This is the second in a series of blogs charting the progress of the Royal Navy Captains’ letters project. This project is being undertaken by a fantastic group of volunteers working to catalogue 564 boxes of Royal Navy Captains’ letters of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815), making them keyword and date searchable on The National Archives’ catalogue, Discovery.

In an earlier blog, I reported the completion of this work regarding Captains whose surnames begin with the letter ‘A’ for the document references, ADM 1/1448-1456. I am pleased to report the completion of the work for surnames ‘B’ and ‘C’ in the boxes ADM 1/1508-1561 (B) and ADM 1/1618-1669 (C) amounting to 24,939 letters and 7,921 enclosures. In this blog, I’ll go through some of the information and stories we’ve recently found. In it I make reference to letters which refer to some naval practices of the time that are not appropriate today, but that reflect the period.

William Bligh

Among these documents can be found 215 letters by William Bligh (1754–1817), who is perhaps best remembered as the commanding officer during the infamous mutiny on HMS Bounty in 1789. However, during his career Bligh served with and witnessed the killing on 14 February 1779 of the famous explorer James Cook by Hawaiian natives, was present at the Battle of Dogger Bank (5 August 1781) and served at the relief of Gibraltar in 1782.

During 1791–1793, when in command of HMS Providence, he sailed to the Society Islands, in the South Pacific Ocean, mainly to take breadfruit plants to West Indian colonies. He became embroiled in further mutinies on HMS Defiance in October 1795 and the Nore Mutiny of October 1796. He then was present at the Battle of Copenhagen (2 April 1801), in command of HMS Glatton. As Captain of HMS Warrior in 1805, following a court martial, Bligh was reprimanded for his tyrannous behaviour and language to a fellow officer.

In 1806, Bligh was appointed Governor of New South Wales but was deposed by a coup d’etat, the so-called Rum Rebellion, conducted by the New South Wales Corps unhappy with Bligh’s conduct, reforms and attempts to prevent the illegal trafficking of goods. Bligh eventually reached the rank of Vice Admiral in 1814 and died aged 63 in London.

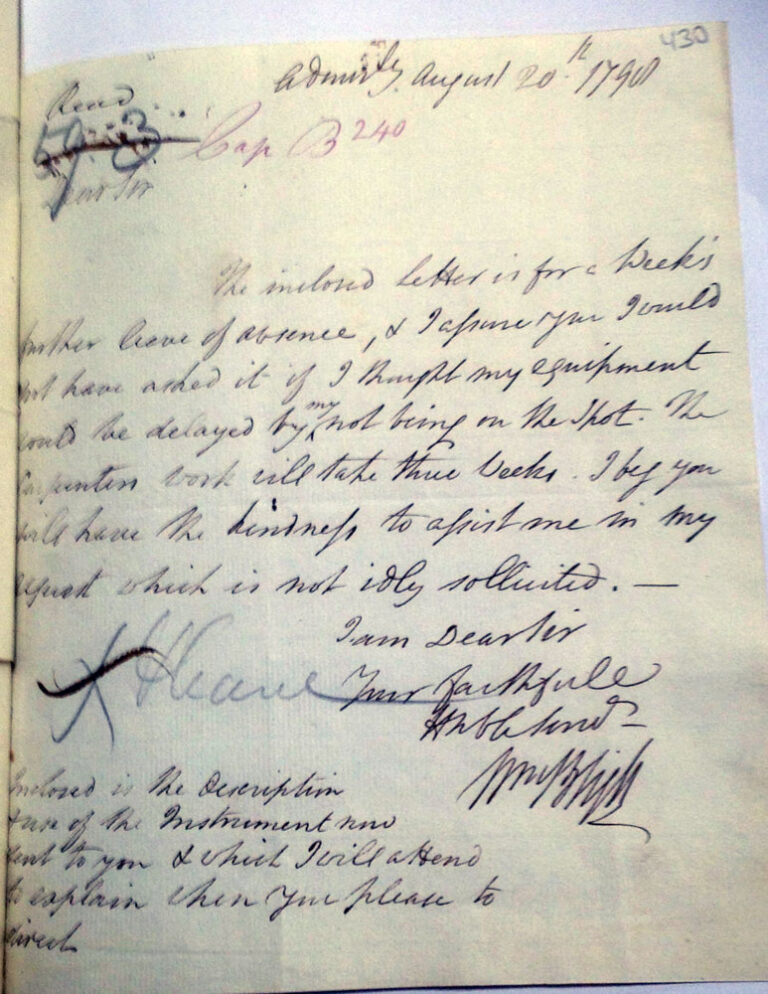

Not only a skilful seaman and hydrographer, Bligh was also an inventor. In an enclosure to a letter (ADM 1/1518/253 folios 430-433) Bligh wrote on 20 August 1798, he describes an instrument he invented ‘to regulate naval evolutions and for the readily taking bearings of land or ships when sudden emergency will not allow of time to use a compass for that purpose’. Bligh outlines how the instrument is made, its potential uses and the advantages it would bring to the service over expensive Azimuth’s compasses used at the time.

Recalling events at sea

Another letter (ADM 1/1512/37 folio 44) dated 28 September 1796 by Captain Alexander John Ball recalls an event where eight Black men on board HMS Argonaut, employed in the West Indies as a boat’s crew, had to work on a dangerously hot day in watering the ship while the rest of the crew sheltered. Ball stated their work ‘to be of infinite consequence, as it saved the remainder of my ship’s company from that exposure which has often proved very fatal’.

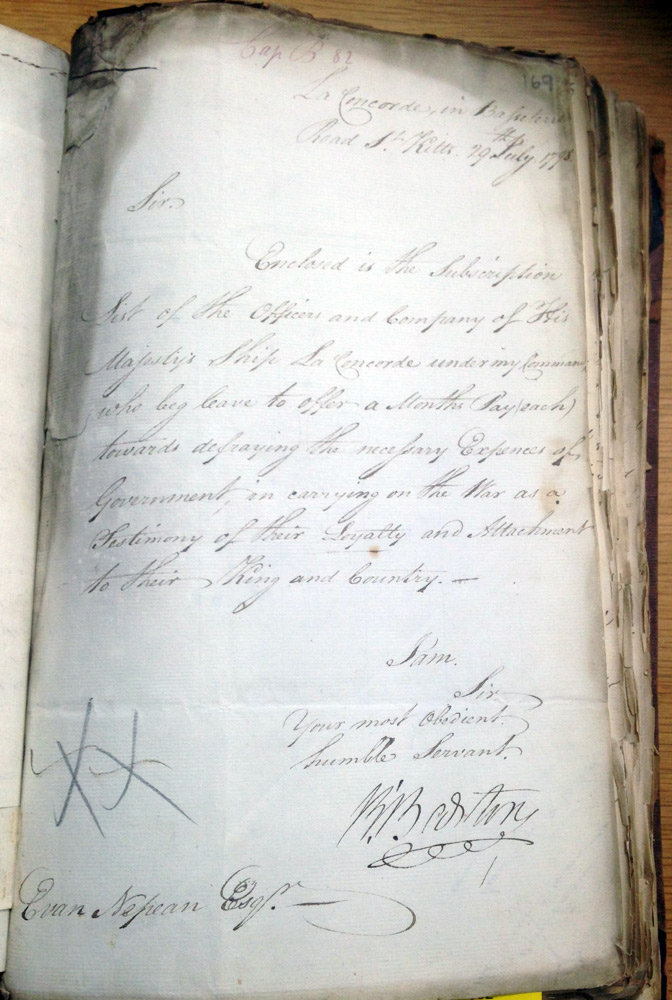

A further letter (ADM 1/1518/86 folios 169-171) dated 29 July 1798 by Captain Robert Barton of HMS Concorde in the Basseterre Roads, St Kitts, proudly alludes to a subscription list of his crew who ‘offer a month’s pay each towards defraying the necessary expenses of Government in carrying on the war as a testimony of their loyalty and attachment to their King and Country’.

Correspondence (ADM 1/1518/114 folios 223-225) dated 25 May 1798 from HMS Medusa at Spithead by Captain Alexander Becher contains details of French prisoners of war attempts to escape. Becher describes how Francis Uberry, a native of Dunkirk, managed to pass on to 30 other French prisoners kept in the ship’s main hold a ‘tinder box which it appeared was to procure a light for that purpose’. Becher reports Uberry’s justification for his actions as being ‘hard to be kept in a service against his country and inclination and that he would rather go to prison than remain in it’.

Another letter (ADM 1/1520/31 folios 53-54) dated 15 January 1798, from HMS Providence at Macau in China by Captain William Robert Broughton, reports his voyage of discovery findings concerning the Kurile Islands and Tartary coast, which he claimed ‘will serve to clear up all the fabulous accounts relating to these parts which has long engaged the attention of the world, from the various accounts given by the Dutch and Russian navigators’. Broughton adds that the ‘unfortunate shipwreck of HMS Providence prevented his survey to be undertaken ‘in a more extreme, complete manner’.

Thomas Cochrane

This project has also uncovered 83 letters written by Thomas Cochrane (1775–1860), one of the most flamboyant but controversial naval officers who served in the Napoleonic Wars and widely recognised as the real-life inspiration for Patrick O’Brian’s, series of books about possibly the most famous fictional naval Captain, Jack Aubrey, portrayed by Russell Crowe in Master and Commander (2003).

From March 1800 to July 1801 in command of the 14-gun HMS Speedy, Cochrane captured 50 ships, including the much larger 32-gun Spanish ship, El Gamo, double the amount of HMS Speedy’s firepower and six times further the number of men. Cochrane made a fortune in prize money, while being a major thorn in the French side, leading to Napoleon branding Cochrane as the ‘Sea Wolf’.

In April 1809, Cochrane led an outrageous and dangerous attack on French ships stationed in the Basque Roads off Rochefort which culminated in the loss of five French ships and much damage to the French Brest fleet.

Cochrane’s difficult character often brought him into conflict with powerful figures, His career both as a Member of Parliament and as a Royal Naval Officer was to end in ignominy as he was found to be guilty of fraud in the Great Stock Exchange trial of 1814. With little opportunity in both political and Royal Navy spheres, Cochrane was to serve with distinction between 1817 to 1827 in the foreign navies of Chile, Brazil and Greece in these countries’ efforts to gain independence. In 1832 he was readmitted to the Royal Navy reaching the rank of Admiral and served as Commander in Chief of the West Indies and America station until 1851.

An example of a different ‘capture’ by Thomas Cochrane accompanies a letter (ADM 1/1651/41 folios 90-91) he wrote from HMS Imperieuse at Gibraltar Bay on 17 October 1808. This was a French Semaphore Signal printed book taken from the Vigie de Bandan near the River Rhone, which he gave to Admiral Edward Thornbrough commanding Naval forces at Toulon. Cochrane states ‘how much importance these signals are to the safety of the French ships of war and to the protection of their convoys’ He added that he thought that these signals ‘appear more simple and clearer than the signals now used on our coast made with flags and balls on different staffs’.

Discovering rare details

A rare example of a list of gunner’s stores accompanies a letter (ADM 1/1622/41 folio 190) dated 3 December 1797 by Captain Henry Carew of HMS Swan at Sheerness. The list was produced because of a survey, dated 13 July 1797, of HMS Swan ordered by Admiral Adam Duncan of the remaining stores of the Gunner, William Chapman, who had lost his books in consequence of a mutiny. This list not only reveals details of the armaments of the ship but also the vast amounts of shot and other equipment that Gunners were tasked to manage.

In one letter, in support of his claim to receive a medal given by His Majesty to the Captains involved in the Battle of the Nile (1 August 1798), Robert Cuthbert, the First Lieutenant of HMS Majestic, recounts how the ship’s Captain, George Blagden Westcott was killed ‘within a few minutes after the commencement of the action’ and that HMS Majestic ‘was continued to be fought by me as First Lieutenant without interruption until half past three on the morning of the Second with an interval of only ten minutes, which was occasioned by the Le Orient blowing up at ten o’clock on the night of the first after which time I beg leave to observe that none other of His Majesty’s Ships were engaged except the Majestic and Alexander who very gallantly came down to our assistance until five o clock on the morning of the second when we again with the assistance of the Theseus and Leander commenced our fire on the retreating ships of the enemy’.

Cuthbert added (ADM 1/1627/217 folios 498-501) that in consequence of his gallant actions, ‘Admiral now Lord Nelson sent for me at eight o’clock in the morning of the second and gave me an order to act as Commander of the Majestic, a copy of which I have the honour to enclose’. On the British side during this Battle, HMS Majestic suffered the highest casualty rates, with 50 killed and 143 wounded.

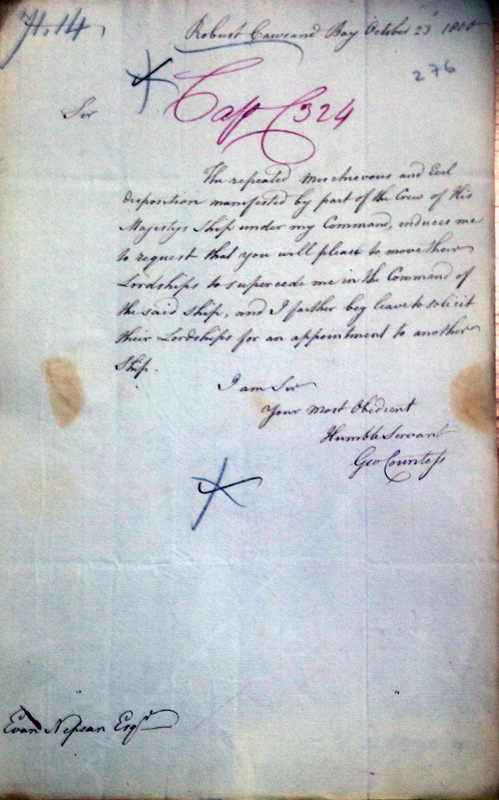

An unusual occurrence is evidenced in a letter (ADM 1/1629/107 folio 276) dated 23 October 1800 by Captain George Countess of HMS Robust at Cawsand Bay, who asks to be removed from his command owing to ‘the repeated mischievous and evil disposition manifested towards him by part of the crew.

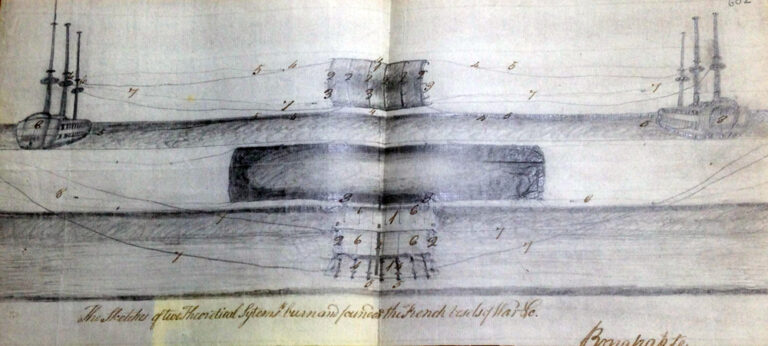

Another highlight is a drawing of an invention by Israel Coulson, Gunner of HMS Ulysses, enclosed with a letter (ADM 1/1639/229 folios 599-600) by Edward Henry Columbine, dated 13 November 1813 with ‘which it is hoped that the French flotilla at Boulogne would be greatly annoyed’. Along with the letter is a description of Coulson’s invention together with sketches of two theoretical systems to burn and founder enemy ships.

Are there any letters from captains about the efforts to halt the slave trade? Either off the West coast of Africa or the East.

There is every possibility that there may be such material. Given that the material is or will be keyword searchable, I’d suggest, keep tabs on project progress and search Discovery for relevant Captain’s names, locations and key words such as ‘slaves’ for related content, see such a search here.

A superb source of original, unquestionable first-hand historical documentation. To have this made available and searchable on-line is a major advance for researchers at all levels.

this is an interesting project, can’t wait for the letter G to be completed as it may have some records that I am interested in!

To trace letters from the captains pursuing slavers, I would recommend identifying the commodores of the West Africa Squadron, for example Charles Bullen (1824-7) and his successor Francis Collier (1827-1830). They were the main correspondents with the Admiralty and I found their letters (for example Bullen in ADM 1/1571 and Collier in ADM 1/1682) invaluable in a recent work on the subject.