the Master of the Crown Office in 1547. So far, I’ve identified the first two (see below), but I’ve been unable to identify the Master of the Crown Office in that year. Does anyone know?

Sir Richard Lyster, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales from 9 Nov 1545 to 21 March 1552

Henry Bradshaw, Attorney General from 8 June 1545 – 21 May 1552