The Archivists’ Guide to Film is a blog series in which staff at The National Archives write about favourite films that have a connection to documents held in our collections. The films cover a wide range of topics and historical periods, from the Second World War to key moments in social history.

The fourth film in our blog series is ‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’ (1957) directed by David Lean.

Correspondence between film companies and the War Office turns up in a number of files at The National Archives. Usually, the correspondence centres on requests for support from the War Office. Film-makers ask to use military vehicles or personnel, or they want an endorsement that the events in their film are realistic.

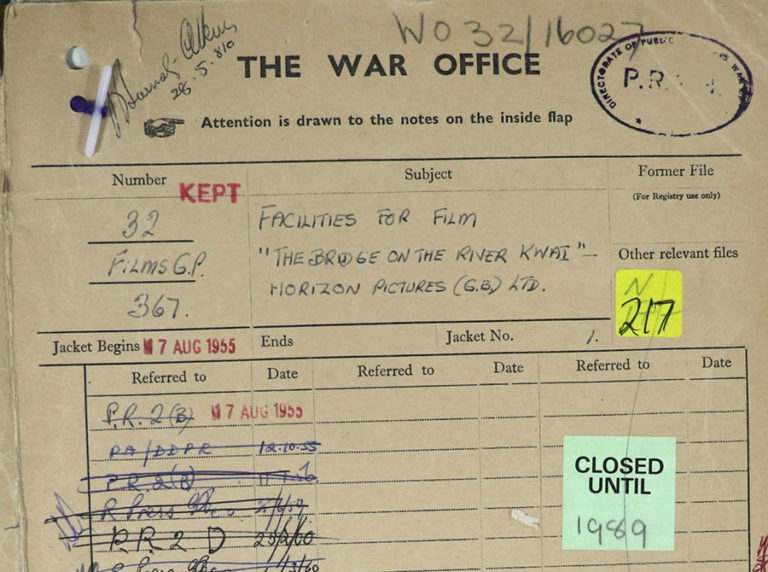

The items in a file relating to the film ‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’[ref]File reference is WO 32/16027[/ref] are more personal. They include a number of letters from Horizon Pictures (GB) Ltd, the Public Relations Department of the War Office, and the Chairman of the National Federation of Far Eastern Prisoners of War (FEPOW), Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival. These letters reveal the difficulty when fiction conflicts with a very personal reality.

A number of the people that appear in the correspondence had served in the Far East themselves. Some had been prisoners of war working on the ‘Railway of Death’ that the film’s plot is based on. Lieutenant-General Percival[ref]Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival CB, DSO and Bar, OBE, MC, OStJ, DL was General Officer Commanding (GOC) Malaya when, following the rapid advance of Japanese troops to Singapore, he surrendered on 15 February 1942. Churchill claimed the fall of Singapore was ‘the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history’ but military resources had been focused on the Middle East and the Soviet Union leaving Percival with insufficient resources[/ref] himself was a major figure who commanded the British Commonwealth forces operating in Malaya and Singapore. It was Percival who surrendered to the Japanese in February 1942 at the fall of Singapore, and the burden of responsibility for that situation must have weighed heavily.

The plot

The film centres on a British Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson, and Colonel Saito, the commandant of the Japanese prison camp in Burma (modern-day Myanmar) where Nicholson and his men are held. Saito insists that all the men, including the officers, should work on building a bridge to connect Bangkok and Rangoon. Nicholson refuses to allow his officers to perform manual labour (as per the Geneva Convention) and they are all detained in punishment huts. The other men under his command are made to work on the bridge, although they sabotage progress wherever they can.

Pressure on Saito to complete the bridge leads to a compromise and Nicholson decides that, if the men are going to be forced to work on the bridge, then they will design and build it properly. This will not only demonstrate their superior professionalism and skill to their captors, but also maintain the men’s morale as they will be able to take pride in their work. It’s this behaviour by Nicholson that is at the centre of all the correspondence, as we will see.

‘I do not think much of this story’

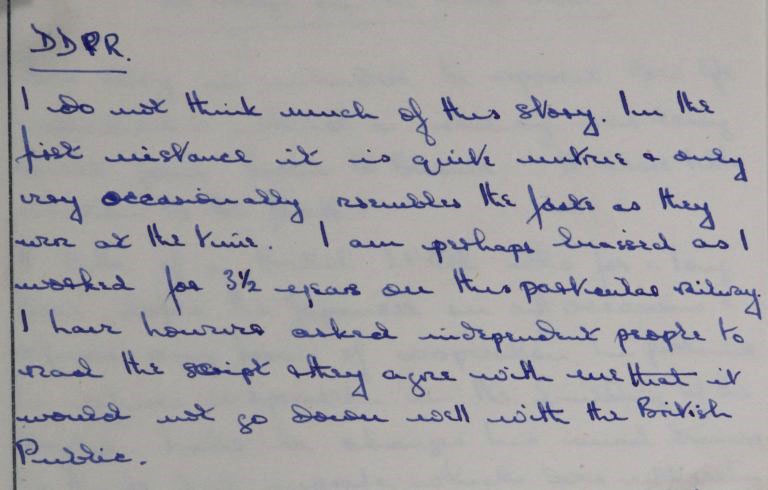

In April 1955 the War Office’s Public Relations Department was sent a preliminary script for the film. Various senior personnel made judgments about its merits and whether they should provide support to the film-makers. In September, Major A G Close wrote to Colonel L J Wood, Deputy Director of Public Relations, to say:

‘I do not think much of this story. In the first instance it is quite untrue and only very occasionally resembles the facts as they were at the time. I am perhaps biased as I worked for 3 and a half years on this particular railway. I have however asked independent people to read the script and they agree with me that it would not go down well with the British Public.’

Colonel Wood agreed, saying that it was difficult to believe that any British Commanding Officer would have acted in the way that the character of Nicholson does. The scriptwriter, Carl Foreman[ref]Carl Foreman was blacklisted by Hollywood after admitting membership of the American Communist party in his youth when he appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Foreman was not credited on the final film for this reason. Foreman also wrote the screenplay for the 1952 classic, ‘High Noon’.[/ref], tried to reassure the War Office. He wrote to say that he had been looking at the script with producer Sam Spiegel and would be making some changes. He told Major Close that ‘I think the changes in the script will remove whatever lingering doubts there have been in your mind on various aspects of it’.

In July the following year, 1956, Horizon Pictures (GB) Ltd contacted the War Office to ask for official approval which would clear the way for the RAF to assist with some parts of the film. The Assistant Director of Public Relations, Lieutenant-Colonel J H S Martin, replied with half-hearted consent:

‘As you know, on the basis of the script we hold, we are not entirely happy about this film story, which does contain certain inaccuracies and which does not, in our opinion, always authentically portray the behaviour and conduct of British Officers. Nevertheless, we have no intention of placing stumbling blocks in your way and we are prepared for you to assure the RAF that we have no objection to the proposed filming’.

A first-class lunch

With War Office authorisation in place, producer Sam Spiegel’s next move was to find a former prisoner-of-war who could advise him on ‘life in prison camp, dress and conduct of British prisoners’. He invited Colonel Wood to lunch to discuss this, but as Wood wasn’t free, he sent a Major Forbes in his place. The lunch appears to have been a lavish affair but it didn’t prevent Forbes from retaining concerns about official War Office endorsement. He wrote to Colonel Wood:

‘Many thanks for the lunch which, as you said would be first class, was! … I believe the film in its final form will not be as bad as it appears from the script. I do NOT think we should give official WO blessing but I do consider that it would be in our interest to have a well briefed RO [Retired Officer] who was actually a prisoner advising the film co.’

Whether any names were put forward by the War Office isn’t clear from the correspondence, but Spiegel did find a technical director in Major-General Lance Perowne, a former commander of the 17 Gurkha Division in Malaya.

Letter from Percival

Well into the following year, in April 1957, the War Office was contacted by Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, Chairman of the National Federation of Far Eastern Prisoners of War (FEPOW). He had heard that a film was being made, based on the original book by Pierre Boulle with which he appeared to be familiar. He wrote on behalf of the FEPOW Committee to express serious concerns that people who saw the film would think it was based on truth. He said:

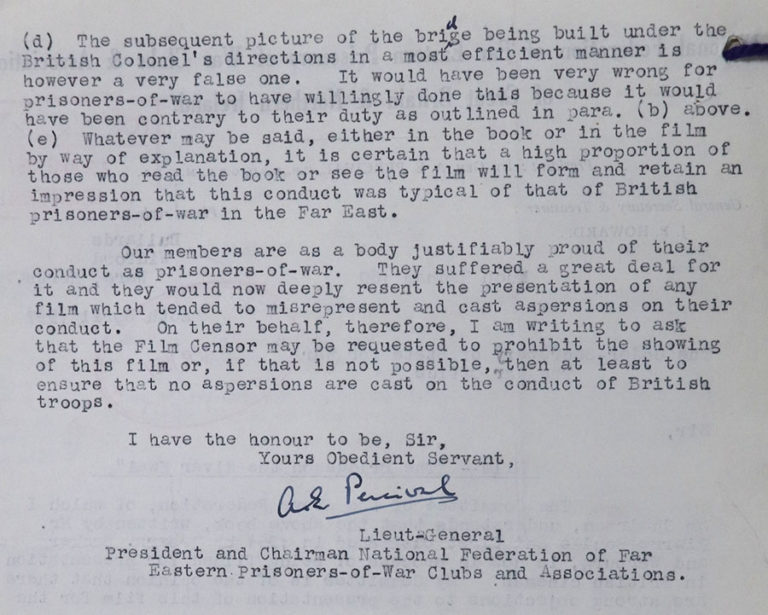

‘It is reasonable to expect that the public who see the film will think that the events which take place in the film are typical of what actually happened…our members are as a body justifiably proud of their conduct as prisoners-of-war. They suffered a great deal for it and they would now deeply resent the presentation of any film which tended to misrepresent and cast aspersions on their conduct.’

The War Office, obviously cognisant of Percival’s role in the fall of Singapore and all that followed, took his objections seriously. The Director of Public Relations, Major-General Arthur Charles Shortt[ref]Major-General Shortt CB OBE was previously Director of Military Intelligence 1949-1953[/ref] wrote to Percival explaining that they hadn’t given any assistance to the production of the film, other than to say that they didn’t object to it being made.

Spiegel defends his script

A few months later, Sam Spiegel gave a detailed and decidedly non-military defence of the script. He wrote to Colonel Wood saying:

‘…we have most earnestly tried to present a case in which officers and soldiers of various nationalities are caught in the inevitable tragedy which the military traditions of their respective nations impose on them in times of war. Each one has to resolve his problem in terms of his own conscience, his own beliefs and his own traditions. The irony of it is that, by following his own course, each one of them courts disaster and becomes the victim of his own integrity. Neither the British, nor the American, nor the Japanese participants in this tragedy caused by war behave in a way that could be considered typical of their national traditions. They all act as individuals. Yet none of them would reflect discredit on their national prestige.’

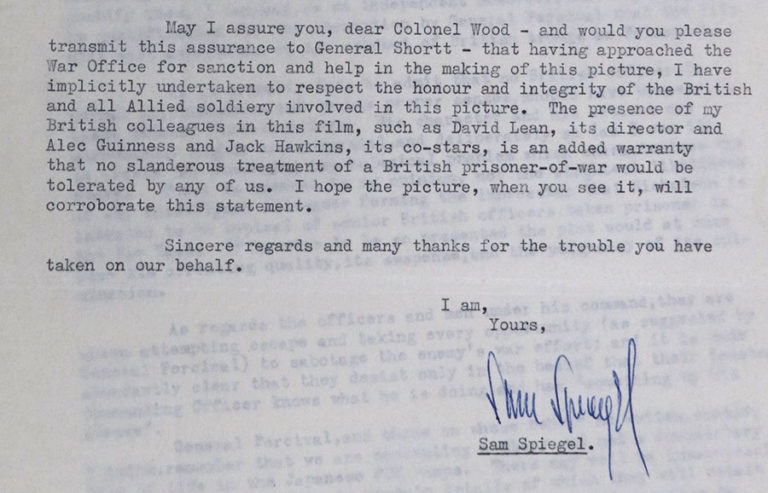

Spiegel stressed that the involvement of the British director, David Lean, and respected actors, Alec Guinness and Jack Hawkins, provided additional security that ‘no slanderous treatment of a British prisoner-of-war would be tolerated’. He also enclosed comments from his technical director, Perowne, who came down firmly on the side of the film producers.

Perowne accepted that no British officer ‘in normal circumstances and in his proper senses’ would have behaved in the way that Nicholson did, but he didn’t accept that audiences would confuse the fiction with reality. He also pointed out that the men under Nicholson’s command were seen sabotaging the bridge-building and attempting to escape. They only changed their behaviour on the orders of the Commanding Officer, who they believed must have had ‘something up his sleeve’.

Major-General Shortt was reassured and wrote to Percival to say:

‘As General Perowne points out the film is intended to present a “story” and not a documentary film of life in the Japanese POW camps. I do think we have to allow some latitude when we criticise film companies, who in nearly all cases, are out to present the Services in as favourable a light as possible.’

However, Percival remained unconvinced and took the matter to a meeting of FEPOW’s Executive Council. The Council passed a resolution ‘deploring’ the story on the grounds that ‘the incidents portrayed are directly contrary to actual fact’.

Reaching a compromise

Keen to find a compromise somewhere, Colonel Wood wrote to Shortt, his boss, with a suggestion. He wondered if Sam Spiegel might agree to a disclaimer at the opening and closing of the film, making it clear the events were fictional and that there was no implication of collusion by British officers or other ranks. Percival and Shortt both took this idea up and each sent a draft disclaimer to Spiegel. Percival appeared optimistic that this compromise would protect the reputation of his members, and following his attendance at a preview of the finished film, he wrote to Shortt saying:

‘I hope you have succeeded in getting Spiegel to agree a reasonable wording for the preliminary statement, and also to get the Colonel’s actions at the end brought out more clearly. Thank you for giving me the chance of seeing the preview. We certainly lived in the “film world” that day, didn’t we?!’

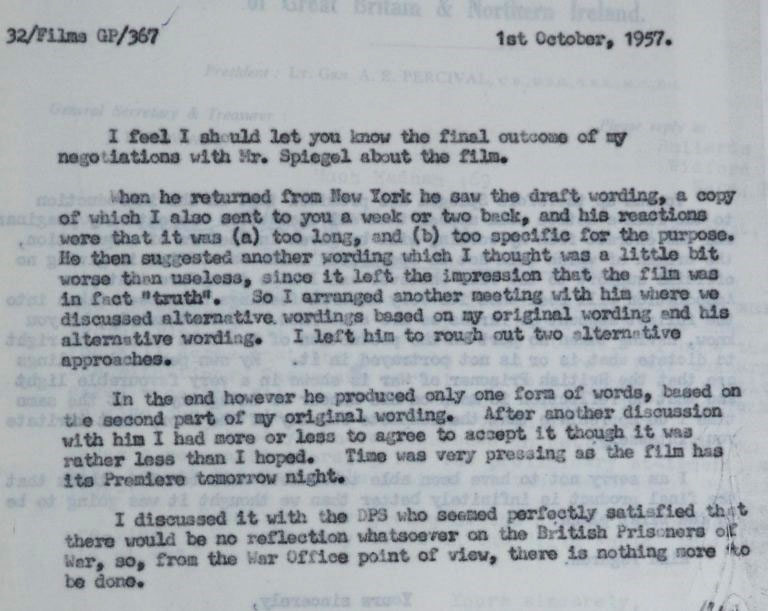

But Percival’s optimism seems to have been misplaced. Spiegel didn’t accept the suggested wording for a disclaimer, saying it was too long and too specific. Spiegel and Shortt met and tried to reach an agreement, but time was against them with the film’s UK premiere being the following evening. Eventually, Spiegel’s choice of wording was reluctantly accepted by Shortt, who could see he was not going to make further progress as he had no leverage. The War Office had not been involved in the production of the film and so ultimately had no right to dictate what should be shown.

FEPOW members angered

Once the film was released in the UK on 2 October 1957, it was clear that the disclaimer hadn’t been shown in the way the War Office and Percival had expected. Percival wrote to Shortt saying that the wording had appeared at some of the screenings in London but hadn’t appeared at all in other areas of the country. He added that members of FEPOW who had worked on the railway were ‘without exception very angry at the misrepresentation of their actions’.

In an effort to reclaim the reputation of his members, Percival wrote a letter to the press. He said that it had been the duty of the former prisoners to do the maximum damage to the Japanese war effort and that they did so ‘magnificently in the face of a ruthless enemy’. Many had suffered and died in the course of their sabotage efforts, and the members of FEPOW deeply resented the way the film had used their experience in a way that brought dishonour to them. Percival’s letter was printed in The Daily Telegraph, which seems to have cheered him as he wrote to Shortt saying, ‘I am now getting quite a fan mail as a result of it!’

The film didn’t provoke universal criticism from the military. The War Office file includes a copy of a letter written to Lance Perowne by Field Marshal Gerald Templer[ref]Field Marshal Sir Gerald Walter Robert Templer, KG, GCB, GCMG, KBW, DSO, was a former Director of Military Intelligence and High Commissioner of Malaya[/ref], proclaiming that having just seen the film, he thought it was ‘without any doubt at all, the best film I have ever seen in my life’.

Conclusions?

So what should we make of these events? Boulle’s book tells a story of individual struggles that related to the pressures of the recent war, while nevertheless being fictional. But by setting the story in a place and time that had been the very real scene of such suffering, it was inevitable that those involved in the events would feel it was about them personally. Had the story remained a book it would have been easier to ignore, but by putting it into cinemas and showing it to a worldwide audience, the reaction of many who had served in the Far East was surely a foregone conclusion.

I agree with your conclusion. When “A Bridge Too Far” (DEFE 68/85, 86,

DEFE 24/1248) was to be released the Ministry of Defence military advisers commented that one event in the film didn’t happen and one that did was not in the film. The same uproar could be said of the film “Titanic” when it was suggested that one of the officers (Murdoch) threatened to shoot passengers.

I had a cousin, now deceased, who was in Burma with the British Army. He survived the war and returned to England, later becoming very involved with the Burma Star Organisation. While he was not captured or subject to the atrocities of imprisonment, he spoke very harshly of the film. At the time of it’s release, I was attending University having just left the RAF and had become friends with an older student who himself had served in Burma in 1943-44. We saw the film together, and while we both admired the actors, I had no context for the “story” other than my own understanding of POW responsibility which denied what I had watched. He, meanwhile, was outraged at the content.