The Archivists’ Guide to Film is a blog series in which staff at The National Archives write about favourite films that have a connection to documents held in our collections. The films cover a wide range of topics and historical periods, from the Second World War to key moments in social history.

So settle in with your snack of choice and get ready to brush up on your film and history trivia knowledge. You’ll be ready when the pub quiz makes its return…

The third film in our blog series is ‘The Great Escape’ (1963) directed by John Sturges. Based on the biography The Great Escape (1950) by Australian ex-serviceman Paul Brickhill, the film depicts the true story of the Allied airmen who escaped from the German prisoner of war camp Stalag Luft III in Poland in March of 1944.

Since its release, the film has been both praised and criticised. The film is considered a classic for its great action, its ensemble cast, its top-notch humour and the escapism it offers. However, critics have brought attention to its many historical inaccuracies and its tendency to glamorise a tragedy. Despite some missteps, the film is noteworthy for its demonstration of the heroics and ingenuity of the prisoners. It includes many truthful details of the escape that are fascinating and surprising.

Stalag Luft III was a large prisoner of war camp containing thousands of men, most of whom were experienced escapers gathered together by the Germans so that they could be heavily guarded. In order to escape the camp, Allied prisoners planned the digging of three tunnels which they named Tom, Dick and Harry. Tom was discovered by guards during its excavation in 1943 and blown in, but work carried on with Dick and Harry and, ultimately, Harry was the one chosen for escape.

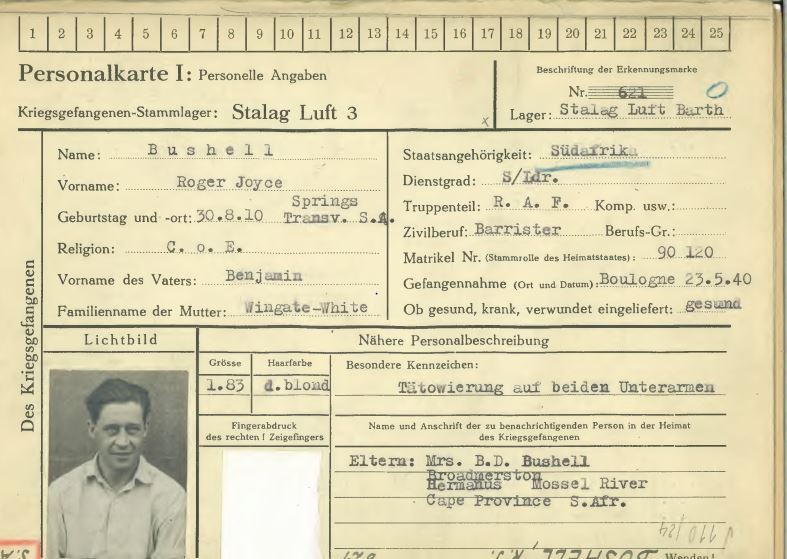

The film has two main characters: Bartlett (played by Richard Attenborough), a British officer who leads the escape planning, is based on RAF Squadron leader Roger Bushell, and Hilts (played by Steve McQueen), an American responsible for the majority of the action scenes in the film, including a chase involving a motorcycle and the Gestapo.

While the escape planning was a collaborative effort between many Allied prisoners, some of whom were American, all Americans in Stalag Luft III were transferred to the camp’s South compound in October 1943, and therefore were not involved in the escape months later.

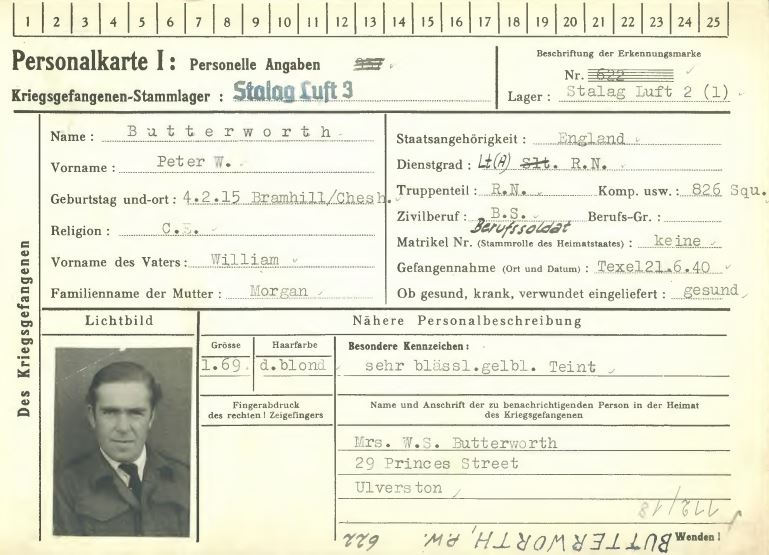

The WO 416 series (which is currently being catalogued by individual internee/prisoner of war with a timetable for completion indicated at series level under Arrangement at this link) consists of an estimated 190,000 records of individuals captured in German-occupied territory. One of the first records in the series is that of Peter Butterworth (WO 416/53/114). The actor, famous for his roles in the ‘Carry On’ films, had been captured in June 1940 when serving as a lieutenant in the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm, and had been sent to Stalag Luft III, helping prisoners immortalised in the film to escape.

Of the total number of men who tried to escape, only three completed a ‘home run’ – a term meaning they had escaped from inside a camp and made it all the way home. Out of 160 escaping officers, 76 men escaped before the tunnel was discovered by German guards. Sadly, 50 men were shot by the Gestapo on Hitler’s orders, and a total of 152 RAF personnel died in captivity during the war.

At the end of the war, General Major Westhoff provided a verbatim account of this shooting, which is available to view in full at The National Archives in the KV 2 series. Westhoff recalled that Fieldmarschall Keitel had stated in a conference immediately after the event that ‘…these escapes must stop. We must set an example. We shall take very severe measures. I can only tell you that the men who have escaped will be shot; probably the majority of them are dead already’. The order had come directly from Hitler and Himmler, despite the fact that attempting to escape was not a dishonourable offence, which was established in the Geneva Convention.

The film depicts many of the creative ways in which the prisoners worked together to plan their escape. Many men who spoke German fluently were elected for the escape, and they carried forged passes and wore modified British uniforms which they altered themselves. They also acquired some German uniforms through bribery and blackmail.

The ‘penguin method’ was used to disperse soil excavated from the tunnels outside of the huts. This involved filling bags with the soil which was then hidden inside clothing and released outside using a drawstring system. As in the film, there was much happening in the camp to distract from the covert work being done inside the huts. There was a camp theatre, where actors like Peter Butterworth entertained soldiers. Men gathered materials from around the camp for use, including bed boards and benches for building ladders and lining the tunnels, blankets and mattresses to muffle noises, and cutlery and cans to dig with.

In one particularly humorous scene in the film, one man jumps into the top bunk of his bed hoping for some relaxation only to crash to the ground as the bed boards have been removed. Many similar stories, retold by individuals who were successful in their escapes, were compiled as part of the Directorate of Military Operations and Intelligence, and are available to view at The National Archives as part of the WO 208 series. They record the ingenuity and often daring methods utilised, such as those seen in the film, by personnel as they made their bid for freedom.

This film is worth watching for many reasons. It has one of the most recognisable soundtracks in film history and the excellent script and acting celebrate the sprit, bravery and humour of the Allied forces. Perhaps the best part of watching is learning more about how these men used the resources available to them and worked collaboratively against all odds.

For more information about ‘The Great Escape’, take a look at the War On Film video, listen to Alan Bowgen’s podcast The Great Escape: you’ve seen the film, now hear the truth, and read more about our WO 416 record series in Roger Kershaw’s blog.

An excellent post – as expected and anticipated on this blog. Even in terms of war-themed films the subjects could be endless – The Dambusters, Sink the Bismarck, Operation Crossbow, Carve Her Name with Pride etc.

And then there’s the post-war The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and (stretching the point a little to encompass TV) Cathy Come Home.

I could go on but it’s not my blog!

Regardless of subjects chosen this is an accessible, informative and entertaining series. Please continue!

I had the chance to know Bobby Laumans, a Belgian pilot with 74 sqn and later 350 (BE) sqn. In 1942 he crashed into the sea after a dogfight and was picked up from his dinghy after 3 days floating between Belgium and England by the Germans. The rest of the war he spent in Stalag Luft III where he helped to make ‘The Great Escape’ reality. Unfortunately or as he sometimes whispered maybe luckily he was chosen to help digging the tunnels and was not on the list of the ones designated to escape. He was a very charming person who started a career as SABENA pilot in 1946 and died at the age of 93 in 2014.

In my fathers war log compiled while he was in Stalag Luft III there is a painting of a POW crashing through the bunk beds due to lack of bed boards…its entitled “ Ace bails again “

There is also a pen and ink drawing of the goon tower collapsing when they blew Tom up, I believe this drawing to be unique as no record was allowed to exist of this event.

Any mention of Bill Ash?

A great film to watch. One just needs to enjoy it for what it is and keep in mind its characters are mostly composites or inspired by real people or events. Bushell incidentally was born in South Africa. Interestingly his POW card above indicates this under his place of birth and nationality.

I’m an actor who worked with Cy Grant, a black Caribbean performer, who was a navigator and was shot down over the Netherlands, captured and taken to Stalag Luft 3, which made me wonder how many black Caribbeans from the 500 air crews ended up in that POW camp.

A great movie to watch. You just have to appreciate it for what it is and keep in mind that its characters are mainly composite or inspired by real people or events. Bushell was also born in South Africa. Interestingly, his POW card above indicates this under his place of birth and nationality.

From

https://www.freegpl.com

Many thanks for a very interesting read. On the Donald Pleasence character in the film – the camp forger – who lost his sight and was thereby shot during the escape . . .

In reality, there was more than one forger involved, along with escape maps, money and other paper items being delivered into camp hidden in the likes of games sets – behind the paper coverings of playing boards, etc. The story of MI9, which very secretly produced such items for helping prisoners escape, was given in an excellent presentation at the National Archives by Alan Bowgen, around 9-10 years ago. Those who returned safely to the UK would most likely have been interviewed by MI9 officers in the Great Central Hotel, Marylebone, London – now The Landmark Hotel.

The leading prisoner artist in this respect was Ley Kenyon who, prior to the escape, drew six pictures of the escape tunnel ‘Harry’ as a visual record, which were hidden in a home-made waterproof container in ‘Dick’. Although ‘Dick’ was flooded, a British officer who remained behind until the camp was overtaken by the Russians, successfully recovered the pictures and brought them home: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/greatescape/sketchbook.html

In practice, the escape number drawn by Ley Kenyon was so far down the list that the tunnel was discovered before he had a chance to escape and so he survived the executions. After the war he became a regular open-water diver and Jacques Cousteau’s European representative – for which he held a very early reel of 16mm film showing the beginnings of modern scuba diving. Ley Kenyon’s sister, June Barnett, gave me the film in 1993 to use for the benefit of the Historical Diving Society – in whose film archive the original print is now preserved.

Thank you for the blog entry.

As I understand the real successful escapees had some assistance and support from the outside, with respect to instructions for where to go. In particular the two Norwegians went to a specific location in the port of Stettin and made contact with the Swedish ship which took them out of Germany. This seems to have been pre-planned.

Do you hold any records, or do you have any suggestions pointers for information about this assistance?

This post contains the wording below:

… the film depicts the true story of the Allied airmen who escaped from the German prisoner of war camp Stalag Luft III…

I think it’s worth noting that the film is not as described in the quote.

It is however a work of fiction based on the true events.

None of the named characters existed, no American prisoners escaped (they had been moved elsewhere) and the men recaptured were not executed all at once as the film implies.

These may seem like trivial points but they are important if we are to look at the escape as more than a vehicle for Hollywood stars.

As we get further and further from the event of the Second World War and those that experienced it first-hand become fewer and fewer, and their memories less reliable facts matter.