This blog post contains a ‘spoiler alert’ for those who haven’t yet seen the film.

Some of you may have had the opportunity to see the recently released film, ‘The Duke’. This highly entertaining comedy drama, starring Jim Broadbent and Helen Mirren, is based on the amazing true story of the theft of Goya’s painting of the Duke of Wellington from The National Gallery in 1961. The National Archives holds the original documents which tell this incredible story. In this blog post I’m going to highlight some of these.

It took four years for the painting to be recovered, and the man who was tried for this crime was a 61-year-old pensioner from Newcastle named Kempton Bunton. He was self-taught, with aspirations as a writer, and had a burning sense of social justice. Bunton had engaged in a long campaign for pensioners and war widows to receive free television licences. He had served a day in prison for refusing to pay a fine for operating his TV set without a licence.

In 1961 the British Government purchased Francisco Goya’s portrait of The Duke of Wellington (1812) for the nation at the cost of £140,000. It was put on display in the main entrance lobby of The National Gallery on 2 August. Twenty days later, on 22 August at about 09:30, it was reported to the police that the portrait was missing; it was then established that the portrait had been stolen the previous day, some time after 16:00.

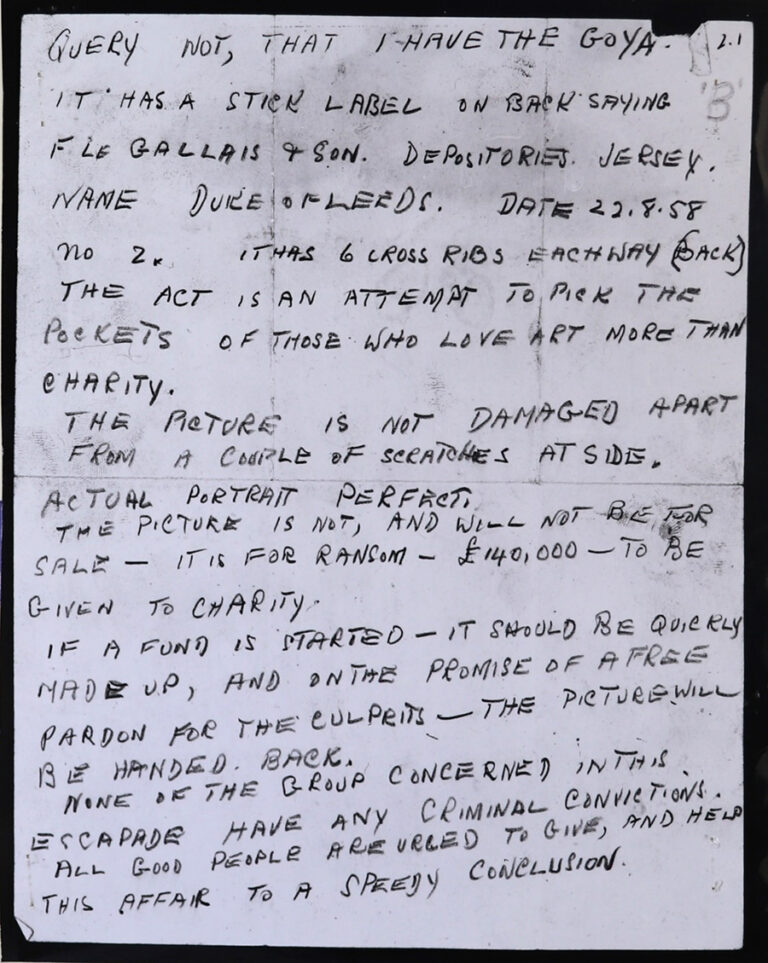

Ransom notes begin

The next significant development was a handwritten letter from a mystery person (later confirmed as Bunton) which used block capitals, sent to the news agency Reuters and postmarked 30 August 1961.

The ransom of £140,000 was the same amount that the Government had paid to secure the portrait for the nation. This request was declined and the case rolled on.

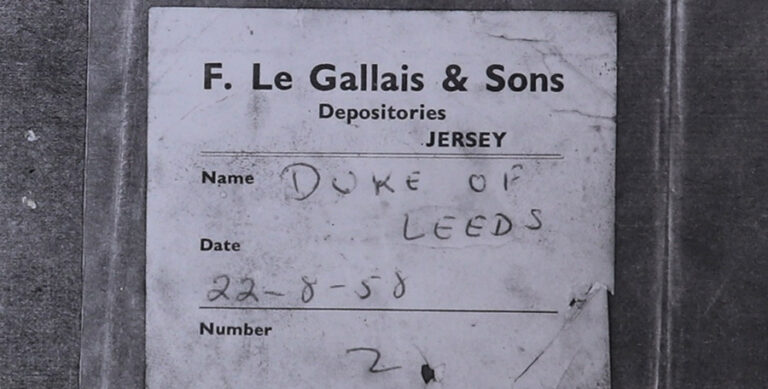

The next significant development was the receipt of proof that the mystery thief had the portrait – the sticky label of F. Le Gallais & Sons which had been fixed to the back of the portrait enclosed with a letter postmarked 03/07/62 addressed to the Exchange Telegraph, a company which transmitted news to subscribers.

Then Lord Robbins, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of The National Gallery, and Lord Rothermere, owner of the Daily Mail, received letters bearing on this matter (postmarked 20 May 1963). The message for Lord Robbins read: ‘I have the missing painting of the Duke of Wellington – you may have it back at £5,000 – this can be arranged provided that you work quietly … it is suggested that Lord Rothermere is the intermediary’. As with several of the numbered ‘Coms’ (or communications) which were to follow, there was a set of detailed instructions for paying the ransom and how the painting would be returned – the level of detail indicated a high level of ingenuity.

Recovery of ‘The Duke’

The matter remained unresolved, and time passed by. In March 1965, Bunton wrote to the Daily Mirror and demanded £30,000 for the return of the painting, a sum which was to be raised by a public exhibition of it. He even suggested that a committee could oversee the direction of the funds raised, which were to be directed to charity. Bunton demanded that a message be placed in the newspaper’s personal column which would effectively indicate approval for the plan. If his conditions were met, he told the Mirror, ‘you will receive a letter informing you to pick up the Goya’. The Daily Mirror did place a confirmatory message in the paper and Bunton wrote again; this time he enclosed a receipt for the left-luggage office at Birmingham New Street Station. The newspaper did not comply with its part in the deal, and alerted the police who used the receipt to retrieve the stolen portrait (very carefully wrapped and packaged) at that location.

However, the suspect remained elusive until (in July 1965) Bunton walked into Scotland Yard and confessed to the crime. In a statement, he declared himself ‘sick and tired of the whole affair’. He also stated ‘my effort has been honest to goodness skulduggery – but evil – no’ (see footnote 1). He gave a detailed and accurate description of the packaging that surrounded the retrieved painting, and his handwriting convinced the police that they were dealing with the originator of the ransom notes. Bunton gave a statement in which he admitted taking the portrait from The National Gallery in 1961. He explained that he had kept the painting in a cupboard in a bedroom at his home in Newcastle.

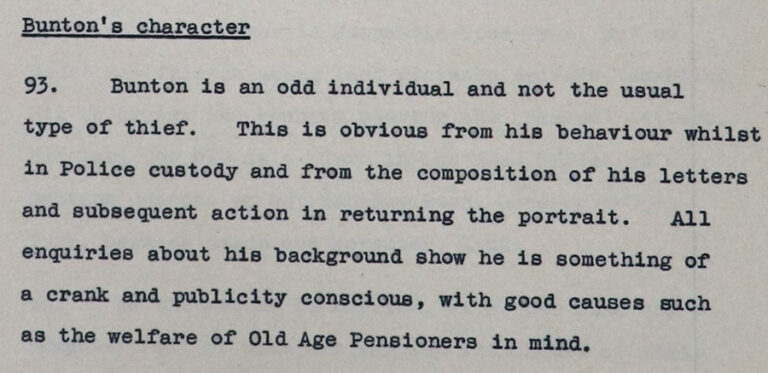

The authorities clearly found Bunton to be an unusual type of thief, as shown in a Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) report written before his trial.

In the trial that followed, it was said that, on 21 August 1961, when the gallery was closed to the public, Bunton had entered a toilet in The National Gallery through an open window and then gone in to the gallery. He had then removed the portrait from the display and escaped via the same window.

Bunton stated that ‘I had no intention of keeping the painting or depriving the nation permanently of it’. His defence team, led by Jeremy Hutchinson QC, exploited a legal loophole by arguing successfully that Bunton had never wanted to keep the painting, which meant he could not be convicted of stealing it. He was not found guilty of the theft of the painting itself, but of the frame, which was never recovered, and was sentenced to three months in prison.

Spoiler alert: There was a further twist to the story: the person who actually carried out the heist was Bunton’s son John – he confessed to it in 1969.

The proposal for a film originated from Chris Bunton, Kempton’s grandson. In a recent interview, referring to his grandfather, he acknowledged his faults but also spoke about his good intentions and how he ultimately wanted to do the best thing – that he was driven by a need to protect his family (footnote 2).

I must just add that the theft was even referred to in the first ever James Bond film, ‘Dr No’, in which the painting (or rather, a replica of the painting) is observed by Bond in the villain’s secret hideaway. This indicates the grip that the story had on the public imagination in the early 1960s.

Footnotes

- Statement by Kempton Bunton, Exhibit No. 29. Catalogue ref: CRIM 1/4422

- Is ‘The Duke’ based on a true story? Kempton Bunton’s grandson explains. Radio Times, 23 February 2022

He wasn’t a crank, he just thought the money paid for the painting would be better spent on pensioners. I agree.

it’s a pity the government doesn’t think like that too.

The film gives a slightly different story around the returning of the painting, and the inclusion of the clip from the Bond film is very amusing . Really good real life story.

EXCELLENT STORY OF A PERSON WITH TRUE FEELINGS FOR PEOPLE WORSE OF THAN HIM. TO MAKE THERE LIVES BETTER. NOT FOR PERSONAL GAIN.

A great film as only the British can do. Excellent characters played by the actors.

A quietly lovely film. Fascinating man. Isnt it sad that we value tbings over people. Through red tape, rules and regulations- thought up by governments and administrators – restrictions are put upon the most vulnerable and poorest in society. A underated film of our times and a man of courage and honest values.

Really loved this movie 🎬 the era was perfectly captured and the acting was wonderful …

I thought Kempton was a wonderfully kind & empathetic eccentric man that the world could use more of 🙏🤣😊♥️

A lovely film, well acted, which demonstrates that truth can in many instances be stranger than fiction. What an interesting guy Mr. Bunton must have been.

A charming film accurately capturing post War Britain of the early 60s. Jim Broadbent was exceptional in the role as Kempton Bunton. A man who was willing to go to prison rather than abandon his principles. The British do these films so well………..similar in it’s charm to Brassed Off, Local Hero, The Full Monty and many more.

Great story about a lovely man (reminded me of my grandad)

Got the era just right! Acting was spot on too. We need more films like this and more people like Kempton!

Really amusing and heartwarming movie. Such a shame more wasn’t made of kemptons fatherly instinct to heroically take the wrap for his son, which could and should have been the main thrust of the movie.

Good film,pity about the bad accents